What Are Identity Politics? A Vision of Solidarity Rooted in Black Feminism

“I have often wished I could spread the word that a movement committed to fighting sexual, racial, economic and heterosexist oppression, not to mention one which opposes imperialism, anti-Semitism, the oppressions visited upon the physically disabled, the old and the young, at the same time that it challenges militarism and imminent nuclear destruction is the very opposite of narrow.”

The 2020 uprisings against police violence offered a direct challenge to systemic racism and a demand for revolution. Many of the overwhelmingly young and incredibly diverse group of protesters not only demanded defunding the police but also made implicit calls for Black liberation that aren’t possible under capitalist society. Those calls are ongoing.

The underlying racial and class politics of this moment share a lot in common with the Black feminist goal of ending all forms of oppression and the socialist objective of overthrowing the existing power structure. Black feminists have long advanced the argument that since our freedom is tied together, we must develop liberation strategies to free everyone.

Black feminism has produced an influential analysis and approach to combating all forms of oppression — particularly patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism — within a common struggle known as identity politics. This is a form of politics that can be called feminist, anti-racist, and anti-fascist. Black feminists’ goal has never been to increase the power and influence of women who are already the most elite. Instead, they’ve sought to do the opposite by building power among the least privileged women.

Today, Black feminist books, interviews, and writings circulate on a massive scale, reaching well beyond academic or activist circles. The leaders of many prominent activist groups, including Black Lives Matter, speak openly about how identity policies and Black feminism have informed their strategies and campaigns today. Furthermore, Black feminist political endorsements are seen as coveted in recognition of their forward-thinking leadership and political vanguard status.

Black feminism is the politics of the moment. Now is a perfect time to uncover the real meaning of Black feminist identity politics.

The history of Black feminism is closely tied to Black women’s unique experiences in the civil rights, Black freedom, and feminist movements — all of which tended to neglect issues of direct concern to Black women. This marginalization motivated the creation of what can be called second-wave Black feminism. The battle for civil rights could not have been possible without the Black women theorists, strategists, and shock troops who put in the daily work.

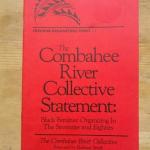

In 1974, Barbara Smith joined with a group of radical Black lesbian feminists to found the Boston-based Combahee River Collective (CRC) as a more left alternative to the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). Although the NBFO was socialist in its beliefs, the CRC distinguished itself as a farther-left anti-capitalist revolutionary organization.

CRC is most well-known for writing the 1977 Combahee River Collective statement, a fundamental document in constructing the concept of identity as a basis to organize. The statement lays out a commitment to fighting racism, sexism, class oppression, and homophobia. It argues that these are interrelated forces, stating that “the synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives.”

The statement includes the following points: As Black women, members of the collective resolved to work with Black men to fight against racism, and they committed to challenging Black men on sexism. As feminists, they would continue to be involved in the feminist movement but call on white women to take responsibility for eliminating racism within that movement. As lesbians, they fought against homophobia on its own and within those other two movements. Finally, as socialists, they affirmed the importance of labor organizing and believed that workers should control their workplaces.

Notably, the CRC coined the term identity politics as a framework that came “directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.” As Mychal Denzel Smith argues in the New Republic, some have taken this to mean that Black feminists are only interested in advocating for Black women, and that identity politics are actually very narrow. But what they believed, and what they write later in the statement, is that “if Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” All the systems that oppress Black women oppress everyone else too. CRC never defined identity politics as exclusionary or intended to mean that only those who experience a certain oppression can fight to end it.

In Black Feminist Politics From Kennedy to Clinton, Duchess Harris cites one CRC member who had this to say about identity politics: “This was the kind of politics that had never been done or practiced before to our knowledge…it had never been quite formulated in the way that we were trying to formulate it, particularly because we were talking about homophobia, lesbian identity, as well. There were politics that took everything into account as opposed to saying leave your feminism, your gender, your sexual orientation, you leave that outside.…We meant politics that came out of the various identities that we had that really worked for us. It gave us a way to move, a way to make change. It was not the reductive version that theorists now really criticize.…We took on the contradictions of being in the U.S. and living in U.S. society under this system.…And we said, instead of being bowled over by it and destroyed by it, we are going to make it into something vital and inspiring.”

As Black women, feminists, and socialists, the CRC did not think of identity-based movements as wedge or separatist, but as opportunities to build real power.

In the five years the collective was active, it brought significant gains for all women living in the Boston area while successfully using members’ identities as Black women as a basis for organizing. The extent of the CRC’s political activities affirmed the members’ understanding of various oppressions. Harris lists the following political projects: They joined the movement to free Ella Ellison, a woman accused of murdering a prison guard at Framingham State Prison; supported Kenneth Edelin, a Black doctor wrongfully charged with manslaughter for performing an abortion at Boston City Hospital; and picketed in solidarity to ensure the hiring of Black workers.

CRC worked to bring media attention to the Roxbury murders, in which 12 Black women and one white woman were found dead in the Roxbury-Dorchester neighborhood. CRC produced a collection of pamphlets condemning the homicides and pointing out the racial and sexual violence faced by women of color. Barbara Smith argued that “if you are married or heterosexual, whatever, all kinds of women are at risk for attack in different kinds of circumstances. And in fact, most women are attacked by the men they know.” CRC organized both a rally that brought hundreds of people to the streets and pressured the Boston Globe to move its coverage of the murders from its sports section to headline news.

Certainly, the collective’s work had immense results, concerning not only the oppression of Black women but all women in the Boston area.

In the essay “Identity Politics and Class Struggle,” Black Marxist Robin D.G. Kelley credits the Chicano and Asian American movements, the LGBTQ+ movement, and the Black feminist movement with producing very radical theories and practices. He claims that identity politics is people fighting for environmental justice for the inner city, workers resisting racism in unions, men advocating for women’s rights, and straight people raising their voices against homophobia. To dismantle all forms of oppression, we need to unite the entire working class, and identity politics provides us with a way to do that.

Black feminists and activists of color insisted that revolutionary change could emerge from privileging what were seen as wedge issues by some on the American left, like sex, race, and gender. Kelley uses the example of the National Black Women’s Health Project, a nonprofit organization formed in the early 1980s in Atlanta to address African American women’s health and reproductive rights. This project grew out of the Black women’s health care movement, which aimed to establish a better climate for poor and low-income women and lessen Black women’s reliance on a medical system organized by private enterprise and controlled mostly by men. Their success would have led to a massive transformation that would have benefited everyone, irrespective of race or gender.

Black feminists’ refusal to submerge their identities into insipid, ahistorical calls for unity has blossomed into anti-fascist, anti-racist work worldwide. The influence of these concepts can be seen just about everywhere. They developed an analysis of power, which shows oppression is rooted in and exacerbated by many systems. Thinking of social inequality or oppression in terms of various interconnected prejudices allows us to develop liberation strategies based on how power truly operates. Intersectionality acknowledges that power is dispersive and comes from many sources.

Today Black feminism and the notion that solidarity means to fight for someone you don’t know are almost taken for granted. The Black feminist call for solidarity based on difference invites us to look at hierarchies of class, gender, and race — and how these hierarchies impact both individuals and collectives. It has the power to foster solidarity and make our movements stronger. Solidarity doesn’t mean subsuming your battles to help another person; it means taking political responsibility to fight against struggles.

Marian Jones is an NYC-based community organizer, writer and editor at Lux Magazine. Her work focuses on black feminism, reproductive justice, prison abolition.