This Hidden Mural on South Ashland Avenue Tells the Story of One of the Most Radical Labor Unions

Anyone driving on Ashland Avenue near Monroe Street has likely seen the colorful mural on the side of the United Electrical Workers union hall.

Completed in 1999 by Mexican artist Daniel Manrique, it shows people joining hands in solidarity and celebrates international unity among workers.

Less well-known because it’s out of public view is the two-story mural inside, completed in 1974, that climbs the hall’s main staircase, immersing anyone who walks through it in the history of the union.

Hands clasp in this portion of the “Solidarity” mural inside the United Electrical Workers union hall at 37 S. Ashland Ave. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

The walls of the “Solidarity” mural — which will be part of the Chicago Architecture Center’s annual Open House Chicago tour, open to the public Oct. 19-20 — are plastered with brightly colored scenes of workers’ struggles and triumphs. Hands of different races clasp together, a cartoonish boss is forced to sign a contract with workers, and union leaders hand leaflets to factory workers.

The second-floor landing portrays a southern sheriff, a Ku Klux Klan member, an industrialist, a general and National Guard members suppressing the workers below them.

Chicago Public Art Group

Murals have long told stories of the labor movement. Larry Spivack, president of the Illinois Labor History Society, says this one “captures the essence” of labor activists in ways history books can’t always do, helping those who view it connect with the stories.

“The mural is an exciting, beautiful way of telling the history,” Spivack says, “a lesson for all of us who are interested in a better quality of life, a better society, one that has less wage inequality and less racial division.”

The United Electrical Workers union hall stands out for the mural work on the outside of the building at 37 S. Ashland Ave., but there also is striking work inside. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

When artists John Pitman Weber and Jose Guerrero, who were determined to make the inside of the UE Hall their canvas, first approached the UE in 1973, the building and the union both had seen better days.

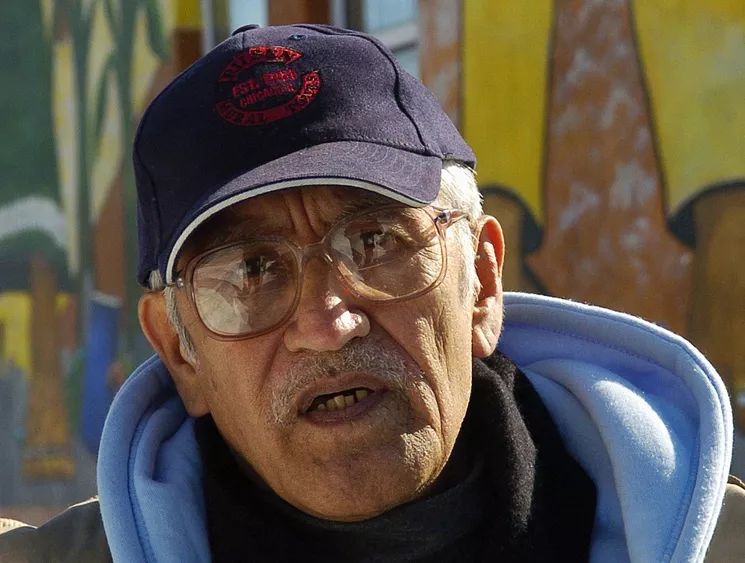

Jose Guerrero in 2008. Sun-Times files

Weber, a muralist, and Guerrero, a self-taught cartoonist, had been introduced by friends and decided to collaborate on a mural about labor and workers. Guerrero, who died in 2015, was a factory worker at the old Sunbeam Appliance Co. plant on the West Side, and Weber was born into a family of radical activists.

Weber, who in 1970 co-founded the group now known as the Chicago Public Art Group with William Walker, says the UE seemed a perfect fit because its ideals of a progressive and militant tradition aligned with his and Guerrero’s vision.

Chicago’s murals & mosaics

“The building was old and had these difficulties, and that didn’t frighten us at all,” Weber says. “We were viewing this as an opportunity to identify with one of the few unions that was still carrying a radical tradition.”

Weber, 77, says that tradition might have been one reason the union was so open to the artist. Another: They were willing to work for nothing.

A portion of “Solidarity” inside the United Electrical Workers union hall at 37 S. Ashland Ave. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

“They had lost membership, but they liked us, and we liked them,” Weber says. “Both Jose and I really believed in the dignity of labor and the importance of fighting.”

The union couldn’t afford to pay Weber and Guerrero, but it supplied paint. Both artists had full-time jobs, Guerrero at Sunbeam, and Weber teaching at Elmhurst College. So they painted on weekends and evenings.

Weber says the union’s members made them feel at home, even giving the artists the keys to the building.

A portion of the “Solidarity” mural inside the United Electrical Workers union hall at 37 S. Ashland Ave. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

It’s now 45 years since the mural was completed. Carl Rosen, the union’s western region president, says he has “a lot of attachment to it.” Rosen grew up in a union home — his parents were union activists, and his father was a UE member.

The UE is an independent union representing 35,000 workers nationwide ranging from sheet metal workers to scientists and librarians.

The mural was restored in the mid-2000s, when a UE convention came to Chicago. It remains in good condition except for cracks in the plaster, and Rosen says the gentrifying surrounding neighborhood poses more of a threat to the mural than age does.

Across the street, there used to be a Salvation Army halfway house. Behind it were drug- and alcohol-treatment centers. Now, upscale housing seems to be all around. A luxury apartment building opened next door last year on a lot that had been vacant for years.

Rosen says he has gotten offers to buy the union hall but turned them all down. Still, the hall is getting too big for the regional office, so space is being rented out to other unions and nonprofits.

“We are cognizant of the fact that this neighborhood is changing,” Rosen says. “So whether, at some point, it kind of pushes this out, you know, is possible. But we’re not out there soliciting offers.”

Among the images on the interior walls of the United Electrical Workers union hall at 37 S. Ashland Ave. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

Weber is pleased his and Guerrero’s mural will be part of Open House Chicago. He says it shows that works of public art are viewed as valuable parts of the city’s heritage.

“I’m delighted that it’s still there and that people are going to see it,” he says.

The UE hall is better known for the mural on the outside of the building at 37 S. Ashland Ave. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

Syd Stone is a Metro News Intern at Chicago Sun-Times