Trump, the Republican Party, and Westmoreland County

“Pennsylvania was key to Trump’s presidential victory, Westmoreland County was key to Pennsylvania, and District Seven was key to Westmoreland County.” Whether District Seven and Westmoreland County were as central to the 2016 election as Paul Verostko, President of District Seven’s Republican Party, claims, one thing is certain: both the district and the county are Trump territory. Before I sat down to talk with Verostko in March 2018, he invited me to meet him at “the Trump House.” Leslie Rossi, who identifies herself as “a very conservative Republican,” opened the house in the summer of 2016, not only as a visible display of her support for the Republican candidate, but also as a key distribution center for Trump gear. The house had “all the Trump materials you could imagine: hats, flags, t-shirts, bumper stickers,” Verostko told me, and supporters could “walk in the house and four items. All for free, no charge.”

In the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump obtained 63.5 percent of the vote to Hillary Clinton’s 32.5 percent in Westmoreland County. The county is now solidly red, but it hasn’t always been. I grew up in Westmoreland County in the 1960s and ‘70s, and despite my mother being a loyal, committed Republican, the county was solidly blue. When elections came around, I remember she would say to me, “Why do I even bother to vote? The Democrats always win!”

When and why Westmoreland County switched from a Democratic Party bastion to a Republican stronghold is a complicated question. To start to find the answer, it helps to look back to when the region’s party orientation first shifted the other way.

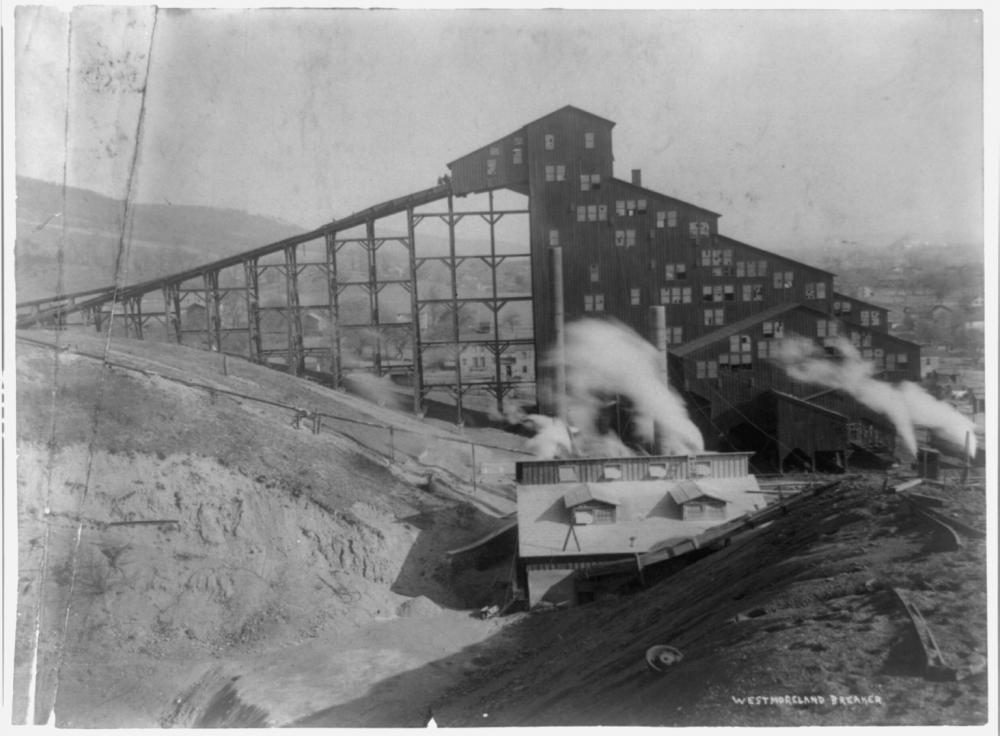

Photo: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons. // Political Research Associates

Westmoreland County: A Historical Overview

Westmoreland County is one of 10 counties that make up southwestern Pennsylvania. On a good day, Greensburg, the county seat, is about a 30-minute drive southeast of Pittsburgh. Most people outside the area have never heard of Greensburg, but they might be familiar with its neighbor, Latrobe, the home of Mr. Rogers, Arnold Palmer, and Rolling Rock beer.

