Women in Prison Punished More Harshly than Men Around the Country

This investigation is a collaboration between The Chicago Reporter, NPR News Investigations, and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

During her twenty years in an Illinois prison, Monica Cosby received disciplinary tickets and was sent to solitary confinement more times than she can remember. And she wasn’t alone.

“You’ll get a ticket or get sent to seg [solitary confinement] for having… a piece of candy,” she said. “Or you have a library book that’s overdue — and you’re on your way to the library.”

Sometimes, Cosby got in trouble for breaking rules that she thought she was following — like the time she picked up an extra shift working in the kitchen. Cosby says she got permission, but a correctional officer still issued her a ticket for unauthorized movement and put her in solitary for 60 days.

More often, Cosby says she was punished not for things she did, but for things she said — like the time she got in trouble while quietly playing Scrabble by herself. When a correctional officer asked her what she was doing, she gave him attitude. “What does it look like I’m doing?” she replied.

And so, although she had permission to have the Scrabble board, he issued her two tickets: one for “contraband” and one for “insolence.”

“Out of 20 years of me locked up, I think there’s only like three people that I know that never got a ticket for insolence,” she said.

The Illinois Department of Corrections denied our request for Cosby’s disciplinary records, citing an Illinois law.

But an investigation by The Chicago Reporter, the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University and NPR has found that women in Illinois — and in prisons across the country — are disciplined at significantly higher rates than male inmates for mostly minor, subjective infractions. We analyzed data from fifteen states that track discipline by gender, visited four different prison systems, and interviewed dozens of current and formerly incarcerated women, academics, and prison staff. We determined that although female inmates are less likely than their male counterparts to act out violently in prison, they receive more disciplinary tickets for minor offenses — matters that are unlikely to compromise safety.

Experts say that this disparity stems in part from women’s attempts to cope with the lingering effects of trauma in an environment that exacerbates it.

Though women comprise less than 10 percent of all prison inmates, their numbers have grown eight-fold over the past 40 years. In an effort to better manage this population, and as part of a movement known as “gender-responsive” corrections, officials have slowly begun to adjust their needs assessments, case management protocols, and substance abuse treatments.

However, most if not all of those efforts have yet to change the stark disparity in how women behind bars are disciplined. The effects of these disparities have far-reaching and enduring effects on families and communities: women are often primary caregivers, and many are also primary breadwinners. More than half of imprisoned women across the country are mothers.

To better understand this problem in Illinois and nationally, The Chicago Reporter and NPR filed Freedom of Information Act requests for disciplinary data with 26 state correctional agencies. Eleven states either charged high fees for the data or said they don’t keep it. But almost all of the fifteen states that supplied data from 2016 and 2017 revealed the same pattern: women in U.S. prisons are being disciplined at higher rates than men, sometimes exponentially so, for lower-level offenses.

According to our analysis, in Vermont, female inmates were more than three times as likely to receive a ticket for “making a derogatory comment.” In California, women were more than twice as likely to be ticketed for “disrespect without potential for violence.” In Rhode Island, women were more than three times as likely to receive tickets for “disobedience” and 7 times as likely to receive tickets for a “disturbance.” And in Indiana, women’s rates of discipline were more than twice as high as men’s overall, and almost three times as high for refusing to obey an order. Women in Indiana were also nine times as likely to receive tickets for being a “habitual rule violator.”

