Alice Neel’s Communism Is Essential to Her Art. You Can See It in the ‘Battlefield’ of Her Paintings, and Her Ruthless Portrait of Her Son

Alice Neel painted “the human comedy.”

It’s a phrase she repeated often in interviews and in text, throughout her life. It is the title of one of the sections of “Alice Neel: People Come First,” her outstanding and moving retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In one sense, what she meant is obvious. Memorable and interesting characters abound in her paintings, running from her many lovers to the luminaries of New York’s Depression-era political and literary Left; from art celebrities like Andy Warhol to her acquaintances in the East Harlem neighborhood where she toiled in obscurity for decades; from the feminist activists and critics who championed her work in the ‘60s and ’70s to her own self, shown naked, at 80, paintbrush in hand and gazing skeptically out at the viewer as if sizing them up—one of the most indelible of all 20th-century self-portraits.

The text in the Met’s “The Human Comedy” gallery explains that she meant the phrase as a reference to French author Honoré de Balzac’s story collection La Comédie humaine, “which examines the causes and effects of human action on nineteenth-century French society.” It notes that Neel wanted to chronicle “suffering and loss, but also strength and endurance,” as Balzac did.

Which is… fine, as far as it goes, and falls in line with the show’s framing of Neel as an “anarchic humanist.” But the “effects of human action” is a pretty vague phrase. As opposed to what? The effects of the movement of the planets?

The truth is that the words “the human comedy” had a lasting magic for Alice Neel because Alice Neel thought of herself as a Communist intellectual. Every artist with an interest in Marxism would have gotten the reference, because almost all of Communist aesthetic theory looked for legitimacy, in one way or another, to Marx and Engels’s approving remarks on Balzac’s La Comédie humaine.

The authors of the Communist Manifesto thought Balzac captured not just the spirit of his time, but provided a portrait of the pathologies of bourgeois society, the toll that money took on human relations (despite Balzac’s aristocratic personal politics).

Interviewed by the Yale Press podcast, the exhibitions’s curators, Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey, seem very concerned with emphasizing that Neel’s politics were “independent,” “non-dogmatic,” and that her affinities for Communist ideas softened as she aged. Which may be true: Times change, people change, art and politics and how they intersect change.

“You see, it’s not so much that I am pro-Russia as that I am pro-détente,” she said onstage towards the end of her life. But she also said, around the same time, “Reagan has said the government doesn’t owe anybody anything. In the Soviet Union you get free medical care—everything is free. There the government owes you everything.”

In 1981, just three years before she died, she contributed to a fundraiser for the Reference Center for Marxist Studies, a depository for Communist Party history located in the headquarters of the attenuated CPUSA. The same year she actually did a show in Moscow at the Artists’ Union, organized by Philip Bonosky, the Moscow correspondent for the Daily World, which was the successor to the CP’s Daily Worker. (She had painted him three decades earlier, when he was editor at the Communist magazine Masses & Mainstream.)

Interviewed at the age of 82 by art historian Patricia Hills, Neel was still making the case for the significance of her portraiture by referencing Vladimir Lenin’s respect for Balzac’s The Human Comedy (she kept a poster of Lenin in her apartment all her life, according to Phoebe Hoban’s 2010 biography) as well as Hungarian Marxist Georg Lukács’s advocacy for Thomas Mann.

Neither Lenin nor Lukács were names you brought up in the 1980s to win points for being with-it, artistically or politically.

Rather than trying to fit Neel into the framework of a rose-colored contemporary progressivism, it seems much more interesting—and more accurate—to consider how the artist’s actual, passionately felt, difficult allegiances shaped her: the sacrifices she made in her life; the specifics of her art; and her relation to the New Left feminist movements of the 1960s and ’70s that pulled her from obscurity, and that now probably overdetermine the reading of her work still.

Depression Decades

Born into small-town Pennsylvania respectability in 1900, Alice Neel went to study art at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women looking for a more interesting life. “I came out of that little town the most depressed virgin who ever lived,” she remembers in a 2008 documentary directed by her grandson. She met and married Carlos Enríquez, a soon-to-be-important Cuban painter, and travelled to Cuba in 1926, where the sight of poverty in pre-revolutionary Havana radicalized her.