From the late 1880s to the 1920s, Westmoreland County was coal country. The richest seam of bituminous coal in the world ran through Southwestern Pennsylvania. Bituminous coal is used to make coke, which was critical to fueling the steel mills that sprung up in nearby Pittsburgh and along the Monongahela River Valley. Steel—as Trump’s 2016 campaign promises hammered home—was the exemplary and essential product of an industrializing United States.

Henry Frick, Andrew Carnegie, and Andrew Mellon—all names associated with elite academic and cultural institutions today—amassed huge fortunes from the outsized profits they obtained as a result of their ownership of or investment in the coal, coke, and steel industries and related enterprises. Frick, who was born and raised in Westmoreland County, was known as the “Coke King” because he was the single largest owner of coke ovens in the area. When he died in 1919, he was worth what would be $3.9 billion in today’s money. Frick’s wealth, like much of Carnegie’s and Mellon’s, resulted from the exploited labor of the coal miners who burrowed deep underground to extract the coal and the workers who then distilled it into coke.

Tens of thousands of Catholic immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe streamed into southwestern Pennsylvania to labor in the coal mines and at the coke ovens in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Forced to live in the company towns (known locally as patch communities) attached to the mines and coke ovens, the men worked long, difficult, and dangerous hours for very little pay. The women struggled to keep their families fed, clothed, and healthy in the face of highly adverse conditions. Together, they supported the United Mine Workers’ call for unionization that swept the area in the late 1800s and early 1900s and contributed to making Westmoreland County and southwestern Pennsylvania strongly pro-union for most of the 20th Century and, in some pockets, still today.

The 1920s witnessed a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, with an estimated four to six million Americans proudly identifying themselves as members of this White supremacist organization. A quarter-of-a-million Klan members lived and operated in Pennsylvania, and the southwest corner of the state saw more than its share of KKK organizing and actions.5 Catholic immigrants were a key Klan target. The Klan, like many Americans, defined the country as a White, Protestant nation and feared the growing Catholic population threatened the nation’s identity and their own power and position within it. Most of the immigrants spoke little to no English. They lived in semi-isolated, impoverished, ethnic, working-class communities surrounding the mines, coke ovens, and factories where they worked.

Voters in Pennsylvania cast their ballots for Republicans for the first third of the 20th Century, and Westmoreland was a reliable part of that trend. The Depression and Franklin Delano Roosevelt changed that. The mining and coke industries were the largest source of employment in the county in the 1920s. Yet, the glut of laborers meant that mining and coke families suffered under- or unemployment and declining wages even prior to the economic crash in 1929. By 1930, they were desperate. The New Deal Programs of the Roosevelt Administration altered the economic and political landscape in the area. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act gave workers the right to collective bargaining and the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration offered jobs and government funding. The Subsistence Homesteads Division established settlements that offered housing, work, and dignity to the jobless and their families, such as the community of Norvelt in Westmoreland County, named for EleaNOR RooseVELT.

As a result of the New Deal programs, people’s lives gradually improved and their voting patterns shifted. The Democratic Party welcomed Eastern and Southern Catholic Europeans into the party, thus beginning their assimilation into White America and obtaining their political loyalty for decades. In 1932 Westmoreland County voted Democrat in the presidential elections, according to records in the Westmoreland County Court House, and continued doing so until the 2000 George W. Bush vs. Al Gore election, albeit at a declining rate and with the exception of the 1972 election of Richard Nixon, who captured a majority of votes there.

Voting Democratic also meant belonging to or being supportive of the unions. However, the closure of industrial sites and the loss of union jobs inevitably led to a decline in union membership in the area, as it did across the United States. During the 1980s, the massive steel mills in Pittsburgh and the Monongahela River Valley shuttered. When the Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel plant in Monessen, Westmoreland County, closed in 1986, 800 people lost their jobs. The small town of Jeanette was the “Glass Capital of the World,” until its glass production factories closed in the 1980s. Another blow to organized labor came when the Volkswagen factory, which employed over 2,500 laborers, closed in 1988. The economic picture in Westmoreland County during the 1980s was bleak.

