Reimagining Prison

Executive Summary

Background

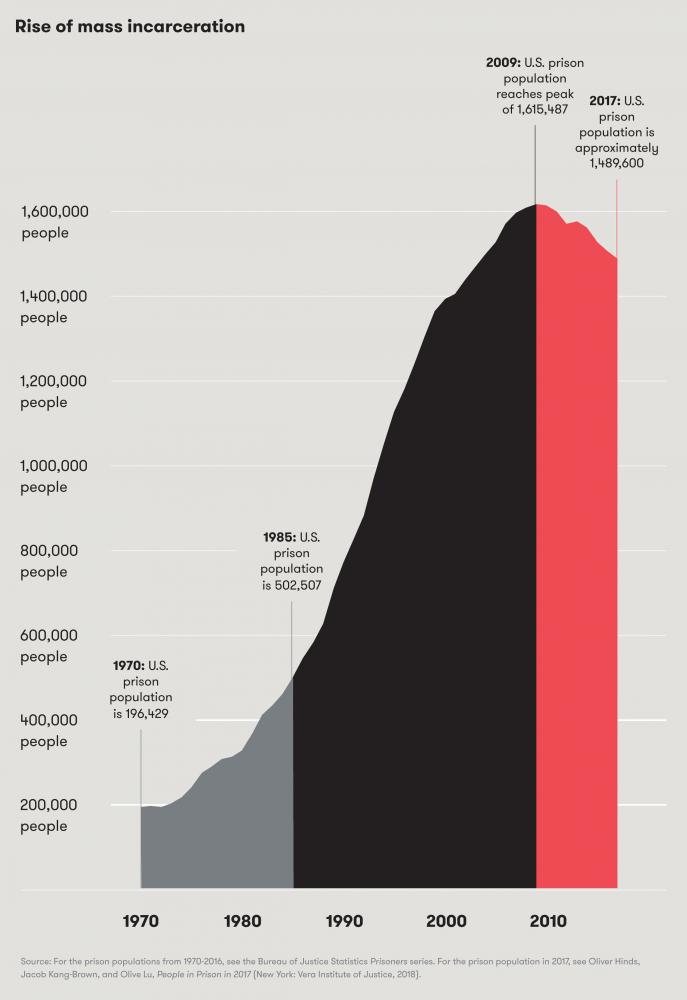

The United States holds approximately 1.5 million people in its state and federal prisons. Although this number has declined since its peak in 2009, mass incarceration is hardly a thing of the past. Even if the nation returned to the incarceration rates it experienced before 1970, more than300,000 people—approximately one per 1,000 residents—would still be held in U.S. prisons. And the conditions of that confinement are dismal. Prison in America is a place of severe hardship—a degree of hardship that is largely inconceivable to people who have not seen or experienced it themselves or through a loved one. It is an institution that causes individual, community, and generational pain and deprivation. For those behind the walls, prison is characterized by social and physical isolation, including severe restriction of personal movement, enforced idleness, insufficient basic care, a loss of meaningful personal contacting the deterioration of family relationships, and the denial of constitutional rights and avenues to justice. Those who work in prisons suffer too, with alarming rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide compared to the general population.

Beyond the walls of prison, incarceration’s impact is broad: mass imprisonment disrupts social networks, distorts social norms, and hollows out citizenship. Over this country’s long history of using prisons, American values of fairness and justice have been sacrificed to these institutions in the name of securing the common good of public safety. But the harsh conditions within prisons have been demonstrated neither to ensure safety behind the walls nor to prevent crime and victimization in the community. The story of American prisons is also a story of racism. We as a nation have not yet fully grappled with the ways in which prisons—how they have been used, the purposes they serve, who gets sent to them, and people’s experiences inside them—are intimately entwined with the legacy of slavery and generations of racial and social injustice. Built on a system of racist policies and practices that has disproportionately impacted people of color, mass incarceration has decimated the communities and families from which they come. It is time to acknowledge that this country has long used state punishment generally—and incarceration specifically—to subordinate racial and ethnic minorities.

