The ‘Blood Drawn by the Lash’ and the Crimes of This Guilty Land

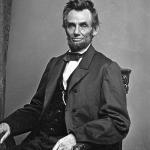

Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times

by David S. Reynolds.

Penguin, 1066 pp., £33.69, September, 978 1 59420 604 7

The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle for American Freedom

by H.W. Brands.

Doubleday, 445 pp., £24, October, 978 0 385 54400 9

Abraham Lincoln , memorialized as a child of the frontier, self-made man and liberator of the slaves, has been the subject of more than 16,000 books, according to David S. Reynolds’s new biography, Abe. That’s around two a week, on average, since the end of the American Civil War. Almost every possible Lincoln can be found in the historical literature, including the moralist who hated slavery, the pragmatic politician driven solely by ambition, the tyrant who ran roughshod over the Constitution, and the indecisive leader buffeted by events he could not control. Conservatives, communists, Civil Rights activists and segregationists have claimed him as their own. Esquire magazine once ran a list of ‘rules every man should know’. Rule 115: ‘There is nothing that can be marketed that cannot be marketed better using the likeness of Honest Abe Lincoln.’

It seems safe to assume that even the most diligent researcher will not be able to discover significant new material about Lincoln – a diary, say, or previously unknown speeches and letters. Instead the biographer must take an original interpretative approach. And, against all odds, Reynolds, who teaches at the City University of New York, manages to say new and important things about Lincoln in his elegantly written book. Rather than a conventional account of Lincoln’s life, Abe is a ‘cultural biography’. The familiar trajectory of Lincoln’s career is here, from his youth in Kentucky and Indiana to his emergence as a national figure forced to preside over a cataclysmic war and its ‘astounding’ (Lincoln’s word) result: the emancipation of four million slaves. But Reynolds is more interested in the way Lincoln’s character and political outlook reflected ‘the roiling cultural currents’ of the nation in which he lived.

Lincoln’s America, Reynolds says, was suffused with sensationalism, violence, raw humor, and spectacles high and low. On the streets of New York, theatregoers attending performances of Shakespeare rubbed shoulders with the audiences for blackface minstrel shows.

Nearby, P.T. Barnum’s American Museum featured General Tom Thumb (an adult less than three feet tall) alongside such frauds as the ‘Feejee Mermaid’. Lincoln felt at home with both elite and popular culture. Reynolds believes that his success as a politician stemmed from his engagement with the diverse cultural phenomena around him. For Reynolds, Lincoln really was ‘Abe’, the everyman depicted in his campaign literature.

To situate Lincoln in his cultural context, Reynolds takes the reader down numerous narrative byways. A discussion of Lincoln’s taste in music, including the erotic ballad ‘I won’t be a nun’ and, improbably, ‘Dixie’, a paean to the Old South, leads to a long examination of 19th-century popular song. When, after the death of their 11-year-old son Willie, Lincoln and his wife Mary arrange for seances in the White House, we learn about the popularity of spiritualism. Mention of Uncle Tom’s Cabin leads to a discussion of the emotional intensity of mid-century writing and what Reynolds calls the ‘opportunistic sensationalism’ of reformers who dwelled on the degradation of drinkers and the physical abuse of slaves, an approach Lincoln rejected as counter-productive.

The relevance of these excursions is sometimes open to question. Political cartoonists sometimes depicted Lincoln in the guise of Charles Blondin, a tightrope walker famous for crossing Niagara Falls on a high wire, navigating a dangerous course without leaning too far to the left or right. Reynolds describes Lincoln as a ‘political Blondin’, who chose an ideologically balanced ‘Blondin-like’ Cabinet and sought a ‘Blondin-like balance in the military’ by appointing both Democrats and Republicans to command troops. The repeated invocation of Blondin is certainly original, and Lincoln did mention him in an 1862 meeting with an abolitionist delegation, but Reynolds’s claim that Lincoln ‘identified strongly’ with the celebrated daredevil is a bit of a stretch.

