The Real Driver of Health Care Spending

THE HEALTH CARE DEBATES that occurred in Washington over the past year were largely irrelevant to what’s happening in the health care marketplace. Republicans couldn’t repeal the Affordable Care Act but they made some changes that weakened it. Those changes will increase insurance premiums in the individual market but they do nothing to address the most significant trends that are evolving across the system. To understand the important trends, one must look elsewhere.

In March, three researchers from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health published a study in JAMA analyzing the well-known reality that the United States spends dramatically more on health care than other wealthy countries. They compared the US, where health care consumes 17.8 per cent of gross domestic product, to 10 comparable nations where the mean expenditure is 11.5 percent. Despite spending much less, the other countries provide health insurance to their entire populations and have outcomes equal to or better than ours. The researchers found that this inefficiency gap is primarily driven by two characteristics of the US system: the high cost of pharmaceuticals and inordinate administrative expenses.

For example, annual per capita pharmaceutical expenditure in the US is $1,443 as compared to an average of $749 in the 10 other countries. Our administrative costs consume 8 percent of total spending as compared to a range of 1 to 3 percent elsewhere. No one else is close on either of these measures.

The high administrative spending derives in large part from the fact that 55 percent of the people in the US are covered by private health insurers who embed their own billing requirements, expenses, and profit into the system. The next highest country in this regard is Germany, where 10.8 percent of the population is covered by private insurers. In many countries, there are no such middlemen.

Coincidentally, when the JAMA study was published, the large publicly traded health care companies that dominate the US market had just finished disclosing their 2017 financial results. Examining those results provides additional insight into the economic forces that make our system so expensive and inefficient. The scale of the money involved is sometimes hard to grasp. The largest health care corporations, those included in the S&P 500, had almost $2 trillion in revenue last year. (Table 1)

Most of these enormous companies are engaged in one of two businesses: they’re either selling drugs or they’re selling health insurance. The excess costs reported by the Harvard researchers serve mainly to support the revenue of the companies in those fields.

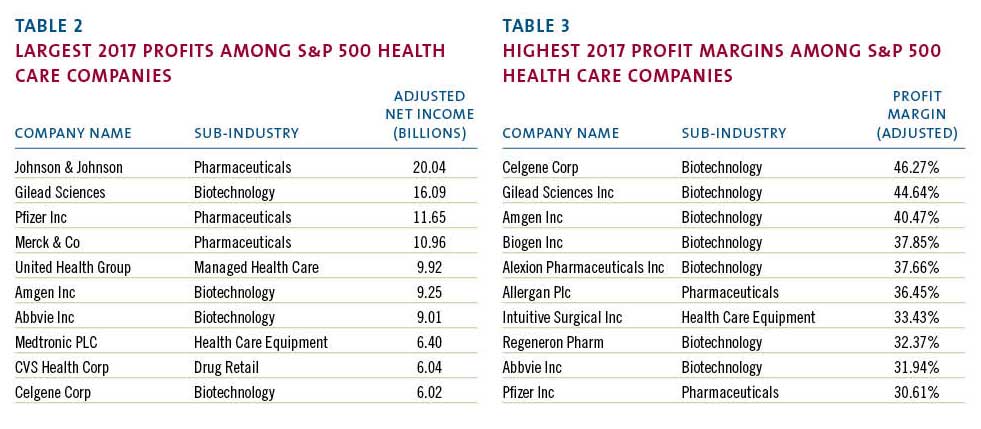

The 2017 reporting of corporate profits was complicated by the passage of the new tax bill. But most companies also reported “adjusted net income,” which shows their normalized profits after accounting for the one-time impact of the tax law. The chart below (Table 2) uses the adjusted numbers to show the largest annual profits among S&P health care companies.

Health insurers such as United Health and retailers such as CVS have enormous revenue and impressive profits but, when profit is measured as a percentage of revenue, they can’t compete with biotech and pharma. The highest relative profitability, using the same reported adjusted results, is in the chart below. (Table 3)

These profit margins show that there are many situations where between a third and a half of every dollar spent on a prescription drug falls to the bottom line of the of the company that made it. This profit derives in large part from the enormous difference in drug prices in the US versus other countries where such prices are more effectively controlled.