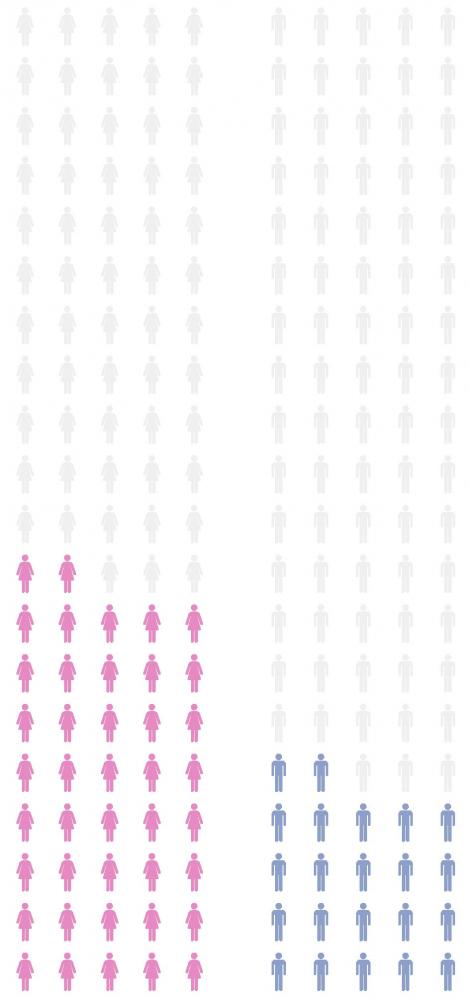

With more than 42 insolence infractions for every 100 inmates, women in Illinois prisons are cited at a rate nearly twice as high as their male counterparts (22 per 100). Insolence is the most common infraction in Illinois women’s prisons, accounting for nearly one out of every five disciplinary cases. This graphic depicts the average rate of insolence infractions per 100 inmates by gender.

Source: Women’s Justice Institute, Illinois Department of Corrections

Our analysis also revealed that the punishment meted out for these low-level infractions are often more harsh for female inmates. Women in Rhode Island prisons were more than three times as likely to be placed in restrictive housing for “disobedience.” In Idaho prisons, although men are more likely to assault both staff and inmates, women are more likely to be put in physical restraints. And in California, women were more likely to have their phone privileges revoked, a punishment that not only affects a woman, but her children.

In many states, infractions are also punished by revoking “good conduct credit” that would shorten an inmate’s sentence, causing them to serve more time. In California, between 2016 and 2018, women inmates had almost a day per week on average of good conduct credit revoked, a higher rate than their male counterparts. In Illinois, women lost a total of 93 years through good credit revocation in 2015 alone. The Illinois Department of Corrections did not provide data on male inmates, but data on female inmates obtained through a FOIA request showed some of the incidents that resulted in the revocations for female inmates: 90 days for grabbing a staffer’s arm, 60 days for refusing to change cells or cellmates, 30 days for making a threat.

Maggie Burke, former warden of Illinois’ largest female prison, said that prisons fail women. Officers write “emotional tickets,” she said, based on their “anger and frustration” with the inmates.

“I would say as a whole, we discipline based on emotion rather than on safety and security,” said Burke, who spent 29 years in corrections. “Is a facility safer because I put a woman in seg longer because she talked back to someone? There is a power struggle going on and… we have not prepared our staff to manage this population.”

An Affront to Gender Norms

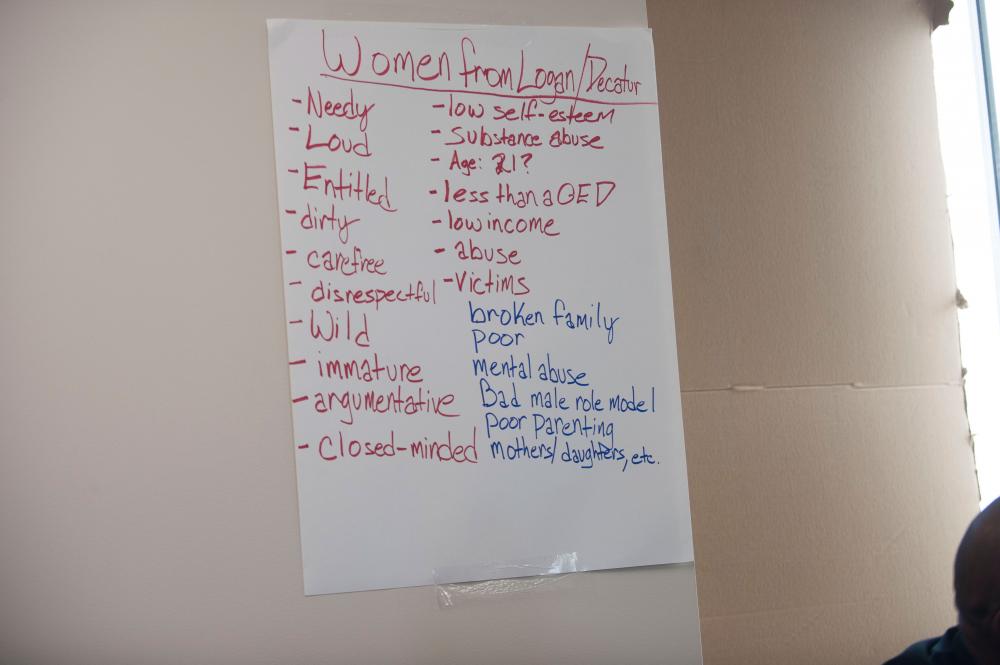

PHOTO BY BILL HEALY

A sheet lists biases that correctional officers have towards female inmates going into a training for correctional officers at Logan Correctional Center on March 15, 2018.