Reynolds’s Lincoln is not simply a sponge who absorbs what’s going on around him in the culture. Abe devotes far more attention than most biographies to Lincoln’s formative years on the frontier, where he learned to trust his own judgment. Unlike most frontiersmen, he did not hunt, gamble, drink or use tobacco. At a time of intense religious revivalism, Lincoln never joined a church and even expressed admiration for Tom Paine’s Deist tract The Age of Reason. Lincoln didn’t share the prevailing hatred of Native Americans and despite his physical presence (he was 6’4”) tried to avoid the brutal altercations that marked the region’s rough-and-tumble male culture. At an early point in his career Lincoln even suggested that property-owning women should enjoy the right to vote. Despite Reynolds’s subtitle, ‘Abraham Lincoln in His Times’, the Lincoln of Abe sometimes seems like a woke inhabitant of our own era: ‘environmentally conscious’, forward-looking with regard to gender, kind to animals and sympathetic towards ‘ethnic others’.

Reynolds sees 19th-century America as a country that lacked coherence, where individualism was rampant and established institutions weak. The resulting ‘formlessness’, he argues, gave Lincoln a desire for structure in both his own life and the larger world. As a counterweight to the centrifugal forces around him, he revered the national Union, represented by the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, documents that his speeches brilliantly enlisted in the cause of anti-slavery. As a party leader in Illinois, Lincoln understood the need to maintain peace among the various Republican factions – radicals and conservatives, nativists and immigrants, former Democrats and former Whigs. Union was as essential to the party as to the nation. In his personal life, Lincoln sought to enlist reason against his tendency towards intense emotion and occasional depression.

Politically, Reynolds writes, Lincoln ‘stuck close to the centre’, seeking a middle ground between abolitionists, whose intemperate attacks on individual slaveowners seemed to him to endanger the Union, and Northerners indifferent to the evil of the South’s ‘peculiar institution’. Because of his reverence for the Union, Lincoln called for Northern acquiescence in measures he privately abhorred, notably the draconian Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, since the Constitution established the right of owners to have runaways captured and returned. His idol was Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, known as the Great Compromiser. Clay died in 1852, and Lincoln must have realized that his fifty-year effort to rid his state of slavery had accomplished nothing. But well into the Civil War, Lincoln clung to Clay’s plan for abolition: gradual emancipation, monetary compensation to the owners, and ‘colonization’ – that is, encouraging freed slaves to leave the United States for Africa or the Caribbean.

What does all this tell us about what Reynolds calls the ‘hotly contested’ subject of Lincoln’s racial attitudes? A little over twenty years ago, Lerone Bennett Jr, an African American historian, published Forced into Glory, which drew on Lincoln’s prewar statements opposing civil and political rights for Blacks (his comment on female suffrage was limited to whites), and his advocacy of colonizing freed slaves, to depict him as an inveterate racist. The book had the drawbacks of any prosecutor’s brief, but it forced historians and the general public to confront aspects of Lincoln’s career that had mostly been swept under the rug. Outraged members of what one scholar has called the ‘Lincoln-Industrial Complex’ rushed to defend the Great Emancipator.

Insisting on ‘the complete falsity of the charges of innate racism’, Reynolds joins the defence. He insists that in interactions with individual African Americans, Lincoln did not display signs of prejudice. To mitigate the fact that Lincoln, like many of his white contemporaries, enjoyed blackface minstrel shows, Reynolds advances the not entirely convincing argument that these racist performances communicated a ‘cloaked progressiveness’, because their white performers made up as Blacks sometimes assumed, for comic effect, positions of power. Reynolds makes clear that no one with political ambitions could ignore the deeply ingrained racism of Illinois. The state’s notorious Black Laws denied Blacks basic rights, and racist language suffused politics. In the 1858 debates during the campaign for one of Illinois’s seats in the Senate, Lincoln’s antagonist, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, freely used the word ‘nigger’ and accused Lincoln and the ‘Black Republicans’ of wanting freed slaves to move to Illinois, take the jobs of whites, and marry white women. Warned that Douglas’s assault was weakening his party’s electoral chances, Lincoln denied that he believed in ‘Negro equality’. But unlike Douglas, Reynolds points out, he did not waver from the conviction that the inalienable rights in the Declaration of Independence – life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – applied to all persons, regardless of race. These are valid points. Nonetheless, it is fair to say that unlike the abolitionists, who demanded not only an immediate end to slavery but full citizenship rights for Blacks, Lincoln found it impossible to imagine the United States as a biracial society of equals.

