A Disputed Election, a Constitutional Crisis, Polarisation … Welcome to 1876

As Donald Trump warns inaccurately of voter fraud and polls show the unpopular president staying within touching distance of Democrat Joe Biden, the prospect of an unresolved US election draws horribly near, especially as the impact of the coronavirus is widely seen as likely to delay a result by days, if not weeks.

Across the political spectrum, pundits are predicting what may happen should Trump refuse to surrender power. The speculation is tantalising but the short answer is that nobody has a clue.

History does provide some sort of guide. There have been inconclusive US elections before. They were resolved, but not by any constitutional mechanism and the consequences of such brutal political contests have been severe indeed.

In 2000, the supreme court decided a disputed Florida result and put a Republican, George W Bush, in the White House instead of the Democrat Al Gore. Though of course the justices could not know it, they had put America on the road to war in Iraq, economic crisis, the rise of the evangelical right and a deepening political divide.

That case is well within living memory. But an election much further back produced even more damaging results.

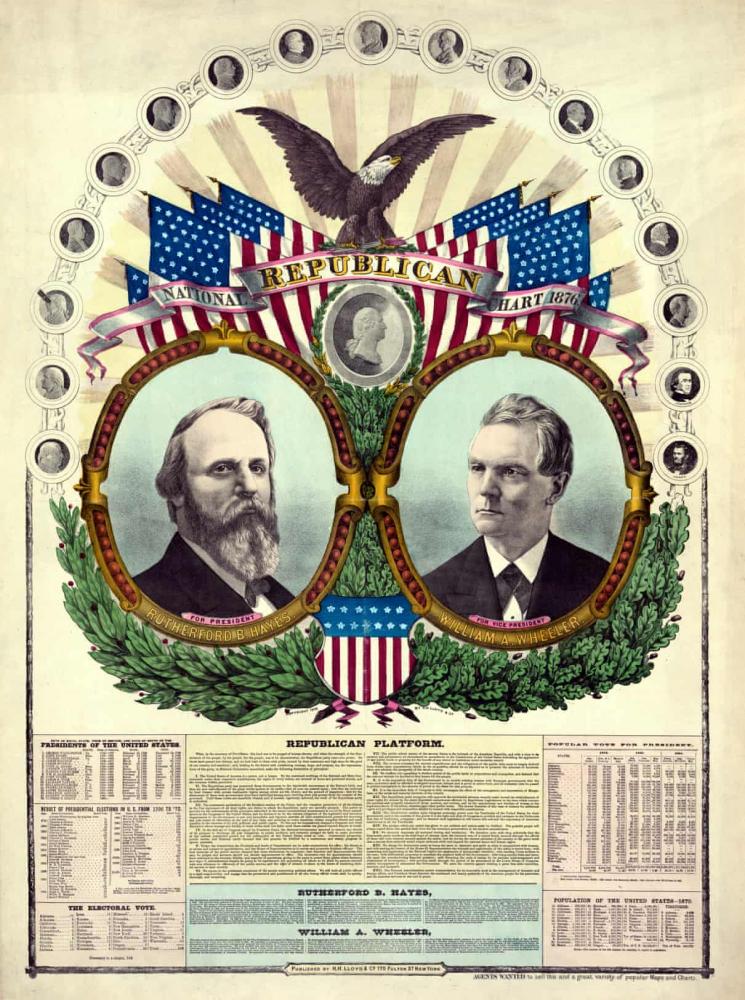

The campaign of 1876 ended with the electoral college in the balance as three states were disputed. Out of deadlock, eventually, came a political deal, giving the Republican Rutherford Hayes the presidency at the expense of Samuel Tilden, who like Gore, and indeed Hillary Clinton in 2016, won the popular vote.

Tilden’s compensation was that his party, the Democrats, were allowed to put an end to Reconstruction, the process by which the victors in the civil war abolished slavery and sought to ensure the rights of black Americans, via the 13th, 14th and 15th constitutional amendments.

The awful result was Jim Crow, the system of white supremacy and segregation which lasted well into the 20th century and whose legacy remains crushingly strong in a country now gripped by protests against police brutality and for systemic reform.