Criminality among women has long been seen as a particular affront to social order. While male outlaws in popular culture are often romanticized, women are instead met with contempt.

“There’s a boys will be boys sentimentality,” said former inmate Monica Cosby. “But we judge women harsher. It’s like, ‘What kind of woman are you? What kind of mother are you?’”

These attitudes have long been documented in prison records. As far back as 1845 prison administrators in Illinois considered female inmates more disruptive and difficult to manage, according to research by L. Mara Dodge, a professor at Westfield State University in Massachusetts.

Dodge also analyzed inmate records from the State Reformatory for Women in Dwight, Illinois, from 1954 to 1967. She found that the top three rule violations among female inmates were talking loudly, disrespect to staff, and lateness. Women were also disciplined for “language unbecoming a lady,” hanging wet towels in the wrong place, and eating too much or too little (one ticket was issued for “failure to eat all of her French toast”).

This over-policing was unique to women, Dodge concluded. At the time, the Illinois prison for men at Stateville was notorious for its strict rules, but “although such actions as ‘having top button of shirt unbuttoned’ were prohibited at both institutions,” Dodge wrote, “men were disciplined for only the most serious violations.”

“In prison as in the free world women were, and are, expected to acquiesce to a level of social control that would be deemed unacceptable by men,” she concluded.

In the 1980s, Texas A&M University professor Dorothy McClellan examined disciplinary practices at men’s and women’s prisons in Texas and found what she called “two distinct institutional forms of surveillance and control.” Women received far more disciplinary tickets than men, mostly for low-level, non-violent offenses.

Women were also more likely than men to be severely punished for these infractions, McClellan found, including more time in solitary confinement and harsher restrictions during family visits. Unlike male inmates, if women had received a ticket for any infraction in the past month, they would be denied their bimonthly, five-minute call home or be limited to no-contact visits with their children.

The 1990s saw an increased interest in female inmates, and researchers determined that their pathways into criminal behavior overwhelmingly involved poverty, abuse, and trauma. In 2003, the National Institute of Corrections published a compendium of that research, establishing national best practices for gender-responsive prisons that “reflects an understanding of the realities of women’s lives and addresses the issues of the participants…. [and includes] a strength-based approach to treatment and skill building.”

Click here for related article: talking back or talking it through

Since that time, a handful of states — including Illinois, Michigan, Iowa, California and Vermont — have instituted reforms. They have adjusted their intake processes and risk assessments. They have hired more women in a field still dominated by men, and promoted more of them to leadership positions.

But the data shows they have not made significant strides in changing the way that discipline is meted out in women’s facilities — a challenge that experts say is crucial to avoid retraumatization and help women succeed once they are released.

“Women are being harmed by incarceration. We know that,” said Alyssa Benedict, a national expert in trauma-informed care and gender-responsive corrections and the director of CORE Associates, a consulting and training firm. “What we need to acknowledge and address is that discipline systems in women’s prisons are multiplying these harms.”

“There are prisons around the country that are doing some good work and making some really important strides, but we have a long way to go.”

