Impeach Donald Trump (long)

On January 20, 2017, Donald Trump stood on the steps of the Capitol, raised his right hand, and solemnly swore to faithfully execute the office of president of the United States and, to the best of his ability, to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. He has not kept that promise.

Instead, he has mounted a concerted challenge to the separation of powers, to the rule of law, and to the civil liberties enshrined in our founding documents. He has purposefully inflamed America’s divisions. He has set himself against the American idea, the principle that all of us—of every race, gender, and creed—are created equal.

This is not a partisan judgment. Many of the president’s fiercest critics have emerged from within his own party. Even officials and observers who support his policies are appalled by his pronouncements, and those who have the most firsthand experience of governance are also the most alarmed by how Trump is governing.

“The damage inflicted by President Trump’s naïveté, egotism, false equivalence, and sympathy for autocrats is difficult to calculate,” the late senator and former Republican presidential nominee John McCain lamented last summer. “The president has not risen to the mantle of the office,” the GOP’s other recent nominee, the former governor and now senator Mitt Romney, wrote in January.

The oath of office is a president’s promise to subordinate his private desires to the public interest, to serve the nation as a whole rather than any faction within it. Trump displays no evidence that he understands these obligations. To the contrary, he has routinely privileged his self-interest above the responsibilities of the presidency. He has failed to disclose or divest himself from his extensive financial interests, instead using the platform of the presidency to promote them. This has encouraged a wide array of actors, domestic and foreign, to seek to influence his decisions by funneling cash to properties such as Mar-a-Lago (the “Winter White House,” as Trump has branded it) and his hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue. Courts are now considering whether some of those payments violate the Constitution.

More troubling still, Trump has demanded that public officials put their loyalty to him ahead of their duty to the public. On his first full day in office, he ordered his press secretary to lie about the size of his inaugural crowd. He never forgave his first attorney general for failing to shut down investigations into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia, and ultimately forced his resignation. “I need loyalty. I expect loyalty,” Trump told his first FBI director, and then fired him when he refused to pledge it.

Trump has evinced little respect for the rule of law, attempting to have the Department of Justice launch criminal probes into his critics and political adversaries. He has repeatedly attacked both Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Special Counsel Robert Mueller. His efforts to mislead, impede, and shut down Mueller’s investigation have now led the special counsel to consider whether the president obstructed justice.

As for the liberties guaranteed by the Constitution, Trump has repeatedly trampled upon them. He pledged to ban entry to the United States on the basis of religion, and did his best to follow through. He has attacked the press as the “enemy of the people” and barred critical outlets and reporters from attending his events. He has assailed black protesters. He has called for his critics in private industry to be fired from their jobs. He has falsely alleged that America’s electoral system is subject to massive fraud, impugning election results with which he disagrees as irredeemably tainted. Elected officials of both parties have repeatedly condemned such statements, which has only spurred the president to repeat them.

These actions are, in sum, an attack on the very foundations of America’s constitutional democracy.

50 moments that define Trump’s presidency

The electorate passes judgment on its presidents and their shortcomings every four years. But the Framers were concerned that a president could abuse his authority in ways that would undermine the democratic process and that could not wait to be addressed. So they created a mechanism for considering whether a president is subverting the rule of law or pursuing his own self-interest at the expense of the general welfare—in short, whether his continued tenure in office poses a threat to the republic. This mechanism is impeachment.

Trump’s actions during his first two years in office clearly meet, and exceed, the criteria to trigger this fail-safe. But the United States has grown wary of impeachment. The history of its application is widely misunderstood, leading Americans to mistake it for a dangerous threat to the constitutional order.

That is precisely backwards. It is absurd to suggest that the Constitution would delineate a mechanism too potent to ever actually be employed. Impeachment, in fact, is a vital protection against the dangers a president like Trump poses. And, crucially, many of its benefits—to the political health of the country, to the stability of the constitutional system—accrue irrespective of its ultimate result. Impeachment is a process, not an outcome, a rule-bound procedure for investigating a president, considering evidence, formulating charges, and deciding whether to continue on to trial.

The fight over whether Trump should be removed from office is already raging, and distorting everything it touches. Activists are radicalizing in opposition to a president they regard as dangerous. Within the government, unelected bureaucrats who believe the president is acting unlawfully are disregarding his orders, or working to subvert his agenda. By denying the debate its proper outlet, Congress has succeeded only in intensifying its pressures. And by declining to tackle the question head-on, it has deprived itself of its primary means of reining in the chief executive.

With a newly seated Democratic majority, the House of Representatives can no longer dodge its constitutional duty. It must immediately open a formal impeachment inquiry into President Trump, and bring the debate out of the court of public opinion and into Congress, where it belongs.

Democrats picked up 40 seats in the House of Representatives in the 2018 elections. Despite this clear rebuke of Trump—and despite all that is publicly known about his offenses—party elders remain reluctant to impeach him. Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the House, has argued that it’s too early to talk about impeachment. Many Democrats avoided discussing the idea on the campaign trail, preferring to focus on health care. When, on the first day of the 116th Congress, a freshman representative declared her intent to impeach Trump and punctuated her comments with an obscenity, she was chastised by members of the old guard—not just for how she raised the issue, but for raising it at all.

