Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: One Year in Washington

The corridors of Capitol Hill

are a marbled monotony, with Oxford heels clacking around corners indistinguishable from one another, white walls, oaken doors, and a steady rhythm of rectangular congressional nameplates.

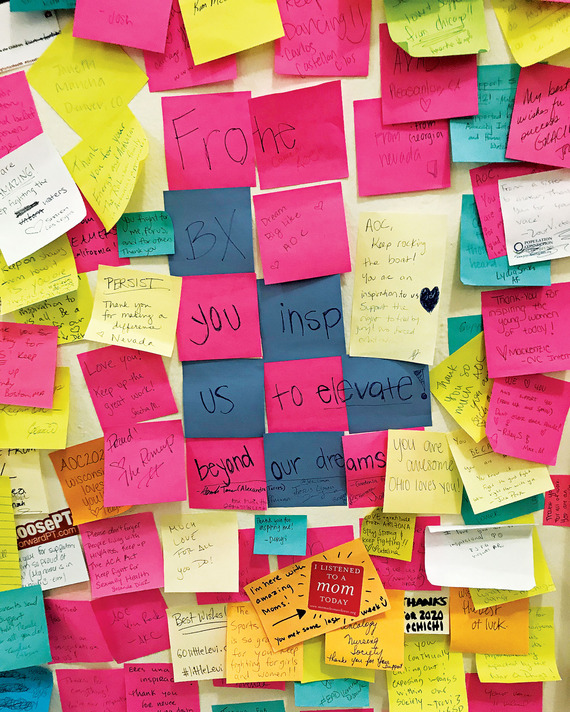

Except for one. At the very end of a hallway in Cannon Office Building is an explosion of affirmation cribbed onto thousands of Post-it notes, a neon-green-and-pastel-pink flower bursting outward. Go there at the right time, Hill aides say, and you can see groups of people, usually women, often young, weeping at the sight of it.

“I love you from Maine! Keep on with your fierce, informed queen of a self!,” wrote Mikala from Bangor on a pink Post-it. “AOC! Seeing you is seeing me! I live in Michigan, but you are my representative. Adelante!,” says one on white signed (with a heart) from Kristen on August 1. “Dear AOC. Continue to scare old white men,” adds another.

They go on and on and on, these paeans to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 30-year-old freshman member of Congress from Queens and the Bronx, who, in the year since she was sworn in as the youngest woman elected to the House of Representatives in the body’s 230-year history, has emerged as perhaps the most significant political figure in the Democratic Party in the age of Trump. She was recently ranked the fourth-most-tweeted-about politician in the world, beating out every Democrat running for president. It’s not that there is already a children’s book about her, The ABCs of AOC. It’s that there is already a comic-book series about her, a young-adult biography of her, a wall calendar of her, a book of her quotes, a collection of essays about her, and even, this holiday season, a Christmas sweater with her face on it.

Ocasio-Cortez’s staff didn’t know what to do with the Post-its when they first started appearing after she was inaugurated in January 2019. It seemed possible they broke a House rule — and if not an official violation, it was a practice that, at the least, would mark her as different from the rest of the incoming class. Staff took the first batch and framed them in her office, but the notes kept coming. If anyone writes something negative or nasty, one of the myriad devotees who make the pilgrimage takes the errant note down before it can spoil the mood.

Photo: Courtesy David Freedlander // New York Magazine

“It’s weird,” Ocasio-Cortez said when we spoke inside the Capitol Building one afternoon in mid-December as impeachment hearings consumed Washington. “Because I know I am also one of the most hated people in America.”

As the rest of the world has changed, Congress remains a place of traditions. Even the chaos merchants — the Ted Cruzes and Rand Pauls and tricornered tea-party Republican congressmen — still end up playing by the rules as laid out by the leadership. Ocasio-Cortez, at least so far, has not. She is at once a movement politician and a cultural phenomenon, someone equally at home on CSPAN and Desus & Mero. She isn’t especially interested in compromising with those who don’t share her values, and isn’t afraid to be the lone “no” vote, as she was last January, when she was the only Democrat to vote against funding the government because it meant continuing to fund ICE. Twelve months later, it is clear she isn’t trying very hard to amass power in Congress. Her heroes are Bernie Sanders, who withstood party pressure decade after decade in the Senate, and Howard Thurman, a mentor of Martin Luther King Jr.’s who believed in merging the spiritual and political.

