Cities and States Are Modeling What a Green New Deal Could Look Like

Lawmakers in Washington, D.C., have spent the past two months engaged in a war of words over the Green New Deal resolution. Many argue its ambitious goals aren’t feasible within the short timeframe it lays out. Others say there’s simply no alternative.

While they’ve been sparring, however, cities and states across the country have been moving forward with their own ambitious plans, showing how elements of the radical proposal could take shape at a local level.

“I think at the state and local level, we’ve got the capacity to do it,” Alan Webber, mayor of Santa Fe, New Mexico, told ThinkProgress.

Webber’s city has been moving swiftly on climate action over the past few years. Part of that is necessity: New Mexico already suffers from water shortages, something the 2018 National Climate Assessment (NCA) warns will only grow worse in the Southwestas climate change intensifies droughts. With no time to waste, Santa Fe is jumping in head first.

“We are on land that belongs to the Pueblo,” Webber said, noting that indigenous communities in the area have paved the way for the “sustainable life” Santa Fe is now pursuing.

Last November, Santa Fe adopted a sustainability plan putting the city on the road to carbon neutrality by 2040. That’s 10 years later than the Green New Deal proposes, but it’s still a rapid timeline. And it’s one that includes a host of factors — moving to renewable energy, upgrading buildings and street lighting, water conservation, and local food production, in addition to more run-of-the-mill actions like recycling.

“It’s a comprehensive approach to having a sustainability roadmap,” said Webber.

What is unfolding in Santa Fe is an accelerated version of the conversation taking place on the national level. Once a topic pushed to the side by Republicans and Democrats alike, climate change has been catapulted to the top of the political agenda in recent months. After two years of deadly wildfires and hurricanes across the country, polling shows that most Americans accept the science behind climate change and that many feel it is already impacting their lives directly. And they are demanding action.

Congressional newcomers like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), joined by activist groups like the youth-led Sunrise Movement, have led the charge. In February, Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) introduced the Green New Deal resolution, a blueprint for overhauling the entire U.S. economy and transitioning to emissions-neutral energy sources within a decade.

Short on specifics, the resolution is meant to serve as an aspirational blueprint for eventual legislation in Congress that would emphasize rapidly transitioning the United States away from fossil fuels, in line with the latest science, all while investing in job creation, education, and health care.

Ambitious climate legislation akin to the Green New Deal faces gridlock in Congress and staunch opposition from the White House, making it essentially a non-starter right now. But that isn’t true of cities and states.

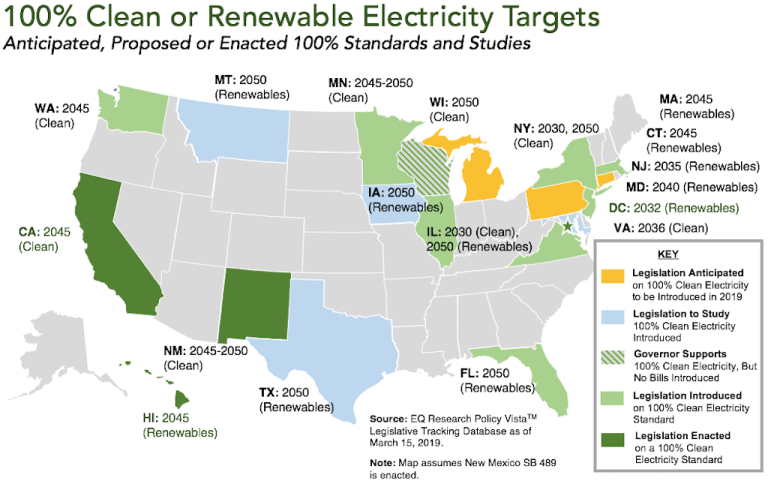

As of March, at least 19 states are considering or have already set 100 percent clean or renewable electricity targets, according to EQ Research, a policy group that works on issues like energy efficiency and renewables. Not all of those efforts resemble the full spectrum of changes called for under the Green New Deal, however, as they focus predominately on electricity goals. But several of the plans incorporate language about jobs and social justice, with some directly referencing the Green New Deal as a source of inspiration. That’s significant because, without federal support, ground-up implementation could be how the Green New Deal ultimately becomes a reality.

