How to Keep Social Security Secure

This article appears in the Spring 2018 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.

For the last 35 years, official government projections have reported that Social Security will be unable to pay some scheduled benefits sometime in the middle third of this century. For almost as long, the Congressional Budget Office has annually warned that the overall federal budget is on an unsustainable trajectory. Conservatives, some of whom still yearn to roll back the New Deal and Great Society, point to these projections as support for their claim that we can no longer afford Social Security, Medicare, and other so-called “entitlements.” Their declared strategy involves sowing doubts about the sustainability of these programs and creating a coalition to scale back or replace them.

So far, this campaign has enjoyed little legislative success, but the talk of crisis has made many people very nervous. Roughly two-thirds of the American public tell pollsters that Social Security is already in crisis or faces major problems. Smaller majorities say that they don’t expect to receive some or all of the benefits they’re due.

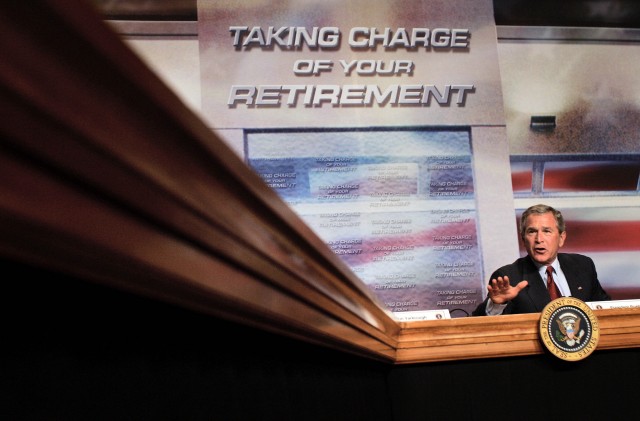

Nervousness has not eroded Social Security’s popularity. Solid majorities of liberals, conservatives, and independents alike say that Social Security is important and that they are willing to pay more in taxes to sustain it. The last major assault on the program, George W. Bush’s 2005 proposal to replace Social Security by diverting revenues into private accounts, turned into a political train wreck when members of the president’s own party shunned his plan.

The chief, indeed the only, argument for scaling back Social Security is that current Social Security taxes plus accumulated reserves are insufficient to pay all scheduled benefits beyond 2034, if current projections turn out to be exactly correct—or a few years earlier or later, if they are a bit off. In 2018, Social Security will channel more than $1 trillion in pension benefits to more than 62 million beneficiaries; by 2035, 88.4 million beneficiaries are projected to have earned entitlement to $1.672 trillion in benefits (in 2017 dollars). Revenues in 2034 are now expected to cover just three-quarters of scheduled benefits. If Congress makes no changes in the program, benefits will fall automatically by approximately one-fourth. To avoid benefit cuts altogether at that point, Congress would have to raise taxes earmarked for Social Security by approximately one-third.

So, if the financial hole is as big as projections indicate, and if the program is as important to people as they say it is, why hasn’t Congress closed the gap?

So, if the financial hole is as big as projections indicate, and if the program is as important to people as they say it is, why hasn’t Congress closed the gap? The answer is simple: Closing the gap requires members of Congress to subject themselves to political pain—raising taxes people would rather not pay or cutting benefits people want to keep. Few current elected officials will be around in the 2030s when the pain becomes inescapable. Rather than endure political pain now, senior members of each party are quite willing to wait, while graciously inviting their counterparts across the aisle to “show leadership” by proposing measures they know are unpopular.