“People come here, and they have served in state legislatures or they may have been executives for health-insurance or fossil-fuel companies or lobbyist groups or PACs, and they’re part of this whole club,” she said. She was dressed in all black — blazer, blouse, pants, and boots, looking more like someone about to cruise out of the last shot of a movie on a motorcycle than someone skipping out on a House Financial Services Committee meeting. “What is it like to show up to Congress with a beginner’s mind? You just fundamentally do things differently.”

The Democratic congressional majority, she told me, is too acquiescent to the demands of its members in so-called red-to-blue districts — those moderates who flipped Republican seats and gave Pelosi the gavel. “For so long, when I first got in, people were like, ‘Oh, are you going to basically be a tea party of the left?’ And what people don’t realize is that there is a tea party of the left, but it’s on the right edges, the most conservative parts of the Democratic Party. So the Democratic Party has a role to play in this problem, and it’s like we’re not allowed to talk about it. We’re not allowed to talk about anything wrong the Democratic Party does,” she said. “I think I have created more room for dissent, and we’re learning to stretch our wings a little bit on the left.”

Ocasio-Cortez isn’t the first politician to become a cultural sensation, but she may be the first to do so at the very beginning of her career, when she is occupying the lowest rung of political power. Her main project going forward may be this: harnessing her immense star power and the legion of young lefties who see her as their avatar, not just to push the Democratic Party away from an obsession with its most moderate members but also to make the stuff of government, like congressional committee hearings and neighborhood town halls, into must-see TV. She said the Congressional Progressive Caucus should start kicking people out if they stray too far from the party line. Other caucuses within the Democratic Party in Congress require applications, Ocasio-Cortez pointed out. But “they let anybody who the cat dragged in call themselves a progressive. There’s no standard,” she said.

The same goes for the party as a whole: “Democrats can be too big of a tent.”

It is comments like that that kept Ocasio-Cortez and the rest of the Democratic Party from reaching any kind of meaningful détente. I asked her what she thought her role would be as a member of Congress during, for instance, a Joe Biden presidency. “Oh God,” she said with a groan. “In any other country, Joe Biden and I would not be in the same party, but in America, we are.”

F

our days before Ocasio-Cortez won her primary in one of the biggest congressional upsets in at least a generation, I stood with her on a street corner in Queens, across from a bodega, underneath the 7 train, and not far from the housing project where she had been canvassing. Long-shot candidates for Congress tend to sound the same. They have a compelling bio, can lay out a theory of why they should win and how the entrenched incumbent has been absent or ignored community voices or kowtowed to the powers in Washington, but they often crumple under sustained questioning and have fantastic views of how politics works.

Ocasio-Cortez was different. She was a bartender who had come up through a network of post-2016 millennial activist groups and been recruited to run by the progressive PAC Brand New Congress 18 months earlier. As she went door-to-door, talking to voters, her answers came in mic-drop paragraphs. She saw politics as a rigged system that preserved the careers of those in power at the expense of the poor and working class. Her face that June was ubiquitous in the neighborhood, the result of her army of volunteers blitzing the district with palm cards and posters. Her time in the service industry seemed to make her an unusually empathetic listener. For the most part, here was someone who looked like her district’s voters, who spoke their language, who had come to ask for their support.

Congressman Joe Crowley’s polling had him up by more than 30 points. The weekend before the election, when typically campaigns go all-out with volunteers and visibility, Ocasio-Cortez skipped town — not something somebody who hopes to win an election does. She went to the border, where news was just emerging that the Trump administration was locking up migrant children and separating them from their parents. The visuals of the candidate, dressed in all white, pleading with border guards through a fence to remember their humanity, were striking. Two mornings later, Ocasio-Cortez woke up anonymous for the last morning in her life.

“I realized this was going to be a tattoo-on-my-face kind of situation,” she said. “I can’t go outside anymore. I miss being able to go out to dinner. I miss anonymity. I have to send my boyfriend out to get groceries. There has been a shift in chores.”

If she was a hero on the streets of New York and online, in Congress, “it was very, very chilly coming in,” she said. Joe Crowley was an old-school Irish pol who slapped backs and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for his peers. He was a conventional Democrat and congressman, and his replacement had tarred him as hopelessly compromised (for raising money from corporations and pharmaceutical interests); as a creature of Washington who lacked vision, courage, and a moral core. Would she do the same to her colleagues?

The fears of what Ocasio-Cortez would mean were present even before she was sworn in, when she swung by a sit-in in Speaker Pelosi’s office for the environmentalist group Sunrise Movement; she wanted the soon-to-be Speaker to push for a “Green New Deal.” Other members of “the Squad” — the group she created with Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib when she posted an Instagram of them together on orientation day — were supposed to join her but begged off, and even Ocasio-Cortez’s staff were on the phone with allies moments before, wondering if it was a good idea.

