“We Need You to Fight for Us to Breathe”

Say their names: Breonna Taylor. Ahmaud Arbery. George Floyd. Tony McDade. David McAtee. Manuel Ellis.

Some days it’s hard to breathe. Here’s my truth:

I’m a Black mother raising Black kids.

My son, Javonte, joined the U.S. Marines at 17 because he wanted to make a difference, he wanted to serve his country. He came home five years later only to witness his country condone and sanction the continued murder and abuse of Black men who look like him. He won’t tell me he’s scared; he doesn’t have to.

My daughter, Jasmyne, is a freedom fighter, always has been. As her mom, I encouraged that fire; taught her to stand up for what she believes in, defend others, and use her voice to speak truth to power. Some days I worry I’ve failed her, that I haven’t prepared her for the times she will need to give that power away so she can come home safe. She won’t tell me she’s angry, she doesn’t have to.

My daughter, Niah, is graduating from high school this year, she has her whole future in front of her and has carefully planned every year step. Like her dad, she’s always on time and is a dedicated list maker and planner. She recently told me she’s not sure she wants to have children because she knows they’ll be born Black, and the world is too cruel to Black boys and girls. She won’t tell me she’s sad, she doesn’t have to.

I’m a wife, married to a strong Black man.

My husband, Marcus, doesn’t share his fears openly or freely, but I know he never does more than five miles over the speed limit. I watch him make sure our cars are well maintained so the police won’t have cause to pull us over and so we don’t end up broken down alone on the side of the road where he can’t help us. I’ve listened to him have “the talk” with our kids more than once. He won’t tell me he worries; he doesn’t have to.

I’m a Black woman leader in the labor movement.

I spend my time working in systems and structures not designed with me in mind. The diplomacy and code shifting required to navigate these systems is sometimes exhausting, knowing I carry the hopes and dreams of my ancestors and the voices of my community into every space, every conversation, every decision. Some days the weight makes it hard to breathe. I won’t tell you I’m tired, I don’t have to.

Here is the truth:

The system isn’t broken. The system is operating exactly the way it was intended to.

We have lost so many of our sisters, brothers, and siblings to white supremacy; COVID-19 is ravaging BIPOC communities that are already systematically under-resourced and over-policed. Against the backdrop of a pandemic already wreaking havoc on Black communities, these recent, public murders of Black Americans are sickening. While they may be shocking to some white Americans, this is the America that Black folks have always lived in – the America that I have always lived in.

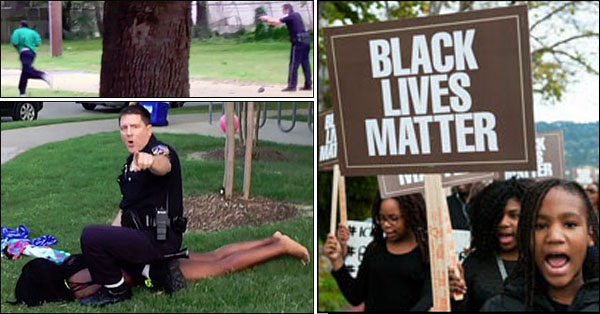

While the prevalence of camera phones fundamentally changed the conversation around policing in America, in fact, what we are witnessing is a steady stream of modern-day lynchings in real time. Lynching is defined as a murder committed in public by three or more perpetrators, for the purpose of punishing an alleged crime without a trial. Eric Garner was lynched. Michael Brown was lynched. Philando Castille was lynched. Charleena Lyles was lynched. George Floyd was lynched. And while laws may shield them from consequences, it was police who lynched each of these Black Americans and our governments that sanctioned these murders.

Policing in America is too often violence, disproportionately directed at Black communities. There are clear, systemic causes leading to the hyper-policing of Black bodies. We are not experiencing a mass psychosis affecting police departments across the United States. Rather, this police violence, primarily targeting Black Americans, is the system of policing operating as designed.

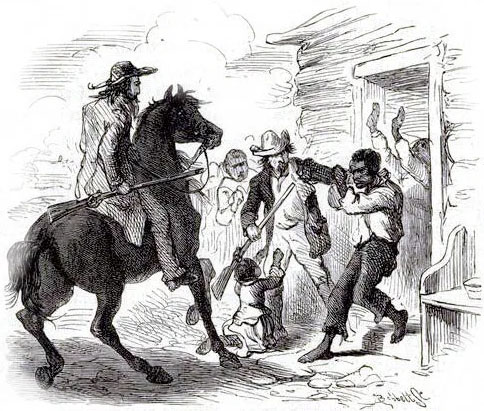

Furthermore, we know that policing was born out of slave patrols, consisting primarily of white and poor men paid by landowning elites to return escaped Black folks to the brutality of slavery for their capital gain. With emancipation, Southern legislators passed laws empowering these same poor whites to curtail the free movement of formerly enslaved Black folks, attempting to recreate the subjugation of slavery. Black people, previously covered by slave laws, were now living under the same legal codes that whites lived under; thus, new crimes were created to control Black Americans. White supremacy is at the core of policing in America.

