Arrested, Jailed and Charged With a Felony. For Voting.

GRAHAM, N.C. — Keith Sellars and his daughters were driving home from dinner at a Mexican restaurant last December when he was pulled over for running a red light. The officer ran a background check and came back with bad news for Mr. Sellars. There was a warrant out for his arrest.

As his girls cried in the back seat, Mr. Sellars was handcuffed and taken to jail.

His crime: Illegal voting.

“I didn’t know,” said Mr. Sellars, who spent the night in jail before his family paid his $2,500 bond. “I thought I was practicing my right.”

Mr. Sellars, 44, is one of a dozen people in Alamance County in North Carolina who have been charged with voting illegally in the 2016 presidential election. All were on probation or parole for felony convictions, which in North Carolina and many other states disqualifies a person from voting. If convicted, they face up to two years in prison.

While election experts and public officials across the country say there is no evidence of widespread voter fraud, local prosecutors and state officials in North Carolina, Texas, Kansas, Idaho and other states have sought to send a tough message by filing criminal charges against the tiny fraction of people who are caught voting illegally.

“That’s the law,” said Pat Nadolski, the Republican district attorney in Alamance County. “You can’t do it. If we have clear cases, we’re going to prosecute.”

The cases are rare compared with the tens of millions of votes cast in state and national elections. In 2017, at least 11 people nationwide were convicted of illegal voting because they were felons or noncitizens, according to a database of voting prosecutions compiled by the conservative Heritage Foundation. Others have been convicted of voting twice, filing false registrations or casting a ballot for a family member.

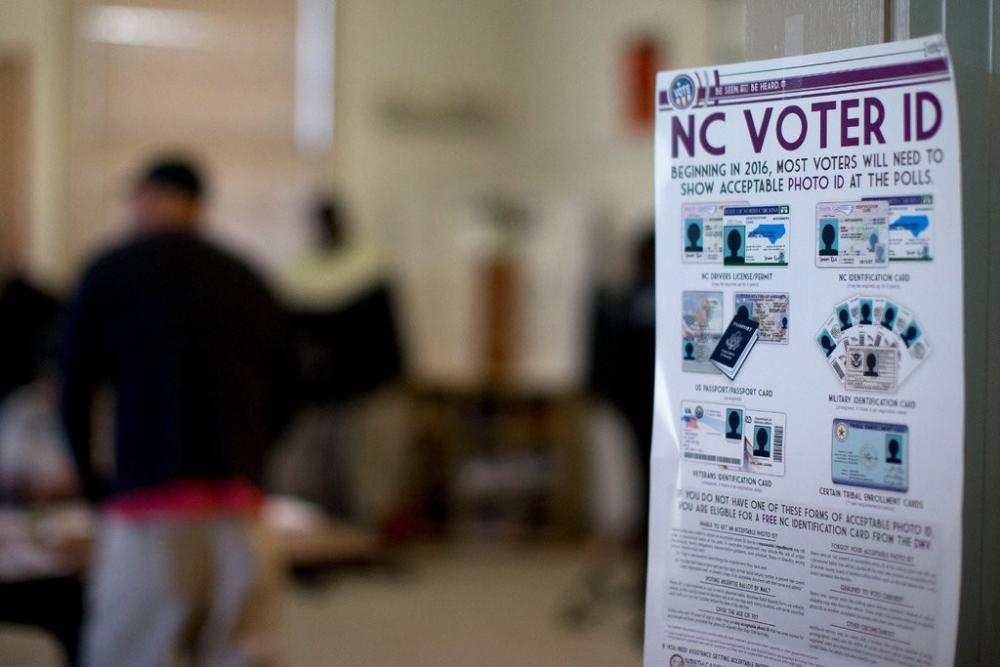

North Carolina voter ID rules posted at the door of a voting station in Greensboro, N.C., in March 2016. A federal appeals court has since blocked the law requiring voters to show identification.Credit: Andrew Krech/News & Record, via Associated Press

The case against the 12 voters in Alamance County — a patchwork of small towns about an hour west of the state’s booming Research Triangle — is unusual for the sheer number of people charged at once. And because nine of the defendants are black, the case has touched a nerve in a state with a history of suppressing African-American votes.

Local civil-rights groups and black leaders have urged the district attorney to drop the prosecution, saying that black voters were being disproportionately punished for an unwitting mistake. African-Americans in North Carolina are more likely to be disqualified from voting because of felony convictions; their rate of incarceration is more than four times that of white residents, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit organization.

“It smacks of Jim Crow,” said Barrett Brown, the head of the Alamance County N.A.A.C.P. Referring to the district attorney, he added, “I don’t think he targeted black people. But if you cast that net, you’re going to catch more African-Americans.”

Mr. Nadolski said that race and ethnicity are not a factor in any case he prosecutes.

The prosecution comes even as several states are reconsidering longstanding laws that strip voting rights from an estimated 6 million Americans who have been convicted of felonies. A growing national movement is encouraging former felons to register to vote, or to push to have their rights restored, with the hope of empowering them and shedding the stigma of criminal convictions.

[ Read a Q. and A. with Jack Healy about the case and American election law. ]

The North Carolina case also has become part of a partisan war over voting rights ahead of this November’s midterm elections. At a rally on Tuesday, President Trump — who has made baseless claims that millions of people voted illegally in 2016 — renewed his calls for laws requiring voters to show photo identification. He said, incorrectly, that shoppers need to show identification to buy groceries, while people voting for president and senator do not.