In no small part, this trepidation is due to the fact that the last effort to remove an American president from office ended in political fiasco. When the House impeached Bill Clinton, in 1998, his popularity soared; in the Senate, even some Republicans voted against convicting him of the charges.

Pelosi and her antediluvian leadership team served in Congress during those fights two decades ago, and they seem determined not to repeat their rivals’ mistakes. Polling has shown significant support for impeachment over the course of Trump’s tenure, but the most favorable polls still indicate that it lacks majority support. To move against Trump now, Democrats seem to believe, would only strengthen the president’s hand. Better to wait for public opinion to turn decisively against him and then use impeachment to ratify that view. This is the received wisdom on impeachment, the overlearned lesson of the Clinton years: House Republicans got out ahead of public opinion, and turned a president beset by scandal into a sympathetic figure.

Instead, Democrats intend to be a thorn in Trump’s side. House committees will conduct hearings into a wide range of issues, calling administration officials to testify under oath. They will issue subpoenas and demand documents, emails, and other information. The chair of the Ways and Means Committee has the power to request Trump’s elusive tax returns from the IRS and, with the House’s approval, make them public.

Other institutions are already acting as brakes on the Trump presidency. To the president’s vocal frustration, federal judges have repeatedly enjoined his executive orders. Robert Mueller’s investigation has brought convictions of, or plea deals from, key figures in his campaign as well as his administration. Some Democrats are clearly hoping that if they stall for long enough, Mueller will deliver them from Trump, obviating the need to act themselves.

But Congress can’t outsource its responsibilities to federal prosecutors. No one knows when Mueller’s report will arrive, what form it will take, or what it will say. Even if Mueller alleges criminal misconduct on the part of the president, under Justice Department guidelines, a sitting president cannot be indicted. Nor will the host of congressional hearings fulfill that branch’s obligations. The view they will offer of his conduct will be both limited and scattershot, focused on discrete acts. Only by authorizing a dedicated impeachment inquiry can the House begin to assemble disparate allegations into a coherent picture, forcing lawmakers to consider both whether specific charges are true and whether the president’s abuses of his power justify his removal.

Waiting also presents dangers. With every passing day, Trump further undermines our national commitment to America’s ideals. And impeachment is a long process. Typically, the House first votes to open an investigation—the hearings would likely take months—then votes again to present charges to the Senate. By delaying the start of the process, in the hope that even clearer evidence will be produced by Mueller or some other source, lawmakers are delaying its eventual conclusion. Better to forge ahead, weighing what is already known and incorporating additional material as it becomes available.

Critics of impeachment insist that it would diminish the presidency, creating an executive who serves at the sufferance of Congress. But defenders of executive prerogatives should be the first to recognize that the presidency has more to gain than to lose from Trump’s impeachment. After a century in which the office accumulated awesome power, Trump has done more to weaken executive authority than any recent president. The judiciary now regards Trump’s orders with a jaundiced eye, creating precedents that will constrain his successors. His own political appointees boast to reporters, or brag in anonymous op-eds, that they routinely work to counter his policies. Congress is contemplating actions on trade and defense that will hem in the president. His opponents repeatedly aim at the man but hit the office.

Democrats’ fear—that impeachment will backfire on them—is likewise unfounded. The mistake Republicans made in impeaching Bill Clinton wasn’t a matter of timing. They identified real and troubling misconduct—then applied the wrong remedy to fix it. Clinton’s acts disgraced the presidency, and his lies under oath and efforts to obstruct the investigation may well have been crimes. The question that determines whether an act is impeachable, though, is whether it endangers American democracy. As a House Judiciary Committee staff report put it in 1974, in the midst of the Watergate investigation: “The purpose of impeachment is not personal punishment; its function is primarily to maintain constitutional government.” Impeachable offenses, it found, included “undermining the integrity of office, disregard of constitutional duties and oath of office, arrogation of power, abuse of the governmental process, adverse impact on the system of government.”

Trump’s bipartisan critics are not merely arguing that he has lied or dishonored the presidency. The most serious allegations against him ultimately rest on the charge that he is attacking the bedrock of American democracy. That is the situation impeachment was devised to address.

Video: It’s Time to Impeach Trump

Watch here.

After the House impeaches a president, the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority in the Senate to remove him from office. Opponents of impeachment point out that, despite the greater severity of the prospective charges against Trump, there is little reason to believe the Senate is more likely to remove him than it was to remove Clinton. Indeed, the Senate’s Republican majority has shown little will to break with the president—though that may change. The process of impeachment itself is likely to shift public opinion, both by highlighting what’s already known and by bringing new evidence to light. If Trump’s support among Republican voters erodes, his support in the Senate may do the same. One lesson of Richard Nixon’s impeachment is that when legislators conclude a presidency is doomed, they can switch allegiances in the blink of an eye.

