Illinois - Slave State

Because Illinois is a northern state and the former home of Abraham Lincoln, it isn’t typically associated with slavery. But there was slavery in Illinois for more than 100 years.

Even after Illinois entered the Union, loopholes in its laws allowed the practice to continue, making the future Land of Lincoln a quasi-slave state.

Essay - While Abraham Lincoln lived in Illinois, he never lived in a free state. The Great Emancipator’s home had slavery from the early 1700s until 1863, two years before Lincoln died. There were even slaves in his town of Springfield.

“Illinois has ever been a synonym of liberty, enterprise and progress…(yet) our own State once tolerated slavery,” wrote Ethan A. Snively in the 1901 Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society. For a time, “Illinois was as absolutely a slave State as was Mississippi.”

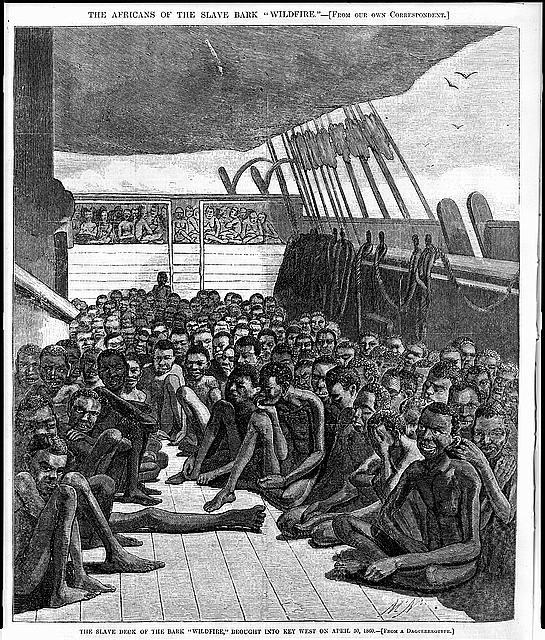

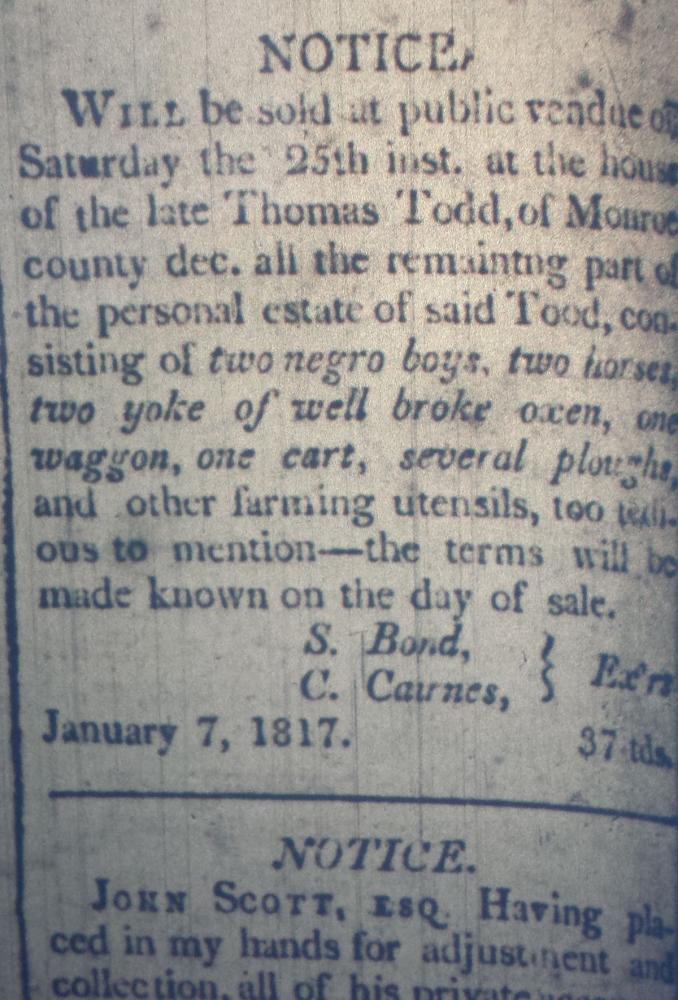

“No attempt was made to conceal the traffic in slaves,” according to the 1904 book, “History of Negro Servitude in Illinois,” by N. Dwight Harris. “Frequent notices of desirable negroes ‘for sale’ and ‘wanted’ appeared in the Western Intelligencer (newspaper) of Kaskaskia.” Slave auction notices appeared there, too.