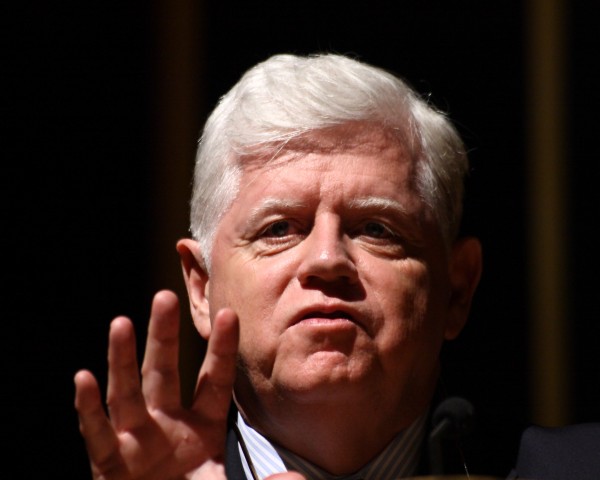

The chair and ranking member of the Social Security Subcommittee of the House Committee on Ways and Means have each introduced plans that would restore Social Security to sustainable solvency. But that is where their similarity ends. The plan proposed by Chairman Sam Johnson, a Texas Republican, would close the funding gap by cutting benefits—so much, in fact, that the cuts would allow cuts in the payroll tax. The plan proposed by the ranking Democrat, John Larson of Connecticut, would raise taxes more than enough to close the projected long-term funding gap and pay for benefit increases. Unsurprisingly, congressional leaders have shown no interest in pressing matters. As yet.

Such gracious procrastination will likely continue throughout the current presidential term. After cutting taxes and raising defense and domestic discretionary spending, Republican leaders have made clear that they would like to help offset projected budget deficits by cutting so-called entitlements, the largest of which is Social Security. But under Senate rules, changes to Social Security require 60 votes. No sentient being expects bipartisan collaboration to blossom in 2018, an election year. Or in 2019, when the next presidential campaign will be getting under way. Or in 2020, when the campaign will be in full swing. But major legislation on Social Security is possible in 2021, provided that there is a president and enough members of Congress who are prepared to negotiate constructive reforms. So, it is not too soon for progressives to think through the shape of a plan to restore Social Security to sustainable balance and modify it to take account of economic and social changes since 1983, when the last major legislation was passed.

The Social Security Financial Challenge

The challenge of Social Security reform is to close the long-term funding shortfall, while protecting the people of low and average means whose economic security depends on Social Security benefits, and adjusting the program to fit the changing conditions of American life.

A few numbers convey most of what one needs to know about Social Security’s financial future. According to current projections by its trustees, Social Security revenues will cover 84 percent of expenditures averaged over the next 75 years. An increase in revenues now of about one-fifth (16/84) or a cut in benefits of about one-sixth would close the projected gap. During those 75 years, however, the funding gap is projected to grow. Consequently, closing the average gap with adjustments that are more or less proportional over time would have an unfortunate side effect—after a few years, a new funding gap would emerge. That is just what happened after 1983 when a Democratic Congress and a Republican administration cut spending and raised taxes to close the funding gap projected over the next 75 years. Balance lasted exactly one year. The gap has grown primarily because of the passage of time, as later years with higher deficits entered the projection window. So, looking ahead today, fiscal balance in the 75th year will require somewhat more than the adjustments required to close the average gap.

Although progressives agree on the need to close Social Security’s long-term financial imbalance, many favor delay on the grounds that Congress will be forced to avoid benefit cuts and rely mostly on tax increases if it has to act on the eve of insolvency. At that time, they reason, a 3 or 4 percentage-point increase in payroll taxes for workers will be easier to pass than cuts of 20 percent or more for beneficiaries.

This view is both dangerously short-sighted and wrong. It is short-sighted because no one can reliably forecast the future balance of political forces, as recent events have reminded us. It is wrong because whenever Congress acts, it can make deep long-run cuts while sparing current beneficiaries and those soon to become beneficiaries. How? By borrowing to permit benefit reductions to be phased in over many years. The partial-privatization plans fashioned during the George W. Bush administration would have done just that, using government borrowing to sustain current benefits while payroll taxes were diverted into private accounts. But one need not point to defeated proposals. The current administration and Congress just showered generous payments—called tax cuts—mostly on the comparatively well-to-do, financed by borrowing.

Rather than passively waiting until the trust fund reserve is depleted, progressives should actively urge action to restore long-term financial balance as soon as the opportunity to negotiate a decent deal arises. Progressives cannot count on winning every element of their opening bid. So, they should start with a proposal that allows give and take while preserving a non-negotiable progressive core.

Sage Ross/Wikimedia Commons. Although the plan proposed by Representative John Larson of Connecticut would raise taxes more than enough to close the projected long-term funding gap and pay for benefit increases, congressional leaders have shown no interest in pressing matters.