A writer who chooses his words with care, Reynolds struggles to find the right ones for Lincoln’s racial views. At one point he refers to his subject’s ‘hidebound’ outlook. He writes that Lincoln ‘associated himself’ with colonization, a weak way of describing his service on the Board of Managers of the Illinois Colonisation Society and his numerous speeches and presidential messages promoting the policy. At a notorious 1862 meeting with a group of free African Americans, Lincoln urged his listeners to encourage emigration among their people. Reynolds sees this encounter, which outraged most Black leaders and seems to have inspired racial violence in the North, as a calculated performance to prepare conservative whites for the coming announcement of emancipation.

Once he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January, 1863, Lincoln’s racial views underwent rapid evolution. Unfortunately, while devoting a chapter to a careful analysis of Lincoln’s two greatest speeches, the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, Reynolds says relatively little about the Proclamation, although that pivotal document offers compelling evidence of the changes in Lincoln’s thinking. In it, Lincoln abandoned his long-held plan for gradual emancipation in favor of immediate freedom for more than three million slaves (about 750,000 were not covered, mostly because they lived in states that had not seceded) and dropped the idea of colonization, urging Blacks to ‘go to work for reasonable wages’ in the United States. For the first time, he authorized the enrollment of African Americans in the Union army. Lincoln doubtless understood that military service would lead to demands for equal citizenship after the war. He never became egalitarian in a modern sense, but in the last two years of his life, spurred by the crucial role of Black soldiers in the ongoing conflict, his thinking changed dramatically. In his final speech, in 1865, he publicly advocated the right to vote for educated Blacks and those who had served in the army. By then he had moved well beyond his culture: at the time only a tiny number of Black men enjoyed the right to vote.

In The Zealot and the Emancipator, H.W. Brands has written a dual biography of Lincoln and the abolitionist John Brown, who in 1859 led a band of 22 men to seize the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in the hope of sparking a slave insurrection. The divergent paths chosen by Brown and Lincoln illuminate a problem as old as civilization itself – what is a person’s moral responsibility in the face of glaring injustice?

Lincoln and Brown never met. Both came from humble origins, but in many ways they could not have been more different. Lincoln thrived in the world of 19th-century American capitalism, rising through ambition, hard work and continual self-improvement to solid middle-class status, while Brown, who failed at numerous ventures and more than once experienced bankruptcy, seemed to sink beneath the economy’s turbulent waters. Where Lincoln the rationalist declared that man could not know the will of God, Brown ‘knew’ that he had been chosen for a divine mission to overthrow slavery. Lincoln condemned mob violence and insisted that respect for the rule of law must become the nation’s ‘political religion’. Brown, like many abolitionists, believed in a ‘higher law’ that legitimized resistance to unjust man-made statutes.

As with Lincoln, the historical literature contains many John Browns – freedom fighter, terrorist, Civil Rights pioneer and madman. For an earlier generation of historians, who saw the Civil War as needless carnage brought on by irresponsible fanatics, Brown was Exhibit A. But African American radicals have long hailed Brown as a rare white person willing to sacrifice himself for the cause of racial justice. Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the idea of ‘Black Power’ in the 1960s, identified Brown and the Radical Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens as the only white figures in American history worthy of admiration. Lately, with the destruction of slavery occupying a central place in accounts of the era’s history, Brown has come to be widely admired. Fifteen years ago, Reynolds published an adulatory biography, whose hyperbolic subtitle describes Brown as the man who ‘killed slavery, sparked the Civil War and seeded Civil Rights’. Brown was recently the subject of a TV series, The Good Lord Bird, starring Ethan Hawke. Brands writes that his students in Austin, Texas, ‘can’t get enough of John Brown’.

