‘Amazing, Isn’t It?’ Long-Sought Blood Test for Alzheimer’s in Reach

A newly developed blood test for Alzheimer’s has diagnosed the disease as accurately as methods that are far more expensive or invasive, scientists reported on Tuesday, a significant step toward a longtime goal for patients, doctors and dementia researchers. The test has the potential to make diagnosis simpler, more affordable and widely available.

The test determined whether people with dementia had Alzheimer’s instead of another condition. And it identified signs of the degenerative, deadly disease 20 years before memory and thinking problems were expected in people with a genetic mutation that causes Alzheimer’s, according to research published in JAMA and presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Such a test could be available for clinical use in as little as two to three years, the researchers and other experts estimated, providing a readily accessible way to diagnose whether people with cognitive issues were experiencing Alzheimer’s, rather than another type of dementia that might require different treatment or have a different prognosis. A blood test like this might also eventually be used to predict whether someone with no symptoms would develop Alzheimer’s.

“This blood test very, very accurately predicts who’s got Alzheimer’s disease in their brain, including people who seem to be normal,” said Dr. Michael Weiner, an Alzheimer’s disease researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study. “It’s not a cure, it’s not a treatment, but you can’t treat the disease without being able to diagnose it. And accurate, low-cost diagnosis is really exciting, so it’s a breakthrough.”

Nearly six million people in the United States and roughly 30 million worldwide have Alzheimer’s, and their ranks are expected to more than double by 2050 as the population ages.

Blood tests for Alzheimer’s, which are being developed by several research teams, would provide some hope in a field that has experienced failure after failure in its search for ways to treat and prevent a devastating disease that robs people of their memories and ability to function independently.

Experts said blood tests would accelerate the search for new therapies by making it faster and cheaper to screen participants for clinical trials, a process that now often takes years and costs millions of dollars because it relies on expensive methods like PET scans of the brain and spinal taps for cerebrospinal fluid.

But the ability to diagnose Alzheimer’s with a quick blood test would also intensify ethical and emotional dilemmas for people deciding whether they wanted to know they had a disease that does not yet have a cure or treatment.

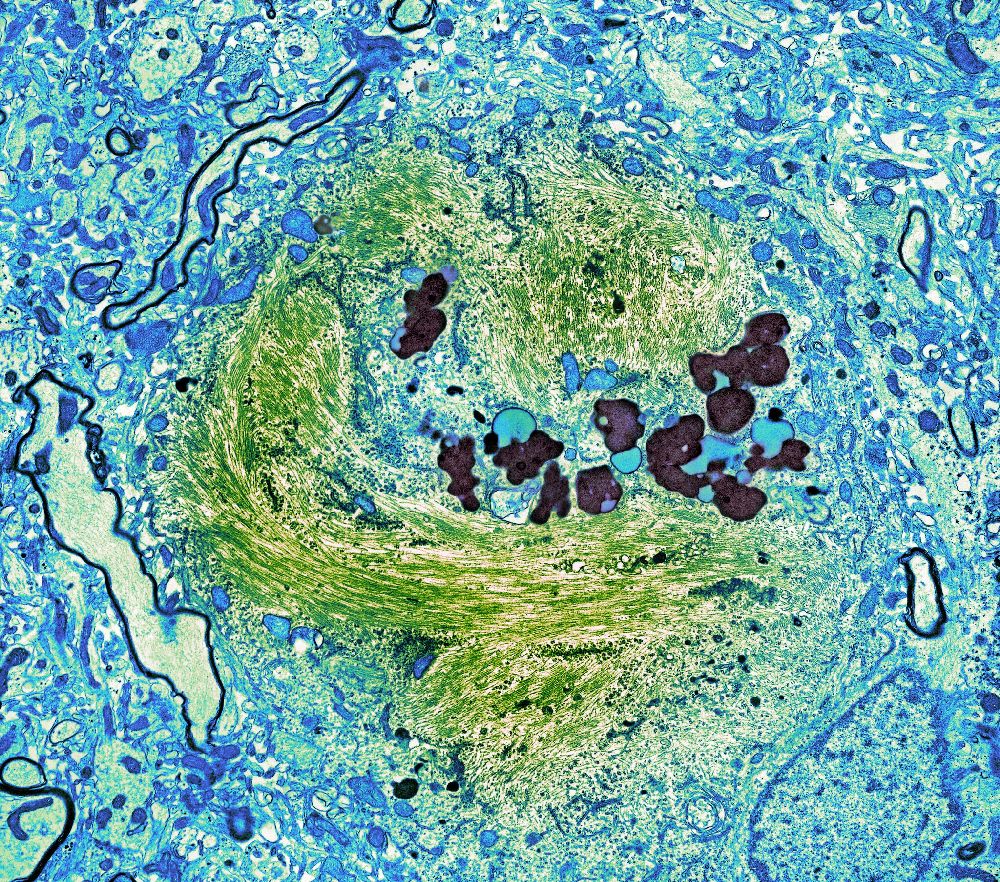

The test, which measures a form of the tau protein found in tangles that spread throughout the brain in Alzheimer’s, proved remarkably accurate in a study of 1,402 people from three different groups in Sweden, Colombia and the United States. It performed better than MRI brain scans, was as good as PET scans or spinal taps and was nearly as accurate as the most definitive diagnostic method: autopsies that found strong evidence of Alzheimer’s in people’s brains after they died.

“Based on the data, it’s a big step forward,” said Rudolph Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the research.

He and other experts said that the results would need to be replicated in clinical trials in more populations, including those reflecting more racial and ethnic diversity. The test will also need to be refined and standardized so results can consistently be analyzed in labs, and will need approval by federal regulators.