THE CURRENT RETIREMENT income system enables most retired people to live with resources approximating what they had before retirement—an achievement, however, that will be at growing risk because of changes in private pensions. Social Security is the linchpin of the retirement system, the largest income source for most retirees, their survivors, and people with disabilities. Some retirees continue to work part-time, and some with low incomes also receive support from other federal programs, notably Supplemental Security Income and SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly Food Stamps). Medicare remains the main defense against the financial catastrophe of serious illnesses for all seniors, while Medicaid assists many with low incomes. Private pensions and personal savings are the largest sources of retirement income for higher earners.

Social Security offers a unique service: It is the only readily available source of fairly priced lifetime annuities, a stream of guaranteed income that will last as long as the beneficiary lives. Its benefits are fully protected from erosion by inflation. Traditional pensions with “defined benefits” (a specific monthly retirement benefit) also offer lifetime annuities, albeit with financial market risk and less complete inflation protection than Social Security’s or none at all. But traditional pensions started to disappear from private-sector jobs after 1974 when Congress, with the best of intentions, enacted legislation strengthening requirements for such plans that inadvertently led companies to abandon them entirely. By March 2017, traditional plans covered only 15 percent of all private industry workers, and the number was falling. Furthermore, many surviving plans were “frozen,” meaning that newly hired workers could not join them and many covered workers could no longer accrue credits. Instead, many employers established so-called 401(k) plans—essentially worker-owned savings accounts to which employers made a “defined contribution.” If the investments in 401(k) plans do poorly, the risk now falls on the employee, not the employer.

Roughly 70 percent of people age 65 or older have some sort of pension other than Social Security, which means, of course, that 30 percent of households have no private pension at all. Most benefits are not large. The medianvalue of all defined-contribution pension accumulations for people over age 65 in 2013 was $118,000, enough to pay an annuity of $581 per month to a 65-year-old woman. But such benefits are not indexed for inflation. (The mean 401(k)/IRAbalance was more than three times the median, which indicates that some of the elderly had much larger accumulations.) In contrast, the median Social Security benefit for a single worker, $1,294, was more than twice as high as the median for private accounts. Furthermore, Social Security benefits are not only fully indexed for inflation but also paid out in case of disability before retirement and to surviving spouses and children. Given the meagerness of other sources of retirement income for most workers, reforms should not reduce the proportion of their earnings that Social Security replaces.

In fact, because of economic and demographic developments, Social Security is not as progressive as it was. Benefit checks are net of Medicare premiums, which are uniform for most beneficiaries and have grown faster than benefits since the 1983 reforms. The 1983 legislation directly cut the ratio of retirement and survivor benefits to earnings. And even then, benefits were low compared with those of other developed nations.

In addition, demographic trends have made Social Security less progressive than in the past, measured by the lifetime value of benefits. Average life expectancies at birth rose from 74.7 years in 1985 to 79.2 years in 2017. But this gift of added life has accrued mostly to people with high earnings. The life expectancy of those born in 1920 who survived to age 50 was about five years longer for people in the top 10 percent in income than that for people in the bottom income decile. Among those born two decades later, in 1940, the gap in life expectancy widened to approximately 11 years. For those in the bottom income decile, life expectancy remained approximately flat.

Social Security itself needs improvement—low-income people aren’t benefiting as much as they did in the past.

The story that these numbers tell is complex, but clear. Social Security is and will almost certainly remain the foundation of income for low- and moderate-earning workers, people with disabilities, and survivors of deceased workers. When they retire, those with comparatively high incomes in the future will, as now, have to rely on income sources other than Social Security to sustain living standards. For the mass of the population, and especially for those with below-average earnings, current trends do not indicate that private pensions will significantly supplement Social Security. But Social Security itself needs improvement—low-income people aren’t benefiting as much as they did in the past. So, while addressing the financial shortfall, Congress should make other changes to help Social Security continue to provide continuity of income for retirees, surviving dependents, and the disabled.

