At this particular moment, the most-watched show in America is a seven-part documentary series about a gay, polygamous zoo owner in Oklahoma who breeds tigers, commissions and stars in his own country-music videos, presides over what he describes as “my little cult” of drifters and much younger men, and ran for governor of Oklahoma in 2018 on a libertarian platform. He’s also currently serving a 22-year prison sentence for, among other charges, trying to arrange the assassination of his nemesis, an animal-sanctuary owner in Florida. And his business allies include another big-cat breeder—a yoga-loving guru in Myrtle Beach who runs what appears to be a tiger-themed sex sect.

In that sense, Tiger King is also the latest and most acute iteration of a Netflix trend toward extreme storytelling; the more unfathomable and ethically dubious, the better. The point is virality—content so outlandish that people can’t help but talk about it. In 2018, the docuseries Wild Wild Country Abducted in Plain Sight Love Is Blind and the upcoming Too Hot to Handle , a show in which ridiculously good-looking people are sequestered on an island to compete for a cash prize that diminishes every time they hook up, or even masturbate. The more scurrilous or degrading the concept, the more we watch.

This truism wasn’t news for P. T. Barnum, and it isn’t news now. But there’s still something wretched to me about the way Tiger King has managed to define a cultural moment in which empathy and communitarianism are so crucial. America right now, in the midst of a pandemic, is reliant on collective behavior, adhering to rules, and taking sensible precautions to avoid danger. Tiger King is the TV equivalent of licking the subway pole. Its characters have managed to construct whole worlds around themselves rather than curtail their worst impulses in any way. These characters are so colorful that they obliterate everything else around them. They’re any documentarian’s dream, and yet you can’t help but wonder what the directors hope to get out of giving showmen the mass exposure that they want. Who, in the end, benefits?

On its face, Tiger King is about a remarkable subculture in the U.S.: people who collect and (illegally) breed big cats. There are, the show reveals early on, more privately owned tigers living in America than there are existing in the wild, kept in independent “zoos” and parks across the country. (In 2003, authorities discovered that a man in Harlem was cohabiting with a 400-pound tiger named Ming, in the same apartment that his mother was using to babysit children.) If the people drawn to tigers have a shared quality, Tiger King emphasizes, it’s extroversion, which it illustrates in one scene with footage of Doc Antle riding an elephant into town while opining in voice-over about the “primordial calligraphy” of exotic animals.

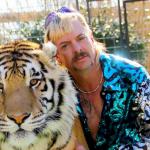

Joe Exotic, for better or worse, is the show’s central character, and Tiger King sketches out a sparse biography that hints at, rather than elucidates, the forces that shaped him. The challenge seems to be that anything he says is stated in the service of inflating his own mystique, and the directors decline to press him or any of the other characters on the worst charges against them. There are some undeniable facts, such as how hard it must have been for Exotic to be a gay man in rural Oklahoma during the ’80s and ’90s. There’s also his history of releasing country songs he only lip-synchs to; his run for president in 2016 and for governor two years later; and his habit of filming virtually everything he does. There are a few private moments, too, including how he reacts after one of his employees is mauled by a tiger while at work. “I’m never gonna financially recover from this,” Maldonado-Passage sighs, while the rest of his employees try to tend to the victim’s severed arm. Hardest to endure is how he behaves at the funeral for his youngest husband, Travis, who accidentally shoots himself in the head. Dressed up in a dog collar, Exotic seizes the spotlight, singing, cracking jokes, and reminiscing fondly about his late partner’s testicles while Travis’s mother sobs.

Mostly, though, Exotic communes with tigers. He cuddles them while they’re riding shotgun in the front seat of his truck; he wrestles with them; he uses a steel hook to wrest newborn cubs from their mothers and then complains that the screaming babies are making too much noise. The visual impact of seeing humans and tigers so intimately connected is one of the defining qualities of Tiger King , and is also, the series suggests, why some people find tigers so appealing. There’s a taboo quality to the breach of natural laws separating humans and big cats that implies strength, virility, and power. No wonder, the show notes, so many male Tinder users have tiger selfies as avatars.