Blacks were held here as chattel, or in perpetual servitude. They were taxed as property, given as gifts and used in Shawneetown’s salt mines and Galena’s lead mines. They were auctioned to the highest bidder and captured by professional kidnappers who sold them back to the south.

We know this partly from servitude and emancipation records at the Illinois State Archives in Springfield, which document the sale, auction, transfer and emancipation of both Native American and black slaves. We know this from the ads searching for runaway slaves and promoting slave catchers’ services in newspapers. Lastly, we know this from our state’s contradictory early laws and settlers’ stories.

Africans brought to Key West in April of 1860

CREDIT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Blame the French for bringing the peculiar institution to the state, but blame Illinoisans for perpetuating and increasing it.

In 1719, French businessman Philip Frances Renault brought 500 slaves from “San Domingo” to develop a mine near Fort Chartres, which is now Prairie du Rocher in southwestern Illinois. It failed, so Renault sold his slaves to residents and left, according to Harris’ book.

Slavery remained legal under subsequent British rule but things got trickier when Illinois land became part of the U.S. Northwest Territory in 1787. Although the Northwest Ordinance outlawed slavery and “involuntary servitude,” territorial leaders decided it meant that new slaves couldn’t be introduced here, but existing ones could remain enslaved.

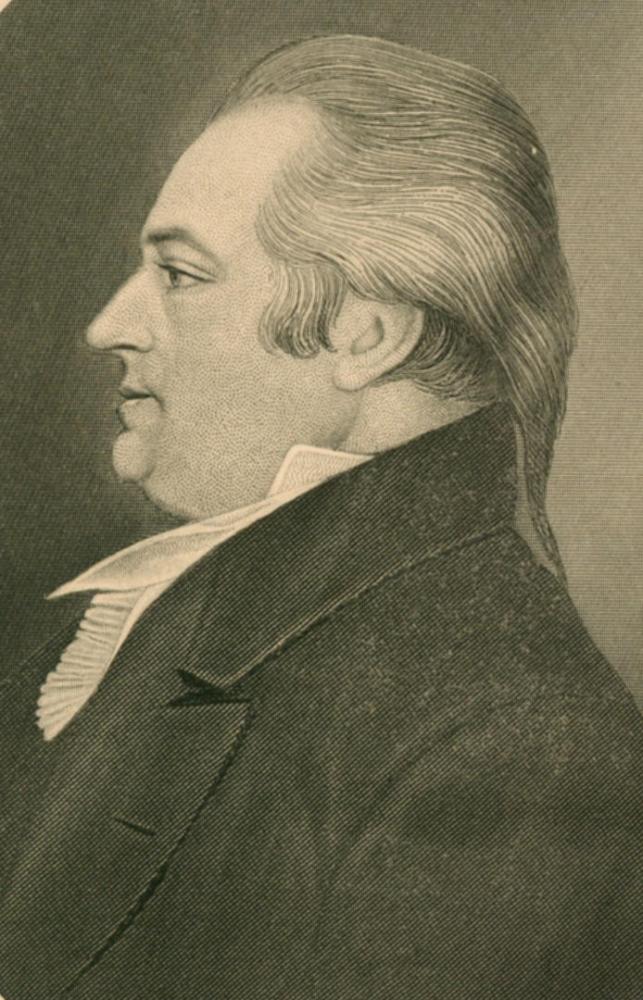

Illinois, first territorial governor, slave owner and lawyer Ninian Edwards, whose slave-owning son of the same name became Lincoln’s brother-in-law in Springfield, decided that the Ordinance allowed for so-called “voluntary servitude,” where a black person could “voluntarily” contract with a white person to work for a specified period. “It was a way around the slavery question,” says Illinois State Historian Sam Wheeler. “Some of those contracts didn’t last the traditional seven years, but 99. So it was basically slavery under another name.” That name was indentured servitude.