A Progressive Social Security Agenda

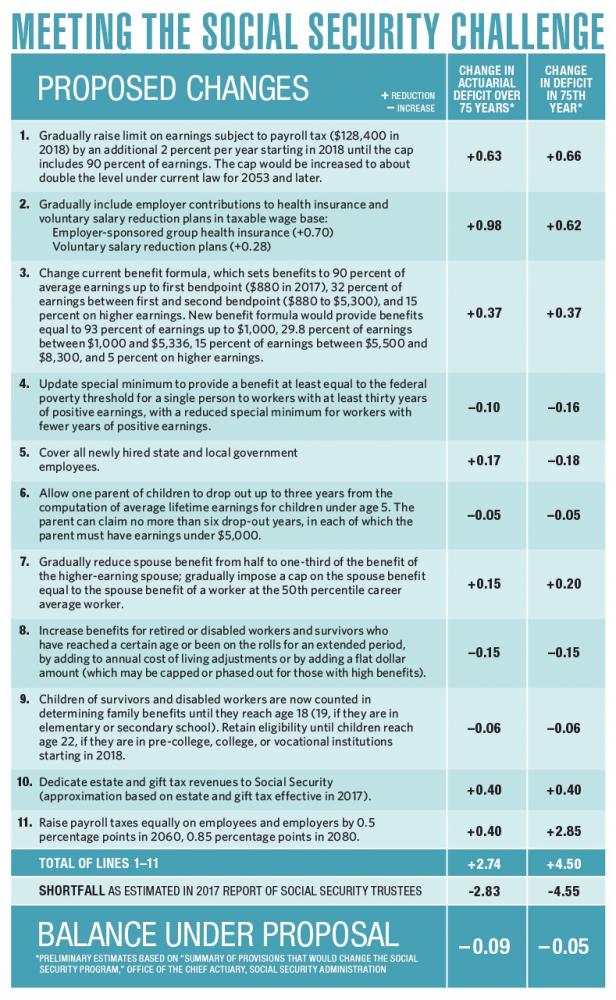

A progressive agenda for Social Security reform should achieve three core goals. First, it should restore actuarial balance averaged over the next 75 years and align revenues and expenditures through the end of the projection period, without cuts for most workers. Second, it should restore the progressivity of Social Security that economic and demographic trends have eroded. And third, to the extent feasible, it should adjust to ongoing economic and social changes. Here is an outline of how to accomplish those goals.

Restoring and Sustaining Balance. The key to putting Social Security back in long-term balance is to recognize that reforms need to correct for the diminishing proportion of employee compensation subject to Social Security taxes. That share has fallen for two reasons: growing income inequality and increases in non-cash compensation.

Since its inception, Social Security taxes have applied to a capped earnings base. The reason for the cap remains compelling. When workers have paid taxes on the earnings used to compute their benefits, they feel they have earned their benefits through work. Benefits come without the stigma attached to “welfare.” Furthermore, the full progressive legislative agenda contains much in addition to Social Security, and the government’s taxable capacity is limited. That taxable capacity should be devoted to assuring basic income, not spent on meeting all pension needs of the highly compensated. Applying the payroll tax to all of the earnings of most workers, but not to all earnings of the highly compensated, achieves these purposes.

On average, however, only the top 10 percent of earners have seen significant earnings growth in recent decades, which means that most increases in real earnings have flowed to those who earn more than the Social Security payroll tax ceiling. Although the wage ceiling does rise, the proportion of total earnings above it has nonetheless increased since 1983 from 10 percent to 17 percent, thereby eroding the tax base available to fund Social Security. Raising the payroll tax ceiling somewhat faster than current annual adjustments would gradually undo the erosion of the tax base due to growing earnings inequality. Such an increase in the tax base, combined with changes in the benefit formula to make it more progressive, would close more than one-third of the long-term funding gap.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert. The last major assault on the program, George W. Bush’s 2005 proposal to replace Social Security by diverting revenues into private accounts, turned into a political train wreck. Here, Bush participates in a 2005 roundtable discussion on Social Security at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas.

