What’s Behind the Teacher Strikes: Unions Focus on Social Justice, Not Just Salaries

What's behind the teacher strikes: Unions focus on social justice, not just salaries

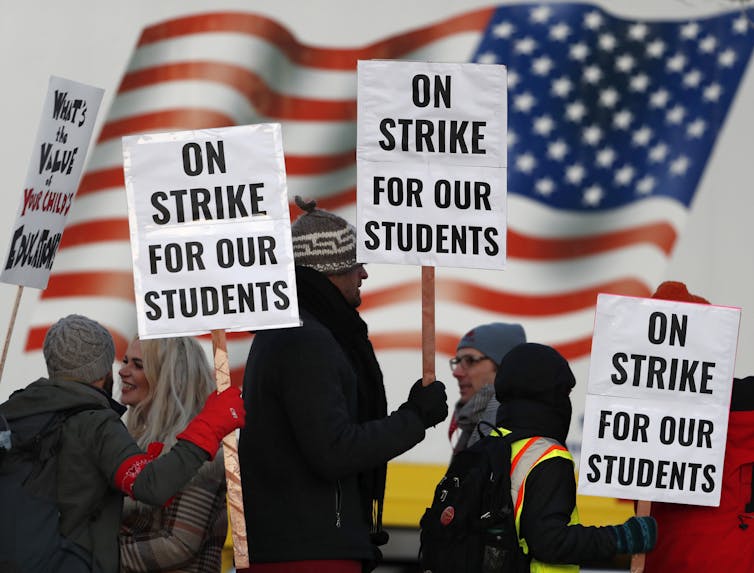

Striking teachers are increasingly casting their struggle as being part of a broader struggle for social justice. David Zalubowski/AP

For the past few years I’ve been studying teacher unions and teachers strikes throughout the Americas. My research has taken me from the Mexican state of Oaxaca – where teacher protests in 2006 led to both violent repression and a broad-based social movement for direct democracy – to the streets of São Paulo, Brazil, to coal-mining towns in West Virginia.

I’ve learned that certain conditions prompt teacher unions to adopt new forms of activism and take up broader issues of social justice that go beyond how much teachers are paid.

Now is such a time in the United States.

Factors driving the strikes

The teacher strike that began Feb. 21 in Oakland, California, is just the latest example in a wave of teacher strikes that have swept the country over the past year.

In my view as a researcher who deals with issues of education and labor, the current teacher strike wave in the United States is the result of three factors.

First is the acceleration of market-based education reforms, including the expansion of charter schools.

Second is networks of teacher activists organizing and transforming their unions to focus on broader social issues.

Third is the framing of teacher union action as part of the struggle for racial justice.

These factors have led teacher unions to form alliances with community organizations, enlist students and parents to join the activism, and speak out against efforts to expand charter schools and privatization.

Inspired by Occupy

Let’s look at how these three factors played out in Oakland, starting several years ago.

As I learned through interviews, teacher activists in Oakland drew inspiration from the Occupy movement in 2011. They helped occupy a local elementary school to protest its closing, and eventually created a union caucus called Classroom Struggle with a couple dozen teachers to promote more social justice issues. Then, last spring, these teacher activists created a slate, in alliance with African-American teacher and organizer Keith Brown, and won the leadership of the Oakland Education Association. Since taking office on July 1, 2018, this new union leadership – inspired by the successful strikes in West Virgina, Arizona and Los Angeles – have been preparing for a strike.

The conditions that led to the Oakland strike are similar to those that led to strikes in other cities earlier this year, such as Los Angeles.

For instance, public education in Oakland has been defunded and the city, much like Los Angeles, is experiencing charter school expansion that teachers say is taking money away from public schools. One recent report found that charter schools take US$57.3 million a year from public schools in Oakland.

Teacher union actions in Oakland also mirror tactics and strategies that unions have used in other cities. For instance, Oakland teacher union leaders have enlisted the help of student and community groups and focused on racial justice.

Teacher unions are enlisting students to help support their strikes. David Zalubowski/AP

All these actions have transformed the Oakland Education Association – and many other teachers’ unions across the country – into leaders of a social movement that has the potential of redefining public education, the labor movement and American politics.

Much of the media attention on teacher strikes has focused on the economic reasons for the strikes, such as low teacher salaries, rising health care costs and aging textbooks. But there are important historical factors at play.

Historically, teachers’ unions have not led social, racial and economic justice movements. But there are some exceptions. Those exceptions include teacher unionists’ critique of authoritarianism in Mexico in the 1980s and 1990s; teachers’ participation in the movement for a return to democracy in Brazil in the late 1970s; and, in the United States, the participation of many teacher union leaders in the civil rights activism of the 1950s and 1960s.

However, it is also important to note that during the 1960s, many teachers in the United States also found themselves at odds with communities of color. Perhaps this is best exemplified by the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville Strike, when the United Federation of Teachers rallied against black community control of schools.

New alliances

Today’s teacher activists have bridged the divide between teacher unions and communities of color. For instance, between 2010 and 2012, teacher activists from Chicago’s Caucus of Rank and File Educators, or CORE, aligned with other community groups to organize against school closings in black and Hispanic neighborhoods. CORE also supported parents and students occupying an elementary school to prevent its closure. Their rallying call – “Schools that Chicago Students Deserve” – included demands for reduced class size and other things related to classroom conditions.

In Los Angeles, activists embraced this social movement approach to union activism, fighting for the “Schools that LA Students Deserve.” In 2014, the Los Angeles activists created a new caucus, Union Power, winning the elections and immediately hiring dozens of new organizers to help build towards a strike. They worked in alliance with dozens of community organizations.

The Black Lives Matter movement fueled energy into a new student movement, called Students Deserve, directly supported by the union leadership. The six-day LA strike in early 2019 represented, more than anything else, an explicit racial justice struggle. The LA strike also called into question claims by the charter and voucher movements that school choice policies represent the best path to social mobility for children from poor communities of color.

Teacher unions are not always – and not often – the leaders of broader social justice movements. Now that’s changing due to a new generation of union activists who see their struggle as part of the fight for equitable resources for the communities in which they teach.![]()

Rebecca Tarlau, Assistant Professor of Education and of Labor and Employment Relations, Pennsylvania State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.