The recent prison incident in South Carolina that left seven dead, as well as prison strikes across the country in2016 and 2018 protesting inhumane treatment, serve as tragic wake-up calls that something is fundamentally wrong inside America’s prisons. With a few limited exceptions, correctional practice today remains underpinned by retribution, deterrence, and incapacitation. These realities beg the question: isn’t there another way? We have failed to ask this question with sufficient seriousness and thoroughness. The time for us to do so is now. And so, to take a truly decisive step away from the past, America needs a new set of normative values on which to ground prison policy and practice—values that simultaneously recognize, interrogate, and unravel the persistent connections between racism and this country’s system of punishment. In this report, the Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) reimagines the how, what, and why of incarceration. And in so doing, we assert a new governing principle: human dignity. This principle dictates that “very human being possesses an intrinsic worth, merely by being human.” It applies to people living in prison as well as the corrections staff who work there.

Basing American corrections practice on the principle of human dignity both acknowledges and responds to this history of racial and ethnic oppression and the role formal state punishment systems have played in creating and perpetuating inequality. The United States’ stain of legal slavery and its denial of the personhood of black Americans have direct ties to the disproportionate representation of people of color among prison populations today. Grounding our prison system on the concept of human dignity is one step the country must take to come to terms with its history of racial and ethnic subordination.

But a system grounded in human dignity does more: it benefits all of us. Indeed, a society rooted in fairness and justice demands it. As improbable as this may seem to the skeptic, it may be persuasive to know that America would not be the first country to atone for its past of brutal, unforgivable dehumanization by embracing human dignity. Post-war, post-Holocaust Germany enshrined human dignity in its 1949 Basic Law, which states: “Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.” We need look no further.