And let’s not forget that ultimately, white supremacy was designed and is upheld even today to divide working people. We see this from the very beginnings of this country. The Virginia Slave Codes — which denied certain rights to all Black people enslaved or not, explicitly creating racist differentials in treatment intended to sow discord amongst working people — were passed as a direct response to Bacon’s Rebellion, an uprising where working people of all races banded together against wealthy landowners. White supremacy is at the root of our institutions, planted there intentionally.

And while we can find examples throughout our history of white Americans combating white supremacy — white clergy joining the Freedom Summer, for example — overturning and reshaping white supremacist institutions requires more than some well-intentioned accomplices.

White supremacy provides a ruse of racial superiority that is progressively fooling fewer and fewer people. We’re recognizing what actually limits us as working people: the concentration of the wealth our labor produces in the hands of bosses and billionaires at the expense of our families and communities.

As that consciousness rises, none of us have the privilege of waiting to confront police violence. While Black folks disproportionately face the brunt of police violence, no one is immune. Black folks are canaries in the coalmine, often the first to be subjected to oppression. Collectively, our society has allowed abusive policing in historically disenfranchised communities of color. This failure has allowed unaccountable, increasingly militarized policing to become the norm in all our communities, as we’ve seen all too clearly in the past week. Anyone that threatens the power structures that police were created and exist to protect is a threat.

At our best, organized labor — with our belief in the humanity that each of us share with one another, with our commitment to solidarity with all working people, to bettering the conditions of all of us — is a movement focused on our common power as working people. This solidarity with all working people across race is a direct threat to white supremacy.

We should be proud to be that threat; but more than that, we need to put it in action.

As Frederick Douglass lamented, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never has, and it never will.” Policing cannot reform itself. The politicians that have empowered unaccountable police forces cannot reform the system. And as policing is built explicitly out of attempts to control Black people, we must question if police can be reformed at all, or if rather, we need to entirely re-conceive what policing looks like.

If we’re going to live out our commitments as unionists, we need to remake policing to uphold our ideals. This requires action from all of us. Historically, protest movements have been successful in fundamentally altering the course of this country when they channeled the energy on the streets into the halls of power. We can do our part supporting this work by ensuring we elect good partners who will fight for and win needed policy changes.

This means when we’re electing officials who back working people — and ensuring they remain accountable — we need to be clear we’re talking about all working people, including Black people.

If elected officials don’t fight for Black people, they don’t fight for any of us. If they can’t unequivocally say that Black lives matter, then they don’t truly believe the lives of working people matter. And if they don’t back us, we’ll vote them out of office.

In Seattle in the past few days, we’ve seen police armed to the teeth on the same streets where only months ago nurses marched demanding the bare minimum in safety protections and respect on the job. Police in body armor are well-equipped to fight people exercising their constitutional right to protest while medical professionals across the state have been begging for the PPE they need to fight COVID-19. Think of how twisted our system must be if we’re prepared to arm people for murder, but not to save lives.

Black Americans need our allies in labor to show up for us. This violence sits on us most heavily but it is not on us to fight it alone. We need our siblings in the movement to hear our truth, to do the uncomfortable but necessary work of fighting the white supremacy that is choking us. We need you to fight for us to breathe.

April Sims is Secretary Treasurer of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO, representing the interests of more than 600 union organizations with approximately 550,000 rank-and-file members.

To learn more about the formation of race as a tool to divide working people, check out Race to Labor: Can Organized Labor Be an Agent of Social & Economic Justice? on our website. For more on the origins of policing and white supremacy in our criminal justice system, check out The New Jim Crow by Michele Alexander. To learn more about the epidemic of police violence in America, check out The Washington Post’s database of police shootings, and mappingpoliceviolence.org.

The Stand is a service of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO (WSLC) and its affiliated unions, The Stand was launched on May Day 2011 to restore the kind of progressive populist source of information that once thrived in our state, but has disappeared thanks to media consolidation and corporate influence on the press. The Stand features news about — and for — working people. Its reports and opinion columns focus on creating and maintaining quality jobs, improving our families’ quality of life, promoting public policies that will restore shared prosperity, and other things that the rest of us care about.