Ninian Edwards, Illinois' first territorial governor, held slaves and thought the practice of indentured servitude was "not repugnant" to the public.

CREDIT THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

Edwards believed that indentured servitude was “reasonable…, beneficial to the slaves and not repugnant to the public,” according to Harris’ book. He even skirted the law to force at least one of his slaves, who was just a baby, to work for him longer. Male children born to territory slaves could only be enslaved for 30 years, by law. But “the law was…evaded by registering the children of colored servants for thirty-five in place of thirty years of service on the ground that they were not born in Illinois,” wrote Harris. “A case in point is Ninian Edwards’ Joseph, whom he registered…to serve thirty-five years. Joseph was then eighteen months old, and had just been brought into the territory with his mother. All this the masters did knowingly, believing, quite rightly, that no one would take the trouble to prosecute them for holding their slaves to unlawful service.”

With this laissez-fair attitude about enslavement, it’s no surprise that Illinois’ slave population increased almost five fold while it transitioned from a territory to a state, according to federal censuses. In 1810, Illinois had 168 slaves; in 1820, it had 917, making it “the only Northern state to show an increase in slave population” during that time, wrote Mark W. Sorensen in the 2003 Illinois Heritage magazine.

When Illinois earned statehood in 1818, the U.S. government required that it be a free state. So, Illinois followed the country’s lead: The state outlawed it, but still allowed it. “Illinois didn’t invent slavery; it didn’t invent the fundamental contradictions about it,” Wheeler says. “It reflected America.”

Illinois’ first Constitution stated that “slavery and involuntary servitude” could not be “introduced” in the state, except as criminal punishment. But it required that already indentured slaves in Illinois be “held to their contracts,” and it legalized the use of slaves in southern salt mines. In another twist, it required gradual emancipation, stating that indentured servants be freed at age 21 for males and age 18 for females. This was “a gesture to anti-slavery residents,” according to Christopher P. Lehman’s book, “Slavery in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1787-1865.”

Like the southern states, one of the reasons Illinois allowed slavery was economic. “The majority of the (Illinois) people were pro-slavery,” wrote Snively in the 1901 Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society. “They desired immigration from the slave states – they recognized slavery and wealth as synonymous. So long as there was uncertainty as to property right in slaves, so long there would be no immigration from slave states.”

Other reasons, according to Harris’ book, were: slaves were needed to settle the land, having slaves here would decrease the chances of a slave riot by dispersing them around the country, and “it would provide the colored people with a partial escape from the servitude of the south by the possibility of a transfer to the lighter indentured servitude system of Illinois,” and thereby be “an inestimable blessing to blacks.”

Most of Illinois’ slaves were in the southern part of the state because Illinois was settled from the south up. Many of the first settlers came from southern states and were slave owners or at least pro-slavery; those that had slaves wanted to keep them. The majority of the state’s early leaders were the same. Four governors owned slaves. As long as Illinois leaders were pro-slavery, the state’s laws were, too.

Illinois wasn’t the only northern slavery state, however. Indiana’s 1816 state Constitution outlawed slavery, but it, too condoned indentured servitude for a few decades. “Illinois was an outgrowth of Indiana,” explains Wheeler. “That’s where Illinois got the concept (of indentured servitude).”

For a northern state, however, Illinois might have had the worst slavery record. The state was the only one in the upper Mississippi Valley, which included Illinois, Iowa Minnesota and Wisconsin, whose Constitution allowed slavery and indentured servitude, says Lehman. “What other states tended to do was to say that they are going to have their states become free states, but they won’t allow free African-Americans to live there.”