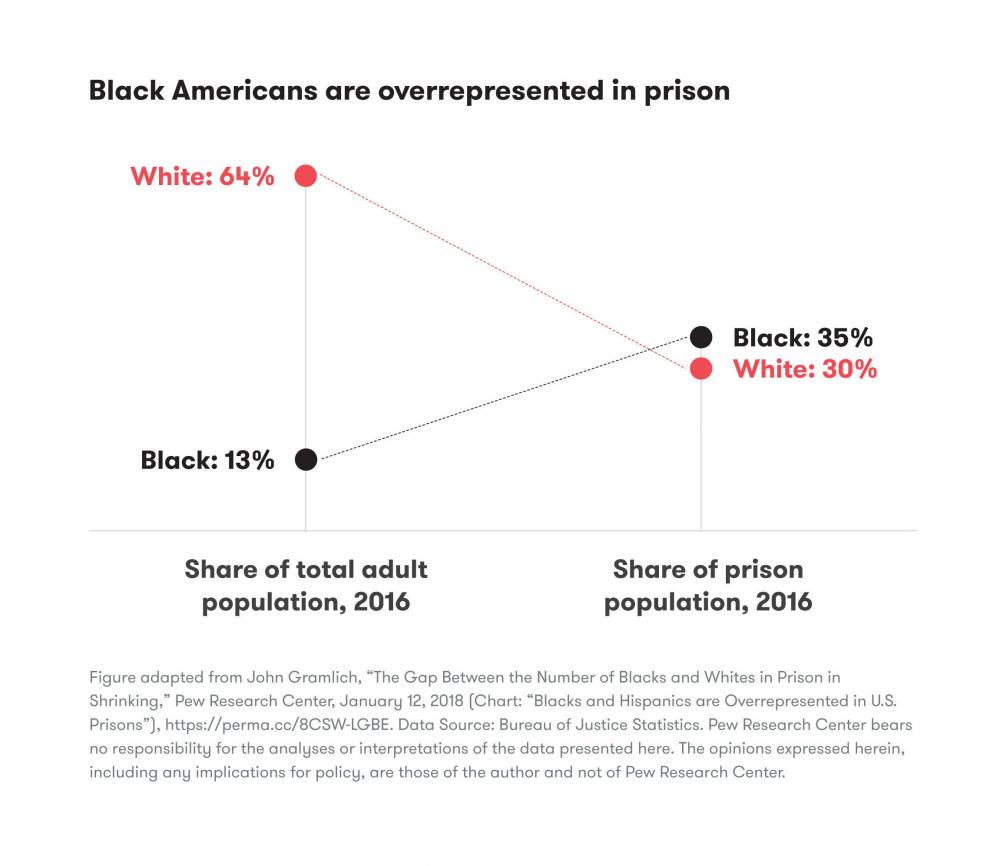

The American prison experience today

The report begins in Chapter 1: Examining prisons today by looking at who is in prison in the United States and what they experience. What we find is that those imprisoned are disproportionately people of color. This is most visible in the number of black Americans behind bars, although other groups—such as Latino and Native American people—are also over represented in prison in comparison to their presence in the general population. Today, black men and women make up just 13 percent of the country’s population, but they represent more than 35 percent of those in American prisons—making black Americans the largest racial or ethnic group subject to incarceration. This disproportionate representation happened by choice, not chance. It was the result of centuries of practices that targeted black people and criminalized the experience of being black in America. Prison also disproportionately impacts other marginalized populations: people who are poor, those who have mental illnesses or substance use issues, those with lower levels of education, and those who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. What is life like for people in prison? With few exceptions, the prison experience today is harsh, restrictive, and dehumanizing. Prison life results in the loss of each incarcerated person’s sense of self, autonomy, and capacity to control his or her own destiny. In its place rises a new“carceral identity”—one reinforced by the strict social arrangements inside prisons and the power imbalance between corrections officers and incarcerated people. These defining characteristics are fostered by the features that make up the prison experience:

› the design and physical layout of prison buildings, which contribute to dehumanization and institutionalization;

› the twin experiences of overcrowding and isolation(through the use of solitary confinement for punishment and control and the siting of prisons in rural areas, away from family, friends, and community supports);

› a lack of basic necessities, including adequate and healthy food and essential sanitary items;

› a dearth of meaningful activities and opportunities for paid work, vocational training, or educational programming;

› limited connections to the outside world and obstacles to maintaining personal relationships with family and friends;

› lasting trauma from the hyper vigilance required to navigate the experience of prison life itself; and

› the loss of constitutional and civic rights.

Despite the lowest crime rates in decades, we have 1.5 million people behind prison bars. One and a half million—2.2 million if you count jails. Let those numbers sink in. We have lost generations of young men and women, particularly young men of color, to long and brutal prison terms.

Staff, too, are victims of the prison environment as it exists today. Placed in a high stress environment with low pay, they suffer from job stress and poor health outcomes while trying to maintain order with limited training. American history, race, and prison

