The Doctor’s Strike That Nearly Killed Canada’s Medicare-for-All Plan, Explained

A few weeks ago, New York Times columnist David Brooks anointed Medicare-for-all as the “impossible dream.”

“There is no plausible route from here to there,” he declared.

The argument that Brooks outlines makes sense. There are many interests lined up against a single-payer system in the United States. Hospitals don’t want it. Doctors don’t want it. And insurers definitely don’t want it, given that it would be a death knell for their industry.

Transitioning to a Medicare-for-all system would no doubt be really, really hard. It would require unwinding a multi-billion dollar health insurance industry that employs about a half-million Americans. Private health insurers exist at the core of the American economy; as the New York Times pointed out this weekend, insurers’ stocks are a staple of the mutual funds that often make up our retirement accounts.

Both the Medicare-for-all plans I’ve read and the interviews I’ve done with their authors in Congress suggest that more prep work is needed for the massive upheaval that would come with eliminating private insurance.

Building a Medicare-for-all system would be hard, but there is nothing about America that makes single-payer an impossibility. The experience of other health care systems suggests that, with enough political will, single-payer advocates can overcome the exact type of opposition Brooks discusses.

There is no better place to learn this lesson than from our neighbors to the North in Canada. Brooks cites Canada as a country where people “love their single-payer health care system.” Brooks brings up Canada as an example of a country that is different from ours, one where there is widespread acceptance of more government involvement in health care.

But it wasn’t always like that. Canada experienced massive upheaval and protest when its single-payer system launched in 1962. Back then, Canadian single-payer opponents were making the exact same arguments against the program as American single-payer opponents do today: that it was too much government in medicine, that physicians would no longer be able to practice medicine in the way they saw fit. The doctors even went on strike (for more than three weeks) when the system launched.

“It was a very close call,” says Greg Marchildon, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies the history of Canadian health care. “The doctors were totally against it, half the population was totally against it and the other half were totally for it. It could have gone either way.”

The history of Canadian health care, it turns out, can actually offer a glimpse of what America’s future could look like if a committed government tried to enact Medicare-for-all.

When Canada launched single-payer, thousands of doctors went on strike

In 1960, the Canadian province of Saskatchewan elected a socialist premier named Tommy Douglas who had campaigned on a promise to bring universal insurance to his province. (Incidentally — just because I couldn’t leave this fact out — Tommy Douglas turns out to be Kiefer Sutherland’s grandfather. Who knew!)

Douglas followed through on that promise: In late 1961, his government passed the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Act. The province already had government-sponsored hospital insurance, but this new bill would layer on a plan to cover doctor visits.

There was no comparable insurance scheme for doctor visits, which meant that patients could still end up with a significant bill from the doctor who saw them in the hospital.

“Doctors continued to bill independently,” Marchildon, the historian, says. “If they worked in the hospital, the patient would end up getting a bill for that.”

Some doctors did participate in smaller, publicly-run health plans that cities offered, but many found it more lucrative to accept private payments from wealthier clients.

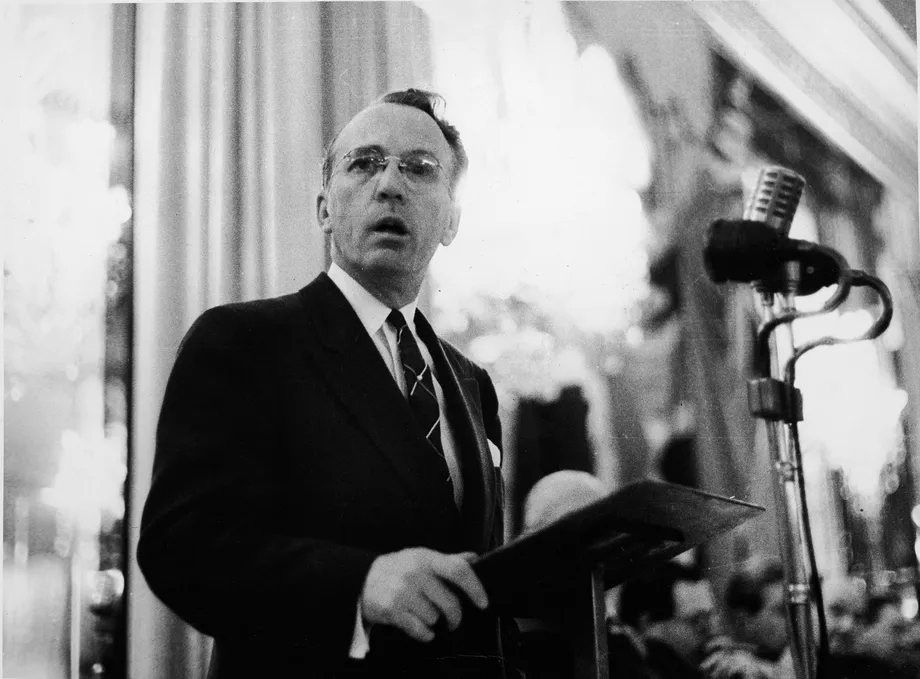

Scottish-born Canadian Baptist minister and politician Tommy Douglas set up the first socialist government in North America and introduced national health care to Canada. Express Newspapers/Getty Images

Canadian doctors were not pleased with the new plan, which would move all Saskatchewan residents into a public health program. The Canadian Medical Association denounced the law, as did the provincial medical association. They produced pamphlets (like this one here) that said things like “Political medicine is the type of medicine this Province can expect if government—any government, controls you and your doctor. It would mean red tape, high costs and inferior medical care.”