But this sort of vote-counting, in any case, misunderstands the point of impeachment. The question of whether impeachment is justified should not be confused with the question of whether it is likely to succeed in removing a president from office. The country will benefit greatly regardless of how the Senate ultimately votes. Even if the impeachment of Donald Trump fails to produce a conviction in the Senate, it can safeguard the constitutional order from a president who seeks to undermine it. The protections of the process alone are formidable. They come in five distinct forms.

The first is that once an impeachment inquiry begins, the president loses control of the public conversation. Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton each discovered this, much to their chagrin. Johnson, the irascible Tennessee Democrat who succeeded to the presidency in 1865 upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, quickly found himself at odds with the Republican Congress. He shattered precedents by delivering a series of inflammatory addresses that dominated the headlines and forced his opponents into a reactive posture. The launching of impeachment inquiries changed that. Day after day, Congress held hearings. Day after day, newspapers splashed the proceedings across their front pages. Instead of focusing on Johnson’s fearmongering, the press turned its attention to the president’s missteps, to the infighting within his administration, and to all the things that congressional investigators believed he had done wrong.

It isn’t just the coverage that changes. When presidents face the prospect of impeachment, they tend to discover a previously unsuspected capacity for restraint and compromise, at least in public. They know that their words can be used against them, so they fume in private. Johnson’s calls for the hanging of his political opponents yielded quickly to promises to defer to their judgment on the key questions of the day. Nixon raged to his aides, but tried to show a different face to the country. “Dignity, command, faith, head high, no fear, build a new spirit,” he told himself. Clinton sent bare-knuckled proxies to the television-news shows, but he and his staff chose their own words carefully.

Trump is easily the most pugilistic president since Johnson; he’s never going to behave with decorous restraint. But if impeachment proceedings begin, his staff will surely redouble its efforts to curtail his tweeting, his lawyers will counsel silence, and his allies on Capitol Hill will beg for whatever civility he can muster. His ability to sidestep scandal by changing the subject—perhaps his greatest political skill—will diminish.

As Trump fights for his political survival, that struggle will overwhelm other concerns. This is the second benefit of impeachment: It paralyzes a wayward president’s ability to advance the undemocratic elements of his agenda. Some of Trump’s policies are popular, and others are widely reviled. Some of his challenges to settled orthodoxies were long overdue, and others have proved ill-advised. These are ordinary features of our politics and are best dealt with through ordinary electoral processes. It is, rather, the extraordinary elements of Trump’s presidency that merit the use of impeachment to forestall their success: his subversion of the rule of law, attacks on constitutional liberties, and advancement of his own interests at the public’s expense.

The Mueller probe as well as hearings convened by the House and Senate Intelligence Committees have already hobbled the Trump administration to some degree. It will face even more scrutiny from a Democratic House. White House aides will have to hire personal lawyers; senior officials will spend their afternoons preparing testimony. But impeachment would raise the scrutiny to an entirely different level.

In part, this is because of the enormous amount of attention impeachment proceedings garner. But mostly, the scrutiny stems from the stakes of the process. The most a president generally has to fear from congressional hearings is embarrassment; there is always an aide to take the fall. Impeachment puts his own job on the line, and demands every hour of his day. The rarest commodity in any White House is time, that of the president and his top advisers. When it’s spent watching live hearings or meeting with lawyers, the administration’s agenda suffers. This is the irony of congressional leaders’ counseling patience, urging members to simply wait Trump out and use the levers of legislative power instead of moving ahead with impeachment. There may be no more effective way to run out the clock on an administration than to tie it up with impeachment hearings.

credits: Everett Historical; Charles Tasnadi; J. Scott Applewhite / AP // The Atlantic

But the advantages of impeachment are not merely tactical. The third benefit is its utility as a tool of discovery and discernment. At the moment, it is often hard to tell the difference between wild-eyed conspiracy theories and straight narrations of the day’s news. Some of what is alleged about Trump is plainly false; much of it might be true, but lacks supporting evidence; and many of the best-documented claims are quickly forgotten, lost in the din of fresh allegations. This is what passes for due process in the court of public opinion.

The problem is not new. When Congress first opened the Johnson impeachment hearings, for instance, the committee spent two months chasing rumor and innuendo. It heard allegations that Johnson had sent a secret letter to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis; that he had associated with a “disreputable woman” and, through her, sold pardons; that he had transferred ownership of confiscated railroads as political favors; even that he had conspired with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. The congressman who made that last claim was forced to admit to the committee pursuing impeachment that what he possessed “was not that kind of evidence which would satisfy the great mass of men”—he had simply based the accusation on his belief that every vice president who succeeds to the highest office murders his predecessor.

There was public value, though, in these investigations. The charges had already been leveled; they were circulating and shaping public opinion. Spread by a highly polarized, partisan press, they could not be dispelled or disproved. But once Congress initiated the process of impeachment, the charges had to be substantiated. And that meant taking them from the realm of rhetoric into the province of fact. Many of the claims against Johnson failed to survive the journey. Those that did eventually helped form the basis for his impeachment. Separating them out was crucial.