Eric Foner, now retired from Columbia University, is America’s pre-eminent historian of the civil war, slavery and Reconstruction, a prize-winner many times over. He told the Guardian the US of 2020 is not prepared for what may be around the corner.

“In 1877 there were three states, Florida, South Carolina, Louisiana, where two different sets of returns were sent up, one by the Democrats, one by the Republicans, each claiming to have carried the state.

“There was no established mechanism and in fact, in the end, we went around the constitution, or beyond the constitution, or ignored the constitution. It was settled by an extralegal body called the Electoral Commission, which was established by Congress to decide who won.”

National Republican chart from 1876 featuring Rutherford Hayes for president and William Wheeler for vice-president. Photograph: Education Images/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Through wheeling and dealing in smoky back rooms as well as the precincts of Capitol Hill, that process produced a result.

“If there is such a dispute this November,” Foner says, “one of the things that is similar to 1876 is that today you have a divided Congress. Back then, just as now, you had Republicans in control of the Senate and Democrats in control of the House. And that gave each party a lot of power.”

If Trump does refuse to vacate the Oval Office, Biden may have to make concessions.

“Let’s imagine that the Republicans recognize Biden, withdraw their claim that, say, Biden is ahead by 7m popular votes but the electoral college is disputed. In exchange for that, Biden has to promise to do X, Y and Z. He’s got to promise to build the border wall to completion. He’s got to promise to make Russia the 51st state. Whatever it is Trump wants.

“Is that conceivable? I don’t know, probably not. But somebody has to decide and in 1876, in the end, it was this Electoral Commission.

“In 2000, I remember very well, a bunch of historians took a full-page ad in the New York Times, calling for a new Electoral Commission to examine the whole thing, and I thought that was one of the worst ideas I’d ever heard. When you go back to 1876, part of the deal was the surrender of the rights of African Americans. I’m not sure that’s a precedent we want to reinvigorate, you know?”

Many fear Trump and the Republicans will consider no tactic too underhand, no punch too low, before or after the vote.

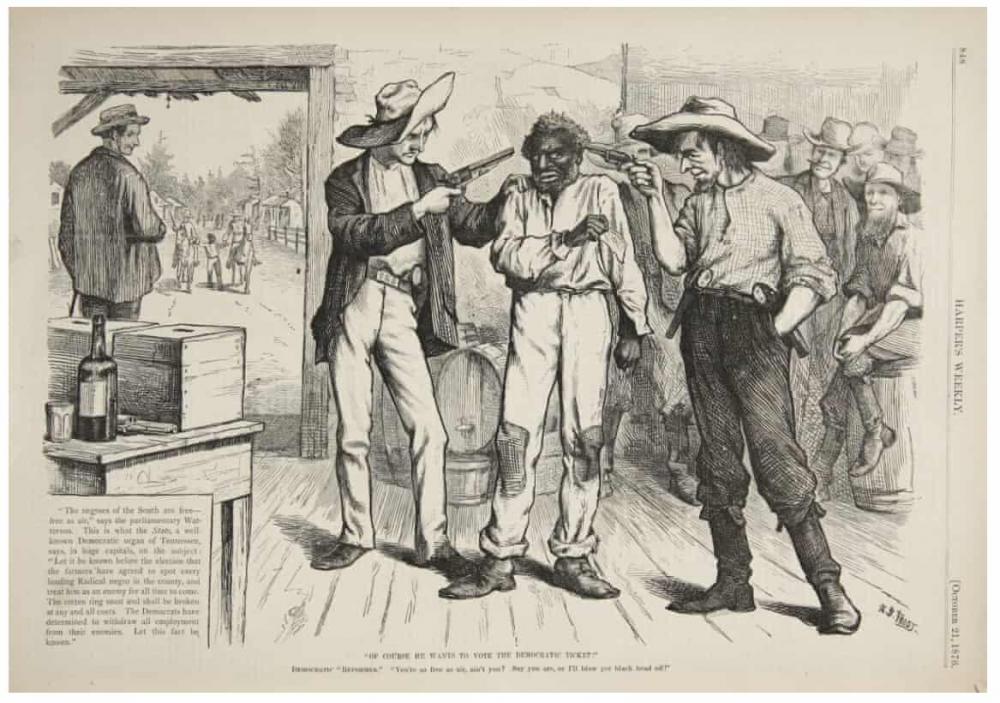

“The election of 1876,” Foner says, “would not have been disputed at all if there hadn’t been massive violence in the south to prevent black people from voting and voter suppression like we have today. Now, voter suppression is mostly legal. Back then it was violent, you know, mob activity or Klan activity or other things to intimidate blacks or prevent them from going to vote.

“In other words if you had a fair election in the south, a peaceful election, there’s no question that the Republican Hayes would have won a totally legitimate and indisputable victory.

“Today, I can certainly see the Trump people challenging these mail-in ballots: ‘They’re all fraudulent, they shouldn’t be counted.’ Challenging people’s voting. There are already efforts to recruit poll watchers to try to intimidate voters, to claim they’re not really registered to vote.”

Many urge that the only real way to resolve fears of a contested result is for the electorate to hand Biden so resounding a victory that Trump will have no choice but to go. Foner agrees, though as “the country is fairly evenly divided, it’s hard to win a landslide election”.

Does he think, as many do, that the US is now as divided as at any time since the civil war and its aftermath?

“Sure, in a sense. We’re in a very ideological moment right now we don’t have the violence. President Grant sent troops into the south in 1871, to suppress the Ku Klux Klan. We had a civil war, which we’re not quite on the verge of yet, I hope.

“But in the aftermath of civil war, yes, the Democrats were explicitly and overtly a party of white supremacy. That was their principle. The Republicans were the party of Lincoln, of emancipation and, increasingly, basic rights for African Americans.

“Those were very different positions and they led to extreme partisanship. Not a single Democrat in Congress voted for any of the so-called Reconstruction legislation which tried to protect the rights of blacks in the south. The hyper-polarization was there, 150 years ago.”

Swap the parties round, and the parallel to today is clear.

A cartoon depicts intimidation techniques used to suppress southern black votes in the election of 1876. Photograph: AB Frost. From Harper's Weekly, October 21, 1876

Foner also says that while a contested result in 2020 could send America down a very dark path, a big Biden victory could herald a brighter future.

“It’s possible Biden wins by a large majority, [the Democrats] get control of the Senate. You know, the atmosphere in the country, whether it’s the racial issue or the pandemic or the economic crisis we’re in, all of that cries out for people who are looking for serious, substantive leadership, which of course we haven’t had lately.

“On the other hand, if Biden squeaks in, you know, with 52% of the vote and the Senate remains in the hands of Mitch McConnell and the Republicans … Biden can reverse all of Trump’s executive orders but he’s not going to get the major progressive legislation through.”

In the words of William Dean Howells, the dean of American 19th-century letters whom Foner has quoted elsewhere, the American public always wants “a tragedy with a happy ending”. Thanks to the election of 1876, Reconstruction did not deliver. As the election of 2020 looms, the Trump presidency may. Or may not.

Martin Pengelly is breaking news and weekend editor for Guardian US.

America is at a crossroads ...

... and its direction in the coming months will define the country for a generation. These are perilous times. Over the last three years, much of what the Guardian holds dear has been threatened – democracy, civility, truth.

The country is at a crossroads. Science is in a battle with conjecture and instinct to determine policy in the middle of a pandemic. At the same time, the US is reckoning with centuries of racial injustice – as the White House stokes division along racial lines. At a time like this, an independent news organisation that fights for truth and holds power to account is not just optional. It is essential.

Like many news organizations, the Guardian has been significantly impacted by the pandemic. We rely to an ever greater extent on our readers, both for the moral force to continue doing journalism at a time like this and for the financial strength to facilitate that reporting.

You’ve read many articles in the last eleven months. We believe every one of us deserves equal access to fact-based news and analysis. We’ve decided to keep Guardian journalism free for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This is made possible thanks to the support we receive from readers across America in all 50 states.

As our business model comes under even greater pressure, we’d love your help so that we can carry on our essential work. If you can, support the Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.