Diane di Prima: A Tribute

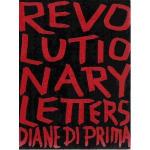

Revolutionary Letters

Pocket Poets Series No. 27

Diane di Prima

City Lights Books

ISBN-13 9780872867611

It might have pleased Diane di Prima that we can’t get our hands on her “Revolutionary Letters” by capitulating to the rapacity of Amazon Prime. The book is out of print. Instead, after her death, individual poems from her lifelong series pop up on my social media feeds, between presidential tweets and images of police violence. This is not unlike how the poems first circulated in the late ’60s and early ’70s with the Liberation News Service, as one-offs in free papers. Di Prima always loved Ezra Pound’s formulation — “all ages are contemporaneous” — and lately her poems have seemed perfectly present tense: The “Revolutionary Letters” warn against “the tale, so often told” in times of crisis, “that now we must organize, obey the rules, so that later/we can be free.”

Di Prima wasn’t one to wait for history to authorize the freedoms she desired. She came of age before the women’s movement, in a middle-class Italian family governed by traditional gender roles. She escaped Brooklyn for Hunter, the magnet high school for gifted kids in Manhattan, where she fell in with a crowd — “maverick and mostly gay” — that included Audre Lorde. In 1953, when she was 18, she moved to East Fifth Street to write, taking odd jobs to pay the bills.

Di Prima is best remembered as a Beat poet, one of few women in a scene associated with the headlong, half-mad incantations of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs — a bohemian rebellion in lifestyle and syntax more than a decade before hippies made counterculture mainstream. Di Prima’s detailed life writing (“Memoirs of a Beatnik,” from 1969, and “Recollections of My Life As a Woman,” from 2001) describe how she found a place for herself in the downtown labyrinth of jazz clubs and dyke bars, happenings and protests.

Di Prima entered what had mostly been a conversation among men through sheer audacity, when she sent her first book — “This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards” — to the poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who wrote the introduction and whose indie press, City Lights, had recently issued Ginsberg’s world-piercing “Howl.” Di Prima recalls in “Recollections” that she was not often invited to read alongside her peers, despite her central role in that community as poet, theater director and editor. In 1961, she started a mail-order mimeograph with Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones), and for two and a half years they were lovers. The editorial vision was truly collaborative, but she remembers that she was always the one left with the manual labor of cutting and pasting.

These inequalities seemed like “a matter of course” to di Prima, so she worked around them. When she was 22, she had a child out of wedlock. “To my mind, ‘father’ was a mythic, insubstantial relationship” that did little to inspire responsible behavior in the men she had known. Therefore, she wrote in “Recollections,” “the child I bore” — Jeanne di Prima — would be mine and mine alone.”

It’s tempting to see di Prima as an extraordinary exception to the midcentury rule, but she carefully reminded us that there have always been exceptions: She was especially drawn to “the women blues singers: Sara Martin, Trixie Smith,” who often had to “mother, disappear, get sick” in the windy breaks between verses, quotidian struggles they would weave back into the music. She learned to write “modular poems, that could be dropped and picked up” between literary commitments and child care. When called upon to articulate an aesthetic statement, di Prima wrote: “The requirements of our life is the form of art.”

Even traumatic episodes were opportunities for creative discovery: Baraka wanted her to have an abortion the first time they conceived — he was still married to Hettie Jones. She reluctantly agreed, ultimately deciding she “had to experience being the betrayer” of her own impulse to sustain the pregnancy. She thought of the abortion as a bitter but necessary experiment, a way “to continue to write” into uncharted psychic territory. Framing the choice as artistic helped her alchemize the lonely bus ride to an underground clinic in mining country, and the life-changing grief that came after. But one experiment was enough. The next time she conceived with Baraka, she would give birth to her second daughter, Dominique.

Misogyny continued to structure her life among artists, but she behaved as though mutual aid, free love and poetry itself would pave her way forward. Remarkably often, that’s what happened. She moved to California in 1968, where she stayed for the rest of her life, establishing a crucial link between the New York avant-garde and San Francisco’s emergent counterculture. For a while, she kept a “Free Bank” on the top of her refrigerator — just “a shoe box full of money” for anyone who needed it.

In “Revolutionary Letter #46,” she warned the skeptics: “As you learn the magic, learn to believe it/Don’t be ‘surprised’ when it works.” But di Prima’s faith in the power of poetry to produce solidarity and social change was also a kind of performance — not false at all, but a way of rehearsing, repeatedly, for the world she wished to live in.

Carina del Valle Schorske is a writer and translator living between San Juan, P.R., and New York City. Her first book, “The Other Island,” is forthcoming from Riverhead.

(Moderator's note: A new edition of Revolutionary Letters is forthcoming from City Lights Books. Information can be found at the publisher's website: http://www.citylights.com/book/?GCOI=872861004460200.)