Westmoreland County commissioners responded with economic restructuring, creating the Westmoreland County Industrial Development Corporation (WCIDC), which recommended that banking on large industrial enterprises was futile, and the county should instead create industrial parks to attract smaller companies. Today 18 industrial parks dot the county and provide 9,000 nonunionized jobs.

Between 1990 and 2000 the economy improved. New sources of employment in information, health care, services, and education opened. The number of people working increased, more women entered the workforce, and salaries rose. As a result, the county became more prosperous and many household incomes increased by 44 percent. Nonetheless, 14 municipalities experienced growing poverty.

Westmoreland County was a predominantly White county in the 20th Century and remains one today. According to the 2010 census, 95.3 percent of the population is White, and in some small towns that figure rises to 99 percent, if not higher. At just 2.3 percent and 1.2 percent respectively, Black or self-identified mixed-race residents just make it into single digit figures, while Asians and Latinos each account for less than 1 percent of the population.

Westmoreland suffered a fate similar to most industrial centers in the United States. As factories and their ancillary industries shut down, union jobs and membership plunged, and workers who had found comradeship in their workplaces and union halls found themselves not just out of work, but no longer part of a group with a common identity, shared interests, and joint purpose. They also lost the affective community that had sustained them and their families for decades.

In its place, new types of jobs, in smaller, non-unionized workplaces, filled the void, as have the Protestant megachurches that now exist across the county and attract thousands to their religious services and social activities. The new jobs may pay better, the work may even be less difficult, but the esprit de corps that had bound the industrialized workers to each other, to their unions, to their community, and to the Democratic Party is gone, if not entirely for their generation, then almost completely for their children.

The Rise of the Republican Party

When I was growing up, I associated the Republican Party in Westmoreland County with the “old”—that is, wealthy—families in Greensburg: the country club set that golfed together, rode horses for sport, and attended the Golden Cup Steeplechase races at the Rolling Rock Club, on the Mellon estate in Ligonier. They belonged to the same bridge or ladies’ clubs, drove the most expensive cars, and lived in the big houses.

Mellon money has directly influenced political attitudes in Westmoreland County for the last half-a-century. In 1969 Richard Mellon Scaife, a major right-wing ideologue and financier of conservative think tanks and organizations, purchased the Greensburg Tribune-Review and other smaller papers in the area. He also launched the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review to counter the pro-Democratic Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Between 1992 and 2012, Mellon Scaife poured $312 million into the two papers, using them as a bully pulpit from which to relentlessly attack Democrats and any progressive program with which he disagreed. The incessant bombardment of reactionary propaganda contributed to the rightward shift that has occurred among broad swathes of the county’s population.

Mellon Scaife, who died in 2014, had direct, personal ties with Republicans in Westmoreland County, in part due to his connections with the Mellon Estate, Rolling Rock. As a result, he poured money into the Republican Party there. He told me that he helped finance the party’s infrastructure, paid for the party’s office, and purchased its first computer in the early 1990s.

Although upper-class elements and wealthy donors still populate the Republican Party, both the public face and voting base of the party have changed in the last 20 years. Today, a significant proportion of Republican Party officials are the children or grandchildren of coal workers. Paul Verostko grew up in a Democratic family. His father was a tool and dye worker, a solid union man, and an active member of the Democratic Party. He broke politically with his family, who remain loyal Democrats, to vote for Richard Nixon, “a brilliant candidate,” in 1972. He became active in the Republican Party in 2012 or 2013. Today, he leads one of the most active districts in Westmoreland County.

Elaine Gowaty, the former head of the Republican Party in Westmoreland and current head of the Westmoreland Federation of Republican Women, also embodies the political changes the children of working-class families have undergone. Her coal-miner father was a member of the United Mine Workers, and a loyal Democrat, as was the rest of her family. In 1980, she decided she liked Ronald Reagan, because, Gowaty asserts, he, along with the Republican Party, supported hard work, unlike the Democrats, who, she believes, support people who don’t work.