American history, race, and prison

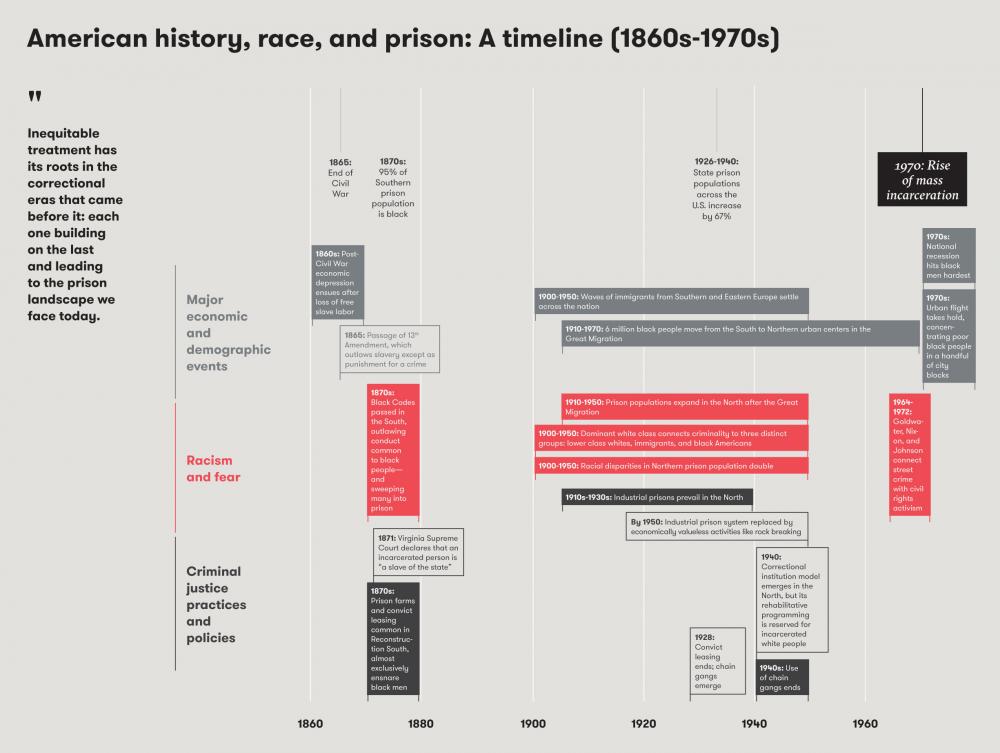

The American prison system as it stands today did not arise fully formed out of 20th century politics and policies; rather it is interwoven with this country’s deep and divisive history of unequal race relations. Chapter 2: American history, race, and prison demonstrates that—though marked by distinct eras throughout U.S. history—incarceration in this country has long had two significant features: (1) growth in the number of people imprisoned; and (2) disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities and others with outsider status, defined broadly as those not belonging to the dominant political and social community in power. In the Reconstruction South, prisons were used to continue to exact control over newly freed black people through brutal practices like convict leasing and prison farms, which have been said to mimic slavery in all but name. In the North, during the Great Migration between 1910 and 1970, black people were similarly—though less overtly—funneled into prison in racially discriminatory and racially disproportionate ways.

In the late 1960s through the 1990s, politicians started to employ a “tough on crime” message that linked protests of the Civil Rights era to black criminality, and then further in response to a surge in violent crime in the 1970s and1980s, when the nation’s policymakers began to use lengthy and mandatory prison sentences as the primary response to offenses at all levels, leading to the era of mass incarceration. And, although prison populations have been declining in the past few years, the United States is still a world leader in incarceration, and prison conditions continue to be harsh.

Human dignity as the guiding principle

To radically change this history will require radical changes in prison practice. In Chapter 3: Human dignity as the guiding principle, we call for a transformation in the goals and experience of incarceration in this country. Vera proposes that a bold but simple value govern all facets of this newly shaped prison system: the value of human dignity. Human dignity is a concept that has deep and ancient philosophical underpinnings and is well established as a modern legal principle both in the United States and abroad. The principle of human dignity recognizes every person’s self-worth and capacity for self-control, autonomy, and rationality. It as an inherent value that inures to all human beings and, in Vera’s vision, one that must serve as a cardinal principle dictating how the prison system must organize itself from top to bottom. A commitment to human dignity does not undermine the fundamental correctional priorities of safety and security. Rather, human dignity demands that everyone behind the walls—those incarcerated as well as staff—is kept safe and secure.

Human dignity may seem an amorphous precept on which to hang the implementation of a nation’s corrections system. And so, to give life to this governing tenet in the real world of the nation’s prisons, Vera proposes the three practice principles below.

To take a truly decisive step away from the past, America needs a new set of normative values on which to ground prison policy and practice—values that simultaneously recognize, interrogate, and unravel the heretofore persistent connections between racism and this country’s systems of punishment.

