Whitewashing the Great Depression

Quick, name one iconic Depression-era portrait each by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Russell Lee. My guess is that you’d choose Lange’s Migrant Mother, a portrait of Florence Owens Thompson and her children taken in Nipomo, California, in 1936. For Evans, you’d probably pick a 1936 portrait of tight-lipped Allie Mae Burroughs standing before the wall of her family’s cabin in Hale County, Alabama. For Lee, you might draw a blank, but you’d likely recognize his 1937 group portrait Saturday Night in a Saloon, showing four drinkers in Craigville, Minnesota. (It was used in the opening sequence of the TV show Cheers.)

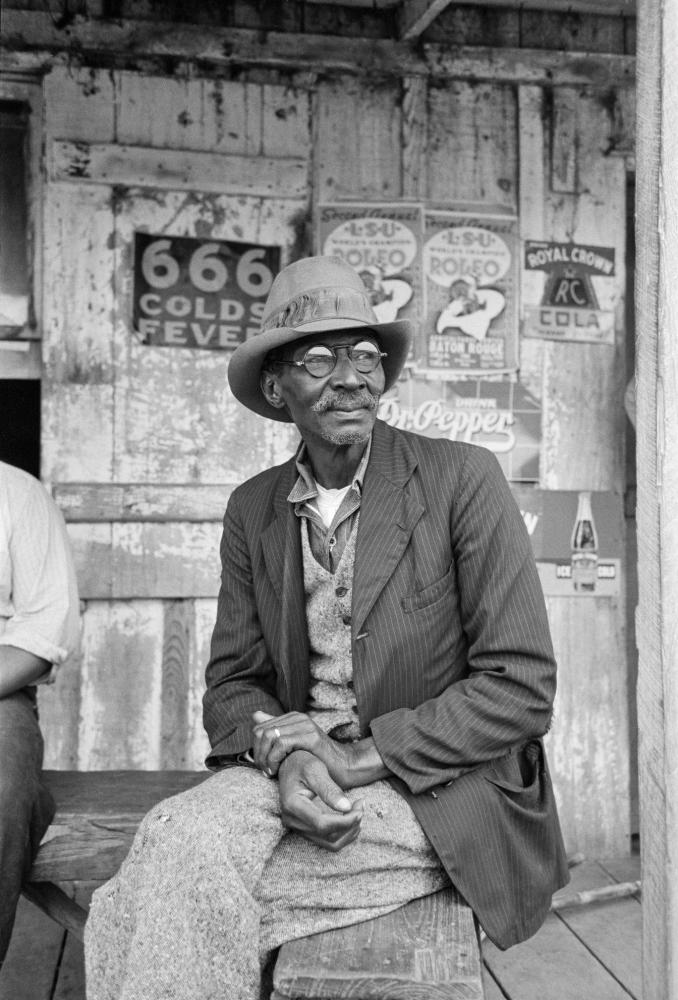

What’s my point? Each of the subjects in each of these pictures, produced by Farm Security Administration photographers, appears to be white. Although the photographers who worked for the FSA took many pictures of people of color—in the streets, in the fields, out of work—the Great Depression’s main victims, as Americans came to visualize them, were white. And this collective portrait has contributed to the misbegotten idea, still current, that the soul of America, the real American type, is rural and white.

In one sense, the lack of diversity in classic FSA photographs comes as little surprise: The country was roughly 90 percent white during the Depression, and the FSA represented Black people in proportion to their share of the population. Yet overall representation is surely only part of the story, given that the FSA was supposed to be chronicling hardship among farmworkers. During the Depression, Black Americans made up more than half of the country’s tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and farmworkers in the South. In 1932, when a quarter of white Americans were unemployed, half of Black Americans were. “In some Northern cities, whites called for African Americans to be fired from any jobs as long as there were whites out of work,” according to the Library of Congress’s website for teachers. And Black sharecroppers were often forced out of work by white ones. “No group was harder hit than African Americans.”

Yet we’ve come to imagine the Great Depression as largely a white tragedy. That isn’t because the FSA photographers focused only on white subjects. If you look at the roughly 175,000 negatives in the complete FSA/Office of War Information file, now at the Library of Congress, you’ll see that the photographers working for the FSA and for its predecessor, the Resettlement Administration, and its successor, the OWI, documented many people of color. Lee photographed poor Black people in Missouri, and Mexican pecan shellers in Texas. Evans photographed Black Americans out of work in Mississippi and Alabama. And Lange photographed Filipino lettuce pickers and Japanese truck farmers in California.

The most direct responsibility for the whitewashing seems to lie with the photographers’ boss, Roy Stryker, who was the chief of the FSA’s historical section from 1935 to 1941, and then of the OWI’s photography unit. Three new books that pursue three very different subjects in very distinctive ways—Walker Evans: Starting From Scratch, by Svetlana Alpers; Russell Lee: A Photographer’s Life and Legacy, by Mary Jane Appel; and Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, a Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog—all offer evidence that FSA photographers often tangled with Stryker over matters of race.