The process of impeachment can also surface evidence. The House Judiciary Committee began its impeachment hearings against Nixon in October 1973, well before the president’s complicity in the Watergate cover-up was clear. In April 1974, as part of those hearings, the Judiciary Committee subpoenaed 42 White House tapes. In response, Nixon released transcripts of the tapes that were so obviously expurgated that a district judge approved a subpoena from the special prosecutor for the tapes themselves. That demand, in turn, eventually produced the so-called smoking-gun tape, a recording of Nixon authorizing the CIA to shut down the FBI’s investigation into Watergate. The evidence that drove Nixon from office thus emerged as a consequence of the impeachment hearings; it did not spark them. The only way for the House to find out what Trump has actually done, and whether his conduct warrants removal, is to start asking.

That is not to say that impeachment hearings against Trump would be sober and orderly. The Clinton hearings were something of a circus, and the past two years on Capitol Hill suggest that any Trump hearings will be far worse. The president’s stalwart defenders are already attacking the integrity of potential witnesses and airing their own conspiracy theories; an attempt to smear Mueller with sexual-misconduct claims collapsed spectacularly in October. His accusers, meanwhile, hurl epithets and invective. In Congress, Trump’s most committed detractors might be tempted to follow the bad example of the Clinton impeachment, when, instead of conducting extensive hearings to weigh potential charges, House Republicans short-circuited the process—taking the independent counsel’s conclusions, rushing them to the floor, and voting to impeach in a lame-duck session. Trump’s opponents need to put their faith in the process, empowering a committee to consider specific charges, weigh the available evidence, and decide whether to proceed.

Hosting that debate in Congress yields a fourth benefit: defusing the potential for an explosion of political violence. This is a rationale for impeachment first offered at the Constitutional Convention, in 1787. “What was the practice before this in cases where the chief Magistrate rendered himself obnoxious?” Benjamin Franklin asked his fellow delegates. “Why, recourse was had to assassination in wch. he was not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character.” A system without a mechanism for removing the chief executive, he argued, offered an invitation to violence. Just as the courts took the impulse toward vigilante justice and safely channeled it into the protections of the legal system, impeachment took the impulse toward political violence and safely channeled it into Congress.

Nixon’s presidency was marked by an upsurge in political terrorism. In just its first 16 months, 4,330 bombings claimed 43 lives. As the Vietnam War wound down and the militant left began to lose its salience, it made opposition to the president its new rallying cry. “Impeach Nixon and jail him for his major crimes,” the Weather Underground demanded in its manifesto, Prairie Fire, in July 1974. “Nixon merits the people’s justice.” But that seemingly radical demand, intended to expose the inadequacy of the regular constitutional order, ironically proved the opposite point. By the end of the month, the House Judiciary Committee had approved three articles of impeachment; in early August, Nixon resigned. The ship of state, it turned out, had the capacity to right itself. The Weather Underground continued its slide into irrelevance, and political violence eventually receded.

The current moment is different, of course. Today, the left is again radicalizing, but the overwhelming majority of political violence is committed by the far right, albeit on a considerably smaller scale than in the Nixon era. Trump himself has warned that “the people would revolt” if he were impeached, a warning that echoes earlier eras. When Congress debated impeachment in 1868, some likewise predicted that it would provoke Andrew Johnson’s most ardent supporters to violence. “We are evidently on the eve of a revolution that may, should an appeal be taken to arms, be more bloody than that inaugurated by the firing on Fort Sumter,” warned The Boston Post.

The predictions were wrong then, as Trump’s are likely wrong now. The public understood that once the impeachment process began, the real action would take place in Congress, and not in the streets. Johnson knew that inciting his supporters to violence would erode congressional support just when he needed it most. That seems the most probable outcome today as well. If impeached, Trump would lose the luxury of venting his resentments before friendly crowds, stirring their anger. His audience, by political necessity, would become a few dozen senators in Washington.

And what if the Senate does not convict Trump? The fifth benefit of impeachment is that, even when it fails to remove a president, it severely damages his political prospects. Johnson, abandoned by Republicans and rejected by Democrats, did not run for a second term. Nixon resigned, and Gerald Ford, his successor, lost his bid for reelection. Clinton weathered the process and finished out his second term, but despite his personal popularity, he left an electorate hungering for change. “Many, including Al Gore, think that the impeachment cost Gore the election,” Paul Rosenzweig, a former senior member of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s team, told me. “So it has consequences and resonates outside the narrow four corners of impeachment.” If Congress were to impeach Trump, whatever short-term surge he might enjoy as supporters rallied to his defense, his long-term political fate would likely be sealed.

In these five ways—shifting the public’s attention to the president’s debilities, tipping the balance of power away from him, skimming off the froth of conspiratorial thinking, moving the fight to a rule-bound forum, and dealing lasting damage to his political prospects—the impeachment process has succeeded in the past. In fact, it’s the very efficacy of these past efforts that should give Congress pause; it’s a process that should be triggered only when a president’s betrayal of his basic duties requires it. But Trump’s conduct clearly meets that threshold. The only question is whether Congress will act.

