How Unions Can Solve the Housing Crisis

Dr. James Peter Warbasse in the journal Co-operation, “Once the people of New York City lived in their own houses, but those days have gone. ... The houses are owned by landlords who conduct them, not for the purpose of domiciling the people in health and comfort, but for the single purpose of making money out of tenants.” That was in 1919.

A century later, things have gone from bad to worse. A quarter of U.S. households pay more than half their income in rent. In New York City, homelessness has hit record levels.

Today, more than 100,000 New Yorkers live in apartments built by the labor movement between 1926 and 1974, mostly through an organization called the United Housing Foundation. Roughly 40,000 still-affordable cooperative housing units—Amalgamated Houses, Concourse Village and Co-op City in the Bronx; Penn South in the heart of Manhattan; 1199 Plaza in East Harlem; Rochdale Village and Electchester in Queens; Amalgamated Warbasse in Brooklyn—stand as monuments to what an organized working class can achieve. This housing provides a bulwark against gentrification and a blueprint for ending the housing crisis. Let’s look at how it all got started, how it came to an end and what it would take for labor to build again.

Source: Kheel Center, United Housing Foundation // In These Times

Radical beginnings

The story begins in 1916 in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, where immigrant workers from Finland found themselves overcharged for subpar housing. Members of the Brooklyn Finnish Socialist Club figured out they could build higher quality housing for less than it would cost to rent from a landlord. Sixteen families came together to form the Finnish Home Building Association. Their first construction project was financed by equity contributions of $500 each from six families, “comrade loans” totaling $12,000 from neighborhood residents and a $25,000 bank loan.

The first building, named Alku (Finnish for “beginning”), was completed that year. Within a decade, there were almost 30 Finnish-owned co-op buildings in Sunset Park, with carrying costs (a monthly maintenance fee paid by each household) around half the rent of similar apartments in privately owned buildings. Members were forbidden from selling their units at a profit to ensure lasting affordability. In a pattern that would be repeated for decades to come, the housing co-ops became part of a local co-op ecosystem that included a restaurant, bakery and grocery store.

This model of affordable housing cooperative was so new that state law had no legal classification for it until the 1920s. Alku soon inspired a wave of limited-equity cooperative development by other radical worker organizations.

