On the Universalism of Notre Dame, from Muslim Arches to the Goddess of Reason

Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – The tragedy of the burning of the 800-year-old Notre Dame is a loss for global culture. Regular readers know that I grew up partially in France, and I love Paris with a passion. I remember visiting Notre Dame with my parents as a child. Perhaps there is a faded Kodak photograph somewhere. I had a fellowship at the Sorbonne in 2013 and lived near Notre Dame, which I used to visit occasionally, since it is one of my favorite buildings.

It is a great shame, however, that the loss is being commemorated in some quarters in a nativist way. This is, they say, about France, or Catholicism, or “Western civilization.” Of course it is about all those things, and what happened to this magnificent edifice is like a kick in the gut for us Francophiles. My heart goes out to all my French friends at this cultural catastrophe.

But the significance of Notre Dame is universal, not racial (!). For this reason, it is particularly regrettable to see an ugly hate speech meme circulate blaming the fire on French Jews or French Muslims. This vile anti-Semitism and abject Islamophobia is devoid of any hint of truth of course.

Notre Dame is a Gothic cathedral, and the French Gothic tradition of architecture was deeply influenced by Christian Neoplatonism. In particular, the thought of Plato, Plotinus and Iamblichus– pagan thinkers of antiquity and late antiquity– was worked into Christianity by figures such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 400s-early 500s AD).

And this thinker in turn was depended on by Abbot Suger (d. 1151), a major patron of the then new style of Gothic architecture. He wrote in his “On the Consecration of the Church of Saint-Denis,” that, as the Gale Group’s article says, “‘we made good progress—and, in the likeness of things divine, there was established to the joy of the whole earth, Mount Zion.’ In other words, the church was built as an image of heaven.”

Platonism holds that ideal forms are real, and this world is a pale reflection of them. The Gothic cathedral also was light and airy, with rose windows, reflecting Platonic light mysticism.

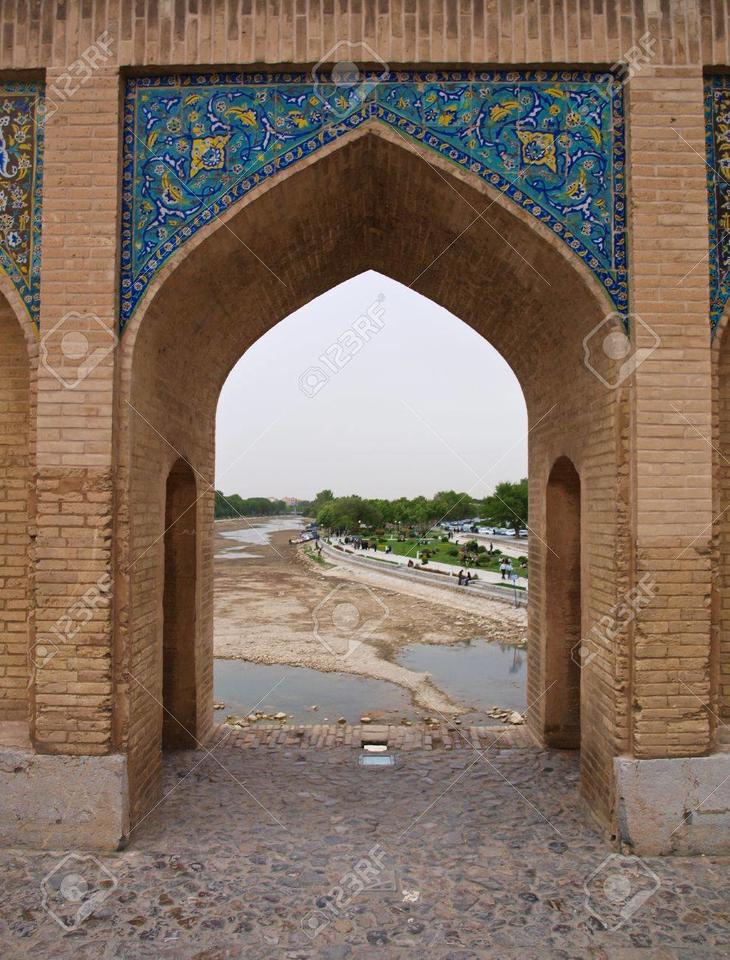

Not only did the Gothic cathedral receive substantial inspiration from Greek pagan thought, but some elements used in its architecture likely had Muslim, medieval origins via the influence of travelers or of Muslim Spain (Andalus). Some art historians have argued for the pointed arch as a Muslim development of a Sasanian Iranian form, which was then taken over into the Gothic cathedral.