“I was terrified,” she told me. She doesn’t regret it — though it set the stage for a very complicated year with Pelosi. “I learned a lot about how fear shapes the decisions of elected officials: ‘I know this could be bad, and this could make someone mad, and I don’t know exactly how they would drop the hammer on me or what hammers would be dropped.’ It felt like the right thing to do, and when you say that people think it’s a form of naïveté and that it’s childish, but I don’t think it was.”

Ocasio-Cortez backed Pelosi for Speaker, but the two continued to battle publicly. It wasn’t just that they disagreed about policy: Pelosi thinks in terms of votes, of what any member can bring to the table and who they can bring with them. Preserving the Democratic majority means protecting the party’s most vulnerable members, those in places where people still like Donald Trump and the Democrat may have won by just a few hundred votes in the midterm — exactly the group that Ocasio-Cortez thinks the party doesn’t need.

That the freshman didn’t have a meaningful coalition behind her and had alienated some natural allies didn’t seem to give her pause. The Congressional Black Caucus, in particular, was put off by her association with Justice Democrats, the young campaign operatives — co-founded by Ocasio-Cortez’s then chief of staff Saikat Chakrabarti — who powered her win and have made it their mission to replace the Democratic Party’s moderates with a younger and more liberal group of lawmakers. Black lawmakers believed (not entirely incorrectly) that this meant the group was coming for some of them. In the press, CBC members accused Justice Democrats of being privileged gentrifiers with little respect for what it had taken them to gain political power.

The conflict came to a head in the summer of 2019, when Chakrabarti accused moderate members of the caucus on Twitter of acting like segregationist Democrats of the civil-rights era. Democratic leadership pounced online, suggesting that Chakrabarti was a racist for singling out lawmakers of color. After Donald Trump jumped into the fray (of course), Pelosi and Ocasio-Cortez had a closed-door meeting. Chakrabarti left soon after, as did another top aide, Corbin Trent, who had been with Ocasio-Cortez since the campaign. Pelosi has never spoken in public about what was said at the meeting; Ocasio-Cortez told me that the two staffers had planned to leave anyway. (They did not go far from her orbit, Chakrabarti to the progressive think tank New Consensus and Trent to her 2020 campaign.)

The fracas forced Ocasio-Cortez to ask, What does this movement look like, and what is my role in it?

“What was frustrating was getting singled out over and over again over a series of interviews by the Democratic leadership,” Ocasio-Cortez told me. She said that her colleagues consider her an unseen force in every primary this cycle, when in fact she has made endorsements in just two races. Meanwhile, it is the moderates who have put up more challengers to liberal incumbents than the other way around. “As a consequence of my victory, many people are inspired to run for office, and in a body where 70 percent of the seats are safe red or safe blue, that de facto means a lot more primaries. A lot of members think I’m like a Koch brother.”

House leadership sees the past summer as having been a turning point and believes that Ocasio-Cortez is now sufficiently chastened. She’s showed up for the job she was elected to do — coming prepared to committee meetings and hearings (like when she cornered Mark Zuckerberg on running misleading ads on Facebook), sponsoring 15 pieces of legislation (most notably the Green New Deal), and missing only two of 701 roll-call votes. I spoke with dozens of House and New York City governmental officials, some of whom disagree with her politics and have reason to dislike her personally, and they all said that she shows up to meetings unusually attentive, taking notes and asking detailed questions and writing personal follow-up emails. That even in House caucus meetings, as members call one another “Congressman this” or “Congresswoman that” but casually call her “Alexandria,” she gets to know her ideological enemies’ home lives and interests.

“There are people here who are never going to like her, never going to trust her, who are always going to be worried that she is going to turn her people against them,” says one House aide. “But you can’t say she isn’t making an effort. I think people are surprised at how not-strident she comes off.”

Still, even Democrats who are supportive of Ocasio-Cortez’s political project wonder how much enthusiasm there will be for it during an election year. It is one thing to reform a party out of power; it is another when the party is trying to unify for the most consequential election year in memory. Dissident factions could prove deadly to Democratic efforts to retake the White House. Should the party succeed, even with (very optimistically) a slight majority in the Senate, the chances of getting anything passed could easily get bogged down in partisan infighting.

“No one gets all of his or her way,” Congressman Gregory Meeks, Crowley’s replacement as head of the Queens Democratic Party, told me recently. “You have to learn quickly; otherwise, you will be in the minority and you will be as relevant as that windowpane. Do you want to be able to just talk a lot or do you want to be able to do something?” If you are a hard “no” in Congress, eventually people will stop asking for your vote. You don’t need to be negotiated with because everyone already knows the answer, and — most of the time — this means your voice is marginalized.