Illinois didn’t go quite that far, but it got close.

One year after Illinois’ Constitution was created, the state’s legislature passed some of the worst “black codes” in the country, according to many accounts. These laws made coming to or living here very difficult for blacks. The codes were based on “the presumption that if you’re an African-American, you are enslaved,” says Wheeler. The penalties for disobeying them “resembled those of slave states and slave-labor plantations,” writes Lehman.

While Illinois’ black codes didn’t directly relate to slavery, they communicated its citizens’ main message to African-Americans: “Stay away.” They also affected runaway slaves who traveled to Illinois, which many did when escaping to freedom in Canada via Illinois’ active Underground Railroad.

By 1845, Illinois’ slave population had increased to nearly 5,000, according to Roger Bridges’ article in the 2015 Fall/Winter Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. By this time, an increasing number of free blacks had established homes in the state as well. Perhaps not coincidentally, Illinois intensified its black codes.

Those laws prevented blacks from being in Illinois for more than ten days, or else they could be arrested, fined repeatedly and auctioned. Free blacks and their children had to show certificates of freedom and register with the county shortly after their arrival in Illinois. “Slaves or servants” had to have written permission to travel more than ten miles from their master’s homestead or risk whipping. Blacks couldn’t gather in groups of three or more to dance or make “revelry,” or they could be lashed. And, to perpetuate their enslavement, blacks couldn’t vote or testify in court.

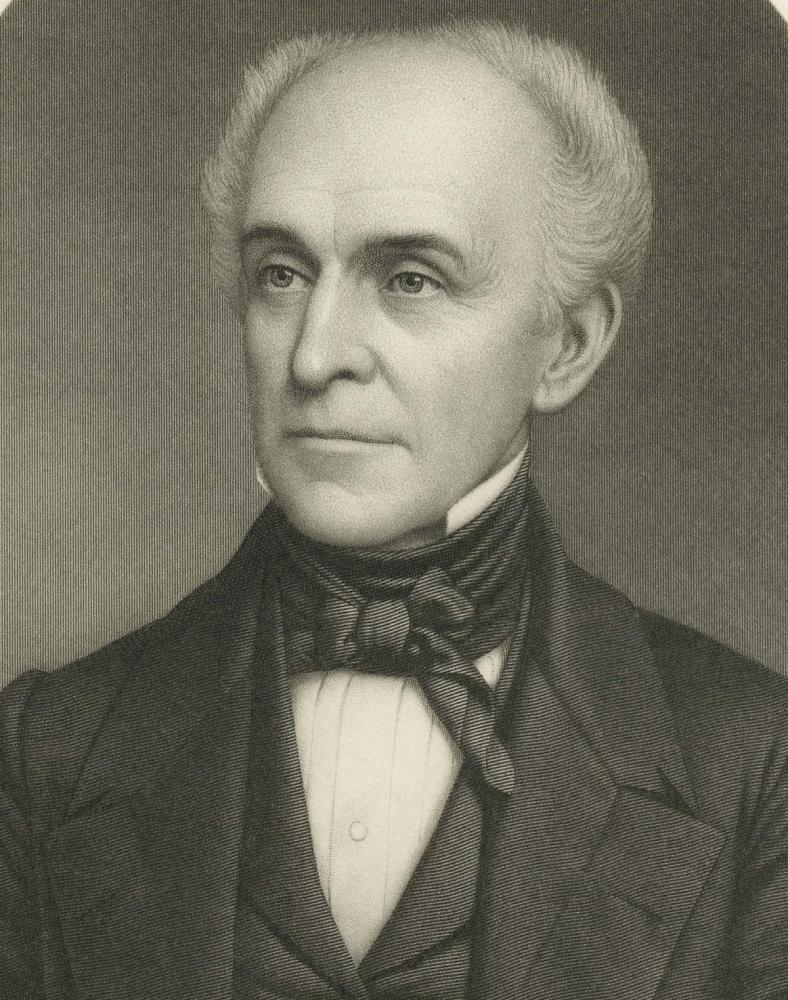

Edward Coles, the state's second governor, inherited slaves in Virginia but freed them in Illinois, which was against the law.