Here is how impeachment would work in practice. The Constitution lays out the process clearly, and two centuries of precedent will guide Congress in its work. The House possesses the sole power of impeachment—a procedure analogous to an indictment. Traditionally, this has meant tapping a committee to summon witnesses, subpoena documents, hold hearings, and consider the evidence. The committee can then propose specific articles of impeachment to the full House. If a simple majority approves the charges, they are forwarded to the Senate. The chief justice of the United States presides over the trial; members of the House are designated to act as “managers,” or prosecuting attorneys. If two-thirds of the senators who are present vote to convict, the president is removed from office; if the vote falls short, he is not.

Although the process is fairly clear, the Founders left us only vague instructions about when to implement it. The Constitution offers a short, cryptic list of the offenses that merit the impeachment and removal of federal officials: “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The first two items are comparatively straightforward. The Constitution elsewhere specifies that treason against the United States consists “only in levying War” against the country or in giving the country’s enemies “Aid and Comfort.” As proof, it requires either the testimony of two witnesses or confession in open court. Despite the appalling looseness with which the charge of treason has been bandied about by members of Congress past and present, no federal official—much less a president—has ever been impeached for it. (Even the darkest theories of Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia seem unlikely to meet the Constitution’s strict definition of that crime.) Bribery, similarly, has been alleged only once, and against a judge, not a president.

It is the third item on the list—“high crimes and misdemeanors”—on which all presidential impeachments have hinged. If the House begins impeachment proceedings against Donald Trump, the charges will depend on this clause, but Congress will first need to decide what it means.

At the Constitutional Convention, an early draft included “treason, bribery, and corruption,” but it was shorn of that last item by the time it arrived on the floor. George Mason, of Virginia, spoke up. “Why is the provision restrained to Treason & bribery only?” he asked, according to James Madison’s notes. “Treason as defined in the Constitution will not reach many great and dangerous offences … Attempts to subvert the Constitution may not be Treason as above defined.” Mason moved to add “or maladministration.”

Madison, though, objected that “so vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate.” Gouverneur Morris further argued that “an election of every four years will prevent maladministration.” Mere incompetence or policy disputes were best dealt with by voters. But that still left Mason’s original concern, for the “many great and dangerous offences” not covered by treason or bribery. Instead of “maladministration,” he suggested, why not substitute “other high crimes & misdemeanors (agst. the State)”? The motion carried.

Constitutional lawyers have been arguing about what counts as a “high crime” or “misdemeanor” ever since. The phrase itself was borrowed from English common law, although there is no reason to suppose Mason and his colleagues were deeply familiar with its uses in that context. The Nixon impeachment spurred Charles L. Black, a Yale law professor, to write Impeachment: A Handbook, a slender volume that remains a defining work on the question.

Black makes two key points. First, he notes that as a matter of logic as well as context and precedent, not every violation of a criminal statute amounts to a “high crime” or “misdemeanor.” To apply his reasoning, some crimes—say, violating 40 U.S.C. §8103(b)(2) by willfully injuring a shrub on federal property in Washington, D.C.—cannot possibly be impeachable offenses. Conversely, a president may violate his oath of office without violating the letter of the law. A president could, for example, harness the enforcement powers of the federal government to systematically persecute his political opponents, or he could grossly neglect the duties of his office. That sort of conduct, in Black’s view, is impeachable even when it is not actually criminal.

His second point rests upon the principle of eiusdem generis—literally, “of the same kind.” As the last item in a list of three impeachable offenses, surely “high crimes and misdemeanors” shares some essential features with the first two. Black suggests that treason and bribery have in common three essential features: They are extremely serious, they stand to corrupt and subvert government and the political process, and they are self-evidently wrong to any person with a shred of honor. These, he argues, are features that a “high crime” or “misdemeanor” ought to share.

Black’s views on these points are not uncontested. Nixon’s attorneys argued that impeachment did require a crime. In 1974, before Black published his book, a report from the Justice Department split the difference, concluding that “there are persuasive grounds for arguing both the narrow view that a violation of criminal law is required and the broader view that certain non-criminal ‘political offenses’ may justify impeachment.”

John Doar, the attorney hired by the House Judiciary Committee to oversee the Nixon investigation, handed off the question of what constituted an impeachable offense to two young staffers: Bill Weld and Hillary Rodham. They determined that the answers they were seeking were to be found not in old case law, but in the public debates that raged around past impeachment efforts. The memo Weld and Rodham helped produce drew on that context and sided with Black: “High crimes and misdemeanors” need not be crimes. In the end, Weld came to believe that impeachment is a political process, aimed at determining whether a president has fallen short of the duties of his office. But that doesn’t mean it’s arbitrary. In fact, the Nixon impeachment left Weld with a renewed faith in the American system of government: “The wheels may grind slowly,” he later reflected, “but they grind pretty well.”