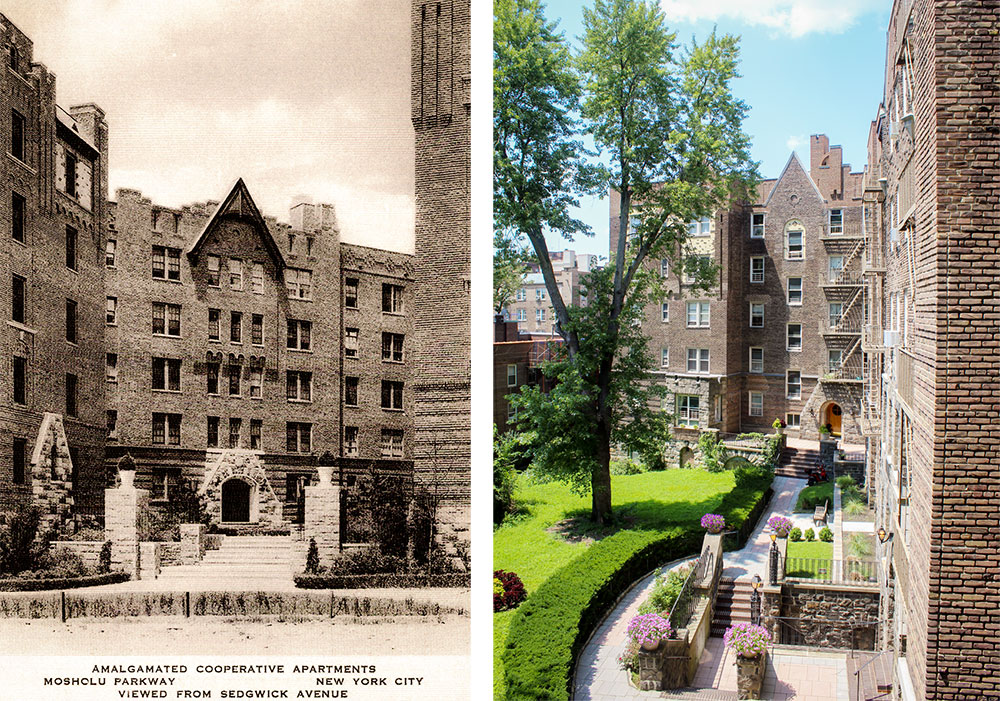

In 1925, a Yiddish Communist group called United Workers began planning a housing cooperative in the Bronx. They raised money through bond sales advertised in the radical Yiddish daily Morgen Freiheit (“Freedom Tomorrow”) and were able to buy an empty tract of land next to Bronx Park. Tenants were recruited from the general public. The United Workers Cooperative Colony, known as “The Coops” (rhymes with “soups”), opened in 1927 and rapidly added a second building for a total of 2,000 residents. The neo-Tudor garden apartment building, encircling a central courtyard, was an escape from the suffocating windowlessness of Lower East Side tenements—and it was affordable. It was as much a political project as an economic one, with a 20,000-volume library, regular cultural and political programming, and involvement in the broader community through a network of co-op businesses, political support for local tenants and workers, and attempts at racial integration.

The Coops inspired other Jewish left organizations to launch similar projects, turning the Bronx into a hub for experiments in working class cooperative housing. The Arbeiter Ring (Workmen’s Circle) launched Shalom Aleichem houses across the park, followed by the Farband Houses, built by the Yidisher Natsyonaler Arbeter Farband (Jewish National Workers Alliance). And soon, a more powerful backer would help the co-op movement scale up across the city: labor unions.

Images via Amalgamated Housing Cooperative / Ed Yaker (L) and Erik Forman (R) // In These Times

House of labor

The bulk of the 40,000+ units of limited-equity cooperative housing sponsored by the labor movement in New York City originated with an immigrant garment worker-turned-union organizer named Abraham Kazan.

Kazan was a true believer. In the 1960s, after he had completed tens of thousands of units of housing, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller told him in passing he would have done well if he had gone into business. Kazan replied, “I am a cooperator, interested only in building the cooperative commonwealth.”

credit: In These Times

Kazan immigrated to the United States in 1904 at age 15 to escape anti-Semitism in the Ukraine, and was influenced by anarchist ideas and a stint on a proto-Kibbutz in New Jersey. After helping organize a small strike at his job as a garment worker, he eventually went on staff with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and later the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. As a union staffer, he began promoting cooperatives. His first successful project was a consumer co-op business that provided 7,000 union members with sugar and matzo during World War I. He soon began dreaming of building housing.

Gathering rank-and-file garment workers and a handful of low-level union staffers, Kazan incorporated the group as “ACW Corporation,” using the union’s initials “to give the impression we had a Big Brother behind us in this effort”—though they lacked the union’s formal backing.