Gowaty, like so many Republicans, bought into Reagan’s fallacy about poor people, especially African Americans, and welfare. Reagan famously created and then denounced the mythical “Welfare Queen”: a Black woman from Chicago who drove a Cadillac and paid for her groceries with food stamps. Reagan and the Republican Party further proclaimed that the Democratic Party sponsors these programs for lazy chiselers, which hard-working White taxpayers end up funding. In fact, more Whites than African Americans, Latinos, or any other racial group receive welfare. Many of those who receive welfare work, usually in low-paying jobs with no benefits and/or live in a household with other people who are also employed. However, this calculated lie—that welfare recipients equals welfare cheats—persists because it plays well in many parts of the United States.

It resonates particularly well in Westmoreland County. The children and grandchildren of the immigrants who inhabit the county assert they, unlike the “welfare cheats,” inherited a strong work ethic from their parents and grandparents. Although many of their families benefitted from New Deal programs, they largely attribute their success to their own efforts. They were the “entitled poor,” as their current success proves, and they are determined to deny the benefits their parents and grandparents received to those who they consider the “undeserving poor.” Karen Kiefer, then treasurer (and current chair) of District 7 of the Republican Party in Westmoreland County, evoked this idea to explain White workers’ increased preference for Republicans. Newly-registered Republicans, as she wrote on the District 7 Facebook page, “said they joined the Republican party because it now represented the working man, whereas the Democrats represented those on welfare, the looters.”

Although few Democrats would accept that characterization of their party, there is one thing on which both they and Republicans agree. People in Westmoreland County are socially conservative, pro-gun rights and anti-abortion—policies that nearly all Republicans, but also many local Democrats, uphold. And many of them are openly racist. The 2008 presidential elections demonstrated the power of these positions, trends that the 2016 presidential elections confirmed and solidified.

John Boyle, a Democratic attorney born and raised in Westmoreland County, ran for Pennsylvania State Representative in 2008. During the primaries, he and his supporters knocked on the doors of loyal Democrats, asking for their vote. He remembers that many of his constituents asked him if he supported Hillary Clinton, or “that n****r.” Obama won the primaries nationally, but lost to Hillary Clinton in Westmoreland County. And in November 2008, John McCain received 57.8 percent of the county vote to Obama’s 41.1 percent. Many Democratic candidates, including John Boyle, also lost—due, many surmise, to their membership in the party that supported a Black man for president.

Outraged at the idea of a Black president, right-wing forces quickly mobilized against him. Among them was the Tea Party, which became particularly strong in Westmoreland County and exerted a huge influence on the Republican Party, pushing it further to the Right. Melinda Donnelly, a chiropractor, formed the Tea Party in Westmoreland County in 2009, along with her husband. They and other Tea Party activists organized large rallies three times a year in various county sites. By 2012 they had held 12 rallies and were going strong.

The Tea Party in Westmoreland County (TPWC) both reflected and accentuated conservative attitudes in the area. Donnelly told me that candidates sought the TPWC’s endorsement, which they needed to win an election. To obtain it, the candidate had to submit to an interview with the TPWC leadership and give the “correct” answers to a number of questions, including: “Do you believe there is such a thing as a moderate Muslim?” (No!) “Do you believe in traditional marriage?” (Yes!) “Would you support the building of a mosque in the city limits?” (No!) “When do you think life begins?” (At conception!) “Do you believe Mexico is a threat?” (Yes!)

When I asked Donnelly if she meant “illegal aliens” coming into the United States or Mexico itself, she replied, “Both!”

Photo: Michael Vadon via Flickr. // Political Research Associates

2016 Presidential Election

The depth and breadth of support for Donald Trump in Westmoreland County in the months leading up to the 2016 presidential elections was so visible and unmistakable that Rush Limbaugh made a point of commenting on it. He referred his listeners to Salena Zito’s Pittsburgh Tribune-Review article in which she describes the number of Trump signs in the small towns and rural areas of the county and the enthusiasm the people she interviewed expressed for Trump.

