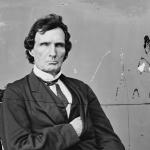

Thaddeus Stevens, Revolutionary

If Abraham Lincoln was, in historian James McPherson’s apt words, a “reluctant” revolutionary, Thaddeus Stevens was an eager one. “There was in him,” Frederick Douglass said of the Radical Republican and Pennsylvania congressman, “the power of conviction, the power of will, the power of knowledge, and the power of conscious ability,” qualities that “at last made him more potent in Congress and in the country than even the president and cabinet combined.”

An ardent believer in the “free labor” capitalist society then developing in the US North, Stevens strove throughout his life both to assist that economic system’s growth and to rid it and the nation as a whole of “every vestige of human oppression” and “inequality of rights.” At the national level, he worked above all to outlaw the ownership of human beings that was central to the economy, social relations, and politics of the Southern states. Accomplishing that task, he well knew, would be a huge undertaking. It would require radically transforming Southern society, stripping the wealthy planter class of both its most valuable property and the source of its social authority and political power.

Ruling classes, however, do not surrender their wealth and power willingly, passively, or peacefully. Slave state leaders verified that historical truth by launching an armed rebellion after his antislavery party, the young Republican Party, won the presidential election of 1860. When that rebellion led to war, Thaddeus Stevens, by then a Republican leader in the House of Representatives, was one of the first to grasp the conflict’s implications and the requirements of defeating the pro-slavery forces.

Although others in his party attempted to achieve a military victory by restricting the Union to cautious, conservative methods and goals, Stevens emphatically opposed them. “We must treat this as a radical revolution,” he insisted, because “ordinary means cannot quell this rebellion” or “prevent its recurrence.” Only bold and radical measures striking at the very foundations of the slavery-based South — and the implementation of those measures with the kind of “ardor which inspired the French revolution” — would accomplish that.

In Service of the Revolution

In the wartime US Congress, Stevens fought for strong antislavery and antiracist laws and policies, measures that Abraham Lincoln and others would only come around to later. He was one of the first to call for freeing Confederate slaves and was among the first to insist on the need to recruit black men, free and slave, into the Union’s previously lily-white armies. He pushed for the permanent abolition of slavery — not only in the rebellious states but throughout the United States — a year before Lincoln endorsed that idea.

When the South was finally defeated, Stevens saw in the ensuing tasks of “Reconstruction” an opportunity to bring the country’s laws and government into fuller accord with the Declaration of Independence’s assertion of human equality. He demanded civil and political rights for African Americans, urging the federal government to use all the force at its disposal to defend and enforce those rights against white-supremacist terrorism. (They were eventually codified in the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, whose enforcement the modern Civil Rights Movement would demand a century later.) When Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, allied himself after the war with the South’s white elite in order to restore and reinforce white supremacy, Stevens pushed the House to impeach the president. Only the resistance of more conservative Republicans in the Senate prevented the Radical Republican from getting his wish.

Although trained as a lawyer, Stevens was not especially concerned with staying within the four corners of the law or even the Constitution. His north star was the needs of the revolution. He justified confiscating Confederate property and slaves, for instance, by arguing that the seizures were necessary to suppress the planters’ rebellion. Whether an action was moral or immoral, he argued, depended upon the ends that it served and on the particular context in which the action occurred. Stevens was not rejecting morality as a guide. But he held that whether an action was moral or immoral depended upon the ends that it served, on the particular context in which the action occurred. Implicit in this line of thinking, of course, was a belief that an appropriate end dictates and justifies the means needed to achieve it.

Then and now, this claim is commonly deplored in the name of absolute standards of right and wrong that transcend time, place, and circumstance. But Thaddeus Stevens considered his own, more practical, understanding of the relationship between ends and means both irresistible and unassailable. His was the same moral compass that revolutionary forces throughout history have commonly utilized.

Stevens found legal support for his approach in “the laws of war,” as explicated by the eighteenth-century Swiss scholar Emer de Vattel. The United States was in a fight for its very life, Stevens argued, invoking Vattel, and it was obliged to do whatever was necessary for victory. But when the war itself was won, Stevens simply modified his argument. Having suppressed the rebellion and begun emancipation, the Union must secure its wartime accomplishments and continue “perfecting” the republic by ensuring equal rights for all, black and white. That goal was the sole standard against which the rightness or wrongness of government action must be judged.

Some worried that such reasoning could also justify tyranny. Stevens responded by directing attention back to the specific ends being sought in each case. That was the way to evaluate the legitimacy of the means being justified. Thus, he noted, both the wartime Union and the leaders of the pro-slavery rebellion claimed extraordinary governmental powers. Must we judge both sets of claims to be of equal merit, Stevens asked. Of course not, he continued. We uphold one claim and reject the other because of the very different ends that each actually serves. In the Union’s case, he said, extraordinary “power is granted for good,” while in the Confederacy’s case, extraordinary power is “seized for mischief.”