Lincoln and Brown both hated slavery but that conviction by itself did not tell a person how to take action against it. When the Fugitive Slave Act became law, Brown formed the League of Gileadites, a mostly Black group pledged to armed resistance. Later, he spirited a group of Missouri slaves to freedom in Canada. Lincoln, by contrast, insisted that no matter how reprehensible, the law must be obeyed. When the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 opened territories in the Trans-Mississippi West to the expansion of slavery, Brown armed himself and headed there with several of his sons to take part in the local civil war over slavery known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’. During this preview of the national conflict they murdered five pro-slavery settlers. Lincoln joined the new Republican party and committed himself to seeking legislation that barred slavery’s expansion.

A skilled narrative writer, Brands offers a vivid account of the raid on Harper’s Ferry and its aftermath. In military terms, the event was a disaster. No slaves rose up to join Brown (in fact there weren’t very many in the mountains of what is now West Virginia, where the arsenal was located, far from the plantation belt). After commandeering weaponry, Brown abandoned his plan to retreat into the Alleghenies and fight a guerrilla war against the slave system. Instead, he and his men remained in place and were quickly overwhelmed by local militia and a contingent of Marines led by Robert E. Lee. But Brown’s demeanour at his trial for treason, where he cited the Bible as his inspiration, and his subsequent execution, made him a martyr in the eyes of many Northerners. He had made the gallows ‘as glorious as the cross’, Ralph Waldo Emerson exclaimed. Lincoln, the lawyer and constitutionalist, saw the raid as a setback for the anti-slavery cause and strove to dissociate the Republican party from Brown’s action. Among those who witnessed Brown’s hanging was the actor John Wilkes Booth, later Lincoln’s assassin. He called Brown ‘a man inspired, the greatest character of the century’, and resolved to outdo him.

Lincoln and Brown differed not only on strategy but on underlying principles. Unlike Lincoln, Brown saw the struggles against slavery and racism as interconnected. He was determined to live an anti-racist life. Richard Henry Dana Jr (the author of Two Years before the Mast) was astonished when visiting Brown’s farm in upstate New York to find Black guests seated at the dinner table. Brown introduced them not by their first names but as ‘Mr’ and ‘Mrs’. It was obvious to Dana that they had not been spoken to that way very often in their lives. Brown was inspired by the example of black abolitionists, many of whom he knew well, and by slave rebels such as Nat Turner. His armed band was interracial, although Brands tells us little about the motives and goals of the five black men who fought at Harper’s Ferry. Brands observes that one of the reasons Lincoln promoted colonization, despite recognizing the near impossibility of transporting millions of men, women and children out of the country, was that history offered no example of ‘a successful biracial republic’. Brown, however, thought the United States could become just that.

Both Brands and Reynolds conclude their books by noting that the paths chosen by Lincoln and Brown eventually seemed to converge. In 1864, convinced he would not win re-election because of Northern war weariness, Lincoln proposed that the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass raise a force of soldiers who would move into the South, spread word of the Emancipation Proclamation, and encourage slaves to seek freedom behind Union lines. The idea bore a striking resemblance to Brown’s original plan at Harper’s Ferry.

Today, Lincoln is widely revered, while many Americans, including some historians, consider Brown mad. Yet it was Brown’s strategy that brought slavery to an end. In a note written shortly before his death, Brown wrote: ‘The crimes of this guilty land will not be purged away but with blood.’ And Lincoln, the centrist politician, ended up presiding over slaughter on a scale neither he nor Brown could possibly have imagined. At his Second Inaugural, in March 1865, Lincoln embraced Brown’s penetrating insight that slavery was already a system of violence and so could not be eradicated peacefully. Echoing Brown, Lincoln explained the Civil War’s staggering death toll as divine retribution for two and a half centuries of ‘blood drawn by the lash’. He was reminding his listeners that violence in America did not begin when John Brown unsheathed his sword; it was embedded in slave society from the outset. And in the end, as Brands concludes, ‘Union arms, not Union arguments, overthrew slavery.’

[Eric Foner is DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History at Columbia University.]