The wave of pro-Trump sentiment sweeping Westmoreland County was stoked by the enthusiasm, hard work, and determination of Republican Party activists. Paul Verostko remembers that the demand for Trump signs was so high he had a hard time getting enough of them. One of Westmoreland County’s most important events is its annual August county fair, a sprawling mixture of rides, agricultural displays and contests, exhibitions of products, food, and political booths. Verostko, who was in charge of the Republican Party booth, used the opportunity to distribute signs and literature and encourage attendees to help elect Trump.

Image courtesy of the author. // Political Research Associates

One local Republican designed a “Trump Mobile,” publishing flyers announcing the date, time, and location when the car would visit towns in Westmoreland and the adjoining Fayette County. The flyer encouraged supporters to “Get your picture taken with the Trump mobile, get Trump signs, hats, shirts, stickers, flags & buttons!” as part of the effort to “Make America Great Again!” Another ardent Trump advocate organized a skydiving “Jump for Trump” event. As she excitedly told me, “I jumped out of an airplane for Trump.” She and a group of like-minded friends, she explained, had “faith in him, we took a leap of faith.” (Their faith appears to have had some limits, however, since they all wore parachutes.)

Trump would win Westmoreland County by a landslide, obtaining nearly 63.5 percent of the vote.

A recent article in The New York Times challenges the idea that economic fears explain the large number of votes for Trump—across the country, and in places like Westmoreland County. Instead, it argues, Trump voters feared losing their social status. My interviews with Republicans in Westmoreland County both confirm and complicate this perspective. Rather than differentiating between the two, they reveal the close correlation between people’s perceived sense of economic and social standing.

Many Republicans transmuted their dread of what the Obama government programs would mean for the United States into a visceral horror of those groups they believed would benefit from and be empowered by these policies. Fear of the threatening “Other” permeates these Republicans’ political and emotional imaginations, as demonstrated by the questions the local Tea Party put to candidates seeking its support. For many Republicans in Westmoreland County, the frightful Other comes in the form of people of color: Black people, non-White immigrants, and Muslims, despite the fact, or perhaps precisely because, Westmoreland County is overwhelmingly White. Many Republicans in the county not only want to keep it that way, they want their region to serve as a model for the entire country.

A story Karen Kiefer told me exemplifies the perceived interrelation between status and economics. Kiefer recounted how, one day, several Latino men were working in her yard when she took them sandwiches and water. To her aggravation, they didn’t seem to know enough English to thank her. When she subsequently heard that her neighbor’s daughter had applied to the same landscaping company the men worked for but did not get the job, Kiefer said she felt so mad she vowed to go right down to the border and help build that wall. (Later, reflecting on her lack of construction skills, Kiefer said she decided she would make sandwiches for the wall builders instead.)

For Keifer, these Latino men had no right to be in the United States. Their failure to speak English or follow what she considered proper codes of behavior violated her definition of who belongs in this country and who does not. She was outraged because their very presence defiled her sense of what the United States is and should remain: a White nation inhabited by people who know the correct way to behave. In addition, she viewed these workers as threats to her neighbor’s daughter’s economic wellbeing, and, by extension, that of other deserving White people. Needless to say, it is unlikely that the neighbor’s daughter, like so many others who complain about immigrants taking their jobs, would accept the conditions or pay the men working in Kiefer’s yard did.

One issue that has confounded many is why so many women voted for Trump, despite his obvious misogyny and the accusations and evidence that he abused women. Penny Young Nance, president of Concerned Women for America, succinctly sums up their sentiments about Trump. “We weren’t looking for a husband. We were looking for a bodyguard.”

Their vote for Trump was driven by fear: of the non-White Other’s growing demographic and political strength; economic challenges; and the undermining of what they believe has been, is, and always should be a White, Christian nation. They elected Trump to protect what they consider their birthright from any and all domestic and international threats. To ensure this, they are willing to overlook his abuse of women, boorish language and attitudes, and unpresidential behavior.