Understanding the damage done by abuse

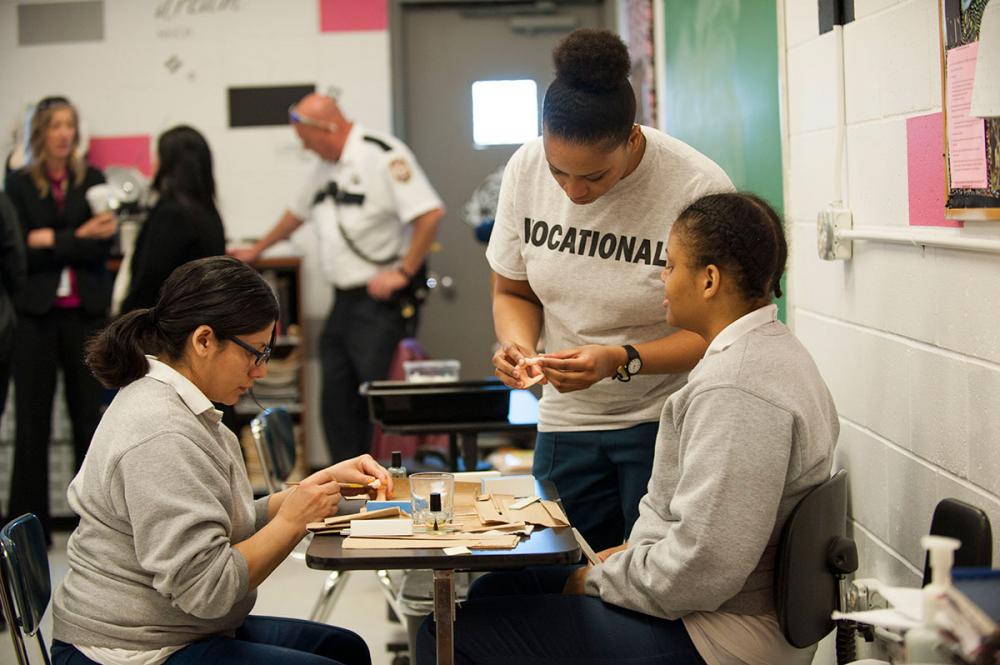

Photo by Bill Healy

Women at Logan Correctional Center had access to only one vocational program, nail technician training, last March. Twelve out of about 1,750 inmates were enrolled in the program.

Female prison populations across the country have in common high rates of past physical and sexual abuse.

A 2010 study by Illinois found that 98 percent of women behind bars in the state had experienced physical abuse before incarceration, and 75 percent had been victims of sexual abuse. Recent research found that between 61 and 83 percent of incarcerated women in Illinois exhibit symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. That is three times more than incarcerated men. It is also higher than any other studied demographic, including combat veterans. These figures mirror studies in other states and in the federal prison system.

Advocates like Benedict say the growing body of research on trauma ought to be tapped to help develop correctional systems that allow incarcerated women to rehabilitate and recover. Instead, many common aspects of prison life — including strip-searches, verbal abuse, restraints, and isolation — exacerbate trauma’s lingering effects.

“Staff have been taught to use these highly ineffective and punitive tools of the prison trade to inappropriately label, control and punish women’s behavior instead of understanding and working with them to determine and implement solutions,” said Benedict. “[These situations are] contrary to everything we know in psychology and are actually causing problems, harming women and creating unsafe facilities.”

For example, research on trauma has found that, in order to work through PTSD, survivors need to experience safety and consistency. But traditional prison environments are wholly unpredictable, interrupted at any time by spontaneous lockdowns, shakedowns, and strip searches.

“If you have them storming in your room, and that’s like the only space you have, and that’s constantly invaded and looked through…It hurts you mentally and emotionally, so much that it actually causes physical pain,” said Monica Cosby, who was released in 2015.

Click here for related article: Changing the environment to change the result

Trauma survivors also need to form relationships built on trust. But several former inmates and their advocates said that in women’s prisons, close relationships can be criminalized.

Maria Moon, who spent 13 years in Illinois prisons, said she got more than one ticket for “sexual contact” for what she said was simply showing non-sexual affection towards friends. “You might be trying to console them because they had a death in the family, or they miss their children. It’s just what human beings do, but they look at it as sexual,” she said.

Moon said that by the time she left prison, she had internalized those rules and stopped showing affection. “It affected my relationships with my children because I didn’t realize that I wasn’t hugging as much, that I was being kinda cold,” she said. “My son called me out on it.”

People who have experienced trauma also need to feel empowered. But many women interviewed for this story instead report being disrespected and demeaned by prison staff.

“[Correctional officers] say things like, ‘That’s why you’re in here, you stupid bitch,’” wrote one inmate at the Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln, Illinois, whose name is not being used to protect her from retaliation. “I’m talked to like I’m an animal, fed like I’m an animal, and treated and live like an animal.”