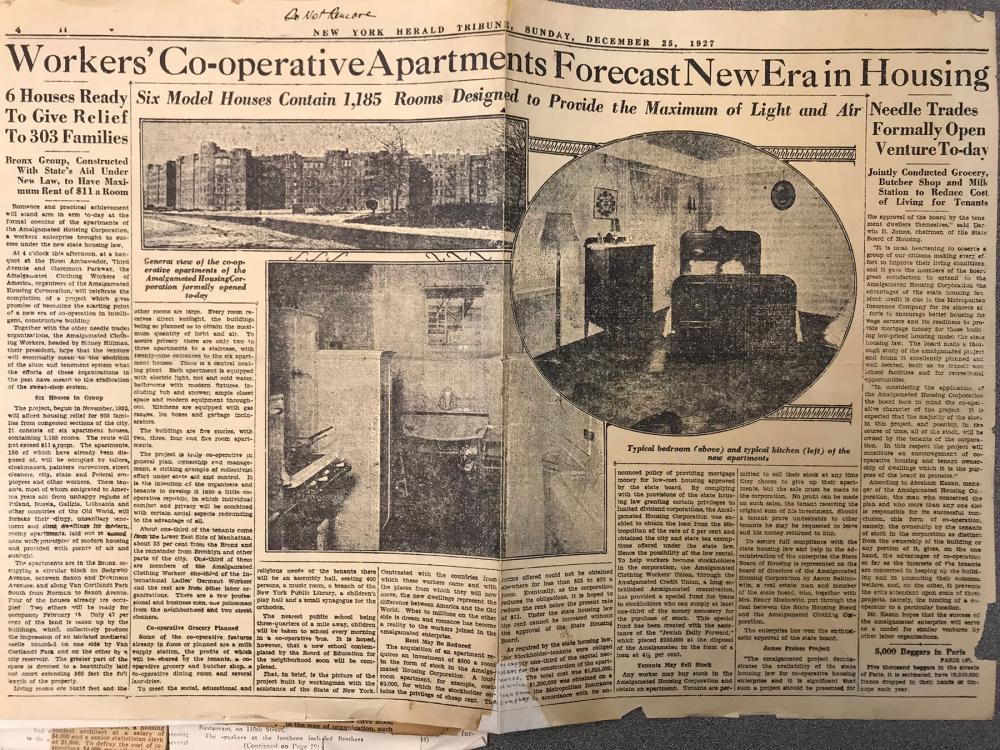

It took the possibility of government support for Amalgamated to throw its weight behind co-operative housing. In 1926 New York state passed the Limited Dividend Housing Companies Law, granting condemnation rights and local tax abatements to housing companies that limited profits and restricted rents to affordable levels.

The ACW Corporation drew up plans to develop a 303-unit cooperative in the Bronx. It sold shares to future residents at $500 each (about three months’ pay for a union worker). The union-owned Amalgamated Bank agreed to loan each resident up to 50 percent of the cost of their equity stake, and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company provided a $1.2 million mortgage. The Jewish Daily Forward also helped secure financing and provided short-term loans to cover cost overruns.

Ground was broken Thanksgiving Day 1926, and the first residents moved in the following November. By early 1928, the Amalgamated Houses were fully occupied. The cooperators (as co-op residents were called) soon launched a cooperative grocery store, milk delivery service and even a bus service to bring workers to the subway. In the decades that followed, the housing cooperative grew to around 1,500 units. The Great Depression wiped out many New York City cooperatives, but Amalgamated cooperators’ willingness to help support their neighbors—combined with cagey negotiations with creditors—helped them survive the Great Depression. Kazan’s model worked.

Soon more unions followed.In 1949, IBEW Local 3 President Harry Van Arsdale Jr. began planning a cooperative housing development called Electchester in Queens. Union members provided the labor, some paid and some volunteer. Over 17 years, Electchester expanded to 38 buildings with around 2,500 units of housing. Van Arsdale himself lived there. It became a social and cultural hub for the Local, with a bowling alley, auditorium, movie theater, cocktail bar, coffee shop, shopping center, library and a host of clubs and social organizations.

