Who Controls Our Time?

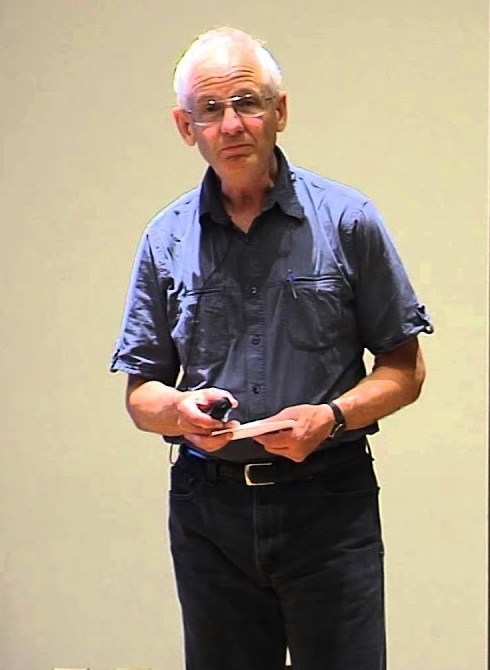

Moderators Note. This week many of us were stunned with the sudden passing of our friend and comrade Dan Clawson, just a week before we were to gather and celebrate his retirement from work, but not the struggle to make the world a better place. Here are some remarks from Labor Notes and Phenom about Dan.

Labor Notes

"Dan Clawson was a longtime labor activist, organizer, and scholar, and the author of The Next Upsurge: Labor and the New Social Movements among other books. Rarely out in front, but always leading from behind, Dan was a mentor and advisor to union members and activists across the country. Closer to home, he was a founding member of the Educators for a Democratic Union caucus, which won the leadership of the Massachusetts Teachers Association in 2014. EDU pushed to open up the bargaining process to members and community and to transform the union into a more democratic and militant organization; in 2016 the MTA drew national acclaim when teachers beat back a heavily funded push for corporate charter school expansion. Dan wrote for Labor Notes several times, most recently co-authoring an article that appeared in our April issue: "Who Controls Our Time?"

Phenom

Many in PHENOM may never have heard the name Dan Clawson. But without Dan there would be no PHENOM. It was Dan Clawson, a sociology professor at UMass Amherst, president of the faculty and librarian union at UMass Amherst, who first pushed the idea of an independent organization that would advocate for public higher education. When the opportunity arose – a December 2006 visit of Governor Deval Patrick to UMass just before the very start of his administration – Dan orchestrated the writing of a visionary statement of the goals for public higher education. Two months later, PHENOM was born.

When few were willing to talk openly, much less build an organization around the idea of free higher education, Dan was happy to do so. PHENOM held, and still holds, this idea as a core principle. It has become a mainstream political idea, widely discussed in presidential campaigns, and here in Massachusetts.

Dan was also a nationally known and revered professor of sociology. He wrote nine books and dozens of articles, many about building more just workplaces, and how to revitalize the American labor movement. He also wrote a book on the future of public higher education and was a constant critic of the privatization of our public universities. Indeed, this summer he was organizing a plenary panel on the neoliberal university for the American Sociology Association meeting.

Most fundamentally, Dan was an organizer. He never sought the limelight, but rather built and promoted organizations, caucuses, movements and candidates he thought could help support an “upsurge” in militant social justice movements, especially those rooted in labor unions. Just days before he died, he was busy helping elect progressive candidates at MTA’s Annual Meeting, and helping to pass a call for a national strike for the Green New Deal.

Whether we knew him personally or not, we will all miss him in the continuing struggle for the Commonwealth we all want to live in.

Dan Clauson

Who Controls Our Time?

As the bumper sticker has it, unions are “the folks who brought you the weekend.” Unions fought for the 10-hour day, and then the eight-hour day… and then our fight stopped. We never got to a six-hour-day fight.

Instead we started to backslide. We not only lost the weekend; we lost control over our time. This slippage mirrors the decline in real wages over the last generation—both signs that organized labor has gotten weaker.

In 1960 the paid work hours for U.S. workers were roughly comparable to those in Europe. These days, U.S. workers put in at least 300 more paid work hours per year than workers in Scandinavian countries, Germany, or the Netherlands, and at least 250 hours a year more than workers in France, the U.K., or Austria.

Today, struggles over work time are more defensive than offensive. Some workers want more hours, while others want fewer. Still others are campaigning for paid family leave.

People don’t always understand these struggles as connected. But we see a principle that underlies them all: everyone wants more say over when and how much they work.

TIME TO GET WELL

Denying sick leave is often the clearest and most outrageous way that an employer states his view of the world: that the job comes before everything; that his profits are what counts.

Consider the situation five years ago at a typical (nonunion) nursing home in Massachusetts. On paper, the workers got paid sick leave—six days a year. But if they actually used a day of sick leave they got a verbal warning; a second day led to a written warning; a third day, a stronger warning; the fourth day, the worker was fired.

