The Democratic Revolution in Sudan: Testing Days Ahead

The Democratic Revolution in Sudan: Testing Days Ahead - Rashid El Sheik (Morning Star)

Sudan’s Uprising, Bashir’s Fall, and My Father’s Passing - Isma’il Kushkush (The New Yorker)

The Democratic Revolution in Sudan: Testing Days Ahead

by Rashid El Sheik

May 27, 2019

Morning Star

Last Tuesday the Supreme Military Council broke off negotiations with the civilian Freedom and Change Alliance.

On Thursday it started to roll back some of the key gains of the past six months — announcing the reimposition of state control over trade unions and making independent trade unions once more illegal.

The Military Council did so for good reason — because it knows the potential power of the organised working class to carry through the democratic revolution.

Sudan’s revolution started in one of the most impoverished regions of Sudan, in the Blue Nile province on December 13 and quickly spread to the major cities, culminating in mass demonstrations in Khartoum on December 19. By then those mobilised in the city centres were numbered in millions.

The demonstrators were young. A big proportion were women and they were largely secular. It was a mass response to years of repression and marked a transformation of attitude in a country that had been run by a Muslim Brotherhood terroristic dictatorship for over 30 years.

By April 11, after four months of democratic mobilisation and after splits developed in the armed forces, the regime’s leader, General Omar al-Bashir, was at last forced to resign. However, those he represented are still at large and have regrouped.

Counter-revolution is now on the march — although, probably critically, its forces, as represented on the Supreme Military Council, are divided.

On the one side are those funded by Qatar, Turkey and countries associated with the Muslim Brotherhood.

On the other are those associated with the UAE, Egypt and above all Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia has over recent years paid for a significant part of the Sudanese army to fight in Yemen.

A couple of weeks ago it transferred $500 million to Sudan’s Central Bank. It is ultimately backed by the United States.

A key figure in the current counter-revolutionary offensive is Mohamed Hamdan Hemeti. Previously leader of the Janjaweed militia, and orchestrator of the genocidal killings in Darfur, his forces were integrated into the Sudanese army as the “Rapid Reaction Force” and operated as the old regime’s paramilitary militia.

They are still operating in their thousands in Sudan’s cities and were responsible two weeks ago for the killings of demonstrators encamped outside the military headquarters.

“General” Hemeti is second in command of the Supreme Military Council. A mercenary and opportunist, his Rapid Reaction Force is currently funded by the UAE and Saudi Arabia and also receives millions of euros from the European Union to police Sudan’s western, southern and eastern borders.

In addition to these splits in the military leadership, the army’s junior ranks and rank and file have shown themselves on occasion willing to be supportive of the democratic forces and are resentful of the “Arabisation” of the army and the dominance of the paramilitary Rapid Reaction Force.

In the face of the counter-revolutionary offensive the democratic forces have demonstrated remarkable courage and fortitude.

They regrouped immediately after the military assault and still occupy central Khartoum. Their numbers have never fallen below 100,000 in a tented city and are supplied with food and sustenance by many more.

They are overwhelmingly young. They are active and organised — with music, theatre and discussion groups.

The demand of the Freedom and Change Alliance is for the immediate transfer of power to a civilian-led government and elections for a parliamentary legislature.

The proposal refused by the Supreme Military Council last week was for the military to have a third of the seats on the new interim government council with two-thirds from the Alliance. The military is demanding two-thirds.

The response of the Alliance has been to seek pledges of support for a general strike from organised workers.

These have now been forthcoming from trade unionists in transport, the docks, airports, airlines, the banks, health professionals, the universities and schools and sections of private industry.

This two-day general strike has been called to begin tomorrow. Adding strength to the Alliance has been the arrival in Sudan on Sunday, despite a death sentence placed on his head, of Yasser Arman, second in command of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (North).

He was accompanied by General Hamrese Galab of the SPLA(N). The SPLA is pledged to support the Democracy and Freedom Alliance.

The Sudanese Communist Party remains a key organisation in maintaining the unity of the democratic alliance.

Its paper is now published three times a week and its social media reach even more. Solidarity and understanding from all progressive organisations in Britain will be critical in the testing days ahead.

Sudan’s Uprising, Bashir’s Fall, and My Father’s Passing

By Isma’il Kushkush

May 16, 2019

The New Yorker

Photograph from dpa / Alamy // The New Yorker

On the evening of April 11, 2019, I set my alarm for 5 a.m. I was scheduled to do a series of TV interviews the next morning, to discuss the fall of the Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir. I had spent eight years reporting in Sudan as a freelance journalist, mostly writing for the Times. At 3 a.m., my brother called and asked me to meet him immediately. Our father, who had been hospitalized for four months, had passed away. I cancelled all commitments.