Ambitious energy targets alone are notable in several areas. Hawaii and California have enacted legislation to hit a 100 percent clean or renewable electricity target by 2045, while Washington, D.C., is aiming for 2032. And already this year, 10 more states have followed suit, introducing their own legislation to reach a clean electricity standard by 2050 or earlier.

CREDIT: EQ RESEARCH

This marks a dramatic change of pace compared to a few years ago, according to Ben Inskeep, a research analyst with EQ Research. “We definitely do see a lot of examples at the state level where we see [decarbonization targets] ratcheting up,” Inskeep told ThinkProgress.

According to an alarming U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released last fall, the world only has around a decade left before crossing a dangerous global warming threshold. Reaching 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming above pre-industrial levels would, the report warns, mean devastating climate impacts on a scale the world is not prepared to address. This is why the Green New Deal resolution emphasizes the importance of serious, widespread action by 2030, in keeping with established climate science.

Many cities and states, however, are operating within the 2050 deadline, which proponents of the Green New Deal may view as unambitious. But Inskeep says such criticism might be missing the point. The fact that local officials are announcing significant emissions reduction goals by 2050 is remarkable, he said, arguing the chief takeaway is less about the timeframe and more about growing momentum.

“Some folks might say 2050 is too far in the future… down the road,” he said. “ certainly none of us were having this conversation even three years ago… we’re seeing already that ratcheting up.”

There was a time when 2050 seemed like an impractical goal, Inskeep explained. Now, it’s relatively average for most middle-of-the-road ambitions, viewed as achievable in part thanks to the rapidly-dropping costs of wind and solar power, in addition to advancements in technology. If lawmakers now see 2050 as an achievable deadline, that indicates just how much policymakers and officials have adjusted their expectations, and perhaps could ramp up ambitions even more down the road.

“A few years ago, it would’ve been very surprising to see any kind of 100 percent proposal introduced… now, we have 10 more states introducing legislation… that’s a tremendous growth,” he said.

In Santa Fe, action to implement the city’s sustainability plan is already in full swing. Last month, the city sold the state’s first-ever “green bonds,” which allow investors to finance environmental projects. That sale is translating to a $15 million city wastewater upgrade, which includes the construction of an anaerobic digester.

Through the new system, microorganisms will break down biodegradable waste from the city. In the process, they will reduce emissions and generate clean energy. With the help of solar power and the digester, almost 95 percent of the plant’s power will be produced onsite. The energy savings are projected to eliminate some 3,100 metric tons of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of taking nearly 750 cars off of the road.

Such projects are a good example of how cities can be innovative as they seek to lower their emissions. But the city’s mayor is thinking bigger.

“We tend to think of policies in silos but people don’t live in silos, they live their lives,” Webber said. In addition to committing Santa Fe to carbon neutrality, he’s also interested in job creation through renewable energy, something the Green New Deal emphasizes. He moreover sees other social efforts as being key components of any long-term plan, like protecting the city’s undocumented members, as well as low-income communities and people of color impacted by pollution.

“There’s a renewable energy piece, a transportation piece, a land-use planning piece, a social equity piece, a jobs and inclusivity piece,” he said.

Santa Fe is part of a larger story unfolding in New Mexico. On March 22, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) signed the Energy Transition Act, which would require the state’s electricity grid to be completely carbon-free by 2045. It also earmarks funds for communities impacted by the transition away from fossil fuels, including coal workers.

“This is a state that is not in climate denial,” the governor declared. “We are clear that we have basically a decade to begin to turn things around and New Mexico needs and will do its part.”

The legislation comes as New Mexico struggles with hard choices. The state is a poor one, and it is also a leading fossil fuel producer. The Permian Basin, which straddles West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, is the leading oil and gas reserve in the country. And more than half of New Mexico’s electricity comes from coal.

