In Coal Country, the Mines Shut Down, the Women Went to Work and the World Quietly Changed

FLEMING-NEON, Ky. — In the pre-dawn hours when all is dark and quiet, Amanda Lucas leaves her house and begins the long drive to her job at a hospital an hour away.

In years past, it was the men who would empty out of the hollows of Letcher County before sunrise. All day long they would be underground, digging out coal as their fathers and often their grandfathers had done. Ms. Lucas’s husband, Denley, had a job with one of the big mining companies, with good benefits and an income approaching six figures when all the overtime was added. She stayed at home to raise their four children.

“We had a good life,” she said.

Then everything changed.

It has been a hot and mean summer in Letcher County, with a rash of coal mine bankruptcies and layoffs even crueler than the ones that came before. From the barstools at the American Legion post to the parking lot of the unemployment office, there was little debate: The coal business around here is going under. The only question was what would keep everyone afloat.

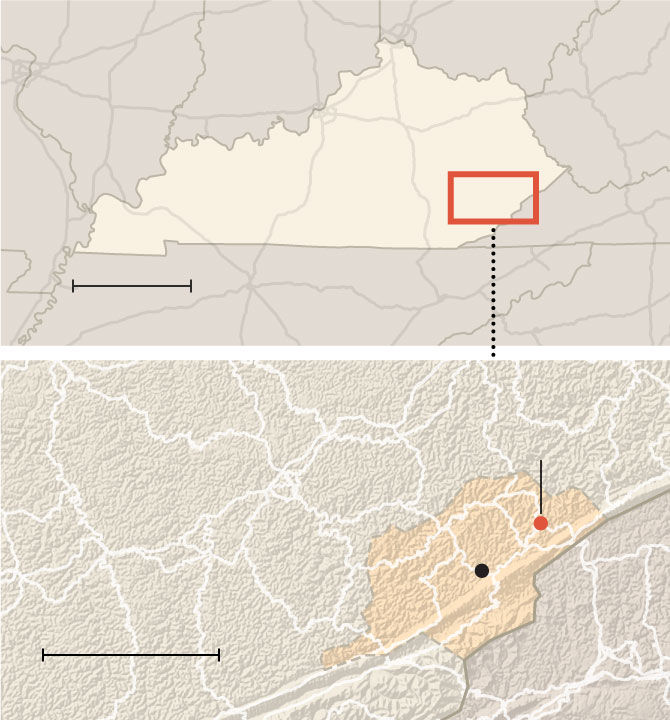

These days, the answer has been: women. From 2010 to 2017, Letcher County saw a greater shift in the gender balance of its labor force than almost any other county in the United States.

The share of women in the work force rose substantially in places throughout Central Appalachia, as well as in parts of the industrial Midwest and the rural South. But few places have seen a more dramatic change than Letcher County, in hilly Eastern Kentucky, where for generations the archetypal worker was a brawny, coal-dusted man in reflective overalls. Just 10 years ago, nearly three-fifths of the work force was male. Now the majority is female.

“The mines have shut down and the women have gone to work,” said Billy Thompson, a district director of the United Steelworkers union, which represents thousands of medical support workers in the region. “It’s not complicated at all.”

The Quest Energy mine in Deane, Ky., is currently inactive.Credit: Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

There are over a thousand fewer coal mine jobs in Letcher County than there were a decade ago, and virtually all of those lost jobs were held by men. The number of mining jobs, according to state figures, fell to under 50 in 2017, from over 1,300 at the beginning of 2009. The number has inched back up; this summer it was 100.

Coal mining has always been boom-and-bust, but it is hard to shake the feeling that this might be the last bust. Some men picked up and left at word of mining jobs elsewhere, some went to work as linemen or truck drivers, and others, figuring they were too old or physically broken to start over, just dropped out of the labor force. It was as if the very identity of a Letcher County man had been declared insolvent.

“I could always tell the man who worked in the mines,” said Debbie Baker, a cleaner in Whitesburg, the Letcher County seat. For one thing, “they had money.”

She recalled a family who lived comfortably where she grew up; the father worked underground and his sons followed, one by one. “The next would get old enough and get a wife and go working in the coal mines,” she said. “I don’t think any of the men did anything else.”

“When the mines left, they all ended up on drugs,” Ms. Baker added. “And their women went to work.”

Women in coal country always found paying work in greater numbers during the lean times, cleaning houses or making burgers, earning enough to get the family by until the mines picked up again. When that happened — and it always did — wives often returned home or cut back on hours because they could and because someone had to, child care being an elusive commodity. But just tiding the family over is not enough anymore.