Cosby says that the default techniques used by correctional officers to control inmates can also have a triggering effect — and can lead to disciplinary infractions.

“If I got a guy that’s like this big,” said Cosby, raising her arms, “and he’s standing this close to me and hollering and pointing, just because he can, I’m seeing him and I’m hearing him, but I’m also seeing my dad who beat my ass, and my baby daddy who beat my ass — all these other men.”

“If I tried to leave he grabs me and I tried to pull away, that’s a staff assault. I assaulted him. And now I’m seg,” Cosby said.

Benedict said that the policies and practices typically used to control populations in prisons are harmful to “all human beings.” But, she added, “they are having a unique and devastating impact on women.”

“What’s happening is deeply troubling, re-traumatizing and destructive not only for the women, but for staff, for taxpayers, for communities.”

Illinois’ rough road to reform

PHOTO BY BILLY HEALY

Illinois Department of Corrections officials, Public Information Officer Lindsay Hess, Women’s Division Chief Carolyn Gurski, and Warden Glen Austin, right, walk the grounds at Logan Correctional Center with reporter Jessica Pupovac, second from right.

Even when research is available, the road to reform can be obstructed by politics and haphazard planning. In 2010, in a cost-cutting move, Illinois closed its Women’s Division, which oversaw gender-specific programming. Then in 2013, in another effort aimed at saving money, the inmates at the state’s two largest women’s facilities were moved into Logan Correctional Center, previously a men’s facility. Staff, used to working with men, were not prepared to work with women and many of them resented the changes.

The following year, Deanne Benos, the former assistant director of IDOC, co-founded a non-profit called the Women’s Justice Initiative with Benedict in an attempt to transform correctional services for women. They partnered with the National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women and IDOC to launch an in-depth study of gender-responsive practices at Logan.

The study, released in 2016, revealed deep gender biases among staff. Some correctional officers at Logan told researchers that they believed the women were “worthless,” “crazy,” “talk too much” and “will never be anything more than a convict.”

“Segregation and other highly punitive responses are being overused despite the reality that these practices can trigger trauma, create the troubling behaviors they are designed to eliminate, and fail to create long-term behavior change,” the report concluded.

Illinois State Rep. Juliana Stratton (5th District), who then ran the Center for Public Safety and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago, was part of Benos and Benedict’s assessment team. Soon after the report’s release, she was sworn into the General Assembly. She quickly sponsored a bill, drafted by Benos and Benedict, to re-establish the Women’s Correctional Services Division — only this time, the division would be run by a chief trained in gender-responsive and trauma-informed corrections, with a legislative mandate to reform the way the state disciplines female inmates.

In June 2017 a bill was passed, although the mandate to reform discipline and sanctions was stripped out after opposition from the correctional officers’ union.

Click here to view related article: Small state, big ideas

Even without a mandate, then-Acting Warden Maggie Burke began making changes. She reviewed every ticket and every stay in solitary, and reduced the sanctions whenever she thought it was appropriate. She also tried to change what she saw as a lack of training in communication skills and a department-wide over-emphasis on firearms training and physical confrontation.

Burke received pushback from correctional officers, some of whom held a demonstration outside the prison, pointing to a spike in inmate-on-officer attacks. Data obtained by the Reporter backed up those claims, but showed that male inmates were also assaulting officers at higher rates.

Burke said it was precisely the officers’ well-being she was concerned about when she implemented reforms. When she was coordinator of Women and Family Services for IDOC, part of her job was to review video footage of women being forcibly removed from their cell.

“The amount of stress and trauma that I experienced just watching the videos, I was like, ‘We have to do this better,’” she said. “We’re setting up to fail, we’re setting ourselves up to fail, and we’re exposing ourselves to more trauma.”

Celebrating progress

Three months after Illinois’ Women’s Correctional Services Act was signed into law by Governor Bruce Rauner in 2017, advocates and formerly incarcerated women gathered at a homeless services organization in Chicago for a press conference. They touted the progress they said had already been made.

Benos said they were “celebrating the passage of the most comprehensive law on the books for a women’s prison and parole overhaul…with individuals on both sides of the bars coming together to make some true change.”