Lujan Grisham has said she wants to work with the fossil fuel industry to reduce emissions, but environmental advocates worry that flies in the face of New Mexico’s lofty climate goals.

The Santa Fe-based New Energy Economy (NEE), which advocates for addressing climate change and shifting away from fossil fuels, has been critical of the Energy Transition Act. The environmental group has argued that the law provides too much assistance to Public Service Company of New Mexico, or PNM, the utility operator behind the failing San Juan Generating Station coal plant. According to NEE, the law amounts to a polluter “bailout” and was passed without the support of a number of tribal leaders.

Others feel differently. Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez backed the law, as did many other stakeholders and a slew of environmental groups. That split in support indicates the challenges that others might also encounter as they look to pass similar legislation.

Efforts in New Mexico are nonetheless notable in the components they bring together. Namely, they go beyond advocating for a shift away from fossil fuels, and also work to grow jobs and protect impacted communities. That’s language that has made the Green New Deal resolution so popular for some and so divisive for others. But such small-scale efforts will also be a test of whether a bigger and bolder endeavor might succeed.

Some state proposals are in the early development stage. In Rhode Island, a tiny state threatened by sea level rise and overly vulnerable to financial crisis, the state is looking to begin researching its own version of a Green New Deal. Historically, Rhode Island has been among the first states to fall into recessions and the last to leave them — something a stimulus centering green jobs could help avoid.

Others are further along. Last month, Illinois introduced the Clean Energy Jobs Act, which would push hard for job expansion as the state shifts away from fossil fuels. It also emphasizes increased solar distribution in vulnerable communities and the importance of creating energy-related jobs in low-income and pollution-impacted areas.

And many local leaders are leaning into the language popularized by Ocasio-Cortez and young activists. Los Angeles city council members have used the language of the Green New Deal to push for an end to natural gas generation in the city. And in Holyoke, Massachusetts, the city’s shift from coal to solar power has been similarly marketed by activists and officials.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) of New York also wasted no time in labeling the climate components of the state’s 2019 executive budget as a Green New Deal. That budget seeks to put New York on the road to “economy-wide carbon neutrality” by 2040, while ensuring a “just transition to clean energy.”

New York has already banned fracking, committed to phasing out coal by 2020, and set a 50 percent renewable power target by 2030. And thanks to the potential of offshore wind, state officials are feeling confident about New York’s energy transition. They’re also hopeful that the state can be a model for others, said Alicia Barton, president and chief executive of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA).

“New York is very focused on developing a plan for economy-wide decarbonization that we can deliver on as we progress toward achieving the state’s nation-leading goals,” Barton told ThinkProgress. She said she hopes the state’s “leadership” will help national efforts by “driving the clean energy transition faster than anyone thought.”

City and state-level efforts remain different from federal action in that they are much smaller scale and thus easier to implement. However, virtually every official who spoke to ThinkProgress indicated that assistance from Congress and the White House would help, either with funding or with general guidance. But the polarized nature of Washington is proving challenging in that regard, as is evident by the Green New Deal’s failure to gain bipartisan support.

Webber, of Santa Fe, sees an opening there. “I think particularly with the federal government frozen in so many ways, the level of engagement is shifting to the cities and the states,” he said.

And in some ways, they may be better equipped to address some problems. Cities and states, Webber says, are “closer to the problem and also closer to the people affected by the issues, like closing down a coal mine.”

While he noted that things change nationally and globally at a swift pace, Webber retains the view that what happens in cities like Santa Fe has the potential to offer a path forward to others.

“I think the pieces all fit together in terms of what we’re trying to achieve — a city that has a very deep commitment to sustainability and livability, [that is] guided by a set of values,” he said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=782-Gq0CzxM

E.A. Crunden covers climate policy. Texpat. She/her, they/them, or no pronouns. Get in touch: ecrunden@thinkprogress.org.

ThinkProgress has launched a membership program to help fund our work. As a nonprofit we depend in large part on donations. If just a small percentage of our readers chips in a few dollars each month, we’ll be able to do more to hold the administration and their allies accountable and to provide you with thought-provoking journalism. JOIN US!