There is little hope of finding work that could replace a miner’s income; women in Letcher County still on average make substantially lower salaries than men. But in a place stricken by chronic disease and opioid overdoses there is one area where workers are in constant demand: health care. Signing bonuses for nurses can reach into the five digits.

It is impossible to miss driving into Whitesburg. Heading in from the east, there is an outpatient mental health clinic taking up a roadside mall and then, on a perch overlooking downtown, the county’s major hospital, founded by the miners’ union in the 1950s and recently expanded. Coming in from the west, there is a brand-new heart, vascular and neurology clinic that opened in the old Super 8 hotel building, and just beyond it, across from the grocery store, is the 75,000-square-foot Mountain Comprehensive Health Corporation clinic.

This is the region’s economy now, and its work force. At the regional network of M.C.H.C. clinics alone, there more than 110 nurses, according to Mike Caudill, the chief executive. Four of them are men.

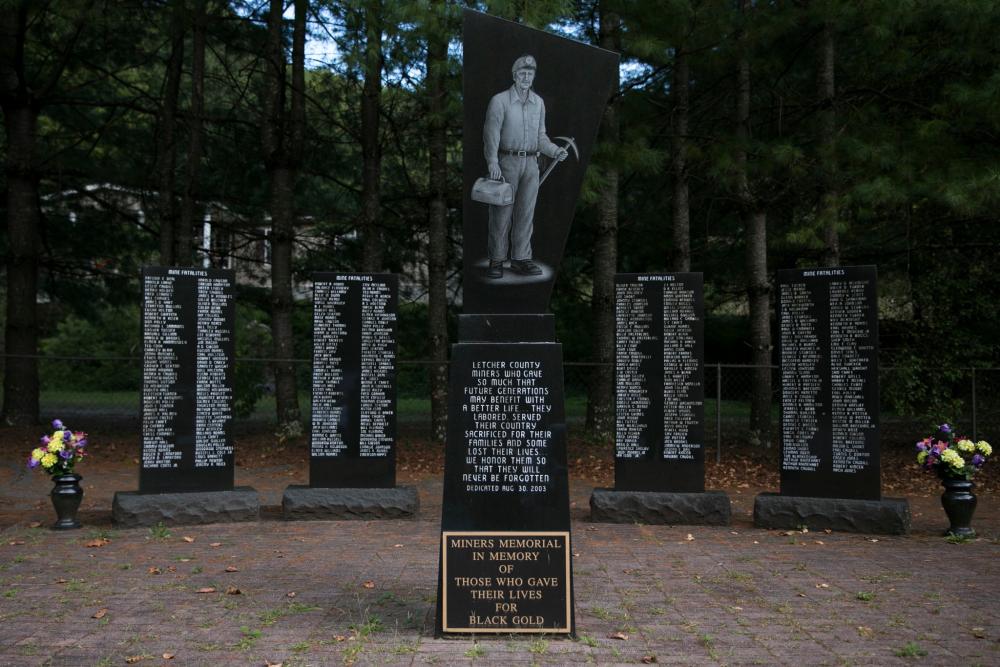

A shrine to those who died in the Letcher County mines at the Hemphill Community Center in Jackhorn, Ky.Credit: Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

A light illuminates the evening in a hollow near Neon, Ky., in Letcher County. From 2010 to 2017, the county saw a greater shift in the gender balance of its labor force than almost any other county in the United States.

Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

A car rolls through Neon, Ky., an unincorporated town in Letcher County, near the border with Virginia.Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

From Miners to Nurses

“We wouldn’t have half the nurses that we do if we still had coal mines,” said Ciara Bowling. She certainly wouldn’t have decided to go to work herself. As far back as she can remember, she wanted only to be a coal miner’s wife.

But Ms. Bowling, 25, came out of high school into the coal bust. Her boyfriend, already laid off, drove the county roads asking about openings at the mines, while she earned their living at the dollar store, then the Pizza Hut, then the McDonald’s. Most of the women she worked with, she said, were wives of out-of-work miners.

The idea was always to quit when the men found jobs. This was the arrangement articulated by a friend of Ms. Bowling’s, a former miner named Jody Ray Rose: “A man works and does what he’s supposed to do, or has to do,” Mr. Rose said, “to take care of his family.”

But without the mines this was nearly impossible. Ms. Bowling and her boyfriend sold their TV and refrigerator; at one point they had their water cut off. He never found a mining job. After they split up and Ms. Bowling started seeing a new man — also looking for work underground — she enrolled at the local community college to become a medical assistant.

“Take care of your husband, that’s all you want to do,” she said. “But when that doesn’t work out, you’ve got to go to work.”