Ocasio-Cortez’s opponents in the Democratic Party want this to be her fate. “This is how it works here: You negotiate a concession in exchange for a vote. But you have to have the votes and you have to be willing to negotiate,” says one House aide friendly to Ocasio-Cortez. “She says she is an organizer, but you have to be willing to organize in the caucus as well as outside it.”

Opponents point to the fact that early in her tenure, rather than using her prodigious public influence to push for a climate bill that had 71 co-sponsors and would have kept the country in the Paris climate accords, she unveiled the Green New Deal. A draft of the resolution was mistakenly released early, and critics jumped on vague language in it to accuse the new congresswoman of wanting to ban beef and air travel and to give free money to people who don’t work.

But it is still the biggest achievement of her term, a rebuke to the idea that leverage is the only power in town. The Green New Deal, for all its vagueness — it was a resolution and a statement of principles and not a piece of legislation — set up a new tentpole in the debate. More than a hundred Democrats signed on as co-sponsors, including a handful of moderates whom House progressives have been trying to push left for years, as did every major contender for the Democratic presidential nomination, including Joe Biden.

“The most ambitious climate plans were a carbon tax here or a biodiesel thing there. There were no climate bills that were a solution on the scale of the problem. I couldn’t take all of this and say, ‘Let’s get a 10 percent subsidy on electric vehicles,’ ” Ocasio-Cortez said. “These very small incremental plans are a form of denialism.”

Photo: David Williams for New York Magazine

Late last month,

Politico reported that some political operators are already speculating that Ocasio-Cortez will run for president in 2024 or 2028, and it has been a topic of conversation among her advisers as well. After decennial redistricting in 2020, Ocasio-Cortez could find herself drawn into the district of a neighboring member of Congress, where the young agitator’s odds would suffer. People close to her discussed a possible run for mayor of New York in 2021 but decided against it; a statewide run, probably for the Senate, is likelier. That would mean challenging Chuck Schumer in 2022 or Kirsten Gillibrand in 2024.

She and her advisers are aware of her almost unprecedented situation: a wildly popular woman of color with the confidence of Pete Buttigieg, if not his demographic advantages. If she ran for president, they say, she would run to win, not to carry the banner of her brand on behalf of the progressive movement and come in second.

Ocasio-Cortez told me how much she admires Bernie Sanders. (She was, by her own estimation, “a scrub” on his 2016 campaign, going door-to-door in the South Bronx.) Year after year, he was willing to be the lone vote on issues that mattered to him, withstanding the pressures to play along with the rest of the team on health care, on taxes, on wages. Eventually, the party caught up to him. Every senator running for president except Amy Klobuchar has signed on to his “Medicare for All” bill. The party is debating a wealth tax, something floated by Ocasio-Cortez on 60 Minutes last year and now pushed by both Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

It is clear there is a shift happening in American politics, one that favors Ocasio-Cortez’s long-term prospects. Trump’s demagogic populism is a part of it, and so is the fact that Americans ages 18 to 24 are more favorably inclined toward socialism than capitalism, that 80 percent of young people think the federal government should address climate change, that over 70 percent say the wealthy should pay higher taxes, and that some of the highest percentages ever recorded call their politics far left or liberal. Post-millennials are majority nonwhite in 13 states and in nearly 40 percent of the nation’s largest metro areas; they are close to majority nonwhite nationwide. Sanders leads by large margins among the young, but also fares better than almost any Democrat against Donald Trump — proof, perhaps, of millennials’ desire for someone liberal and the heartland’s desire for different political ideas.

And Ocasio-Cortez is all of these things: Latina, liberal, “authentic,” fluent in social media and popular culture. Outspoken lefties have come and gone before, but often they were like Bernie or, before him, Ralph Nader: rumpled, grouchy, hectoring. For leftists, politics used to be something to avoid, a corrupting drag on the purity of activism. Ocasio-Cortez has changed that.