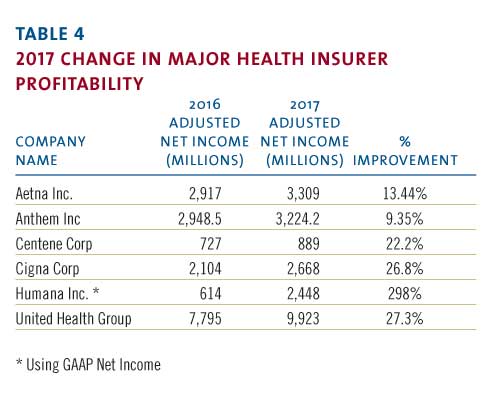

The high administrative cost of the US system stems from the large portion of the market dominated by insurance companies looking to maximize their profits. Notwithstanding many news stories about turmoil in the insurance markets, 2017 was a banner year for the largest health insurers. The big players all had significant increases in annual profitability in 2017.

Note that Humana did not report “adjusted” numbers even though its profit was swollen by unusual events. A major distortion was a huge break-up fee the company received from a failed merger. That accounted for approximately $630 million in after-tax profit. Even discounting that, it was a very good year.

The revenue and profitability of these corporations support the proposition that high pharmaceutical prices and insurance-related administrative costs account for much of the extraordinary expense of our system. US health policy, or the absence thereof, has enabled these businesses annually to drive costs up for the benefit of their bottom line. That effect will continue. Not surprisingly, the big health care companies are developing new strategies to enhance their businesses and drive their profits going forward.

The term now heard often among health care giants is “vertical integration,” which means combining upstream suppliers with downstream buyers to control the flow of business. If this strategy persists, health care delivery will evolve significantly although it is unlikely to become less expensive. The most prominent current example of vertical integration is the planned $68 billion acquisition of Aetna by CVS.

How would these companies work together? A Wall Street analyst recently described the vision as a way to “identify high risk patients and preemptively get them into a Minute Clinic.” Thus, your health insurer could send you to a local store for diagnosis, treatment, drugs, and anything else you might need from the shelves. This will keep even more of the health care dollar under their control.

Similarly, Cigna is in the process of acquiring Express Scripts, a huge pharmacy benefits manager, for $54 billion, another attempt to bring more services under one roof. The combined company would have annual revenue of $142 billion and, presumably, enough leverage with drug companies to improve profits although not necessarily to lower costs to patients. United Health, a leader of vertical integration, previously bought a pharmacy benefit manager but co-pays and deductibles for its patients have continued to climb. United has aggressively acquired physician practices in recent years and is now in the process of buying DaVita Medical Group, which operates nearly 300 clinics and outpatient surgical centers.

More striking are reports of a potential but unsigned merger of Walmart and Humana, a combined company that would have revenue of $550 billion. Walmart is a large operator of retail pharmacies inside its stores and the logic is similar to the Aetna-CVS deal. Humana, a huge insurer, is separately in the process of acquiring a large home health business from Kindred so this could represent yet another level of vertical integration.

If this course continues, the health care system will evolve quickly, giving fewer and larger companies even more market leverage. Integration of this kind benefits the large corporations that initiate it but there is no evidence it will lead to lower costs, improved access, or enhanced quality. These changes are driven by highly focused corporate financial interests and are occurring without reference to public policy. That’s because there is no coherent public policy to guide these changes.

On May 11, President Trump made a long-awaited speech to reveal what he described as “the most sweeping action in history to lower the price of prescription drugs for the American people.” His typically firebrand language struck at “drug makers, insurance companies, distributors, pharmacy benefit managers, and many others” who contributed to “this incredible abuse.” His attack seemed to target the large public companies that have benefited from the abuse. Unsurprisingly, his speech did not include specifics. His staff then released tepid policy details, which immediately generated a significant upward spike in the biotech stock index as well as the stock prices of other large health care companies. For all the presidential bombast, investors saw Trump’s policy for what it is: indifference to the current path and no threat to high prices.

It is not in the interest of huge profit-making corporations to restrain the overall cost of the US health care system. In fact, their interest is served by driving health care expenditures higher. When combined with the spending analysis provided by researchers, the financial data disclosed by public corporations point to a path that the country must follow to make our system more coherent and less costly. Any progress will require driving down pharmaceutical pricing and reducing administrative costs imposed by middlemen. We are not doing that yet but, ultimately, we must.

Edward M. Murphy worked in state government from 1979-1995, serving as the commissioner of the Department of Youth Services, commissioner of the Department of Mental Health, and executive director of the Health and Educational Facilities Authority. He recently retired as CEO and chairman of one of the country’s largest providers of services to people with disabilities. The author is grateful for the assistance of Zachary Curtis in gathering financial information for this article. Curtis graduated in May from the business school at Bridgewater State University where Murphy is a trustee