The Republican women I spoke with in Westmoreland County echoed this perspective. Until recently, Robin Savage was chair of the county Republican Committee. She stepped down from that position in early 2018 to join Americans for Prosperity. As a Trump enthusiast, she opposes immigrants coming across the southern border. “They are just coming and no one does anything. Where are they going?” she asks. She also seeks for the country to once again rule the world, which is how she remembers things used to be. “I remember growing up and thinking America was the powerhouse and no one wanted to mess with us. We have lost our position as the world player and that bothers me.” Trump, she believes, will restore the United States’ leadership role in the world since, “You know what, this president is not going to bow down and apologize for anything in the past.” (How right she was! Speaking to the U.S. Naval Academy in May 2018, Trump announced, “They’ve forgotten that our ancestors trounced an empire, tamed a continent, and triumphed over the worst evils in history…We are not going to apologize for America. We are going to stand up for America.”)

I asked her if Trump represents her needs and interests as a woman, and her answer encapsulates why many women accept Trump. She is ready to overlook his scandalous behavior toward women because she agrees with his political stance of “making America great again” and his economic policies, which she believes favor people like her. (She and her husband own a business.) “I have to divide myself as a mother and as a woman. As a Mom, yes, he does [represent my needs and interests] because he is going after what I want. He will protect us, make the military stronger, build that wall, not let people scare us. As a woman, what he has said, he’s not a trained politician, some of the things that come out of his mouth.” Reflecting the internal division she referred to, Savage added, “As a female, do I like what he says, if he was my husband, would I smack him, yes.” Although Savage wouldn’t accept his behavior if she were married to him, she defends his treatment of women in general, particularly what she describes as his promotion of women in the business and political worlds. “Look at his cabinet,” she said, “he has a lot of women.” She further considers him a successful and non-sexist businessman. He has “a lot of overachieving women [who have worked for him], he’s given them opportunities. It’s not like he has all men in the business.”

Tricia Cunningham, the woman who organized the Jump for Trump—and who boasts that neither she nor any of her children has ever received any economic assistance from the government because “they work their butts off”—echoes Savage’s beliefs. “Trump has put more women in superior positions in politics and business than anyone. He chooses talent.” Cunningham also feels a deep, personal loyalty for Trump, who she claims to have met at a luncheon in his hotel in Atlantic City 23 years ago. “I would take a bullet for that man, for anyone in his family, and for the grandchildren.”

The 2018 special election

In March 2018, a special election was held in the 18th district of Pennsylvania. The seat had been held by Republican Tim Murphy, who was forced to resign when news broke that he had encouraged a woman he was carrying on an extramarital affair with to have an abortion. Trump (who had swept the district with a 20-point lead over Clinton in 2016) pulled out a number of stops to ensure the victory of Republican Rick Saccone, who had proclaimed he was “Trump before Trump was Trump,” over Democrat Conor Lamb. He visited the area to rally the troops, as did several members of his administration and his son Donald Trump, Jr. He even announced a tariff on steel and aluminum imports to win over or retain the votes of workers in the region. But Lamb ended up winning with a few hundred votes more than Saccone, confounding the Republicans who saw the region as a lock.

But though he won overall, Lamb still had lost Westmoreland County, where Saccone garnered 57 percent of the vote—a smaller percentage of the votes than Trump had, but still a strong majority. Shortly after the election, I spoke with Paul Verostko and Mike Ward, whose mother, Kim Ward, is the Republican State Senator from the district. They remarked that Saccone was anti-union, a stance they disagreed with, and had Kim Ward run, they were certain she would have won. Ward had previously told the press, “My mother was the most qualified candidate. She was the most prepared and, as a female candidate in this climate, that’s an add-on, too.” He went on to say, “Rick is a friend and I don’t want to beat up on him...but if you didn’t have four party bosses picking your candidate and the people were able to vote, he never would have run.” What’s important to note here is that both men come from traditionally pro-union families, as is true of much of the Republican Party leadership in Westmoreland County, and far from abandoning that position, they believe it’s still essential to Republicans’ success, there and elsewhere. The irony, of course, is they both support a pro-corporate, anti-worker president whose program includes the elimination of working people’s rights and the upward redistribution of wealth.