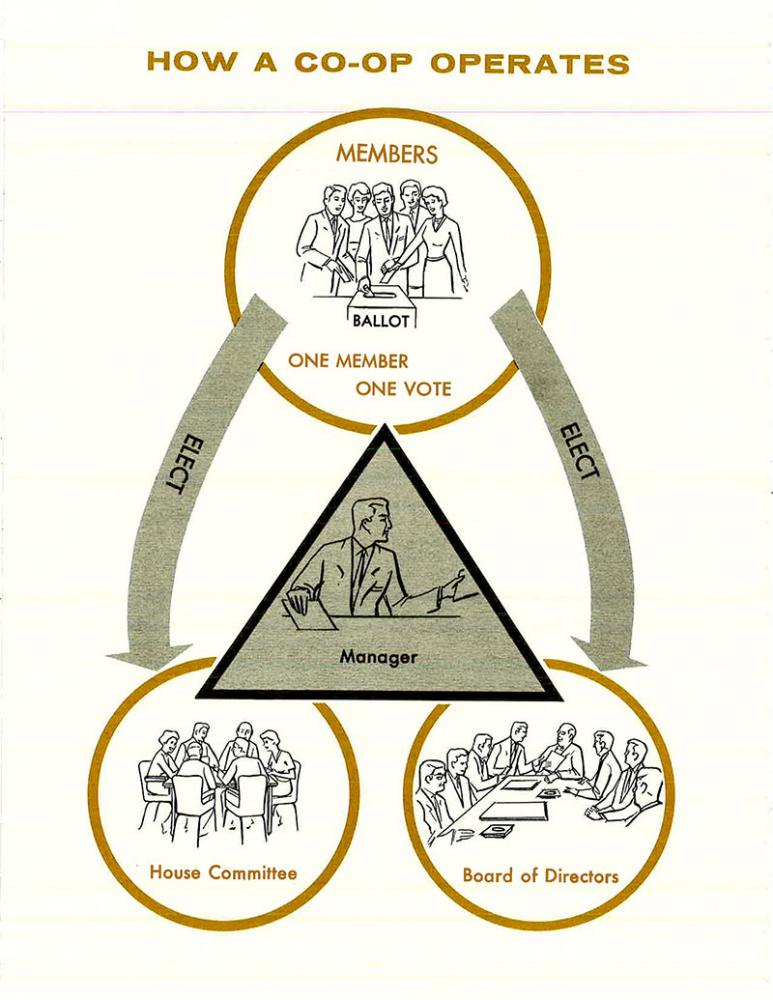

To popularize cooperative development with other unions and carry out projects on a larger scale, Kazan created the United Housing Foundation (UHF) in 1951, a coalition of organizations and individuals that included 19 unions. UHF was to be funded by a modest 1 percent fee on the cost of building each development. To carry out the actual construction work, Kazan created a second organization to act as general contractor, Community Services Inc., which built the housing and provided technical assistance.

The housing units were open to any worker, union or not, so long as they were below a limit on income. Applicants had to show up and wait in line on the day applications were accepted.

As the postwar era progressed, the stars would align for an unprecedented expansion of labor’s cooperatives, boosted by mainstream political support. But the patronage of New York City’s political class came with strings attached.

Home front

“We have wiped out the sweatshop; we return to wipe out the slum,” intoned ILGWU President David Dubinsky at the groundbreaking ceremony of the East River Houses in 1953, funded in part by his union. The brand-new red- brick towers loomed above the dilapidated low-rise tenements of the Lower East Side. This was where the parents and grandparents of so many New York City unionists had toiled doing garment work. Dubinsky’s generation saw it as their duty to eradicate exploitation from the blocks where they grew up.

In returning to wipe out the slum, these prodigal sons found unlikely allies in New York’s ruling class. Slum clearance policies made land available, and in 1955, labor helped pass the Limited-Profit Housing Companies Act, better known as the Mitchell-Lama program. It provided low-interest mortgages and tax abatements for limited- equity cooperatives and affordable rentals. Over 100,000 units of housing would be built under the program. More than half were cooperatives, the majority of which were built by Kazan’s UHF.