Stryker openly worried that too much racial honesty might sink his ship at the FSA. Part of his mission at the agency was to compile a complete pictorial record of all kinds of Americans, known as “The File.” The other part was to present to Congress a sympathetic portrayal of American suffering, “to document the problems of the Depression,” as one photographer recalled, “so that we could justify the New Deal legislation that was designed to alleviate them.”

Library of Congress

Stryker, in other words, was a realist. And the reality was that Congress, which controlled the FSA’s funds, was dominated by Southern Democrats, who, as Appel writes in her Lee biography, were “interested in preserving the racial status quo.” Knowing this, Stryker and other FSA officials “were reluctant to lead the agency in a crusade against racial disparity.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself feared the Southern Democrats. Without their support, his New Deal programs had no hope of surviving. Thus, although FDR signed an order barring discrimination in the projects sponsored by his newly founded Works Progress Administration in 1935, Appel notes that he wouldn’t back “an anti-lynching campaign because he was afraid of losing his Southern Democratic base.” And when the Social Security Act was passed, also in 1935, agricultural and domestic workers (who were disproportionately Black) were excluded from its benefits.

To tug at the Dixiecrats’ heartstrings, Stryker realized that the photographs presented to them had to accentuate white suffering. Even local FSA bureaucrats “resisted the inclusion of black farmers in their public relations material,” Appel writes. One FSA official in Amarillo, Texas, who claimed he was “sincerely sympathetic to all races, including Negroes,” asked about a local exhibit organized by the FSA photographer Edwin Rosskam in the late 1930s: “Why was it necessary for Mr. Rosskam to use a picture of a Negro farmer on the fourth panel? Surely he had photos of German farmers, Russian farmers, Italian farmers, Irish farmers, etc.”

Stryker controlled the imagery in different ways. He punched holes in negatives he didn’t want to use. He also carefully steered his photographers in the field. (Their ranks included Jack Delano, Louise Rosskam, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, and Marion Post Wolcott.) As Sarah Hermanson Meister, the curator of the recent MoMA exhibit of Lange’s work, writes: “One of Roy Stryker’s strategies … was to give them what he called ‘shooting scripts’ … lists of keywords, organized by topic, which he hoped would shape their vision and draw their attention to particular signs of the times.” For instance, the script he wrote to promote the need for the Farm Debt Adjustment program requested shots of a courtroom scene, a sheriff, a farmer dumping milk. The results, not altogether surprisingly, were white as milk.

To varying degrees, the photographers followed Stryker’s direction. In an interview in the 1960s, Stryker said he’d had a stable of photographers “I could trust implicitly.” But there were tensions. In 1936, for example, Stryker sent Evans to Mississippi to document soil erosion and “the present state of buildings.” Evans duly recorded erosion, shacks, wrecked plantation houses, and storefronts. But he also went further, taking many photos of people in the Black quarters of Vicksburg and Tupelo. He didn’t seem to care that the government hadn’t asked for such pictures. In 1937, Evans was fired by Stryker, who pinpointed the reason for his irritation with Evans a quarter century later: “Walker wasn’t going to cooperate … I had to have people who would not only take the pictures they wanted.”

Library of Congress

The FSA leaders weren’t alone in skewing the portrait of the Depression’s victims. Magazine publishers did their part, too. In 1936, Evans traveled with James Agee to document the houses of three sharecropper families in Hale County for Fortune magazine. As Agee noted later, the magazine requested “a photographic and verbal record of the daily living and environment of an average white family of tenant farmers.” Evans flouted the order, documenting both Black and white farmers. However, when he and Agee put together Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), which included pictures from that trip, they notably left out the pictures of Black Americans. These were added only in 1960, in a second edition. Alpers writes that Evans put in “a final section of photographs … a main street, a plantation house, black men on a sidewalk.”

Lange also chafed at the racial limits. As Robert Slifkin notes in the MoMA catalog, FSA leadership instructed her to “focus attention on the plight of white victims” and to “avoid representing instances of interracial sociality.” She didn’t always comply. Take Plantation Overseer and His Field Hands, Mississippi Delta (1936), a widely circulated group portrait featuring Black farmhands looking plaintively at the camera next to a plump white overseer. When this picture appeared in the U.S. Camera Annual in 1939, it carried an incendiary caption, a quote from a viewer outraged at the racial oppression depicted: “Did or didn’t you know slavery was abolished?”

Like Lange and Evans, Lee bridled under the selective hand of Stryker. On a 1938 visit to dozens of homes in a New Deal planned community called the Southeast Missouri Farms Project, Lee, tasked with showing the successes of the program, focused on the continuing hardships there instead. His work emphasized a group of “primitive shanties” with no electricity. The occupants there were both Black and white, and his goal, Appel points out, was to “suggest comparable levels of poverty.” In two separate houses, for instance, Lee took two portraits, one of a white boy combing his hair before a mirror and one of a Black girl doing the same. Appel observes:

Newspapers—provisional insulation or makeshift wallpaper—cover the walls. Both bureaus are cluttered and, in homes without electricity, oil lamps sit near the mirrors. As they comb their hair, both children stand barefoot on dirty wooden floors.