› Practice principle 1: Respect the intrinsic worth of each human being. This principle prohibits practices that degrade or demean a person. Instead, policies should serve to humanize people in prison. A system operating under this practice principle would, for example, instruct staff to call incarcerated people by their names; provide high quality health care at the prison; permit incarcerated people to choose their own clothing; provide an adequate supply of hygienic products; serve sufficient amounts of edible and healthy food; and institute meaningful protection from physical and emotional abuse in the prison, whether perpetrated by staff or other incarcerated people.

› Practice principle 2: Elevate and support personal relationships. Vera’s second practice principle focuses allowing people who are living in prison to develop and maintain relationships with others and it prohibits actions that serve to hamper such interactions. A person’s inherent worth and sense of dignity is often bound up in relationships with others. In the context of a prison, this means relationships between those living in prison, between corrections staff and residents, and between incarcerated people and their families and friends on the outside. This principle can be put into practice through a focus on prison architecture and design. Prison systems can renovate old facilities or build new ones that minimize noise, provide outdoor recreation spaces, include day rooms for group activities and personal interactions between staff and residents, and have kitchens where incarcerated people can prepare food for themselves and others. Relationships also must go beyond prison walls, and a prison system that centers interpersonal relationships should house incarcerated people in facilities that are as close as possible to their homes and loved ones. Prisons should also develop generous in-person, phone, and email visitation policies and provide people who are incarcerated with meaningful opportunities to receive furloughs for family events or to participate in work or educational programs in preparation for reentry.

› Practice principle 3: Respect a person’s capacity to grow and change. The inherent dignity of a human being includes a person’s capacity for self-control, empowerment, autonomy, and rationality. This third practice principle requires prisons to provide opportunities for incarcerated people to pursue productive activities, grow, and develop. Prisons should work with incarcerated people to create case plans with goals for employment, education, health, and family; provide access to high quality education at all levels; ensure that reading material is available; provide behavioral health treatment; give people the opportunity to work and be fairly compensated for it; offer restorative justice programs; and engage incarcerated people in the creation and enforcement of in-unit rules.

Achieving human dignity today

The vision articulated in this report demands significant changes in this country’s corrections systems. The sheer scale of America’s prison infrastructure makes the implementation of a comprehensive human dignity-based system enormous, resource-intensive, and dependent on political leadership that is currently all but nonexistent. Our vision is one that necessitates a dramatic shrinking of our system of mass incarceration and an honest reckoning about resources. But that is no excuse for helpless paralysis. Every jurisdiction in this country—local, state, and federal—can take tangible, beginning steps today to begin to infuse human dignity into its correctional operations.

Chapter 4: Achieving human dignity today shows how this is already occurring in several places around the country. On five separate visits over the last five years, Vera and the Prison Law Office, together and separately, introduced officials from at least a dozen states to several different Northern European corrections systems where human dignity plays a central role. Those who participated in these trips came back with a new outlook on the role and purpose of corrections. Many states, including Connecticut, Idaho, North Dakota, and Pennsylvania, have since taken steps—both big and small—to introduce human dignity into their corrections systems starting now.

Connecticut’s experience is particularly instructive. There, in partnership with Vera, the Cheshire Correctional institution piloted a young adult unit based on human dignity tenets. Called T.R.U.E. (an acronym for Truthfulness, Respectfulness, Understanding, and Elevating), the unit houses men aged 18 to 25 living under many of the conditions proposed in this report, including elements of autonomy and personal choice, freedom of movement, individual responsibility, goal-setting, mentorship, and therapeutic programming. The environment fosters interpersonal relationships among those incarcerated, as well as between them and their families, their mentors, and prison staff. The impact on both the young men who reside there and the prison staff who volunteered to work on the unit has been tremendous. In 18 months, there have been no acts of violence. Solitary is no longer used. Young adults report feeling safer, more prepared to succeed, more connected to family, and more fairly treated. Staff report greater calm and satisfaction. While still too early to be definitive, recidivism is lower. These are changes wrought when practices reveal the humanity of those on each side of the equation to the other and allow them to meet in that space, communicate with respect, and move toward common goals. Inspired by the success of its T.R.U.E. program, Connecticut opened a similar unit in May 2018 at York correctional Institution, the state’s only prison for women, and plans to create another one at Cheshire. Other jurisdictions are also joining the movement to reimagine the purpose of young adult confinement. In fall 2017, Vera began a partnership with the Middlesex County Sheriff’s Office in Massachusetts, which opened a similar young adult unit in its jail in February 2018. Shortly after that, through a competitive application process, South Carolina was selected to join these partners in transforming custody for young adults.