Some Democrats have already seen enough from the Trump administration to conclude that it has met the criteria for impeachment. In July 2017, Representative Brad Sherman of California put forward an impeachment resolution; it garnered a single co-sponsor. The next month, though, brought the white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and Trump’s defense of the “very fine people on both sides.” The billionaire activist Tom Steyer launched a petition drive calling for impeachment. A second resolution was introduced in the House that November, this time by Tennessee’s Steve Cohen, who found 17 co-sponsors. By December 2017, when Representative Al Green of Texas forced consideration of a third resolution, 58 Democrats voted in favor of continuing debate, including Jim Clyburn, the House’s third-ranking Democrat. On the first day of the new Congress in January, Sherman reintroduced his resolution.

These efforts are exercises in political messaging, not serious attempts to tackle the question of impeachment. They invert the process, offering lists of charges for the House to consider, rather than asking the House to consider what charges may be justified. The House should instead approve a resolution authorizing an impeachment inquiry and allocating the staff, funding, and other resources necessary to pursue it, as the resolution that initiated the proceedings against Richard Nixon did.

Still, the resolutions proposed so far offer a valuable glimpse at the issues House Democrats are likely to pursue in such an inquiry. Some have made a general case that Trump has done violence to American values—Green’s stated that Trump “has betrayed his trust as President … to the manifest injury of the people of the United States”—but others have claimed specific violations of statutes or constitutional provisions. Both types of allegations may turn out to be important.

Despite the consensus of constitutional scholars that impeachable offenses need not be crimes, Congress has generally preferred to vote on articles that allege criminal acts. More than a third of representatives, and an outright majority of senators, hold law degrees; they think like lawyers. Democrats are thus focused on campaign-finance regulations, obstruction of justice, tax laws, money-laundering rules, proscriptions on bribing foreign officials, and the Constitution’s two emoluments clauses, which bar the president from accepting gifts from state or foreign governments.

They have studiously avoided, however, the primary area of public fascination when it comes to Trump’s alleged misdeeds: whether the president or his campaign colluded with Russia in the 2016 election. Lawmakers are clearly wary of bringing charges that could bear on Robert Mueller’s report, lest they interfere with an ongoing investigation that they hope will somehow force Trump from office. “It all depends on what we learn from hearings and from the Mueller investigation,” Representative Cohen told me. But the highly anticipated Mueller report is unlikely to provide the denouement lawmakers are seeking. Whether a president can be impeached for acts committed prior to assuming office is an unsettled question. As Trump himself never tires of pointing out, collusion with Russia is not itself a crime. And even if Mueller produces a singularly damning report, one presenting evidence that the president himself has committed criminal acts, he cannot indict the president—at least according to current Justice Department guidelines. Congress will have to decide what to do about it.

Once the House authorizes an impeachment inquiry, the committee must distill the evidence of Trump’s alleged crimes into articles capable of garnering a majority vote in that chamber. But that’s just the first challenge. To remove Trump from office, the House managers will then have to persuade the Senate to vote to convict the president. When the articles of impeachment are filed with the Senate, where the president will be tried, each article will be considered and voted on individually.

And then, suddenly, the members of the United States Senate will be forced to answer a question that many have long evaded: Is the president fit to continue in office? There will be no press aides to hide behind, no elevators into which they can duck. Some Democrats have already made their opinions clear. Others will have to decide whether to vote to remove a president backed by a majority of their constituents. For Republicans, the choice will be even harder.

This is where the dual nature of impeachment as both a legal and a political process comes into sharpest focus. The Founders worried about electing a president who lacked character or a sense of honor, but Americans have long since lost the moral vocabulary to articulate such concerns explicitly, preferring to look instead for demonstrable violations of rules that illuminate underlying character flaws. It is Trump’s unfitness for office that necessitates impeachment; his attacks on American democracy are plainly evident, and should be sufficient. But some Republican senators may continue to dismiss the more sweeping claims against the president, particularly where no statutory crimes attach. And so the strength of the evidence supporting narrower charges such as obstruction of justice and campaign-finance violations may ultimately determine his fate. If the committee can substantiate these charges, it will place even the most reluctant senators in a bind. When the moment finally comes to cast their vote, and the world is watching, how many will acquit the president of things he has clearly done?

The closest the senate has ever come to removing a president was in 1868, after Andrew Johnson was impeached on 11 counts. Remembered today as a lamentable exercise in hyper-partisanship, in fact Johnson’s impeachment functioned as the Founders had intended, sparing the country from the further depredations of a president who had betrayed his most basic responsibilities. We need to recover the real story of Johnson’s impeachment, because it offers the best evidence that the current president, too, must be impeached.

The case before the United States in 1868 bears striking similarities to the case before the country now—and no president in history more resembles the 45th than the 17th. “The president of the United States,” E. P. Whipple wrote in this magazine in 1866, “has so singular a combination of defects for the office of a constitutional magistrate, that he could have obtained the opportunity to misrule the nation only by a visitation of Providence. Insincere as well as stubborn, cunning as well as unreasonable, vain as well as ill-tempered, greedy of popularity as well as arbitrary in disposition, veering in his mind as well as fixed in his will, he unites in his character the seemingly opposite qualities of demagogue and autocrat.” Johnson, he continued, was “egotistic to the point of mental disease” and had become “the prey of intriguers and sycophants.”