She highlighted changes in the disciplining of incarcerated women that had occurred in the past year and a half, since the 2016 audit. The number of women in segregation had dropped by half. (Compliance with a consent decree on the use of segregation may have also influenced those numbers.) And in the first six months of 2017, women had lost only 2,660 days of good credit, compared to 18,830 during the same time period in 2015, just prior to the audit.

For these changes, the speakers gave much credit to Burke.

“A year ago I stood in front of everyone and said, ‘We can do things better.’ And for the last year we have done things better,” Burke told the small crowd.

But just weeks later, Burke told colleagues’ of her decision to retire. She told the Reporter that she had put off retirement for a while, and with the bill’s passage, she decided it was time.

She has since been replaced by Glen Austin, who has been with IDOC for more than a decade. Despite multiple email requests, the department declined to provide information about any training he might have in gender-responsive corrections.

Since Burke’s retirement, systemwide reform has fallen largely to Carolyn Gurski, a three-decade IDOC veteran who in January 2018 was appointed Illinois’ new Women’s Division chief. Gurski talks with a slight Southern Illinois twang as she explains that, when she first became a correctional officer in 1989, she received “no training” on working with female offenders.

PHOTO BY BILL HEALY

Women’s Division Chief Caroline Gurski, Illinois Department of Corrections

“I didn’t even think about women being in prison, to be honest, in the academy,” she said.

Now, training is crucial to the changes that Gurski wants to make. The department recently added four hours of training on working with female inmates in their six-week academy. And all new correctional officers assigned to a female facility now go through a week-long training, designed by Benedict, where they learn more about women’s typical backgrounds, needs and communication styles. Since 2017, more than 200 Illinois correctional staff have received the training. It’s a significant number, but still only a small fraction of the total workforce at Logan, which exceeds 700 people.

On a March day at Logan, about 25 correctional officers sat in a large administrative room for the training, role-playing conflicts that might arise and discussing how to best respond. On the wall were flipboard sheets listing the preconceived notions that many officers had about female inmates when they stepped into the training: that they are “loud,” “disrespectful” and “argumentative.”

Trainer Tiona Farrington stood in front of the class, telling officers about the importance of de-escalating conflicts and imagining the perspective of the inmate. She stressed the need to take a deep breath and stay calm. And she told them to remember the key elements of any trauma-informed environment: safety, trust, collaboration, and empowerment.

Despite multiple requests, the Illinois Department of Corrections declined to provide data that would demonstrate whether they’ve reduced the number of low-level tickets and sanctions — other than segregation — for their female inmate population since the 2015 audit.

Trying to move on

PHOTO BY APRIL ALONSO

After spending twenty years in an Illinois prison, Monica Cosby became a community organizer at the Westside Justice Center in Chicago.

Since leaving Logan Correctional Center three years ago, Monica Cosby has been working on reconnecting with her three adult daughters — who were one, four, and seven when she was incarcerated.

She’s also fighting for the women she left behind. She’s become an outspoken activist, demanding better services for incarcerated and returning women. And she’s part of a new Statewide Women’s Justice Taskforce, which is monitoring the reforms required by Illinois’ new law.

“All I’m doing now is I promised I was going to do,” she said during an interview at the Westside Justice Center, where she is a community organizer. “And I always feel like I’m not doing enough.”

She added that she believes it will take more than laws and training to change the experiences of incarcerated women.

“Until there are radical changes in our culture and the way we value women overall — not just in the prison system, but in our culture that built the prison system — it’s going to continue to be this way.”

Jessica Pupovac is a Chicago-based freelance reporter and producer who specializes in covering the environment, criminal justice, and women’s issues. Her work has been featured on NPR and in the Chicago Reader and WTTW.com.

Kari Lydersen is a Chicago-based reporter, author and lecturer in the journalism graduate program at Northwestern University, where she heads the Social Justice & Investigative specialization.

Robert Benincasa of NPR and Matt Kiefer of The Chicago Reporter provided data support. Northwestern journalism students Sydney Boles, Natalya Carrico and Cailin Crowe contributed reporting. Additional support was provided by Illinois Humanities and the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.

Want more stories like this?

Get the latest from the Reporter delivered straight to your inbox. Subscribe to our free email newsletter.