CREDIT THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

Despite its mostly pro-slavery stance, there were Illinoisans who fought the system, even in its early days as a state. The second governor, Edward Coles, migrated from Virginia, where he inherited slaves. Defying Illinois law, he freed them here and, thanks to lawsuits that went to the state’s supreme court, was eventually spared punishment for the crime. Coles advocated for a new constitution that would truly abolish enslavement here.

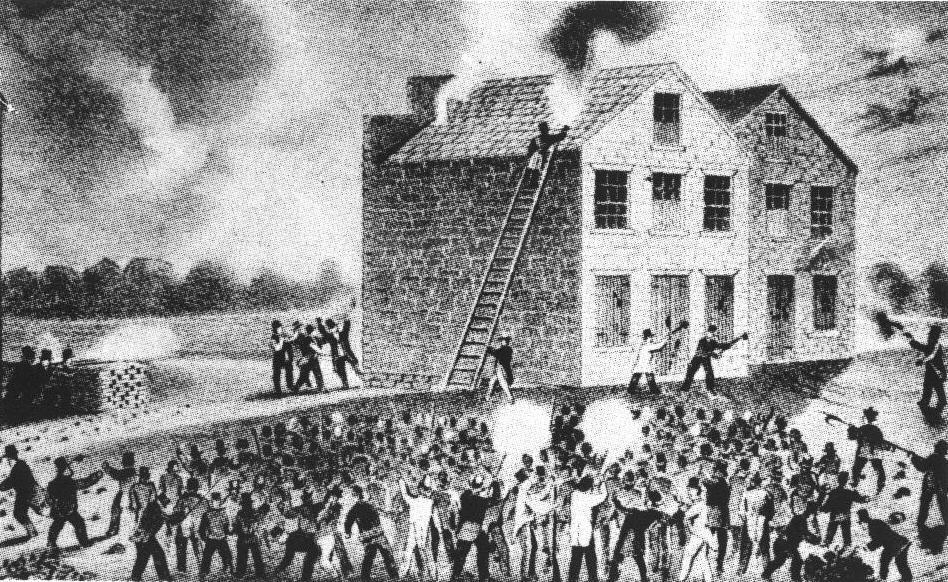

Slavery proponents seized on the call for a new constitution as an opportunity to solidify Illinois as a true slave state. Between 1822 and 1824, Illinois’ pro and anti-slavery factions warred over the issue. After a bitter election that drew an extraordinary number of voters, the pro-slavery contingent lost. Still, it kept fighting. One abolitionist lost his life to the group. Elijah Lovejoy was murdered in Alton in 1837 by a pro-slavery mob because he published an anti-slavery newspaper. Others like him throughout the state risked their lives by helping runaway slaves flee to Canada or escape kidnapping.

A pro-slavery riot in Alton led to the death of abolitionist and newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy.

CREDIT THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

“There are many documented cases of kidnapping (of blacks) in southern Illinois during the early nineteenth century, some recorded indictments, but almost no convictions…” writes Darrel Dexter in his book, “Bondage in Egypt: Slavery in Southern Illinois.” He contends that the state’s laws encouraged the practice. An 1819 state law mandated that citizens interrogate blacks to determine if they were free or runaway slaves. If they were the latter, the white interrogator received a monetary award.

Catching a runaway and returning the person to the south could be prosperous. Dexter tells the story of William Belford, Jr. a notorious southern Illinoisan from Pope County who made a living as a slave hunter. It was a family business. The Belfords earned as much as $300 for one runaway.