It didn’t matter why the worker was out, even if her child or mother, or she herself, was hospitalized. The clock reset every 90 days, but suppose you’re a single parent with two kids. One gets sick, then the other gets sick, and soon you’re in a bind. Do you leave the sick child at home alone (and get blamed for being a negligent parent) or miss work and get fired?

In Massachusetts and a dozen other states, plus numerous cities, unions and community groups have mounted campaigns and voters have passed laws guaranteeing all workers paid sick days and the right to use them without penalty.

The story is similar for family leave. Federal law says firms must guarantee 12 weeks of leave to workers with a new baby or an immediate family member who’s seriously ill. But the leave is unpaid, and applies to only 40 percent of workers—those who have enough hours at a large-enough employer. It also doesn’t apply if you’re caring for a relative who isn’t considered immediate family.

Polls show large majorities of voters support guaranteeing paid sick leave (85 percent) and paid family leave (82 percent for mothers following the birth or adoption of a child). When these measures get on the ballot, they win: 10 states and Washington, D.C., require paid sick leave, and five states and D.C. will require paid family leave by 2020. In many more states such legislation is pending.

But even when the laws pass, enforcement is a problem. Between a quarter and a half of covered private employers do not provide the benefits required by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act. Unions help; a U.S. woman is 17 percent more likely to take maternity leave if she is represented by a union.

SCHEDULE FIGHTS

For many low-wage workers, the key problem is getting enough hours to support themselves and their families. Employers have gotten creative, creating unpredictable work schedules that minimize paid hours by keeping workers in limbo.

Retail sales workers face “just-in-time scheduling,” or as one put it: “I have a ‘maybe’ schedule.” Odd hours are posted and changed at the last minute; workers are expected to drop everything to come to work. If the weather changes or customer demand drops, workers are sent home without pay.

Young workers especially are coming to assume they can’t expect the kind of “regular hours” that would let them make plans and keep them.

Employers use a variety of high-tech scheduling programs to avoid “overstaffing” and paying for full-time work. After all, what we call downtime or adequate staffing, they call waste. Companies can boost profits if managers can shave even 15 minutes off the schedule, and do that a few dozen times a year to thousands of workers.

Here too, workers are fighting back, and some are winning laws to control these abusive scheduling practices. (See box.)

TOO MUCH OR TOO LITTLE?

UPS is a poster child for two opposite scheduling problems. The workers who load and unload packages are overwhelmingly part-time. They want full-time jobs with better pay and benefits.

Meanwhile package car drivers only have the right to request to go home after 9.5 hours—and they have a really hard time enforcing even that. To top it off, the company can now assign weekend work without paying a premium.

Too many hours and too few hours can work to reinforce each other. Some workers are kept under the part-time threshold, to avoid paying health benefits, by piling more work on existing full-timers.

In many industries, workers differ—some want overtime, others don’t. The key is that workers through their unions should get to negotiate a fair system.

Some unions—for example, firefighters—develop elaborate contract provisions to be sure that every worker has an equal chance to work overtime, seen as a valuable perk. In other unions—for example, nurses—the union contract more often focuses on ways to avoid mandatory overtime, as unpredictable hours create family problems.

Another variation: often workers want to concentrate their hours into fewer days, working four 10-hour days instead of five eights. Nurses often choose to work three 12-hour days; in some places their unions have won 40 hours’ pay for that schedule.

A NEW WORLD

In Britain, the Trade Union Congress (roughly the equivalent of the AFL-CIO) recently proposed fighting, over the long term, to move to four eight-hour days—with weekly pay staying the same.

Even when our demands sound opposite, most workers want similar things: a predictable schedule with reasonable hours that ensures acceptable wages, health benefits, and time off to care for oneself and one’s family. We should reunite around those shared demands.

And whether we’re fighting for a contract or a law, we should frame every time-related fight as part of the same vision—that workers own our time.

Laws to Curb Scheduling Abuses

Emeryville, California, recently enacted the Fair Workweek ordinance, which requires employers in the retail and fast food industries to offer adequate notice of work schedules and additional work hours—up to 35 hours of work in a week—to existing workers before hiring additional workers or subcontractors.

San Francisco passed a Retail Workers Bill of Rights in 2014 that requires employers to announce schedules two weeks in advance, provide extra pay for changing a schedule, and award at least two hours’ pay if workers are sent home before their scheduled shift ends. Advocates from Jobs for Justice worked with the Food and Commercial Workers to win these improvements.

Under Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance, which UFCW Local 21 and Working Washington pushed, employers must pay no less than one-half their regular rate of pay for any hours scheduled and then rescinded.

New York City passed two Fair Workweek ordinances in 2017 with the efforts of RWDSU (retail) and SEIU 32BJ (fast food). One requires many fast food employers to provide at least 15 days’ notice of work schedules. The second requires retail employers to provide at least 72 hours’ notice of work schedules, and not to schedule employees for on-call shifts to cancel shifts with less than three days’ notice.

Dan Clawson and Naomi Gerstel teach sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and are the authors of Unequal Time: Gender, Class, and Family in Employment Schedules.

A version of this article appeared in Labor Notes # 481. Don't miss an issue, subscribe today.