“You hear that trope all the time. ‘I am a workhorse; I am not a show horse.’ But what I think people don’t understand is that educating the public is a part of this job. The most effective public servants are part of our culture. They are just as fluidly part of the conversation as Lizzo or as this movie that you saw,” she said. A few days after our interview, at a middle school in Woodside, Ocasio-Cortez hosted her 12th town hall of the year, one for every month, not including the dozens she has attended that were hosted by others. She points to these town halls, along with directing $500 million in federal grants to her district, as examples of what she’s done for her constituents this year. She had attended a breakfast with Bronx veterans in the morning, SantaCon was raging outside, it was cold and miserable, and her boyfriend, Riley Roberts, was waiting in the wings. But she had to be on. At her town halls, fans, who line up for hours for selfies, often present her with shrines they’ve made to her: paintings of her, T-shirts, family keepsakes. At the one in December, when they finally reached the front of the selfie line, some of her fans just started cheering: “Yea! Yea! Yeaaaaa!” The congresswoman gamely tried to keep up.

Photo: T.J. Kirkpatrick/The New York Times/Redux; Sarah Silbiger/The New York Times/Redux; Courtesy CNN. // New York Magazine

This is part of

her project, too. If people are paying attention, she figures, they will be on her side. “Politics should be pop because it should be consumable and accessible to everyday people,” she said. “I think that’s what populism is about.”

Her vision extends beyond Congress. After the election, two of her top campaign aides founded a program called Movement School designed to teach the next generation of campaign operatives what they learned from pulling off the upset of the decade. About 70 people have gone through the ten-week training camp, and they are spread out all over the country — a standing army of dedicated campaign staff that will only grow in the years ahead.

Ocasio-Cortez is still in regular contact with leaders of the Democratic Socialists of America, and she has quiet dinners with the volunteers who worked on her campaign, the people who called her Alex until they were told, after the election, that it would be better if they stuck to Alexandria — dinners in which they promise to not Instagram anything with her. So far, no one has.

That whole crew will be put to use before long. The reelection bid has already attracted a dozen challengers, including a conservative Democrat pastor, a city councilman close to the Bronx machine. Her team — hyperaware of not taking primary challenges for granted — is preparing to use the race to build out her presence on the ground, talking to voters about her vision of a political revolution, and convincing those who may be skeptical why having a political supernova as their representative is actually useful. There has been no public or private polling on the race, but according to her campaign, Ocasio-Cortez is expected to have raised $5.3 million in 2019 alone, and she’s influential locally. Her endorsement nearly propelled a left-wing neophyte named Tiffany Cabán into the office of Queens District Attorney (she ended up losing to a favorite of the county party by 55 votes), and local electeds have rushed to bask in her celebrity. Her opponents will tag her with having killed jobs by torpedoing the Amazon deal, and argue that she’s more consumed with her own celebrity than the needs of her district; her campaign will counter that, say, her effort to abolish ICE is central in a district where half the population was born in another country. She is setting up a campaign office that will be used as a “space for political education, a kind of ‘TED Talks for activists’ ” program running between now and November.

“Everyone in the House is just constantly thinking about self-preservation, and we don’t get nice things because people are constantly thinking in electoral terms. The way we change that is through political education. I had this conversation with Bernie,” she said. “Here’s this guy in a then-Republican state, a quite conservative state, and he wins by a handful of votes to become mayor of Burlington. And by the time he becomes senator, Vermont is crazy-blue. And a lot of that has to do with his time there. And I said, ‘So how’d you do this?’ And he said that he and different grassroots movements in Vermont spent decades doing political education. And they took on the long-term project of turning a red state blue.”

As political analysis goes, this is a bit specious. Vermont turned blue thanks to a number of sociological and demographic factors greater than any single politician. But it’s also the kind of downfield vision more likely to be expressed by people who work in political organizing than inside the government. It explains a lot about how she acts in Congress. By the time Ocasio-Cortez is as old as Bernie is now, the year will be 2067. The Democratic Party may have immediate needs, but she wants the movement to think in longer time frames.

“Republicans have focused on that long-term project for a very long period of time. Democrats don’t. We think if something is red, it stays red. But you know what? I think if a state like Tennessee or West Virginia can go from blue to red in our lifetime, I think it can go back,” she told me. Justice Democrats are taking aim at another dozen or so incumbents this cycle; if a few more get in, she could build a bloc. “That’s a kind of project that a lot of people think is a waste of time, but I don’t think it is,” she said.

“This whole primary,” she went on, referring to the one Biden and Bernie are in, “is going to be about the soul of the Democratic Party. I think it’s a referendum on whether we think everything was fine before Trump. People who live in a lot of privilege, who think of public programs as charity, they often think there was nothing wrong before Trump. They think Hillary was the problem. But it’s much deeper than that.” And so, on the eve of a primary contest that will train everyone’s attention on the project of unseating the president, Ocasio-Cortez is keeping her focus closer, betting that a purer, bolder Democratic Party is the one this country wants, and can afford.

*This article appears in the January 6, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!