Free blacks were prey, too. Those who lived in southern Illinois especially children, “were constantly under threat of kidnapping,” according to Dexter. In 1824, Governor Edward Coles called for anti-kidnapping laws and the legislature complied, but the laws generally weren’t enforced. “Some kidnappers were so bold in southern Illinois that they rode up to the cabins of free African-American families and forcibly carried the children away,” Dexter writes.

Although Illinois’ new Constitution of 1848 outlawed “slavery and involuntary servitude,” slavery continued, but probably on a very limited basis. Records from the State Archives show the last recorded emancipation of an Illinois slave was in 1863, in the middle of the Civil War. Despite Illinois leading the call for soldiers to fight the war over slavery, anti-black sentiment here remained strong. “Just because people in Illinois opposed slavery doesn’t mean they necessarily endorsed equality among the races,” says David Joens, an Illinois historian and director of the Illinois State Archives. “That’s a big difference, and you see that in 1862 with the proposed new constitution.”

In the middle of the war, Illinoisans were asked to vote on a new proposed state constitution and three amendments that would add the black codes to it. They rejected the proposed constitution, but “overwhelmingly” approved the black codes provision, Joens says.

A notice in the January 22, 1817 Western Intelligencer of Kaskaskia

CREDIT THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

Three years later — while its own onerous black codes were still in effect, Illinois lead the country in approving the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which its favorite son, Abraham Lincoln, had penned to abolish slavery throughout the land. It didn't repeal its black codes until February 7, 1865, one week later.

Though the number of slaves in Illinois was small when compared to southern slave states, the legacy of slavery is interwoven in racist attitudes that plague the state and the nation, says Ronald Bailey, who is head of the department of African American Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“The impact of slavery in Illinois has to be seen as a much bigger issue than just the number of enslaved Africans who lived and worked in Illinois,” he says. “It’s clear to me that part of the contemporary trouble we’re having with worsening race relations that gets captured in the Black Lives Matter movement and reactions to that, have to do with whether or not people fundamentally believe that human beings are equal. We have such a legacy of people of African descent being treated unequally. I think that’s seeped into the way we handle issues of racial inequality in a way that we have not come to grips with.”

Bailey says Illinois’ history of slavery may be difficult for its residents to accept. But he says it’s important for Illinoisans to recognize this part of the state’s past and the ramifications that are still with us today — which we all share a responsibility to address. “It’s been hard for people to admit that this democracy, that this great nation … had some of its most important roots in a system that was as oppressive and exploitative as the slave system. And folks can very easily sweep that under the rug and say, ‘my folks weren’t slave owners. Therefore, that’s not something we should we concerned with today.’”

Tara McClellan McAndrew -- I've been a freelance writer for twentysomething years and have worked in a variety of media: radio, print, children's literature, plays, and documentaries. Although I was a theater major for a time, I got my bachelor's degree in English and my master's degree in public affairs reporting.

My professional life began at the National Public Radio station in my hometown of Springfield, Illinois where I covered state government. Yes, with a state as corrupt as Illinois, the job was never dull.

Even so, I branched out and covered other topics. I had pieces produced on Illinois Public Radio, National Public Radio, and Christian Science MonitoRadio, and I helped produce pieces for the BBC, Soundprint, and Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

My articles have been printed in: The Hollywood Reporter, Chicago Tribune Magazine, Back Stage, Illinois Issues, Christian Parenting Today, Cobblestone, Odyssey, and dozens of other publications.

But some stories are best told on stage. I've written five full-length plays and several one-act scripts; more than half were commissioned by historical sites or agencies, including: Lincoln's Home National Historic Site and the Looking for Lincoln Coalition, among others. All of my scripts have been produced.

In the last ten years, I've specialized in writing about history, especially the history of central Illinois and Abraham Lincoln. You might say both are a part of me. My roots grow deep in central Illinois and my ancestors knew Springfield, Illinois' greatest export personally. One opposed Lincoln in court and the other borrowed money from him. Everybody wants ties to Lincoln, but these weren't exactly what I was hoping for. They do make good stories, though.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.