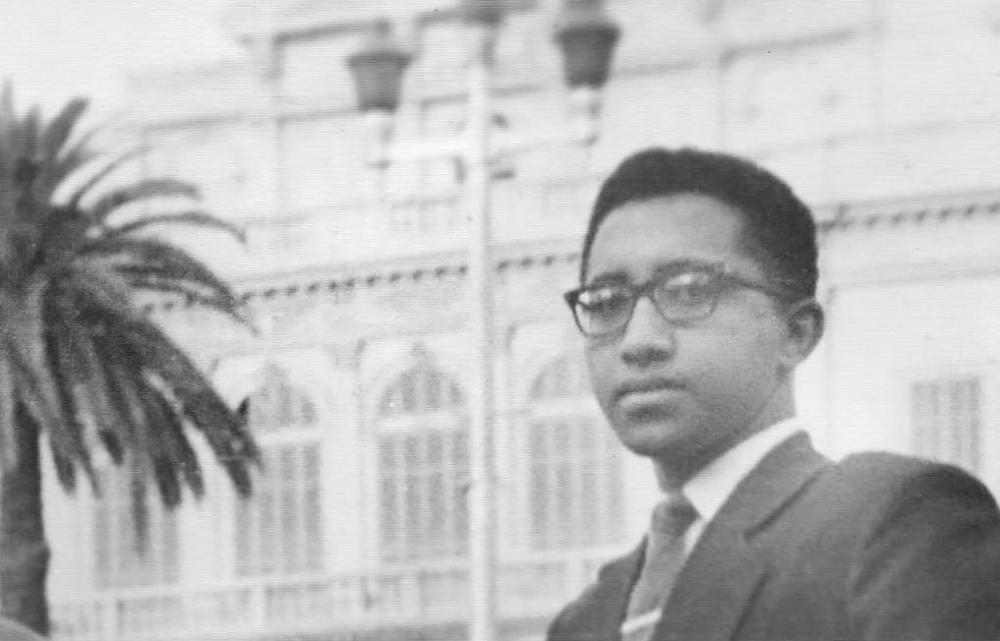

An immigrant from Sudan, my father grew up in the nineteen-sixties, an era when many bright young Sudanese students won scholarships to pursue higher education in the U.S. A graduate of the University of Khartoum, in Sudan, he had studied to become a wildlife expert. But decades of mismanagement, war, and man-made drought devastated the country’s national parks. A five-star hotel replaced Khartoum’s only zoo.

In 1964, my father participated in the October Revolution protests, which unseated Sudan’s first military dictator, Ibrahim Abbud. My father belonged to a generation that had big dreams of progress—the “generation of giving,” as one Sudanese poet called it. In 1980, having completed a Ph.D. in ecology at the University of California, Davis, he returned to Sudan with high hopes for the country. Within a year, the political and economic realities of the time—dictatorship, inflation, and unemployment—forced my father and many of his peers to reluctantly leave again and live abroad, as émigrés.

Photograph Courtesy Isma’il Kushkush

Last December, my father suffered a stroke, ten days after a wave of street protests had broken out in Sudan. He had followed them closely, on Arabic satellite TV channels. The protests first started in Atbara, a town in northeastern Sudan where he had lived as a child, and where my grandfather had worked as a railroad-station manager. High-school students took to the streets after the price of bread tripled overnight. Protests quickly spread across the country, peaking on April 6, 2019, in Khartoum, on the anniversary of the April 6, 1985, uprising that unseated another dictator, General Jaafar Nimeiri. I remember my father listening day and night to radio news broadcasts of the 1985 uprising from Kuwait, where we lived at the time.

In the sixty-three years since Sudan achieved independence from Britain and Egypt, the country has fluctuated between civilian rule and military dictatorship; it has endured civil war, drought, and economic decline. Many Sudanese people, particularly in the middle class, believe that the country was in a better place during the early years of independence. They reminisce about the superior quality of the colonial-era educational system, trains that ran on time, and a national soccer team that dominated Africa. Bashir’s reign for the past thirty years has been particularly harsh, with the decline of the civil service, allegations of genocide in Darfur, and the secession of South Sudan, after twenty-two years of civil war. At the core of Sudan’s instability has been its lack of a permanent constitution and disputes about whether the country should be a liberal democracy or a socialist or Islamist state, and whether Sudan is Arab, African, or both. Like many Sudanese people of my generation, while I was growing up, I was inundated with stories from my parents about what Sudan was and complaints about what it has become.

When the Sudanese took to the streets in December, it was a moment for many of us to restore our trampled-upon sense of dignity, our pride in what Sudan once was and what it could become. I had argued with my father that Sudan had always, in fact, faced challenges, including deep prejudice and, as a result, staggering economic inequality between its major cities and its peripheral regions. Though I told my father that his perception of the country’s past was rosy, for him, and many others, that image of Sudan was a source of fulfillment and hope.

After my father’s stroke, I spent my time caring for him in a hospital in the Washington, D.C., area and reporting on Sudan from afar. After his death, I tried to balance my duty to perform religious and cultural mourning rituals with following an important moment in Sudanese history. Requests for interviews, contacts, and advice mixed with messages of condolences from family and friends in the U.S. and overseas. I answered calls from odd-looking numbers that I would have normally ignored, concerned that I could inadvertently offend overseas relatives by failing to answer. Working as a journalist in conflict zones in Sudan and elsewhere helped me manage my emotions at trying times, including when I helped prepare my father’s body for ritual washing, prayers, and burial.

It is still early to determine where Sudan is headed. Many Sudanese fear a “deep state” of military and intelligence officials that will refuse to relinquish power or the interference of powerful countries in the region. Protesters are demanding an immediate transition to civilian rule, to avoid the mistakes of Sudan’s past and those of the Arab Spring. I’ve been reluctant to use the word “revolution,” but the qualitative differences and revolutionary nature of the current uprising should not be ignored. Youth, women, and minorities all played a leading role in the protests. The Sudanese people have displayed a rejuvenated sense of civic duty. Frank discussions about the country’s problems have revealed a sweeping commitment to change. Perhaps this generation will finally bring about, and add to, the dreams of that “giving generation,” creating a Sudan that will bring its people and my father peace.

[Isma’il Kushkush is a freelance journalist living in Washington, D.C. He was previously based in Khartoum, Sudan, for eight years.]