Whipple was among Johnson’s more verbose critics, but hardly the most scathing. A remarkable number of Americans looked at the president and saw a man grossly unfit for office. Johnson, a Democrat from a Civil War border state, had been tapped by Lincoln in 1864 to join him on a national-unity ticket. A fierce opponent of the slaveholding elite and a self-styled champion of the white yeomanry, Johnson spoke to voters skeptical of the Republican Party’s progressive agenda. He horrified much of the East Coast establishment, but his raw, even profane style appealed to many voters. The National Union Party, seeking the destruction of slavery and the Confederacy, swept to victory.

No one ever thought Johnson would be president. Then, in 1865, Booth’s bullet put him in office. The end of the war exposed how different Johnson’s own agenda was from the policies favored by Lincoln. Johnson wanted to reintegrate the South into the Union as swiftly as possible, devoid of slavery but otherwise little changed. Most congressional Republicans, by contrast, wanted to seize the moment to build a new social order in the South, enshrining equality and protecting civil rights. Johnson sought to restore America as it had been, while the Republicans hoped to make it more perfect.

The two visions were irreconcilable. As the feud deepened, each side pushed its commitments to their logical extremes. Congressional Republicans approved the Fourteenth Amendment, voted to enlarge the role of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and passed the Civil Rights Act. Taken together, these measures established the equality of Americans before the law and, for the first time, made its preservation a federal concern. They amounted to nothing less than a social revolution, a promise of an America that belonged to all Americans, not just to white men.

[From the archives: W. E. B. Du Bois on the Freedmen’s Bureau]

Johnson and his supporters found this intolerable. In federal efforts to establish racial equality, they saw antiwhite discrimination. Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act, insisting that “the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race.” For the first time in American history, Congress overrode a veto to pass a major piece of legislation. Three months later, he vetoed the renewal of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, complaining that its plan to distribute land to former slaves constituted “discrimination” that would establish a “favored class of citizens.” Congress again overrode his veto. That set up an unprecedented situation, as the president was asked to administer laws he had tried to block. Instead of the promised peace, the nation found itself gripped by an accelerating crisis.

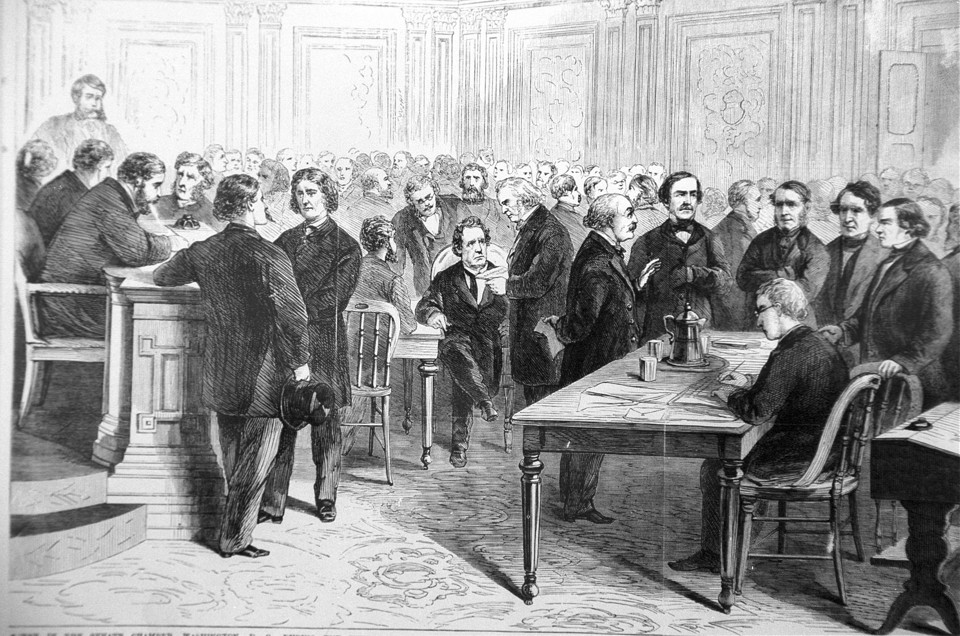

credit: Library of Congress / Getty // The Atlantic

The question facing Congress, and the public, was this: What do you do with a president whose every utterance and act seems to undermine the Constitution he is sworn to uphold? At first, Republicans pursued the standard mix of legislative remedies—holding hearings and passing bills designed to strip the president of certain powers. Many members of Johnson’s Cabinet worked with their congressional counterparts to constrain the president. Johnson began to see conspiracies around every corner. He moved to purge the bureaucracy of his opponents, denouncing the “blood-suckers and cormorants” who frustrated his desires.

