A Crispr Conundrum: How Cells Fend Off Gene Editing

Human cells resist gene editing by turning on defenses against cancer, ceasing reproduction and sometimes dying, two teams of scientists have found.

The findings, reported in the journal Nature Medicine, at first appeared to cast doubt on the viability of the most widely used form of gene editing, known as Crispr-Cas9 or simply Crispr, sending the stocks of some biotech companies into decline on Monday.

Crispr Therapeutics fell by 13 percent shortly after the scientists’ announcement. Intellia Therapeutics dipped, too, as did Editas Medicine. All three are developing medical treatments based on Crispr.

But the scientists who published the research say that Crispr remains a promising technology, if a bit more difficult than had been known.

“The reactions have been exaggerated,” said Jussi Taipale, a biochemist at the University of Cambridge and an author of one of two papers published Monday. The findings underscore the need for more research into the safety of Crispr, he said, but they don’t spell its doom.

“This is not something that should stop research on Crispr therapies,” he said. “I think it’s almost the other way — we should put more effort into such things.”

Crispr has stirred strong feelings ever since it came to light as a gene-editing technology five years ago. Already, it’s a mainstay in the scientific tool kit.

The possibilities have led to speculations about altering the human race and bringing extinct species back to life. Crispr’s pioneers have already won a slew of prizes, and titanic battles over patent rights to the technology have begun.

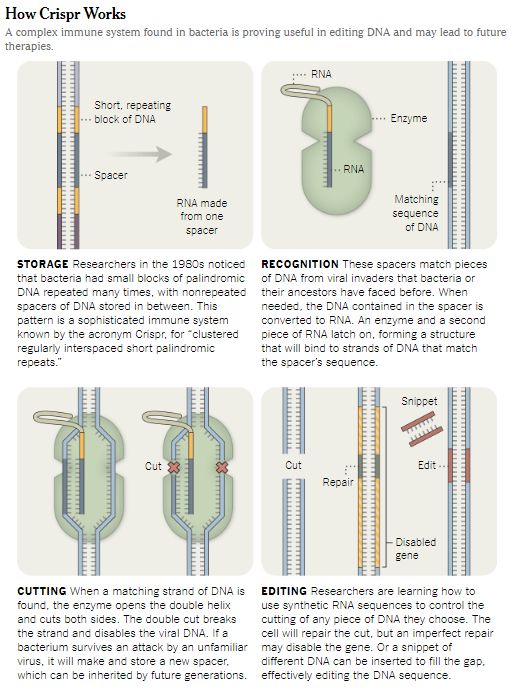

The New York Times | Sources: Nature; Addgene

To edit genes with Crispr, scientists craft molecules that enter the nucleus of a cell. They zero in on a particular stretch of DNA and slice it out.

The cell then repairs the two loose ends. If scientists add another piece of DNA, the cell may stitch it into the place where the excised gene once sat.

Recently, Dr. Taipale and his colleagues set out to study cancer. They used Crispr to cut out genes from cancer cells to see which were essential to cancer’s aggressive growth.

For comparison, they also tried to remove genes from ordinary cells — in this case, a line of cells that originally came from a human retina. But while it was easy to cut genes from the cancer cells, the scientists did not succeed with the retinal cells.

Such failure isn’t unusual in the world of gene editing. But Dr. Taipale and his colleagues decided to spend some time to figure out why exactly they were failing.

They soon discovered that one gene, p53, was largely responsible for preventing Crispr from working.

p53 normally protects against cancer by preventing mutations from accumulating in cellular DNA. Mutations may arise when a cell tries to fix a break in its DNA strand. The process isn’t perfect, and the repair may be faulty, resulting in a mutation.

When cells sense that the strand has broken, the p53 gene may swing into action. It can stop a cell from making a new copy of its genes. Then the cell may simply stop multiplying, or it may die. This helps protect the body against cancer.

If a cell gets a mutation in the p53 gene itself, however, the cell loses the ability to police itself for faulty DNA. It’s no coincidence that many cancer cells carry disabled p53 genes.

Dr. Taipale and his colleagues engineered retinal cells to stop using p53 genes. Just as they had predicted, Crispr now worked much more effectively in these cells.

A team of scientists at the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Mass., got similar results with a different kind of cells, detailed in a paper also published Monday.

They set out to develop new versions of Crispr to edit the DNA in stem cells. They planned to turn the stem cells into neurons, enabling them to study brain diseases in Petri dishes.

Someday, they hope, it may become possible to use Crispr to create cell lines that can be implanted in the body to treat diseases.

When the Novartis team turned Crispr on stem cells, however, most of them died. The scientists found signs that Crispr had caused p53 to switch on, so they shut down the p53 gene in the stem cells.

Now many of the stem cells survived having their DNA edited.

The authors of both studies say their results raise some concerns about using Crispr to treat human disease.

For one thing, the anticancer defenses in human cells could make Crispr less efficient than researchers may have hoped.

One way to overcome this hurdle might be to put a temporary brake on p53. But then extra mutations may sneak into our DNA, perhaps leading to cancer.

Another concern: Sometimes cells spontaneously acquire a mutation that disables the p53 gene. If scientists use Crispr on a mix of cells, the ones with disabled p53 cells are more likely to be successfully edited.

But without p53, these edited cells would also be more prone to gaining dangerous mutations.

One way to eliminate this risk might be to screen engineered cells for mutant p53 genes. But Steven A. McCarroll, a geneticist at Harvard University, warned that Crispr might select for other risky mutations.

“These are important papers, since they remind everyone that genome editing isn’t magic,” said Jacob E. Corn, scientific director of the Innovative Genomics Institute in Berkeley, Calif.

Crispr doesn’t simply rewrite DNA like a word processing program, Dr. Corn said. Instead, it breaks DNA and coaxes cells to put it back together. And some cells may not tolerate such changes.

While Dr. Corn said that rigorous tests for safety were essential, he doubted that the new studies pointed to a cancer risk from Crispr.

The particular kinds of cells that were studied in the two new papers may be unusually sensitive to gene editing. Dr. Corn said he and his colleagues have not found similar problems in their own research on bone marrow cells.

“We have all been looking for the possibility of cancer,” he said. “I don’t think that this is a warning for therapies.”

“We should definitely be cautious,” said George Church, a geneticist at Harvard and a founding scientific adviser at Editas.

He suspected that p53’s behavior would not translate into any real risk of cancer, but “it’s a valid concern.”

And those concerns may be moot in a few years. The problem with Crispr is that it breaks DNA strands. But Dr. Church and other researchers are now investigating ways of editing DNA without breaking it.

“We’re going to have a whole new generation of molecules that have nothing to do with Crispr,” he said. “The stock market isn’t a reflection of the future.”

Carl Zimmer is an award-winning New York Times columnist and the author of 13 books about science. His newest book is She Has Her Mother’s Laugh: The Powers, Perversions, and Potential of Heredity.