Electric Vehicles Are Gaining Momentum, Despite Trump

The transportation sector today emits more carbon than any other sector of the US economy. And it is shaping up to be the next big battle in the long fight to decarbonize.

On one side of that battle: the Trump administration, a few US automakers, and Koch Industries, who would like to stymie or at least delay the electrification of vehicles and continue the use of fossil fuels.

On the other side: California, a coalition of like-minded states, most automakers, a growing roster of utilities, and climate hawks. All of them are eager to accelerate the shift to electric vehicles (EVs), so that the sector can be run on increasingly clean grid power.

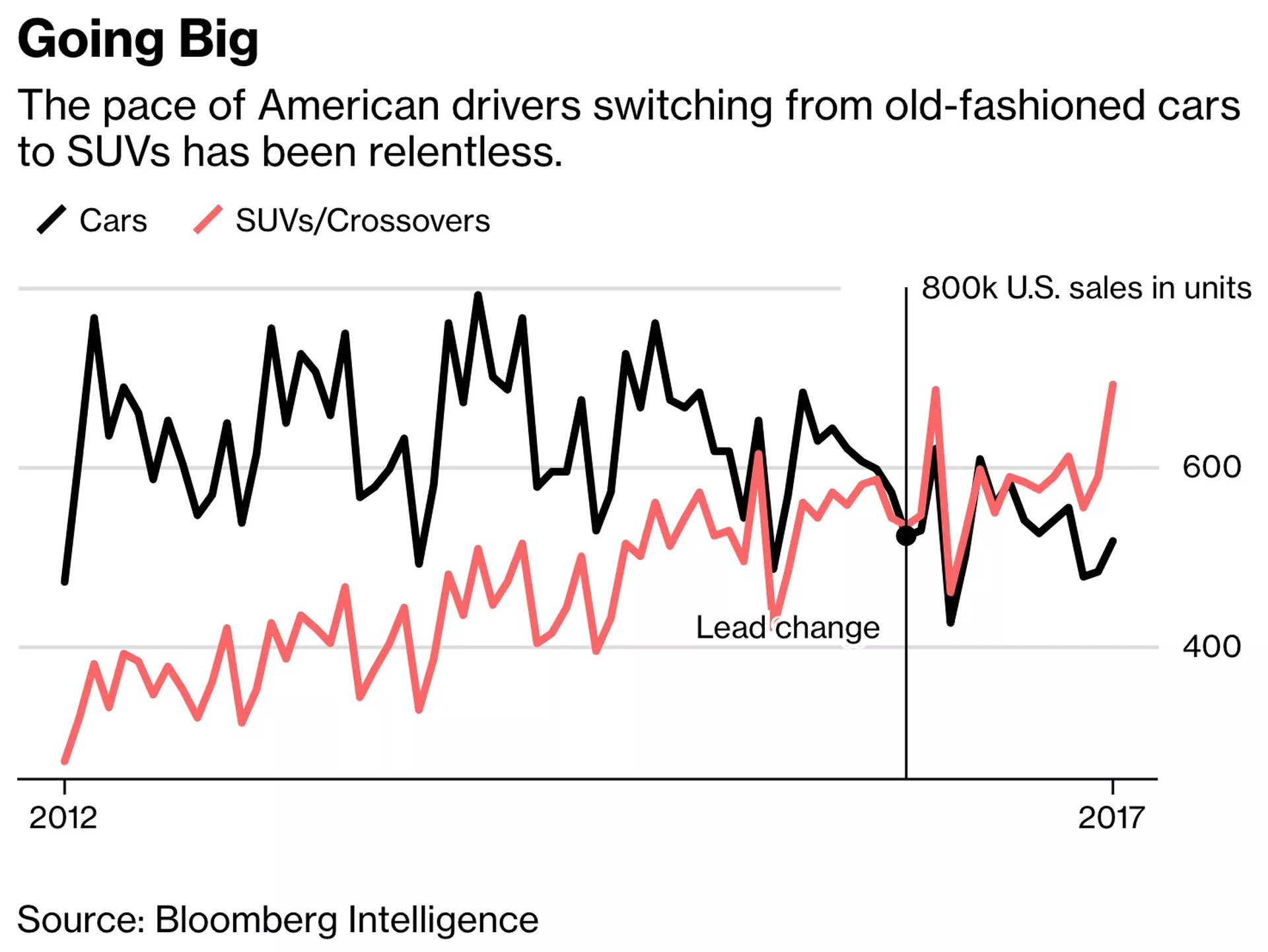

Lately, the Trumpian side has had the upper hand. Former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt signaled that he wanted to freeze fuel-economy standards at 2020 levels, while Koch-funded groups are fighting EV incentives and blocking public-transit projects around the country. And low oil prices have kept gas prices down, which means American consumers are once again opting for SUVs and trucks. Cars are practically disappearing from the market; Ford plans to stop selling almost all its cars by 2020.