It was the campaign of white-nationalist terror that raged through the spring and summer of 1866 that persuaded many Republicans they could not allow Johnson to remain in office. In Tennessee, where Johnson had until the year before served as military governor, a white mob opposed to black equality rampaged through the streets of Memphis in May, slaughtering dozens of people as it went. July brought a second massacre, this one in New Orleans, where efforts to enfranchise black voters sparked a riot. A mob filled with police, firemen, armed youths, and Confederate veterans shot, stabbed, bludgeoned, and mutilated dozens, many of them black veterans of the Union Army. Johnson chose not to suppress the violence, using fear of disorder to build a constituency more loyal to him than to either party.

Congress opened impeachment hearings. The process unfolded in fits and starts over the next year and a half, as Johnson’s congressional opponents searched vainly for some charge that could gain the support of a majority of the House. Then Johnson handed it to them by firing his secretary of war, defying a law passed, in part, to stop him from undermining Reconstruction. The House passed 11 articles of impeachment, forcing Johnson to stand trial before the Senate. But the effort fell short by a single vote.

When Johnson’s supporters learned that he had been spared, they were ecstatic. In Milwaukee, they careened down the street in a wagon, shouting for Johnson and liberty, sharing a keg of beer. In Boston and in Hartford, Connecticut, they fired 100‑gun salutes; in Dearborn, Michigan, they settled for 19 guns and bonfires. “We have stood for the last few months upon the verge of a precipice, a dark abyss of anarchy yawning at our feet,” the Maryland Democrat Stevenson Archer said, sketching an alternative result whereby “dark-skinned fiends and white-faced, white-livered vampires might rule and riot on the little blood they could still suck out by fastening on helpless throats.”

But the euphoria proved short-lived. The New York Times urged Johnson’s supporters to look at the bigger picture: “Congress has assumed control of the whole matter of reconstruction, and will assert and exercise it.” Any effort to wrest control back from the House and Senate was held in check by the specter of another impeachment, which haunted Johnson’s remaining months in office. The Democrats took up Johnson’s political cause; their convention theme in 1868 was “This Is a White Man’s Country; Let White Men Rule.” But when the politically damaged Johnson made a bid for the Democratic nomination—“Why should they not take me up?”—he was refused. Ulysses S. Grant won on the Republican ticket, and threw the full force of the Army behind the project of Reconstruction. Johnson went home to Tennessee.

If the goal of impeachment was to frustrate Johnson’s efforts to make America a white man’s country again, it was an unqualified success. Instead of being remembered as a triumph, however, in the years that followed, it was memorialized as a failure. Defending the impeachment on substantive grounds required believing that all people born in the United States—white and black alike—deserved the same civil liberties. And a decade later, America changed its mind about that, abandoning the project of Reconstruction and reneging on its promise of civil rights for African Americans. Johnson had said he was fighting to preserve a “white man’s government,” and for the next century, that’s what the country largely had. Robbed of its animating force, the bill of particulars against Johnson began to seem hollow, petty, and misguided. How could it have been proper to impeach a president for undermining the Constitution’s guarantee of equality, when the nation as a whole had subsequently done the same?

The chorus of experts who now present Johnson’s impeachment as an exercise in raw partisanship are not learning from history but, rather, erasing it. Johnson used his office to deny the millions freed from bondage the equality that God had given them and that the Constitution guaranteed. To deny the justice of Johnson’s impeachment is to affirm the justice of his acts. If his impeachment was partisan, it was because one party had been formed to defend the freedom of man, and the other had not yet reconciled itself to that proposition.

The senators who voted against convicting Johnson insisted that they were standing on principle and upholding the Constitution. Yet some of the same lawmakers who expended so much effort defending the prerogatives of the presidency simultaneously turned a blind eye to the gross civil-rights violations that pervaded the South; their deep concern for constitutional niceties with respect to the president gave way to willful indifference when blacks were the ones who were systematically and violently deprived of their rights. It was a bitter irony: The impeachment proceedings were greeted with alarm by those who feared they would destroy the Constitution. In the end, though, it was the regular process of government that eventually ratified Jim Crow, the most outrageous abrogation of constitutional protections in the nation’s history. Impeachment drew the United States closer to living up to its ideals, if only fleetingly, by rallying the public against Johnson’s assault on the Constitution.

Today, the United States once more confronts a president who seems to care for only some of the people he represents, who promises his supporters that he can roll back the tide of diversity, who challenges the rule of law, and who regards constitutional rights and liberties as disposable. Congress must again decide whether the greater risk lies in executing the Constitution as it was written, or in deferring to voters to do what it cannot muster the courage to do itself. The gravest danger facing the country is not a Congress that seeks to measure the president against his oath—it is a president who fails to measure up to that solemn promise.

[Yoni Appelbaum is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where he oversees the Ideas section.

Appelbaum is a social and cultural historian of the United States. Before joining The Atlantic, he was a lecturer on history and literature at Harvard University. He previously taught at Babson College and at Brandeis University, where he received his Ph.D. in American history.]