Frida Kahlo: Communist, Feminist, Global Commodity

Long before the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo was a global commodity, she was a communist. As a precocious teenager, she joined the Communist Party of Mexico and in her twenties, she led union rallies with her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera. It is said that she decorated her headboard with images of Marx, Engels and Lenin. In 1954, 11 days before she died from an arterial blood clot at age 47, Kahlo marched in a protest against U.S. involvement in the coup that deposed leftist president Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán in Guatemala. At her funeral, a red flag bearing a sickle and hammer was draped over her casket. “I’m more and more convinced it’s only through communism that we can become human,” she wrote in her diary during an extended stay in New York and Detroit in the 1930s. Kahlo’s radical politics built on her experiences as a mixed-race, disabled, bisexual, polyamorous, Jewish feminist who suffered from chronic pain, which she alleviated with tequila. Of her condition, she wrote, “I am not sick. I am broken.”

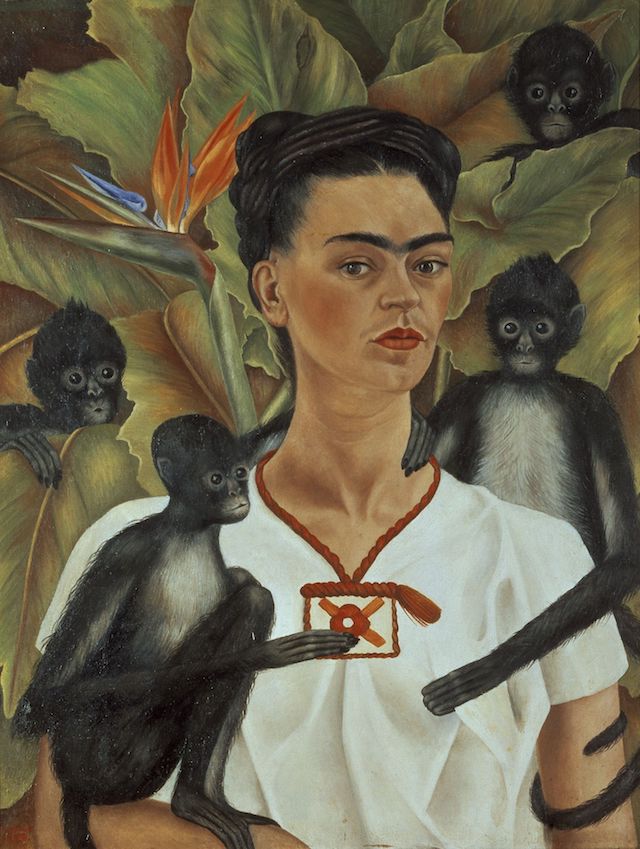

The Brooklyn Museum’s blowout exhibition “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” the largest show dedicated to the artist in U.S. history, is a testament to Kahlo’s political and artistic life in all of its complexities and contradictions. Over 350 objects — from her eyebrow pencils and her favored pink lipstick to her Oaxacan ceramics and shawls — overshadow less than 15 paintings. The exhibition does not seek to challenge Kahlo’s rise to global stardom as a massively profitable cultural commodity — Bank of America, Delta Airlines and Revlon, Kahlo’s preferred lipstick brand, sponsored the exhibition — but for the most part, corporate sponsorship does not distract from Kahlo’s political and aesthetic vision.

The exhibition begins with a series of videos and photographs documenting the Mexico that Kahlo grew up in during the Revolution and its aftermath. Kahlo was born in 1907 — when Porfirio Díaz and his aristocratic regime still ruled Mexico, but later she fudged the dates, claiming 1910 as the year of her birth in alignment with the start of the Mexican Revolution. She grew up in a lower-middle-class household, the third of four daughters, in Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán. Her Jewish father, a photographer, immigrated to Mexico from Germany in 1892, and her mother — of Spanish and indigenous P’urhépecha descent — was from Oaxaca. A series of black and white silver gelatin prints taken by her father depict Kahlo posing for her father at a young age wearing the stoic, inscrutable expression that she would return to in her self-portraits later in life.