But underneath the surface, there is a frenzy of activity on the other side. It’s not just that states are pushing back and beginning to set their own stringent goals (like California’s, to put 5 million EVs on the street by 2030). It’s also that a broader coalition is taking on the real nuts and bolts of electrifying the US fleet, working out the details and best practices that will be necessary to put ambitious plans into motion.

Though only about 1 percent of US vehicles are electric today, and many consumers have not researched or even heard of EVs, some forecasts have them as high as 65 percent of new US vehicle sales in 2050. We are on the front end of a steeply rising S-curve, a rate of change not seen in the US transportation sector for decades. The temporary triumphs of the luddites in power should not obscure the fact that the work of making those forecasts real is beginning in earnest.

Let’s take a quick tour through some recent developments.

The feds and the California coalition are heading for an epic showdown over fuel economy standards

California and a coalition of 16 other states (and DC) — representing more than 140 million people and 40 percent of the US auto market — are suing the Trump administration over its plan to freeze fuel economy standards.

“You can’t just, like some tinhorn dictator, say I’m tearing up a rule that was built on two years of building up evidence,” said California Gov. Jerry Brown about the plan at a press conference in May.

If EPA does freeze the standards (Pruitt’s statement did not specify timing), California has a longtime exemption under the Clean Air Act, which allows it, and states that choose to join it, to set its own standards. In fact, California’s coalition was what dragged automakers to the table to work out the standards with President Barack Obama in the first place.

Currently, 12 states have adopted California’s standards; last week, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper announced that his state would join them. (The the Auto Alliance and the Colorado Chamber of Commerce promptly rolled out a state-wide misinformation campaignto try to block the move.)

Pruitt has said he might try to revoke California’s waiver, per the urging of a group of Koch-tied conservative groups. California has made it very clear it will fight any such attempt in court; lately, Pruitt has backed off.

If Pruitt does manage to freeze standards and force California to go along (which is unlikely), “there is no doubt that would slow down electrification,” Salim Morsy, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, told the LA Times. But if Pruitt fails, automakers will face the very nightmare they tried to avoid under Obama: a nation with two sets of standards, effectively two separate markets.

Since California and its growing coalition are unlikely to relent, it will eventually be the dirty market that gives way. Again.

Finally, some real money is going to vehicle charging infrastructure

While these legal battles brew, California is going full speed ahead on EV policy. Via executive orders, Brown has not only established a target of 5 million zero-emissions vehicles on California streets by 2030, he’s also targeted 250,000 zero-emission vehicle chargers, including 10,000 DC fast chargers, by 2025.

(In May, the California Energy Commission released a report estimating that the state will need “between 229,000 and 279,000 electric vehicle chargers at locations other than single-family homes by 2025 to meet the state’s goals for adoption of zero-emission vehicles.”)

You can't short-circuit industry progress. The conclusion is inescapable: California's vehicle future is electric drive ⚡️🚙🔋 https://t.co/82rgSH8SIr

— Mary Nichols (@MaryNicholsCA) January 18, 2017

Given consumers’ perpetual (if misguided) anxiety about the range of EVs, most analysts see charging infrastructure as the key to widespread EV adoption. The question is, who should pay to build and operate it?

There’s been trepidation about utilities owning EV chargers, questions about whether such investments serve all ratepayers and whether charging is better left to markets. Until 2016, California prohibited utilities from owning EV chargers. But chargers weren’t getting built, so the state reversed the prohibition and promptly approved plans for all three of the state’s utilities to being deploying thousands of charging stations.

This month, California was one of three states, along with New York and New Jersey, to announce a cumulative $1.3 billion worth of investment in charging infrastructure; California’s portion, $750 million to be spent (and charged to ratepayers) by the state’s utilities, was just approved by the California Public Utility Commission (CPUC).

As for New York and New Jersey, via the Verge:

In New York, the governor’s office announced a pledge of up to $250 million through 2025 to its electric vehicle expansion initiative, EVolve NY. The New York Power Authority will work with the private sector to install up to 200 DC fast chargers “along key interstate corridors” with the goal of making them available every 30 miles, and it will also bring them to urban areas as well, including at or near New York City’s two major airports. Meanwhile, New Jersey’s biggest utility owner Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG) announced a $300 million pledge to build out up to 50,000 charging stations along highways, in residential areas, and at workplaces.