Although these two photographs are similar and are now filed together at the Library of Congress, they had very different fates. Son of a Sharecropper, the picture of the white boy, ran in many newspapers. Sharecropper’s Child, featuring the young Black girl, was rarely seen, and Appel has found no evidence that it was ever published.

Lee’s biggest rift with Stryker came in 1939, over his photographs of Mexican pecan shellers in San Antonio. By this time, the Depression was lifting and the pressures on Stryker had shifted. He needed to show Congress the results of the aid it had given to farmers—upbeat shots. But Lee kept photographing unemployed workers (mostly Mexican) and their kids waiting in food lines. He also documented the food they got every two weeks for their families—“a small sack of beans and a block of butter.” In response to these dismal shots, Stryker asked Lee to “start a series of pictures showing the operation and life on somewhat better farms,” which Stryker himself called “glorification pictures.” Lee did so, but remained focused on the downtrodden. This irritated Stryker: “I must say that I can’t do much glorifying out of anything you’ve taken.”

Library of Congress

As the depression came to an end, a wide array of FSA photographs became public. In April 1938, a large show of FSA pictures was part of New York City’s “First International Photographic Exposition” at Grand Central Palace, and those photos were then picked up by the Museum of Modern Art for a national tour. Later that same year, MoMA gave Evans a solo show, “American Photographs.” (This was MoMA’s first-ever one-person photography exhibition.) In 1939, Lange published An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, a title that seems to poke fun at Stryker’s giving preference to soil erosion. And then, in 1941, came 12 Million Black Voices, written by the novelist Richard Wright and compiled by Edwin Rosskam. This book, which included photographs by Evans, Lange, and Lee, flew in the face of the American mythology that the FSA had been constructing.

Interestingly, Stryker gave the book his full support. Perhaps he was freer to do so with the economy on the mend. But clearly he remained conflicted about how to handle the race question. In 1942, upon meeting the Black photographer Gordon Parks, who had just won an FSA fellowship, Stryker sent him without his camera to see the sights in Washington, D.C., knowing full well he’d get a good dose of the city’s segregated ways. When Parks returned, having been barred from all-white lunch counters and movie theaters, Stryker encouraged him to go back out with his camera, to “put a face on racism,” starting with the FSA offices. In a now famous portrait, American Gothic, Washington, D.C., Parks immortalized a cleaning woman at the FSA, Ella Watson, holding a mop and a broom in front of the American flag. Stryker’s reaction captured his sense of caution as well as his sympathy: “My God, this can’t be published, but it’s a start.”

During World War II, many of Stryker’s FSA photographers started taking pictures at the Office of War Information, whose mission was connecting American civilians to the war effort through radio broadcasts, newspapers, photographs, and films. When, in 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, commanding the internment of anyone of Japanese descent, Lange was hired by the government’s War Relocation Authority to document how the policy was being executed. “American nationalism became explicitly racialized,” Linda Gordon writes in Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. White Americans were taught to identify and turn in the Japanese, whose faces were presumed to signify “disloyalty and treachery.”

In Focus: Photos of the World War II internment of Japanese Americans

Lange, who was vehemently opposed to the relocation program, made some 800 heartrending photographs of Japanese American families as they packed up their farms, businesses, and houses and were loaded onto buses and trains, tagged with numbers, and imprisoned in barracks. (She was to take “no pictures of the barbed wire or watchtowers or armed soldiers.”) Clearly sympathetic to the victims of internment, Lange’s photographs remained out of public view. As Gordon writes, “she was required to turn over all negatives, prints, and undeveloped film from this work—then her pictures were impounded for the duration of the war.” By the time these photos became public (you can now see Lange’s personal archive online at the Oakland Museum of California), the war was over. As Lange later remarked: “They had wanted a record, but not a public record.”

In the end, though, censoring, withholding, scripting, and editing what the cameras capture can control only so much. Photographs, even those shot with a specific purpose, have a way of yielding surprises long after they are taken.

Consider Migrant Mother. On the day Lange took the picture, in March 1936, she was in the rain-sogged pea-pickers’ camp for only 10 minutes. And she was uncharacteristically sloppy: She didn’t get the name or history of the woman she photographed in a tent with her kids, and her caption went on to describe a mother so desperate for food for her family that she’d sold the tires off her car. The effect was powerful: Shortly after the photo ran in The San Francisco News, the U.S. government sent 20,000 pounds of food to the campsite in Nipomo. But by the time it arrived, the Migrant Mother and her kids were gone.

Four decades later, Florence Owens Thompson surfaced to tell her real story. She hadn’t sold her tires to buy food, as Lange reported. She and her kids didn’t live in Nipomo; they had stopped there briefly because their car had broken down. Once the car was fixed, she and her family had moved on (the car had tires). Plus, she wasn’t white, as everyone had assumed. She was Cherokee, a nonwhite citizen. But no matter. Her work for the American image was already done.

[SARAH BOXER, a critic and cartoonist, is the author of two psychoanalytic comics, In the Floyd Archives and Mother May I?, and one Shakespearean tragi-comic, Hamlet: Prince of Pigs.]