Collection of Museo Frida Kahlo.

The photos progress from Kahlo at age two to her early adulthood in the post-Revolution years, when progressive political reform and a series of public works programs swept the nation. We see Kahlo at a march for the Union of Mexican Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors; Kahlo dressed as a communist comrade with her classmates at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria; Kahlo with braids and a rebozo shawl talking to peasants in the countryside; Kahlo in a wheelchair at a protest of the CIA’s involvement in Guatemala in 1954.

In Kahlo’s social circles, the appeal of socialism went hand-in-hand with the rise of a resurgent Mexican nationalism. The aftermath of the Revolution led to a period of national identity building, spearheaded by the minister of public education, José Vasconcelos — and joined by artists like Kahlo and her husband, Rivera. The movement celebrated Mexico’s multi-ethnic heritage, or mestizaje, in particular, by appropriating indigenous culture from southern Mexico for an identity that could unite all Mexicans — white, brown and mestizo into a “cosmic race.” In one gallery, curators recreate Kahlo’s Mexico City home, the Casa Azul, with displays of pre-Colombian ceramics, vases and sculptures dating as far back as 200 B.C.E, as well as votive paintings and folk art from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

Kahlo took political, aesthetic and sartorial inspiration from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec — Mexico’s narrowest point, which connects the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf. It’s where Kahlo’s mother had roots, though Kahlo herself never visited. An extensive set of cases display Kahlo’s wardrobe drawn from matriarchal Tehuana culture — lace headdresses, embroidered floral skirts, woven shawls, cotton and silk tunics in magenta, golden yellow, and azure — at times with Chinese and European flourishes. Another section is dedicated to the orthopedic corsets, prosthetic legs and plaster casts (some painted with the communist hammer and sickle) that she wore beneath the colorful dresses to support her injured spine. “Appearances can be deceiving,” a nearby charcoal sketch is titled, revealing the medical devices hidden beneath the elaborate costume. (The exhibition was named after the 1946 drawing).

The show reminds viewers that for much of Kahlo’s life, Diego Rivera and his sweeping murals depicting agrarian reform and campesino struggles overshadowed Kahlo and her self-portraits. A 1933 article from the Detroit News, printed on one gallery wall, shows Kahlo painting in her studio with the accompanying headline: “Wife of Master Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art.” A demeaning Time Magazine review from 1938 of a Kahlo exhibition in Manhattan reads, “Too shy to show her work before, black-browed little Frida has been painting since 1926, when an automobile smashup put her in a plaster cast, ‘bored as hell.’”

The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and the Vergel Foundation.

When I visited the show, I overheard several young women quietly remarking that they always considered Kahlo a more compelling artist than her husband Rivera. Indeed, today — Kahlo stands as an icon for all sorts of marginalized groups as well as cultural elites. Unlike her husband, her reach extends far beyond her paintings into the worlds of high fashion, queer and Chicano identity politics and both grassroots and corporate feminism. (As one egregious example, Britain’s Prime Minister Theresa May wore a Frida Kahlo bracelet to give a speech at a Conservative Party conference in 2017.) For better or worse, the expansive Frida Kahlo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum leans into all of these narratives at once, allowing the viewer to take home what they will.

The exhibition Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving runs through May 12 at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York 11238-6052. Information on the exhibit, museum hours, ticket prices, travel directions are available HERE.

[Lauren Kaori Gurley is an editor at the North American Congress on Latin America and a graduate student at New York University. She is a contributing writer to Rural America In These Times, previously she contributed to the American Prospect, Quartz, and the South Side Weekly. She lives in Brooklyn, New York. You can follow her on Twitter: @laurenkgurley.]

The Indypendent describes itself as “a free paper for free people.” For information on donating, go HERE.