Political support was forthcoming in part because labor’s cooperatives fit within the “urban renewal” paradigm charted out by men like Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. In the postwar era, political elites across the U.S. reconfigured cities to force new patterns of mass consumption (car and home ownership) and racial segregation. The federal government provided guarantees for home loans to whites, facilitating white flight. Awash with federal subsidies and tax breaks, Moses and others used their powers under “slum clearance” laws to bulldoze neighborhoods to build highways and high-rise housing. They created a racialized hierarchy of urban housing: public housing for the poor (mostly people of color), cooperative housing for middle-income workers (mostly white), and private-market luxury for the white ruling class.

UHF partnered with Moses on two projects that resulted in displacement of slum residents: Cooperative Village on the Lower East Side and Penn South in Midtown Manhattan. At Cooperative Village, UHF took steps to mitigate displacement by giving priority to the neighborhood’s original residents. At East River Houses, part of Cooperative village, 974 of 1,672 units were filled with people from Lower East Side slums. But critics observed that the cost of co-ops was out of reach for many who lived in the neighborhoods and that the planning process had excluded them. UHF resolved to stop building on slum clearance sites.

Perhaps seeking to redeem themselves, in the early 1960s Moses and UHF set out to create the largest racially integrated community in the world. Rochdale Village, located in the middle of the large black community of Jamaica, Queens, was to be built without displacement. Tellingly, UHF worried it would not be able to attract enough whites to live in a majority black neighborhood—apparently without asking how Jamaica’s predominately black residents would feel.

But, most likely because the base of the co-op movement was mostly white, it was far more challenging to recruit people of color. The original residents of Rochdale Village were about 85 percent white (predominantly Jewish) and 15 percent black. Despite the uneven mix, it was celebrated in 1966 as a rare model of racial integration. But success was short-lived.

Image via Kheel Center, United Housing Foundation // In These Times

Racial tensions flared in 1968, when black power activists on the local school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville attempted to replace members of the majority-Jewish United Federation of Teachers (UFT) with teachers selected to advance an Afro-centric curriculum. The UFT launched a city-wide strike and the conflict got ugly, rending the alliance between African Americans and Jews that had figured heavily in the civil rights movement. Within a few years, the Jewish majority moved out, and the co-op became a majority black institution, as it remains today.

By the mid-1960s, with a mix of union pension funds, state funding and equity contributions from workers, UHF had built tens of thousands of units of high-quality housing, permanently changing the city skyline. But the movement had enemies.

Fred Trump, Donald Trump’s father, was worried that the low-cost, high-quality developments that UHF built would undercut the high rents he was charging as a landlord, and wanted state subsidies for his own projects. He pulled strings and greased palms to prevent the City Planning Commission from granting UHF a site on Coney Island for the Amalgamated Warbasse development. Trump succeeded in getting the UHF site cut in half and took the half closer to the beach for himself. It was a harbinger of things to come.

Photo courtesy of CountMeInNYC // In These Times

Co-op City vs. Trump City

Even as competition from private developers intensified, UHF remained the go-to entity for large-scale cooperative housing. The organization had developed such a strong reputation that Gov. Nelson Rockefeller was lobbying it to build on the gigantic site of the defunct Freedom-land amusement park in the Northeast Bronx.

In 1965, UHF and Rockefeller unveiled a plan to build the largest housing cooperative in history: 15,382 units in 35 high-rises and 236 town houses, all union-built. The projected cost of “Co-op City” was $259 million, financed through a $32 million investment through sales of shares ($450 per room) to cooperative residents, with the balance financed by a low-interest loan under Mitchell-Lama. In 1965, UHF projected that carrying charges would come to about $25 per room per month.

By 1968, the first buildings were complete and families began to move in. As one resident reminisced, “We thought this was Shangri-La.”

Photo by Erik Forman // In These Times

But the ground was shifting beneath their feet—literally and figuratively. Construction was delayed when the marshy site began to settle. Massive inflation and rising interest rates began increasing construction costs. By completion in 1972, the total cost overran by around $80 million and monthly charges were at $31 per room.