This constitutes a substantial first step toward fully electrifying a few of the nation’s major metro areas and the highways linking them, enabling practical, anxiety-free EV ownership. It’s a base from which charging infrastructure can expand.

States are working out detailed EV roadmaps for the next few years

The Multi-State ZEV Task Force — established by the governors of California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont in 2013 — has released the second version of its “Multi State ZEV Action Plan.” It covers 2018 to 2021 and contains 80 detailed recommendations for ways that states can meet or exceed their ZEV targets.

Targeting recommendations at state regulators, automakers, dealers, and utilities, the plan calls for more purchase incentives, greater outreach and education for consumers and auto dealerships, conversion of state vehicle fleets to electric, and the buildout of charging infrastructure.

The recommendations are not binding, but they do constitute an extremely detailed path forward for the next three years of EV adoption.

A new coalition of automakers, utilities, and civic groups seeks a set of common EV principles

Speaking of road maps, last week also brought the introduction of the Transportation Electrification Accord, a list of principles meant to “educate policymakers on how to advance electric transportation in a manner that provides economic, social and environmental benefits.”

So far, signatories include GM and Honda, along with a wide range of service companies, utilities (including Exelon, operator of the nation’s largest nuclear fleet), labor groups, consumer advocates, and environmental groups. (Signatories endorse the principles, though they are not binding.) It was organized by Advanced Energy Economy, Energy Foundation, Illinois Citizen Utility Board, Natural Resources Defense Council, Plug-in America, and Sierra Club.

The principles are more abstract and comprehensive than the recommendations in the ZEV Action Plan. They include familiar concerns (more charging infrastructure; use of open, interoperable standards) along with a couple of provisions specifically targeted at utilities and utility regulators.

One of the trickiest issues in allowing utilities to build charging infrastructure is that they have to convince regulators to allow them to rate-base the investments — i.e., to charge all ratepayers equally for them. But consumer advocate groups often object to this, saying that such investments only benefit a relatively narrow and affluent class of EV owners. (The same problem often faces microgrid investments. This interesting piece by Lisa Cohn in Microgrid Knowledge explores the parallels and possible solutions.)

The Transportation Electrification Accord emphasizes that rate-based utility investments in EV infrastructure should, insofar as possible, benefit the whole grid and all ratepayers:

The build out of EVSE [electric vehicle supply equipment] must optimize charging patterns to improve system load shape, reduce local load pockets, facilitate the integration of renewable energy resources, and maximize grid value. Using a combination of time-based rates, smart charging and rate design, load management practices, demand response, and other innovative applications, EV loads should be managed in the interest of all electricity customers.

(See this report from Chris Nelder at RMI for more on best practices in building out EV charging infrastructure.)

This will be a recurrent question as distributed energy technology grows more common and varied, from batteries to solar panels to EVs and chargers. Which parts should utilities own? Which parts should they have visibility into or control over?

As energy tech gets smaller and more modular, it becomes more difficult to distinguish which ones benefit the whole grid versus those who own them. Utilities are scrambling to keep up with the changes.

Luxury EVs are going to be a huge market in the coming years

A few more reports, initiatives, and shifts in the market worth noting:

- The Sierra Club and Plug In America recently released the second version of their “Model State & Local Policies to Accelerate Electric Vehicle Adoption.” It is a menu of best practices for supporting at the state, city, and utility level. Notably, it has a whole section on “expanding equity and access,” which does not always get adequate attention.