Since the Social Security payroll tax applies only to cash earnings, it does not cover employer contributions to health insurance, nor does it apply to compensation under certain “salary-reduction agreements” that pay for health care or child care. These once-minor forms of compensation have grown much faster than cash wages. The result is a widening divergence between the taxable wage base and total worker compensation. Excluding fringe benefits and salary-reduction agreements from tax is also inequitable. Two workers with identical total compensation face different taxes and will receive different Social Security benefits depending on whether they receive health insurance as a fringe benefit or buy coverage themselves. Broadening the tax base would align treatment of similarly compensated workers. This step would close nearly one-third of the currently projected average funding gap.

An additional step that will help close the funding gap is to make Social Security genuinely universal. For a variety of political and administrative reasons, the program initially covered barely half of the workforce. Gradually, Congress extended Social Security so that now almost all jobs are covered. The major remaining exceptions are roughly six million state and local government job slots in four states. Most workers in those jobs are thought to eventually earn Social Security coverage in other jobs. But the remaining exclusions produce needless complexity and leave some gaps in coverage. Bringing those excluded jobs into the system will help the program’s finances.

Restoring Social Security’s Progressivity. Several changes would partially offset the recent trends eroding the progressivity of Social Security benefits. The most direct step is to change the basic benefit formula to increase generosity at the bottom of the earnings scale. A second step is to liberalize a provision enacted in 1972 to award a special minimum benefit, higher than that produced by the basic benefit formula, to workers with lengthy, low-earning careers. Over time, the real value of the special minimum has remained constant, while average real earnings and monthly benefits for new retirees have increased. Consequently, the special minimum no longer provides extra assistance to the groups it was intended to help. Boosting the special minimum benefit to restore its availability to workers with lengthy low-wage careers is overdue.

Different versions of these two changes have been part of proposals introduced as draft legislation by both conservatives and progressives. Unsurprisingly, conservatives have opted for smaller “tilts” in the formula for low earners and smaller increases in the special minimum benefit than progressives do. But joint interest in these proposals by members of both parties is a favorable augury for future negotiations.

An additional change ought to address the difficulties facing many people who start retirement with adequate resources but after many years find their income eroding. They may cease to be able to work part-time for pay, use up their personal savings, and see inflation erode the purchasing power of their private pensions. For long-term retirees with limited incomes, therefore, some increase in Social Security benefits is warranted. Various commissions have suggested a bump up in benefits for people over a particular age—say, age 85. This approach, however, would do nothing for long-term Disability Insurance beneficiaries, while raising benefits even for the more affluent. A better approach would be to raise benefits for those who have been on the rolls for more than a certain period—say, 20 years. The increase could be proportional to initial benefits or capped. Or the bump in benefits could be set at a flat dollar amount and phased out for those with high benefits or high current income.

Another progressive step would help children who receive support as dependents of deceased or disabled Social Security beneficiaries. Those benefits now end at either age 18 or age 19 if the child is a full-time student who has not graduated high school. Given the importance of post-secondary education, eligibility should continue for children up to age 22 if they are in school.

Responding to Economic and Social Trends. Several other changes in Social Security are desirable, particularly to reflect changes in family life. When Social Security benefits began, the one-earner couple was an American norm. Most husbands worked for pay outside the home, and most wives did not. Because two cannot live as cheaply as one, Congress awarded one-earner couples a benefit half again larger than that paid to a single person with the same earnings. Each member of a married couple is entitled to the larger of a pension based on his or her earnings or a “spouse benefit” equal to half of the benefit of his or her married partner. This provision produces an unwanted side effect: Work of the lesser earner in a couple does not increase the couple’s pension until the lesser earner’s benefit exceeds half of the greater earner’s benefit.

Work for pay by both spouses is now the norm. As a result, retirement benefits for an increasing proportion of women are based on their own earnings histories—63.5 percent of women age 65 to 69 in 2016, up 20 percentage points since 1998. This trend is certain to continue. Spouse benefits are rapidly becoming a reflection of a bygone male-breadwinner world. These trends in no way diminish the continued importance of survivor benefits, which remain important for both men and women.

With men and women now working at similar rates, if not yet at equal average wages, it is time to reduce reliance on the spouse benefit. Capping the spouse benefit and indexing it only for inflation would preserve it in the near-term for couples with one low-earner but would allow a gradual transition to a system where eventually everyone’s benefit would depend on what he or she has earned.