The residents fought the increase, and filed a federal lawsuit against UHF in 1972 claiming securities fraud. As the case slowly wound its way through the courts, the cooperators resorted to more radical tactics. In 1975, with carrying charges hitting $53, they launched the largest rent strike in history. Over 12,000 Co-op City households participated, withholding millions of dollars in carrying charges, collecting the checks in garbage bags. Seeking to extricate itself from the quagmire, UHF passed the development over to the state. The state postponed carrying charge increases after 13 months of strike, and eventually provided support.

Co-op City remains one of the most affordable places to live in New York City, but the rent strike all but destroyed UHF. Kazan had passed away in 1971, leaving UHF without the visionary leadership that had guided it from the start. And the city was becoming more hostile to working-class interests.

Since World War II, New York City’s labor movement had won something approaching social democracy at a municipal level. The city government sponsored a miniature welfare state, complete with free higher education at the City University of New York, an affordable and functional subway system, controlled rents and more. But as deindustrialization and white flight hollowed out the city’s tax base, the municipal government turned to the private bond market and the federal government to cover a mounting deficit. This assistance gave an opening for enemies of labor on Wall Street and in the federal government to attack.

In 1975, Wall Street orchestrated a capital strike, blocking the city’s access to bond markets and forcing it to hand over control of its budget to an Emergency Financial Control Board made up of corporate and banking elites. Implementing a “shock treatment” of austerity that echoed policies of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, the board imposed tuition at the City University of New York, laid off thousands of public servants, hiked the subway fare and attempted to do away with rent control.

Under this dictatorship of capital, backing loans to the labor movement for cooperative development was out of the question. The role of government would now be to woo the global rich with tax cuts and luxury developments. Emblematic of this shift, even as Co-op City was fighting for state support, the city granted a young Donald Trump an unprecedented 40-year tax abatement to turn the Commodore Hotel into a Hyatt. As historian Joshua Freeman put it, New York City was now Trump City.

Photo by Erik Forman // In These Times

To build again

The ensuing decades saw more of the same, and today a new addition to Trump City is under construction: Hudson Yards, a luxury development meant to create investment properties for the global rich. Its towers stand in stark contrast to the nearby Penn South, union-built with city support so that garment workers could walk to work. Hudson Yards has received a 19-year tax abatement and is being funded in part by up to $3 billion in city-issued bonds. If the development is not profitable, the city has agreed to pay the interest to bondholders out of tax revenue. In other words, while the city fails to guarantee housing for the working class, it guarantees profits for the ultra-rich.

Predictably, the developers are seeking to build as much as possible with nonunion labor, provoking a showdown with New York City’s building trades. Tagged as the #CountMeIn movement, a drumbeat of job actions is intensifying at Hudson Yards, with weekly pickets and the beginnings of a guerrilla war of walkouts and slowdowns. Sadly, the trades are divided. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters invested in the construction of one of the luxury towers, and the union does not support the protests—though increasingly rank-and-file carpenters are joining the movement.

There is deep irony in union funds building nonunion housing that most workers will be unable to afford. Labor is quite literally investing in its own destruction.

It doesn’t need to be this way. Most of the necessary conditions for unions to develop housing are in place. The city is seeking affordable housing developers for parcels of land across the boroughs. Financing is available through Low Income Housing Tax Credits and union pension funds invested in the AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust. And the state still grants tax abatements for affordable housing developments.

The 40,000 units of housing built by UHF are the embers of a vision that once fired the labor movement: Build for human need, not for profit. The working class needs housing now more than ever. Labor can build it again.

[Erik Forman has been active in the labor movement for over a decade as a rank-and-file organizer, at the forefront of campaigns to unionize the U.S. fast food industry. He currently works as a labor educator in New York City and is pursuing a Ph.D. in cultural anthropology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York..]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Reprinted with permission from In These Times. All rights reserved. Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate.

Never has independent journalism mattered more. Help hold power to account: Subscribe to In These Times magazine, or make a tax-deductible donation to fund this reporting.