Currently, Alzheimer’s diagnoses are made mostly with clinical assessments of memory and cognitive impairment, as well as interviews with patients’ family members and caregivers. The diagnoses are often inaccurate because doctors have trouble distinguishing Alzheimer’s from other dementias and physical conditions that involve cognitive impairment.

Measures like PET scans and spinal taps — costly and often unavailable — can detect elevated levels of amyloid protein, which clumps into plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, and there has been recent progress on blood tests for amyloid. But amyloid alone isn’t enough to diagnose Alzheimer’s because some people with high levels don’t develop the disease.

“Just saying you have amyloid in the brain through a PET scan today does not tell you they have tau, and that’s why it is not a diagnostic for Alzheimer’s,” said Maria Carrillo, chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Association. By contrast, the tau blood test appears to register the presence of amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both of which are in brains of people with confirmed Alzheimer’s, she said.

“This test really opens up the possibility of being able to use a blood test in the clinic to diagnose someone more definitely with Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Carrillo said. “Amazing, isn’t it? I mean, really, five years ago, I would have told you it was science fiction.”

A newly developed blood test for Alzheimer’s measures a protein called tau which forms tangles in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s, like the green strands in this slide of a brain cell.Credit...Thomas Deerinck, NCMIR/Science Source

The test was 96 percent accurate in determining whether people with dementia had Alzheimer’s rather than other neurodegenerative disorders, said Dr. Oskar Hansson, a senior author of the study and a professor of clinical memory research at Lund University in Sweden. That performance, in a group of nearly 700 people from Sweden, was similar to PET scans and spinal taps, and it was better than MRI scans and blood tests for amyloid, another form of tau and a third type of neurological biomarker called neurofilament light chain.

People with Alzheimer’s had seven times more of the tau protein, called p-tau217, that the test measured than people without any dementia or those with other neurological disorders, like frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia or Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Hansson said.

“This is so specific for Alzheimer’s disease,” he said.

The study also compared findings of brain autopsies of donors from Arizona with test results on blood that they donated before they died. It found the blood test was 98 percent as accurate in diagnosing Alzheimer’s as autopsies of people found to have had a high likelihood of the disease because they had both amyloid plaques and extensive tau tangles in their brains, said Dr. Eric Reiman, another senior author and the executive director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix. The test was 89 percent as accurate as autopsies of brains that contained plaques but had fewer tau tangles and were considered moderately likely to have had Alzheimer’s, he said.

And in over 600 members of the world’s largest family with genetic early-onset Alzheimer’s, the test essentially identified who would develop the disease 20 years before dementia symptoms would surface. In this extended family in Colombia of about 6,000 people, some have a mutation that causes cognitive impairment beginning in their mid-40s. The test could distinguish between those with and without the mutation in people as young as 25.

The most immediate uses of blood tests would be to speed up and lower the cost of clinical trials and to allow doctors to diagnose or rule out Alzheimer’s in patients with dementia if they and their families sought that information to help them plan for what lay ahead.

“The certainty of a diagnosis could help patients, family caregivers and physicians themselves cope,” Dr. Reiman said.

And, Dr. Tanzi said, in the future blood tests might be given to people without any impairment, perhaps as initial screening tools to be followed with PET scans if worrisome levels of biomarkers were detected.

“It has the promise to make early detection of the disease possible, before we have symptoms,” Dr. Tanzi said, something the field would only recommend for clinical use if there were effective ways to prevent or treat Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Hansson said his lab was studying whether the test could predict dementia in people with no impairments or those with mild memory problems.

The test in the JAMA study used a method called an immunoassay to detect compounds that bind to antibodies. Several such assays are being developed. The particular assay in the study was developed by Eli Lilly and Company, which provided materials and three employees to conduct the assays; the company was allowed to review the manuscript but not veto anything in it, the authors reported. Most of the funding for the study came from government agencies and foundations in Sweden and the United States.

At the Alzheimer’s Association conference, Dr. Hansson and a co-author, Dr. Kaj Blennow, presented their findings, as did two other research teams working on tau blood tests.

One test, developed by a team at Washington University in St. Louis that included Dr. Randall Bateman, Dr. Suzanne Schindler and Nicolas Barthélemy, used a method called mass spectrometry, which detects entire molecules of tau or amyloid. In a study published on Tuesday in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, that team found that the same form of tau in the JAMA study, p-tau217, correlated more closely to amyloid buildup in the brain than another form, p-tau 181, that some researchers have been focusing on. Dr. Schindler, an assistant professor of neurology, said that might be because p-tau217 emerges earlier in the Alzheimer’s disease process.

In another study presented at the conference, Dr. Adam Boxer, a neurologist at U.C.S.F., and Elisabeth Thijssen, a visiting graduate student, used the same immunoassay in the JAMA study and found both forms of tau could distinguish Alzheimer’s from frontotemporal dementia, showing how specific these proteins are for detecting tau associated with Alzheimer’s, Dr. Boxer said.

Several researchers are working with companies or, like Dr. Bateman and Dr. Reiman, have formed their own. Ultimately, various methods may be approved for medical use. Dr. Carrillo said mass spectrometry had the advantage of relying on a machine that was already in use, but the disadvantage of being more expensive and requiring more expertise than immunoassays, which are easily analyzed by laboratories that routinely run blood tests.

“Within a few years, it’s very possible that there will be certified laboratory tests for these proteins and others, and maybe tests will be developed for Parkinson’s disease and so forth,” Dr. Weiner said. “It’s a new world.”

Pam Belluck is a health and science writer whose honors include sharing a Pulitzer Prize and winning the Nellie Bly Award for Best Front Page Story. She is the author of Island Practice, a book about an unusual doctor. @PamBelluck