The arguments doctors made back then sound an awful lot like the ones we hear against single-payer today. “It places the control of medicine in the hands of the government and its appointees,” one doctor warned at a public forum. “This we could never accept.”

But Douglas refused to back down. On July 1, 1962, Saskatchewan launched North America’s first universal, government-run health insurance scheme for hospital and doctor visits.

That same day, Saskatchewan’s doctors went on strike.

Groups sprung up around Saskatchewan to support the striking doctors known as KODs, which stood for “Keep our doctors.” They organized a rally at the provincial capital, and thousands attended. Some of the participants carried small effigies of Premier Douglas, hanging from a noose (you can see them in the archival clip from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation below).

“We would like to defend the freedom of the individual and the doctors,” one woman who spoke at that rally urged. “The majority of the people of the province desire an immediate dispension of this act.”

Day by day though, the strike seemed to lose momentum. Turnout for that rally wasn’t nearly as high as the organizers had hoped. Patients wanted their doctors back. Meanwhile, the government refused to back down on the idea of government-run health insurance for all.

Saskatchewan flew in a British doctor to act as negotiator, helping the government and the doctors broker a deal. That deal became known as the Saskatoon Agreement. The doctors acquiesced to the single-payer system. The government, for its part, agreed that the doctors would remain independent contractors (rather than government employees, similar to how the National Health Service in Britain employs their doctors).

The doctors went back to work and single-payer began to spread to other provinces. British Columbia created a medical insurance program in 1965, largely modeled on Saskatchewan’s system. In 1966, the federal government passed a law where it would kick in money to finance these provincial health systems. The promise of federal funding quickly encouraged more provinces to create their own Medicare programs (including the most populous province, Ontario, in 1969).

Within 10 years of the Saskatchewan doctor strike, all of Canada was covered with government-sponsored health insurance.

“You have a single province who did it alone and then, a legislative framework that said these are the national standards in just three years,” Marchildon.

What Saskatchewan can teach the United States about health care: it’s hard, but it’s possible

Brooks is right: Canadians are really proud of their health care system. In 2004, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation ran a primetime special where they had millions of viewers vote on who was the greatest Canadian.

The winner wasn’t a hockey player — it was none other than Tommy Douglas, the father of Canada’s health care system. There are foundations and even a four-hour biopic film all devoted to Douglas, who is a pivotal figure in Canadian history.

Canadians are so proud of their health care system that it makes it hard to remember that there was a time when it was really controversial. The moment that it launched was a moment when it seemed like the whole thing might collapse.

If a future president tries to pass a Medicare-for-all system, it will undeniably be a brutal fight. There was a bruising political battle over the Affordable Care Act when it was passed, and that plan was significantly less disruptive than single-payer would be.

As more Democrats endorse the idea, health care industries are already creating new coalitions to fight back. Who knows, maybe the doctors here would go on strike too!

A Medicare-for-all fight would be hard because that type of system requires massive change. That was true in Saskatchewan in 1962, and it’s true in the United States. But hard and impossible are two quite different things, and there isn’t much that convinces me that we fall into a different category.

I asked Marchildon how he felt about this comparison: Is it fair to compare pre-single-payer America to the pre-single-payer Canada of the 1960s?

“I think it’s quite similar,” he said. “I don’t think the interests are, quantitatively, so much more powerful in the US than they were in Canada. What’s missing in the US is the federal government being willing to pull the levers in a way that allows states to innovate with their own solutions.”

Sarah Kliff is one of the country’s leading health policy journalists, who has spent seven years chronicling Washington’s battle over the Affordable Care Act. Recently, her reporting has taken her to the White House for a wide-ranging interview with President Obama on the health law — and to rural Kentucky, for a widely-read story about why Obamacare enrollees voted for Donald Trump.

Sarah is a senior policy correspondent at Vox.com, where she focuses on the Republicans’ effort to repeal Obamacare — and what that will mean for the millions of Americans who rely on the law for coverage. At Vox, she hosts The Impact, a podcast about how policy effects real people. She is also a co-host of The Weeds podcast with Ezra Klein and Matt Ygelsias.

Prior to joining Vox, Sarah covered health policy for the Washington Post, where she was a founding writer at Wonkblog, a blog dedicated to making complicated policy easily understandable. She has also covered health policy for Politico and Newsweek magazine.

She resides in Washington, DC with her husband and a very friendly beagle named Spencer.

Vox explains the news.

We live in a world of too much information and too little context. Too much noise and too little insight. And so Vox's journalists candidly shepherd audiences through politics and policy, business and pop culture, food, science, and everything else that matters. You can find our work wherever you live on the internet — Facebook, YouTube, email, iTunes, Instagram, and more.

Vox was launched at Vox Media in 2014 by founders Ezra Klein, Melissa Bell, and Matthew Yglesias.