Going Home

In 2008 I attended a meeting of the Norvelt Historical Society to plan the New Deal community’s 75th anniversary. I was writing a book on Norvelt, along with two local historians. Since the participants loved the Roosevelts, particularly Eleanor, and partially attributed their parents’ and grandparents’ success to the New Deal, I suggested we invite Michelle Obama to attend the upcoming celebration. The response was dead silence, broken only when someone suggested other people to invite. It was only later, in talking with one of my coauthors who also attended the meeting, that I realized the majority of people in Norvelt, like those in the rest of Westmoreland County, had not voted for Obama but for McCain.

The realization piqued my curiosity: when had my home county changed its longstanding political affiliation? It was a transformation I hadn’t been aware of, since I haven’t lived in the area since leaving for college at 17. To explain the generational shifts in party affiliation, I can point to the economic transformation of the county, the closing of industry and the mines, the demise of the unions, and their replacement with new affective communities such as the megachurches, to partially explain this political transformation. But when it comes right down to it, I believe the most significant factors are White supremacy and conservative social values, which many in the area equate with being American and what they will fight to preserve or reinstate. As a girl growing up in Westmoreland County to a Republican mother, those are the values I was taught, and they are the ones I see being brandished by a dismayingly large number of people in the area.

But a key question remains unanswered: can they change? I don’t know. I do know that I did, and that I did because I was challenged to learn about other people’s lives and realities. I think that is our challenge: determining how to cultivate an awareness of and identification with people of radically different racial, sexual, and national groups. So that instead of seeing the “Other” as a threat, people like those I grew up with can see them as a resource to work alongside to build a better and safer world.

[Margaret Power is a professor of history at Illinois Tech. She has published on the Right in Latin America and the United States. Her current work focuses on the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

1. Paul Verostko, phone conversation with author, October 9, 2017.

2. Leslie Baum Rossi, Facebook post, May 28, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10209339945033460.

3. Paul Verostko, interview with author, March 23, 2018.

4. Official Election Results for Westmoreland County General Election, November 8, 2016, https://www.co.westmoreland.pa.us/DocumentCenter/View/10280/2016-General-Election-Candidate.

5. Philip Jenkins, Hoods and Shirts: The Extreme Right in Pennsylvania, 1925-1950 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997) p. 66.

6. Joe Sisley, WCDIC Marketing Director, interview with author, May 9, 2018.

7. Westmoreland County Comprehensive Plan, January 2005, https://www.co.westmoreland.pa.us/654/Comprehensive-Plan, p. 76.

8. Karen Kiefer, comment on Westmoreland County Republican Party District 7’s Facebook page, September 15, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/WCRCDistrict7/posts/1430729030296469.

9. John Boyle, interview with author, March 10, 2011.

10. Melinda Donnelly, interview with author, November 10, 2011.

11. Leaflet sent to the author by Paul Verostko.

12. Tricia Cunningham, phone interview with author, March 18, 2018.

13. Niraj Chokshi. “Trump Voters Driven by Fear of Losing Status, Not Economic Anxiety, Study Finds,” The New York Times, April 24, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/24/us/politics/trump-economic-anxiety.html.

14. Karen Kiefer, phone interview with the author, October 9, 2017.

15. Jeremy W. Peters and Elizabeth Dias, “Shrugging Off Trump Scandals, Evangelicals Look to Rescue G.O.P.,” The New York Times, April 24, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/24/us/politics/trump-evangelicals-midterm-elections.html.

16. Robin Savage, interview with author, March 28, 2018.

17. The number of women in Trump’s cabinet is actually fewer than in Obama’s and similar to previous Republican administrations. Jasmine C. Lee, “Trump’s Cabinet So Far Is More White and Male Than Any First Cabinet Since Reagan’s,” The New York Times, March 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/13/us/politics/trump-cabinet-women-minorities.html.

18. Robin Savage, interview with author, March 28, 2018.

19. Mike Ward and Paul Verostko, interview with the author, March 23, 2018.

20. Ryan Briggs, “Saccone’s poor showing in PA-18 spurs Republican finger-pointing,” City & State Pennsylvania, March 14, 2018, https://www.cityandstatepa.com/content/saccones-poor-showing-pa-18-spurs-republican-finger-pointing.