Stevens’s ends-based argument reappeared in his impeachment crusade against Andrew Johnson. While the Pennsylvania representative occasionally gave lip service to the narrow framework of other Republicans — who claimed that to be impeached a president must violate a specific law — Stevens’s core motive for trying to remove Johnson from office was not that he was a lawbreaker. Nor was Stevens animated by his personal distaste for the man, although Stevens had indeed come to despise Johnson. (When another congressman tried to excuse the president on the grounds that he was, after all, “a self-made man,” Stevens replied acidly that he was “glad to hear it, for it relieves God Almighty of a heavy responsibility.”)

But at bottom, Stevens was far less concerned with punishing a villain or penalizing past crimes than with clearing a path for future positive action. As with the extraordinary measures that he had championed during the war, that is, Stevens shaped his Reconstruction policies with less concern for the formal legalities involved than for the ends he deemed urgent.

He thus told his party’s caucus in early January 1867 (according to a reporter’s summary) that Republicans needed to impeach Johnson because “it was impossible to reconstruct the South with Andrew Johnson as President.” When a Democratic congressman denounced impeachment’s motives as political, Stevens agreed. The fight to oust Johnson, he readily acknowledged, was “wholly political” in purpose — it was, in other words, indissolubly bound up with a struggle over government policy. Johnson’s removal was necessary for the implementation of policies that would “protect . . . the liberty and happiness of a mighty people” and “take care that they progress in civilization and defend themselves against every kind of tyranny.”

Thaddeus Stevens’s Radical Proposal

More conservative members of Stevens’s party not only blocked Johnson’s impeachment. They also killed one of the congressman’s most radical and potentially transformative initiatives.

After the war, Stevens called upon the federal government to confiscate lands owned by the Southern elite and give them to former slaves as small farms. Doing so, he argued, would provide at least a measure of justice to the “four millions of injured, oppressed, and helpless men, whose ancestors for two centuries have been held in bondage” and forced to perform the labor that paid for the land in question. Creating and safeguarding a democratic society, Stevens argued further, demanded such a measure. “It is impossible that any practical equality of rights can exist,” Stevens explained in the fall of 1865, “where a few thousand men monopolize the whole landed property.” For “how can republican institutions, free schools, free churches, free social intercourse exist in a mingled community of nabobs and serfs?”

As a party floor leader in the House of Representatives whose initially unpopular proposals had often proved essential, Stevens had won great authority among many fellow Republicans. But very few of them were willing to follow his lead on this issue. Just one day after Stevens introduced a land-reform bill, the House overwhelmingly rejected it. More than two-thirds of the Republicans who voted (including even some members of the party’s radical wing) joined Democrats in opposition, and another ten Republicans abstained.

Why? Because most Republican leaders — staunch champions of “free labor” capitalist society — refused to cancel the private-property rights of plantation owners. The challenge of treason and armed rebellion had eventually reconciled them to the abolition of a form of property — human property — that they already considered illegitimate and even sinful. But they balked at infringing, especially in peacetime, upon claims to another form of property — private property in land — that remained as close to their hearts as ever. Many also feared that if black farmers were granted land, they would refuse to use it to grow cotton (a crop so closely associated with slavery), thereby harming New England’s important textile firms.

More broadly still, Republican leaders and their business-backers worried that redistributing property to assist exploited and impoverished people would set a dangerous precedent, one that might encourage similar demands in the North. After all, warned the Republican New York Times, calls to seize property and give it to the poor posed “a question . . . of the fundamental relation of industry to capital.” So “if Congress is to take cognizance of the claims of labor against capital” in this case, then “sooner or later, if begun at the South, it will find its way into the cities of the North.”

A Boston editor expressed similar anxiety. Attacking landed aristocracies, he wrote, “is two-edged,” since “there are socialists who hold that any aristocracy,” including the North’s own economic elite, is anathema. Stoking these fears among capitalists and their newspaper allies was an unprecedented wave of labor organizing and worker strikes in the North that was just then cresting.

The same aversion to labor radicalism would later fuel Northern Republicans’ turn against Reconstruction as a whole, thereby leaving freed people to the tender mercies of a reinvigorated and vengeful Southern white elite. As a result, the fight to further democratize US society was thrown back, and the Second American Revolution was left unfinished.

Democratizing America

In his last year of life, 1868, Thaddeus Stevens already thought he saw that outcome on the horizon. Suffused with gloom, he told a writer that his principal “regret is that I have lived so long and so uselessly.”

Others, however, held his achievements in higher regard. Some who did so could not yet foresee the defeats that lay ahead. Others, because they understood that such defeats would not be total, that key achievements — especially the abolition of outright slavery and all that implied — would endure. And still others, because they believed that the gains that survived and the example that Stevens and other radicals had set would help future generations to reconquer lost ground.

The Civil Rights Movement of the twentieth century did accomplish some of that. But the task of genuinely democratizing US society — especially by doing away with all forms of racial discrimination and oppression and assisting those victimized by it to overcome its powerful and poisonous legacy — remains before us. The kind of dedication and boldness that Thaddeus Stevens displayed in his lifetime will serve us well as we undertake that work.

Bruce Levine is the J. G. Randall Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois. Simon & Schuster will publish his latest book, Thaddeus Stevens: The Making of a Revolutionary, in January of 2021.

Jacobin is a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture.