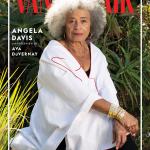

Ava Duvernay Interviews Angela Davis on This Moment - And What Came Before

AVA DuVERNAY: I was reading an interview in which you talked about something that’s been on my mind quite a bit lately. It’s about this time we are in that I’ll just call a racial reckoning. Do you feel that we could have encountered this moment in as robust a manner as we’ve felt it this summer without the COVID crisis having been the foundation? Could one have occurred with this much force without the other?

ANGELA DAVIS: This moment is a conjuncture between the COVID-19 crisis and the increasing awareness of the structural nature of racism. Moments like this do arise. They’re totally unpredictable, and we cannot base our organizing on the idea that we can usher in such a moment. What we can do is take advantage of the moment. When George Floyd was lynched, and we were all witnesses to that—we all watched as this white policeman held his knee on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds—I think that many people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, who had not necessarily understood the way in which history is present in our lives today, who had said, “Well, I never owned slaves, so what does slavery have to do with me?” suddenly began to get it. That there was work that should have happened in the immediate aftermath of slavery that could have prevented us from arriving at this moment. But it did not happen. And here we are. And now we have to begin.

The protests offered people an opportunity to join in this collective demand to bring about deep change, radical change. Defund the police, abolish policing as we know it now. These are the same arguments that we’ve been making for such a long time about the prison system and the whole criminal justice system. It was as if all of these decades of work by so many people, who received no credit at all, came to fruition.

You understood the dangers of American policing, the criminalization of Black, native, and brown people, 50 years ago. Your activism and your scholarship has always been inclusive of class and race and gender and sexuality. It seems we’re at a critical mass where a majority of people are finally able to hear and to understand the concepts that you’ve been talking about for decades. Is that satisfying or exhausting after all this time?

I don’t think about it as an experience that I’m having as an individual. I think about it as a collective experience, because I would not have made those arguments or engaged in those kinds of activisms if there were not other people doing it. One of the things that some of us said over and over again is that we’re doing this work. Don’t expect to receive public credit for it. It’s not to be acknowledged that we do this work. We do this work because we want to change the world. If we don’t do the work continuously and passionately, even as it appears as if no one is listening, if we don’t help to create the conditions of possibility for change, then a moment like this will arrive and we can do nothing about it. As Bobby Seale said, we will not be able to “seize the time.” This is a perfect example of our being able to seize this moment and turn it into something that’s radical and transformative.

I love that. I know that there’s a lot of energy around how to keep the attention. But what you’re saying is it needs to be happening in isolation of any outside forces. So that when the right time comes, there’s a preparation that had already been in process. Don’t think so much about sustaining the moment. Just always be prepared for the moment when it comes, because it will.

Exactly. I’m also thinking about your contributions. So many people have seen your work, your films: 13th and the film on the Central Park Five.

When They See Us! I can’t believe you know about it. I’m excited.

Oh, my God. I’ve not only seen it, but I’ve encouraged other people to look at it. I saw that really moving conversation between the actors and the actual figures. All of that helps to create fertile ground. I don’t think that we would be where we are today without your work and the work of other artists. In my mind, it’s art that can begin to make us feel what we don’t necessarily yet understand.

You’ve just made my life saying that. Thank you is not enough. There is a lot of talk about the symbols of slavery, of colonialism. Statues being taken down, bridges being renamed, buildings being renamed. Does it feel like performance, or do you think that there’s substance to these actions?

I don’t think there’s a simple answer. It is important to point to the material manifestations of the history that we are grappling with now. And those statues are our reminders that the history of the United States of America is a history of racism. So it’s natural that people would try to bring down those symbols.

If it’s true that names are being changed, statues are being removed, it should also be true that the institutions are looking inward and figuring out how to radically transform themselves. That’s the real work. Sometimes we assume the most important work is the dramatic work—the street demonstrations. I like the term that John Berger used: Demonstrations are “rehearsals for revolution.” When we come together with so many people, we become aware of our capacity to bring about change. But it’s rare that the actual demonstration itself brings about the change. We have to work in other ways.

I always love talking to you because you drop nine references in the conversation. You give me a reading list after from your citations. John Berger. Writing that down. One of the things that you’ve talked about that I hold on to is about diversity and inclusion. In many industries, especially the entertainment industry where I work, those are buzzwords. But I see them in the way that you taught me during our conversation for 13th. These are reform tactics, not change tactics. The diversity and inclusion office of the studio, of the university, of whatever organization, is not the quick fix.

Absolutely. Virtually every institution seized upon that term, “diversity.” And I always ask, “Well, where is justice here?” Are you simply going to ask those who have been marginalized or subjugated to come inside of the institution and participate in the same process that led precisely to their marginalization? Diversity and inclusion without substantive change, without radical change, accomplishes nothing.

“Justice” is the key word. How do we begin to transform the institutions themselves? How do we change this society? We don’t want to be participants in the exploitation of capitalism. We don’t want to be participants in the marginalization of immigrants. And so there has to be a way to think about the connection among all of these issues and how we can begin to imagine a very different kind of society. That is what “defund the police” means. That is what “abolish the police” means.

How can we apply that to the educational system?

Capitalism has to be a part of the conversation: global capitalism. And it’s part of the conversation about education, because what we’ve witnessed is increasing privatization, and the emergence of a kind of hybrid: the charter schools. Privatization is why the hospitals were so unprepared [for COVID-19], because they function in accordance with the dictates of capital. They don’t want to have extra beds because then that means that they aren’t generating the profit. And why is it that they’re asking children to go back to school? It’s because of the economy. We’re in a depression now, so they’re willing to sacrifice the lives of so many people in order to keep global capitalism functioning.

I know that’s a macro issue, but I think we cannot truly understand what is happening in the family where the parents are essential workers and are compelled to go to work and have no childcare. Not only should there be free education, but there should be free childcare and there should be free health care as well. All of these issues are coming to a head. This is, as you said, a racial reckoning. A reexamination of the role that racism has played in the creation of the United States of America. But I think we have to talk about capitalism. Capitalism has always been racial capitalism. Wherever we see capitalism, we see the influence and the exploitation of racism.

We haven’t been talking a lot about that period of Occupy. I think that when we look at how social movements develop, Occupy gave us new vocabularies. We began to talk about the 1 percent and the 99 percent. And I think that has something to do with the protests today. We should be very explicit about the fact that global capitalism is in large part responsible for mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex, as it is responsible for the migrations that are happening around the world. Immigrants are forced to leave their homelands because the system of global capitalism has made it impossible to live human lives. That is why they come to the U.S., that is why they come to Europe, seeking better lives.

How does it feel for a woman born into segregation to see this moment? What lessons have you gleaned about struggle?

That’s a really big question. Perhaps I can answer it by saying that we have to have a kind of optimism. One way or another I’ve been involved in movements from the time I was very, very young, and I can remember that my mother never failed to emphasize that as bad as things were in our segregated world, change was possible. That the world would change. I learned how to live under those circumstances while also inhabiting an imagined world, recognizing that one day things would be different. I’m really fortunate that my mother was an activist who had experience in movements against racism, the movement to defend, for example, the Scottsboro Nine.

I’ve always recognized my own role as an activist as helping to create conditions of possibility for change. And that means to expand and deepen public consciousness of the nature of racism, of heteropatriarchy, pollution of the planet, and their relationship to global capitalism. This is the work that I’ve always done, and I’ve always known that it would make a difference. Not my work as an individual, but my work with communities who have struggled. I believe that this is how the world changes. It always changes as a result of the pressure that masses of people, ordinary people, exert on the existing state of affairs. I feel very fortunate that I am still alive today to witness this.

And I’m so glad that someone like John Lewis was able to experience this and see this before he passed away, because oftentimes we don’t get to actually witness the fruits of our labor. They may materialize, but it may be 50 years later, it may be 100 years later. But I’ve always emphasized that we have to do the work as if change were possible and as if this change were to happen sooner rather than later. It may not; we may not get to witness it. But if we don’t do the work, no one will ever witness it.