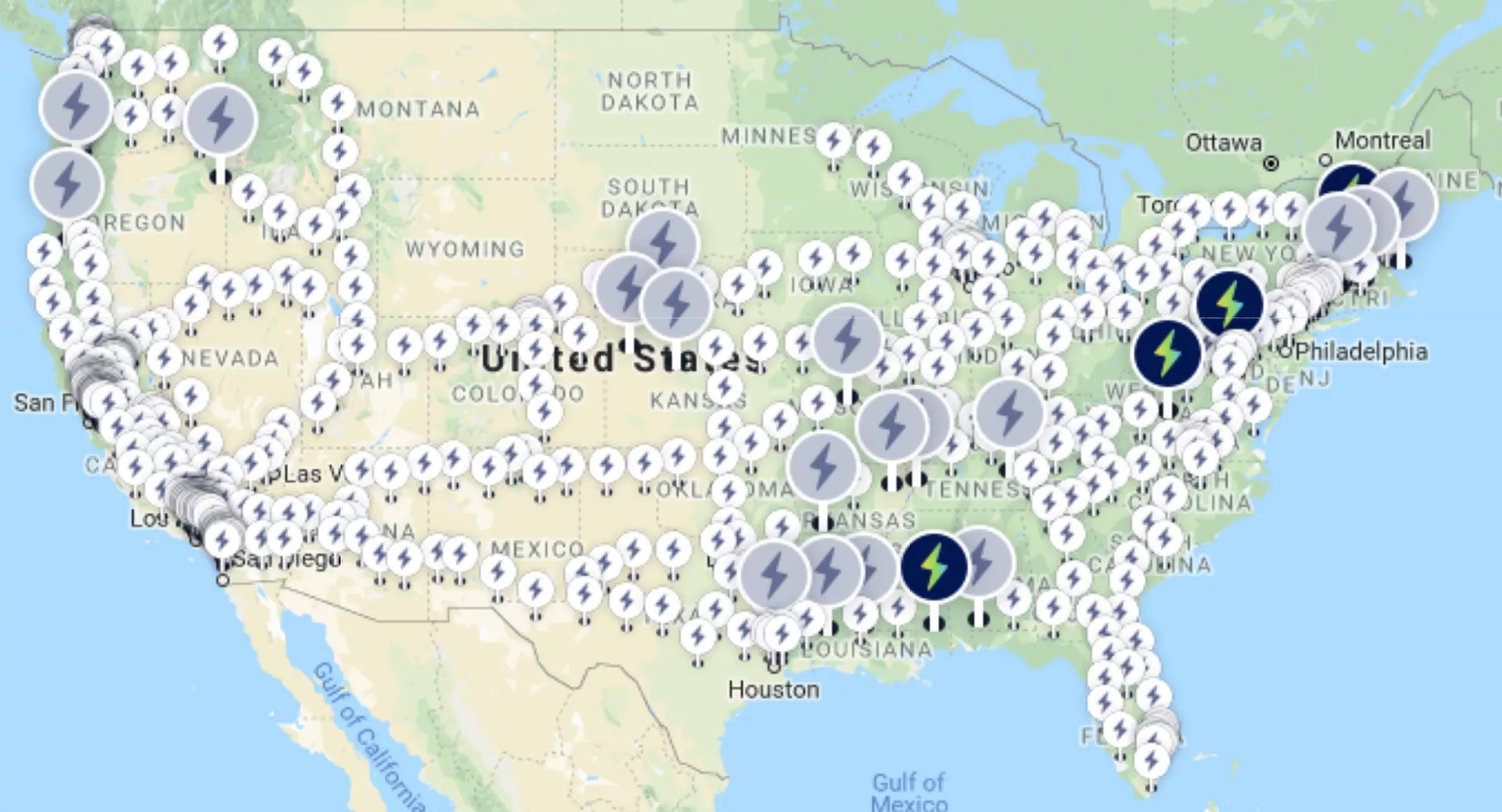

- Electrify America has a plan to invest $2 billion in ZEV infrastructure and consumer education between now and 2027. (Sacramento got $44 million earlier this month.)

Charging stations by Electrify America, built and planned. Electrify America

The Electrification Coalition, representing dozens of companies along the EV supply chain, releases a ZEV State Policy Scorecard, ranking states on support for ZEVs. For kicks, a quick summary: Tier 1 is California, Maryland, Connecticut; tier 2 is Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey; tier 3 is Vermont, Rhode Island, Oregon, Maine.

- Finally, two little bits of punctuation. First, this month brought news of two new high-end EVs: Jaguar Land Rover’s I-PACE, a burly off-road crossover, and Porche’s Taycan, a high-powered sedan. (How do automakers come up with these names?) Luxury EVs are going to be a huge market segment in coming years.

- Also, Uber, in one of its many bids to rehabilitate its public image, is rolling out a pilot program that will offer drivers incentives to switch to EVs. (As a reader notes, Uber has also joined Lyft in opposing a California EV bill.)

The EVs are coming, the EVs are coming

Despite the flailing of the Trump administration and backward-looking fossil-fuel supporters, momentum around electrification is reaching critical mass. EVs are about to ride up the S-curve into exponential growth. It is difficult to predict exactly when, but it is inevitable. All these infrastructure investments, the rear-guard battles against Trump and Koch, and most of all the increasingly detailed sharing of knowledge and replicable best practices — all of it is like a winding spring that is going to shoot the EV market into rapid motion over the next few years.

Politics is a dumpster fire and democracy may not survive, but by God, the EVs are coming. It’s really happening.

David Roberts writes about energy and climate change. Email. Twitter. Facebook. RSS.