When asked Wednesday about the president’s comments, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said that Mr. Trump “wants to see the integrity of our elections system upheld.”

In separate interviews, five of the defendants in Alamance County said their votes were an unwitting mistake — a product of not understanding the voter forms they signed and not knowing the law.

Pat Nadolski, the Alamance County district attorney, says he is defending the integrity of the election system by prosecuting people who voted while on felony parole or probation.Credit: Travis Dove for The New York Times

They said they believed they were allowed to vote because election workers let them fill out voter registration and eligibility forms, then handed them ballots. They said they never would have voted if anyone had told them they were ineligible.

The case began after North Carolina elections officials ran an audit that found 441 felons had voted improperly in the 2016 election. While most local prosecutors did not pursue these cases, Mr. Nadolski decided to file felony charges.

“We want to maintain the integrity of the voting system,” Mr. Nadolski said.

Most of the voters did not know one another before the prosecution, but as they attended court together and as their story spread through this conservative county, people started referring to them as one: the Alamance 12.

Activists have protested outside the county courthouse and asked supporters to flood the district attorney’s office with letters and phone calls on the defendants’ behalf.

Whitney Brown, 32, said that no judge, lawyer or probation officer ever told her that she had temporarily lost her right to vote after she pleaded guilty to a 2014 charge of writing bad checks. Her sentence did not include prison time.

By November 2016, she was complying with her probation and focused on moving ahead with her life, caring for her two sons, who are now 6 and 9 years old, and taking online classes to become a medical receptionist. So when her mother invited her to come with her to vote for president, Ms. Brown said she did so without a second thought.

Months later, she got a letter from state election officials telling her she appeared to have voted illegally. “My heart dropped,” she said.

Taranta Holman, 28, had never voted before 2016. He spent years bouncing between low-paying jobs, criminal charges and probation.Credit: Travis Dove for The New York Times

In North Carolina, people’s voting rights are automatically restored once they finish every step of their felony sentence, including probation.

But every state is different. Vermont and Maine do not strip felons of voting rights, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Other states allow people to vote again as soon as they leave prison. Others permanently take away felons’ right to vote or make them ask to have their rights restored.

In North Carolina, people can be found guilty of voting as felons even if they did not know their status or did not mean to break any voting laws. This spring, lawmakers tried to pass a bill that would have added intent as an element of felon-voting crimes, but the bill died.

Like other voters across North Carolina, each of the Alamance 12 would have been required to sign a form saying they were eligible to vote and were not serving a felony sentence. But the defendants said they did not remember filling out any forms beyond the ballots.

“People get confused,” said John Carella, an attorney with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which is representing Ms. Brown and four other defendants. The group has also filed a motion in court arguing that North Carolina’s original 1901 law barring felons from voting is unconstitutional because it is steeped in racist efforts to keep African-Americans from voting.

After the state audit that found 441 felons had voted, North Carolina’s Board of Elections and Ethics Enforcement changed the layout of the voter forms, adding check boxes to make them easier to understand. The board said it was also working with courts and probation officials to make sure people are aware that they lose their voting rights while serving a felony sentence and probation.

Activists are now worried that the fear of prosecution may suppress black turnout in the midterm elections. North Carolina lawmakers have put a constitutional amendment on November ballots that would change the state constitution to require voter identification.

Activists have protested on behalf of the Alamance 12 outside the county courthouse, where defendants must walk past a Confederate monument on their way to hearings.CreditTravis Dove for The New York Times

An earlier law adding such a requirement was struck down in 2016 by a federal appeals panel, which called it “the most restrictive voting law North Carolina has seen since the era of Jim Crow.” The ruling said Republicans had targeted “African-Americans with almost surgical precision.”

George Lettley, who runs a popular catering hall in Alamance County with his wife Elois, said he saw the prosecutions as the latest example of a pattern of discrimination against African-Americans by white leaders in his state.

“They’re looking for any way they can find to stop any momentum we have,” said Mr. Lettley, reflecting on the case as he and his wife rested and polished silverware after dinner. “It’s a no-win situation for us.”

When he and his wife heard that one of the 12 defendants had lost his job and had been sleeping in his car, they hired him to work at their restaurant.

Taranta Holman, 28, said he had never voted before 2016. He spent years bouncing between low-paying jobs, criminal charges and probation, and he saw little incentive to vote for either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump.

But he said he voted at the urging of his mother. In December 2017, when news of the charges appeared in the local newspaper, Mr. Holman said that relatives called him to say there was a warrant out for his arrest.

“I thought they were playing with me,” he said.

Three of the defendants have taken deals pleading to lesser misdemeanors that come with probation and community service. For the moment, Mr. Holman was planning to fight the charges. He said he could not afford the fees that come with a probation sentence and did not want to stay under the scrutiny of the legal system.

“I feel like I’ve got a better chance with a jury than the D.A.,” he said.

But Mr. Holman said that, win or lose in court, he will never cast another ballot.

“Even when I get this cleared up, I still won’t vote,” he said. “That’s too much of a risk.”

Jack Healy is a Colorado-based national correspondent who focuses on rural places and life outside America's “City Limits” signs. He has worked in Iraq and Afghanistan for The Times and is a graduate of the University of Missouri’s journalism school. He adopted a street cat from Baghdad and still has the scars on his hands to prove it.