Though T.R.U.E. is an enormously promising model ,it does not completely reimagine prison in the way this report envisions. The unit, however altered, is a slightly renovated wing of a larger facility. It still looks and feels like the quintessential American prison. Only one age group is eligible for its benefits—an advantage that doesn’t go unnoticed by the rest of the prison’s population. The people in the unit still wear uniforms, and the food and hygiene products that are offered remain the same as those offered to the rest of the prison. But it is emphatically a place to begin. The T.R.U.E. experience highlights that reimagining prison in America need not wait until total prison population declines or more prisons are built closer to where the incarcerated population lives. Reimagining prison is possible now. This report provides an aspirational vision, one that systems can consider, debate, and experiment with today, with the hope that by laying the necessary foundation of inalienable human dignity something new and wholly different will come tomorrow.

But this work must go beyond the corrections sphere. This is an American issue, and one that all Americans should care about. To truly effect radical change will require all of us to take action, not just those who administer and work in our nation’s prisons. Policymakers, advocates, the media, criminal justice system stakeholders, and even members of the public must join together to shine a light on current practices and to say, once and for all, that they cannot stand.

We call on ourselves and others to reshape the practice of imprisonment by grounding it in the foundational principle of human dignity.

Vera Institute for Justice

Mission

To drive change. To urgently build and improve justice systems that ensure fairness, promote safety, and strengthen communities.

Achieving Our Mission

We work with others who share our vision to tackle the most pressing injustices of our day—from the causes and consequences of mass incarceration, racial disparities, and the loss of public trust in law enforcement, to the unmet needs of the vulnerable, the marginalized, and those harmed by crime and violence.

Ruth Delaney - Program Manager

Ruth provides technical assistance to states seeking to implement new policies and practices, and conducts research into justice policy trends. Current and past projects include assistance to New Jersey as part of Vera’s national demonstration project Pathways from Prison to Post-Secondary Education, and statewide policy implementation assistance to Arkansas, Delaware, and South Carolina under the Bureau of Justice Assistance’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative. She has co-authored several reports at Vera, including Incarceration’s Front Door: The Misuse of Jails in America and Price of Prisons: What Incarceration Costs Taxpayers. Before joining Vera, Ruth worked with organizations devoted to poverty reduction in the United States and to securing rule of law in post-conflict countries. She also held positions in the JEHT Foundation’s criminal and juvenile justice grant programs. Ruth holds an MA in women’s studies from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and is currently pursuing a PhD in sociology from the same institution. She also holds a BA in English from Manhattanville College.

Ram Subramanian - Editorial Director

Ram joined Vera in 2010. He is a lawyer who has worked for many years on issues of democracy, judicial independence, sexual and other kinds of political violence, and on human rights issues more broadly in Zimbabwe and South Africa. He has studied and worked in many parts of the world. He has an undergraduate degree from Wesleyan University in Connecticut, a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, and a law degree from the University of Melbourne Law School.

