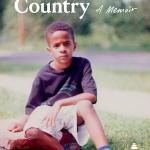

A Voice from America’s Black Belt

My Vanishing Country

A Memoir

Bakari Sellers

Amistad

ISBN: 9780062917454

IN 2006, AT JUST 22 years of age, Bakari Sellers was elected to the South Carolina General Assembly as a Representative in the House, following that up with a run for lieutenant governor before he was 30. Now 35, Sellers is a practicing attorney and CNN analyst on race and politics in the United States. Somewhere on the horizon, there’s a run to represent the people as a member of the United States Congress. But wherever his ambitions may eventually lead him, Sellers says that he is “never far from home” — that is, Denmark, South Carolina, where, he writes in My Vanishing Country: A Memoir (already a New York Times best seller), beauty and blight and history are intertwined.

In February 1968, Harry K. Floyd, owner of the All-Star Bowling Triangle Bowl in Orangeburg, South Carolina, drew ire and protests for his continued refusal to serve black patrons. All-Star was an opportunity — “a flashpoint for desegregation,” Sellers says. His father, Cleveland Sellers Jr., was among the protesters fired upon by the highway patrol. Some were killed. The Orangeburg Massacre captured the attention of Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson, and the NAACP.

Cleveland Sellers was shot, arrested, and then imprisoned under conditions of hard labor for the better part of a year. “The injustices that occurred that night left my sister to be born when her father was in prison,” Sellers writes. “My sister’s middle name is Abidemi, which means ‘born while father is away.’” One of his father’s biggest regrets, he believes, is that he first met his daughter while inside the Columbia Correctional Institution. Closed for years, All-Star Bowling is now a historic site in the fight for black civil rights, included on the National Register of Historic Places. “There are scars from the movement that many people and their families still deal with today,” Sellers says.

My Vanishing Country revisits that painful history, as well as the triumphant spirit that compelled him to follow his father’s path of civic leadership. Sellers writes that, even before he was even in kindergarten, “my father was taking me along to various community meetings and academic conferences.” “Bakari,” in Swahili, means one with great promise — one who will succeed. His longtime friend Jamil Williams, affectionately known as “Pop,” saw Sellers’s charisma and his skills at debating when they were kids. Sellers’s father’s course and his own, he writes, “are tangled together over the same bloody ground,” with an aim to heal this divided nation. “I’ve geared my life towards understanding who I am and fighting against systemic oppression and injustices,” the author tells LARB. “I don’t play the games of respectability politics that some of my colleagues do,” he adds. Systemic injustices demand a deep dive — not a drive by.

Denmark is about 20 miles southwest of Orangeburg. It’s a small town with a long memory. Growing up there was a unique experience, Sellers recalls. “Everybody knew I was Cleve Sellers boy. Everybody knew our name.” Though his father received a pardon years later, Sellers was known as the child of an agitator, a rabble-rouser’s kid. “Some people are afraid of you,” he says. “Some give you chances.”

Sellers’s “not-so-distant ancestors toiled over cotton, indigo, sugarcane, rice, wheatgrass, and soybeans,” enriching slaveholding families and their descendants. After emancipation, the swift divestment of whites created property devaluations and inequities still evident today. “In the South, especially around the coast, we’re uniquely in touch with this history,” Sellers says, reminding us that some of the first African slaves put to labor in what would become the United States were in Charleston, South Carolina, not 100 miles from Denmark.

In Denmark, which sits along the Black Belt, “the nation’s largest contiguous thread of poverty,” the population is 93 percent black and the average income is around $30,000 per year. “We, people of color, black folks, especially black folks in the South, we built this country for free and now we’re having to fight for our basic humanity,” the author laments. “Many times, we’re just fighting for a seat at the table down here because, for far too long, we’ve been on the menu.”

In spite of the scarcity and anxiety, and the relentless struggle for equality, Sellers says there was always a special togetherness in Denmark. “Even though we were a very poor community, we were a part of fortune,” he says.

Cleveland Sellers had been a Boy Scout. He’d grown up solidly middle class. But his many accomplishments, including scholarships that led to a career as an educator, made little difference in the Jim Crow South, and his criminal history threatened to hold him back. “All of my father’s opportunities came from relationships,” Sellers says. People looked out for the Sellers family.

“Growing up in a country that has a hard time loving you, my faith is oftentimes put to the test,” Sellers says. “But with that sense of community, everybody had a hand in raising you.” This organic collective wealth that thrives even in deprivation is the irony of Denmark, and it’s what Sellers writes so warmly about in My Vanishing Country.

Michael Eric Dyson, Tyler Perry, Charlamagne tha God, and Hillary Clinton have all praised My Vanishing Country, believing the book to be important, especially now, for the spirit of the nation. Asked about plans for the big screen, Sellers says that conversations are already underway. “I would love for J. D. Washington to play me,” he says, speaking of the star of BlacKkKlansman, the son of Pauletta and Denzel Washington.

Sellers’s memoir comes at a critical time when the disparities affecting black America are in plain view. “We can’t analyze the disparities of today’s COVID-19 without talking about historic injustices,” Sellers says. “Food deserts, lack of access to quality care and clean drinking water, brownfields, air pollution. All of these things lead to preventable illnesses and comorbidities in our community.” My Vanishing Country gives context, voice, and honor to the everyday heroic lives of the American Black Belt.

¤