Social Security should, however, also be adjusted to reflect unpaid labor in the home. Parents, especially those with modest incomes, often face wrenching choices about whether to sacrifice earned income to care for young children. Under current law, earnings loss also lowers future Social Security benefits. Publicly financed day care is probably the best solution to both of these problems. But that approach is costly, and the nation has not adopted it. Allowing people to omit years spent out of the labor force rearing young children when computing their lifetime average earnings would help. So would awarding a notional wage for years spent out of the labor force caring for children. Both approaches would help maintain Social Security benefits for those who leave the labor force to care for children. Designing such provisions is tricky, but neither is costly, and both somewhat lighten the long-term financial burden of parenting.

Promoting Long-Term Stability

The measures I’ve outlined, taken together, will eliminate most of the average funding gap for the next 75 years. But the financial impact of these measures is spread roughly proportionately over the period, while Social Security spending will rise faster than revenues. If nothing else is done, a small average gap would remain, which will tend to grow as the 75-year projection windows advance, as it did after the 1983 legislation. So, other steps should be taken to achieve continued balance.

Two additional measures would balance Social Security for the indefinite future under the economic and demographic assumptions the trustees now project. The first is an increase in the payroll tax levied on both workers and employers (0.5 percentage points in 2060 and 0.85 percentage points in 2080, or phased in as needed) to assure that the Social Security trust fund maintains adequate balances indefinitely. Revenue from the estate and gift tax under provisions prevailing before enactment of the 2018 tax law should also be dedicated to the Social Security trust fund.

Many conservatives oppose any tax increases, favoring instead a gradual increase in the normal retirement age. The average increase in life expectancy gives this change some surface appeal. But it is ill-conceived because less-affluent Americans haven’t seen increases in longevity. Another superficially attractive alternative would be to raise the age at which workers can first claim Social Security retirement benefits—currently age 62. This step seems in accord with the increase in labor force participation by people over age 65, up by half between 1994 and 2014. Most of this increase, however, has been among the well-compensated and better-educated, who comprise a growing share of the workforce. Raising the age for early retirement would impose unmistakable hardship on older workers for whom work has become too demanding, physically or mentally, who are sick, or who do not have long to live.

And contrary to what one might think, raising the age of initial entitlement slightly worsens Social Security’s long-term financial condition. Because benefits are scaled to the age at which benefits are claimed, no long-term savings result from raising the age at which retirement benefits can be claimed. But blocking early retirement benefits would cause some affected to apply for and be approved for disability benefits, increasing overall program costs for this group. In addition, rising average life expectancies have made the increment in benefits for delayed retirement a bit more than actuarially fair. For the average worker, it pays to wait to claim benefits as long as possible. So by forcing some people to claim benefits at a later age, raising the age of initial eligibility boosts average lifetime benefits.

Together, the various benefit and revenue changes I have outlined would place Social Security on solid financial footing for the foreseeable future. Of equal importance, they would respond to demographic, social, and economic developments that have emerged since Congress last enacted major Social Security legislation a generation ago. To delay restoring Social Security to long-term sustainability is to play Russian roulette with the keystone of progressive social policy in America. The time to restore the program’s finance balance will come when political balance is restored. That won’t be until at least 2021. But now is the time to think through the alternatives, to be clear about priorities, and to design a practical plan for the future.

Henry J. Aaron is a Senior Fellow in the Economic Studies department at the Brookings Institution.

From its inception, the Prospect has had a prescriptive focus that distinguishes it from many other publications. (Read the original 1989 prospectus for the magazine.) We look for articles that make sense of the world and illuminate what could be done to repair it. Much of what we publish concerns the relation between policy and politics: how to build public support for policies that serve the greater good. We pay particular attention to efforts to renew American democracy and civic life and to revitalize the social movements that can help achieve a more just society.

The Prospect also seeks to develop young writers, in part through the Writing Fellows program that we established in 1997. We take as much pride in the young journalists who started out at the magazine as we do in the many well-recognized figures whose work appears in our pages.

Independently published on a nonprofit basis, the Prospect earns some of its income from subscriptions and advertising but also depends on grants and individual donations. If you like what you read here, please subscribe or contribute.