Alison Shames - Former Associate Director, Center on Sentencing and Corrections

As associate director of the Center on Sentencing and Corrections between 2008 and 2013, Alison managed staff, oversaw budgets, developed grant proposals, and directed projects. Her work included helping Illinois pass and implement its Crime Reduction Act of 2009, which legislated the use of evidence-based practices throughout the criminal justice system; facilitating county and state steering committees in Alabama to improve community-based supervision practices and address prison overcrowding; drafting and editing Vera reports on the fiscal crisis and sentencing trends; convening a national conference on performance incentive funding programs; and managing the Justice Reinvestment Initiative for Vera. Previously, Alison worked in Sydney, Australia, where she served as executive officer to the Committee of Criminal Justice CEOs in the Attorney General’s Department of New South Wales. Before that, Alison was the state copyright manager for the state of New South Wales and corporate counsel for Fairfax Media, one of Australia’s largest media companies. Immediately following law school, Alison clerked for U.S. District Court Judge Sarah Vance in New Orleans. Alison has a BA from the University of Pennsylvania and a JD from New York University School of Law.

Nicholas Turner - President and Director

Nicholas Turner joined Vera as its fifth president and director in August, 2013. Under his leadership, Vera is pursuing core priorities of ending the misuse of jails, transforming conditions of confinement, and ensuring that justice systems more effectively serve America's growing minority communities. To that end, Vera is working across the country to reduce jail populations in major cities, shrink the number of people held in solitary confinement, and develop systems to ensure that police are held accountable for building public trust. Vera is also using new tools and leveraging its half-century of experience working on the frontlines of justice to shape public debate at a time when interest in justice is at a new height.

Recent major initiatives include a high-level study tour of the German justice system that was covered by 60 Minutes, a multimedia public engagement campaign exploring the legacy of the 1994 Crime Bill, and a first-of-its-kind interactive data tool that sheds new light on the role jails play in mass incarceration.

Nick previously served at Vera from 1998 to 2007. During his first tenure, he developed ideas for demonstration projects aimed at keeping troubled youth out of the justice system and easing reentry for adult prisoners. He also guided the expansion of Vera’s national work, launching and directing Vera’s state sentencing and corrections initiative, while supervising Vera’s domestic violence projects and the creation of its youth justice program. As vice president and chief program officer, Nick was responsible for the development and launch of the Prosecution and Racial Justice Program and the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons.

Prior to re-joining Vera, Nick was a managing director at The Rockefeller Foundation, where he was a member of the foundation’s senior leadership team and a co-leader of its global urban efforts. He provided leadership and strategic direction on key initiatives, including transportation policy reform in the U.S. to promote social, economic, and environmental interests, and redevelopment in New Orleans to advance racial and socioeconomic integration.

Earlier in his legal career, Nick was an associate in the litigation department of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison in New York from 1997 to 1998. He was a judicial clerk for the Honorable Jack. B. Weinstein, Senior United States District Judge in Brooklyn from 1996 to 1997. Before attending Yale Law School, he worked with court-involved, homeless, and troubled young people at Sasha Bruce Youthwork, a Washington, DC youth services organization, from 1989 to 1993.

Nick is author of several op-eds, including “A Home After Prison” (the New York Times), “What We Learned from German Prisons” (with Jeremy Travis, president of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, the New York Times), “The Steep Cost of America’s High Incarceration Rate” (with Robert Rubin, co-chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and a former U.S. Treasury secretary, the Wall Street Journal) and “Treating Prisoners with Dignity Can Reduce Crime” (with John Wetzel, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, National Journal’s The Next America). He has also published a number of articles on criminal justice, including Politics, Public Service, and Professionalism: Conflicting Themes in the Invention and Evaluation of Community Prosecution (with Chris Stone, 1999) and “The Cost of Avoiding Injustice by Guideline Circumventions,” in Federal Sentencing Reporter (with the Honorable Jack B. Weinstein, 1997).

In 2015, Nick joined the advisory council of the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, a new, independent nonprofit aiming to eliminate the gaps in opportunity and achievement for boys and young men of color. He currently serves on the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform and the Advisory Board to New York City’s Children’s Cabinet. Nick has previously served on the boards of the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, Living Cities, Center for Working Families, and St. Christopher’s Inc.