Tiger King ’s unified theory of tiger obsession falls short, however, when it reaches Carole Baskin, the owner of a Florida animal sanctuary devoted to big cats. This shortcoming might explain why the show takes such pains to portray her as a kook, and possibly even a murderer. Baskin is Exotic’s bête noire, a woman who has dedicated her career to trying to outlaw the breeding and personal ownership of exotic cats in the U.S. The show’s treatment of Baskin is where it indulges in its most egregious displays of false equivalence, as it tries to elevate her eccentricities to stand alongside those of Exotic and Antle. Baskin, Tiger King painstakingly lays out, is obsessed with animal print. The horror! Sometimes she wears flower crowns! She has an uncanny gift for search-engine optimization! She rides a bicycle! Her sanctuary relies heavily on unpaid volunteers! The show underscores all these facts, while making the most of the mysterious disappearance of Carole’s husband in 1997 and interviewing family members who seem convinced that she killed him. “There is absolutely no physical evidence at this time” implicating any one individual as a suspect, a police detective firmly and rather crushingly points out. Tiger King doesn’t care. It would much rather imply several times that she could have fed her husband’s corpse to tigers, had she been so inclined.

Baskin is interesting, too, because she’s a woman operating in a world characterized by gleeful misogyny. Exotic makes effigies of Baskin; he fills her mailbox with snakes (a strangely phallic gesture); he makes memes about her crotch, and videos in which he fantasizes about torturing her with a horse penis. He calls her a bitch so many times that the word loses all meaning. Jeff Lowe, one of Exotic’s business associates, who enters the series midway through, is a more limited character, but his treatment of women is still horrible enough to be noteworthy. (As his wife tells the camera about how she’s preparing for the upcoming birth of their child, Lowe remarks that she’ll immediately have to go back to the gym, and shows the directors glamour shots of the women he’s considering as nannies. Lowe, according to the show, also has a felony criminal record and a history of charges that include throttling his first wife .)

The degradation in Tiger King starts to feel contagious after a while. Goode and his co-director, Rebecca Chaiklin, filmed the series over five years, and the longer they spend with their subjects, the more obviously things fall apart. One of Exotic’s ex-husbands, John Finlay, gives shirtless interviews that show off his abundant tribal tattoos—including a crotch adornment that reads privately owned joe exotic—and his undeniable lack of teeth. (Only in Episode 5 does Tiger King stop to note that meth has been a prevalent factor in Exotic’s world the whole time.) The interviews become more and more invasive. Travis’s mother is asked about her son’s death while she’s seemingly intoxicated. In Episode 7, one of Exotic’s zoo employees is so incapacitated that he passes out mid-interview. Exotic’s campaign manager is interviewed early on as a fresh-faced former Walmart manager enthusiastically crafting Exotic’s libertarian platform; a year or so later, he too has lost teeth, and appears considerably more disheveled than during his clean-cut canvassing days.

Exotic is the only one who appears unchanged, even as the plot makes its way toward his 22-year jail sentence for conspiring to have Baskin assassinated. The persona he’s crafted, you sense, is strong enough to survive anything, even prison. In that sense, there’s something undeniably Trumpian about him. No misfortune can shake his sense of self. No humiliation can shame a man who refuses to be shamed. The chaotic reactions that Exotic has sparked are irrevocable, and even now, he’s fast approaching cultural-legend status, as Hollywood stars spar on Twitter over who gets to play him in the already-approved miniseries. “Fuck yeah, roll the cameras,” is how the reality-TV producer Rick Kirkham described watching Exotic at his most idiosyncratic and badly behaved. Netflix obviously agreed. Why can’t the rest of us look away?

Sophie Gilbert is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers culture.