This is the conversation Ms. Lucas, the hospital worker, and her husband began having when the coal business started falling apart. Even before he was laid off, the Lucases, with four young children and a mortgage, had been watching mines shut down one after another. More than a decade after dropping out of college, Ms. Lucas, 38, raised the idea of going back to school.

Multiple healthcare facilities line the routes into Whitesburg, Ky., including the 75,000-square-foot Mountain Comprehensive Health Corporation clinic.Credit: Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

“To be honest, I wasn’t real crazy about it to start,” her husband said, sitting with Ms. Lucas in a living room noisy with children on a Fourth of July afternoon. He saw it as his obligation to ensure that she didn’t have to work, an obligation he’d kept for 18 years. But she wanted this, he said, so he didn’t get in the way.

As it was, they needed it. A state program for miners’ families not only paid tuition but, critically, also provided money for living expenses. Ms. Lucas spent long days studying while her mother and sister-in-law helped Mr. Lucas with the children.

After graduation, Ms. Lucas went straight to work as a respiratory therapist. The job comes with health insurance, but it doesn’t draw the salary Mr. Lucas used to earn in the mines. That is a reality common to care workers, looking after people who made more money than they likely ever will. She sees former miners suffering from black lung and other ailments she has known firsthand in her own extended family. She thinks of the work as an act of reciprocity.

“They helped us to establish everything around here, and now I can help them,” said Ms. Lucas, who is now training other wives of out-of-work miners at the college. “I’ve always heard if you love what you do it don’t seem like a job, and that’s how I feel right now.”

The family has learned to live on less. Mr. Lucas works construction jobs when the opportunity arises, but he hasn’t ruled out going back underground.

“I liked it pretty good the way it was and I’m sure she did too,” he said, nodding toward his wife. It was true that working in the mines was rough, and he appreciates his wife’s success. “I’m sure she’s glad she’s done what she did, and I understand that,” he said.

“But,” he repeated, “I did like it pretty good the way it was.”

“Things Have Just Changed”

Ms. Bowling had ultimately found a life like the way it was, or the way she’d long wanted it to be. Her fiancé, Blake Johnson, had found a job in the mines. Every day he went in before sunup and came home 12 hours later, exhausted and coated in coal dust.

“We as a community are so proud of our miners,” Ms. Bowling said. She was sitting on a hot afternoon at the Hemphill Community Center, in a building that once housed a long-shuttered grade school. In the parking lot stands a shrine to those who died in the nearby mines, the names listed on black marble of miners “who gave so much that future generations may benefit with a better life.”

Mr. Johnson’s father was killed in the mines. His brother was laid off this summer, after decades with one company. He had few illusions about coal work. He wanted to go back to school himself and when he got a good job, he said, Ms. Bowling would no longer have to work.

She has different ideas. “Things have just changed,” she said.

Ciara Bowling and her fiancé, Blake Johnson, outside their home in Fleming-Neon, Ky. Mr. Johnson has few illusions about coal jobs. He wants to go back to school and get a good job, he said, so Ms. Bowling would no longer have to work.Credit: Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

She didn’t drop out of school when Mr. Johnson got his mining job, as she would have done in years past. There was now the prospect of real independence, of not always having to defer to a husband because he paid the bills.

“Women now, they got a little taste of freedom,” Ms. Bowling said. “Men has been able to do whatever the hell they want for so long while women has had to sit in a chair and keep their legs closed and be nice and polite. Now they don’t have to.”

It felt strange to be saying these things out loud, she said. There were plenty of men less open to change than Mr. Johnson, who had supported her going to school. Her friend Mr. Rose, for example: He didn’t want his wife working at all. But none of them, she said, understood how big a shift was underway.

“All these men, they just don’t know what’s about to happen,” she said.

“They’re not going to be able to sit at the house and do nothing. They are going to have to help. Because she is going to have just as much invested in their life as he does.”

In August, Ms. Bowling started her long days of clinical rotations. Mr. Johnson was laid off.

A short drive from the community center up Coal Miner’s Highway, in a house his grandfather built, Mr. Rose considered the way Ms. Bowling went about things, and the way preferred by men like himself.

“We’re definitely a dying breed,” he said. He had been released from prison a few weeks earlier — drugs — and was now delivering merchandise for a hardware store. Getting back underground was the aim, but he wanted his sons to see how it was supposed to be: him hard at work and their mother at home with them.

This was getting harder to sustain, though. And fewer people seemed interested in holding onto it.

“The way of life is changing so bad,” Mr. Rose said. He grew quiet. “You’ll get overwhelmed if you think about it too hard.”

Jim Tankersley contributed research.

Campbell Robertson is a Reporter at The New York Times -- Greater New Orleans Area