Allah Verdi Khan bridge in Isfahan.

pointed arch in a cathedral.

(See Theodore Drab and Khosrow Bozorgi, “Reevaluating Middle Eastern Contributions to the Built Environment in Europe,” Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education; Vol. 21, (2003): 87-96 and Peter Draper, “Islam and the West: The Early Use of the Pointed Arch Revisited,” Architectural History Vol. 48 (2005), pp. 1-20; Draper concludes, “The history of Western medieval architecture, like that of Western culture in general, cannot be written without reference to the lessons learnt from Islamic culture, whereas the history of Islamic medieval architecture can be written largely without reference to the West.”)

Also arguing against seeing the cathedral in the light of traditional Catholicism or French nationalism alone is that little incident where Deist French revolutionaries of the local Commune and the Department of Paris on the 10th of Novemember 1793 (20 Brumaire II) gathered at 10 am at Notre Dame.

E. H. Gombrich explained (“The Dream of Reason: Symbolism of the French Revolution,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies [September 1979]):

that they installed a model of a mountain on top of which rested another model of a small Greek-style temple on which they had inscribed in huge script, “in honor of philosophy” (a la Philosophie).

Around it they set up four busts of philosophers, including Voltaire and Rousseau, and possibly Benjamin Franklin and Montesquieu.

They lighted a “flame of truth” at the altar.

Gombrich says,

- ‘After a suitable musical prelude, two groups of girls clad in white with tricolor belts and torches in their hands appeared from both sides, paid homage to the altar of Reason and ascended to the mountain. At that moment, a beautiful woman, [faithful image of beauty] image fidèle de la beauté, came out of the temple. She, too, was clad in white with a blue cloak floating from her shoulders; she wore the red bonnet and held a long pike in her right hand. The congregation, if we can call it so, sang a hymn to liberty by Marie Joseph Chenier: [Descend, Liberty, daughter of nature] “Descends, 0 Liberté, Fille de la Nature”, which ended: [“You, holy Liberty, come dwell in this temple, Be the goddess of the French] “Toi, sainte Liberté, viens habiter ce temple, Sois la déesse des Francais!” ‘

When the ceremony concluded, the celebrants carried the goddess of Reason to the parliament or National Convention, since the deputies had not participated in it.

Needless to say, Ben Franklin was the furthest thing from a Catholic, but his legacy was intertwined with that of the Notre Dame in 1793, as a symbol of universal reason.

In the years before the Revolution, the position of free persons of color became an issue even in France, but especially in the French Caribbean. Michaela Ahlstrom observes, “Factions in France had started to openly take up the abolitionist movement. The Société des Amis des Noirs [Society of Friends of Blacks] was formed by Condorcet who pushed a platform that was even addressed at the momentous “calling of the Estates General” in Paris in 1789.”

The Rights of Man, issued by the French revolutionaries, makes no mention of race, and the same revolutionary parliament that celebrated the goddess of Reason voted to abolish slavery (the decree was not widely observed and counter-revolutionaries found a way to blunt its force and then reverse it for decades). It also voted to give equal rights to free persons of color in French colonies in the Caribbean, and provided a platform on which French of African heritage in Haiti went on to stage an egalitarian revolution. The goddess of Reason and Liberty, worshiped at Notre Dame, was universal in her impact.

The Notre Dame is not narrow, not a symbol only of Paris, or France, or the Roman Catholic Church. It is a world-historical edifice, reflecting the light mysticism of Plato and the pointed arches of Zoroastrian Iran and Abbasid Baghdad, and at one stage of its long existence it symbolized universal Reason and political Liberty, a Reason and Liberty that knew no nation or race and which aimed at emancipating persons of color along with everyone else.

As I write, it appears that the twin towers of the cathedral remain sound, and that it can and will be rebuilt. Let us all contribute to that effort, because this edifice is intertwined with the humanity of all of us. And let us celebrate its universalism, so different from the narrow and racialized significances with which the Far Right is investing it.

Here are some suggestions for donating to rebuild.