Returning to New York, she suffered the loss of her first child, Santillana, to diphtheria—the subject of the ghostly Futility of Effort (1930), later featured in a 1936 issue of the journal of the Artists Union, Art Front, retitled as Poverty. The couple would separate, and Enríquez would take their second child, Isabetta, back to Cuba.

New York’s Greenwich Village was where Neel found her most lasting community, in the demimonde that swirled together leftist radicals and artistic strivers amid the hardship brought on by the Great Depression.

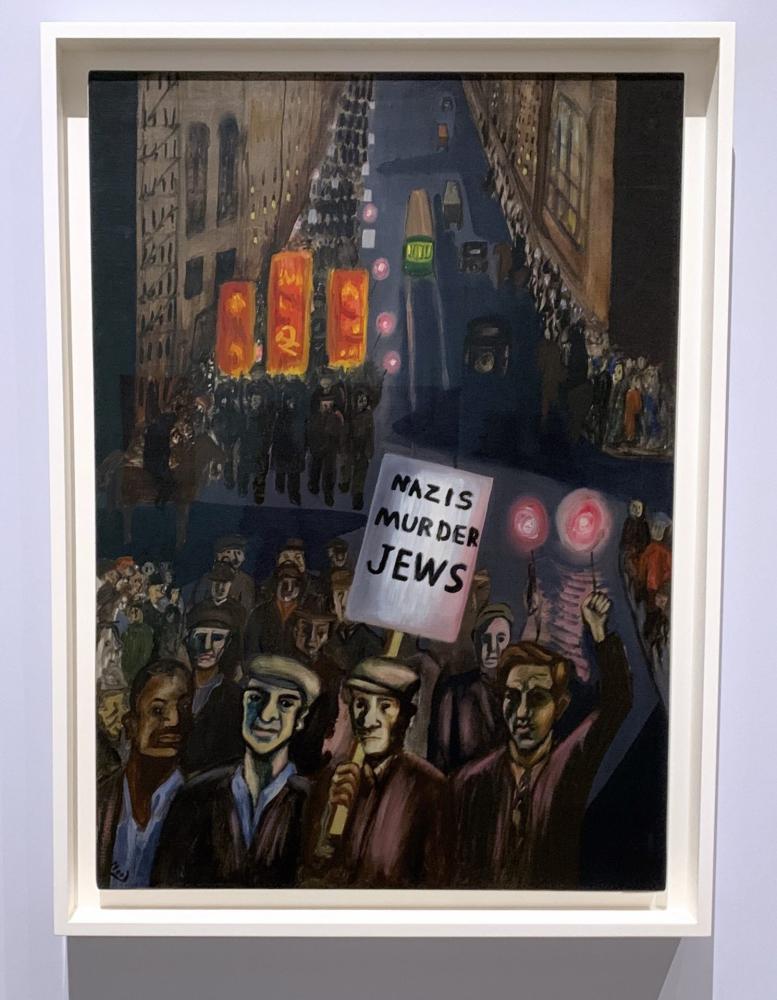

When the New Deal’s art projects started up in ’33, Neel seized the opportunity as a lifeline, painting a canvas every six weeks on government wages, her eye turning for a time to urban scenes and public demonstrations in the mode of the day.

(An anecdote she liked to tell later in life is that Harold Rosenberg, the critic of abstraction, schemed his way onto the government payroll by submitting two Neel paintings as his own, before becoming an art writer.)

The Communist Party was enthusiastic about the New Deal Arts Projects and a force in pushing for their expansion, and Neel soon joined “the Party.” It might surprise us now that a figure of Neel’s scrappy, bohemian independence would be drawn to the CP, even given the fact that she joined in ’35, when the USSR’s foreign policy needs aligned with Roosevelt’s agenda, and the turn to the Popular Front opened the doors for fellow-traveling artists of all kinds.

But Cold War dogma and our knowledge of the actual evils of the Soviet system cloud our assessment of the Communist Party’s on-the-ground profile at the time. Its opposition to US social order led it to engage with both racism and sexism in ways that mainstream institutions often wouldn’t. As Andrew Hemingway writes in his great history of the time, Artists on the Left, Neel “is representative of that type of woman artist and intellectual who gravitated to the CP because—whatever its limitations—it offered the most sustained critique available of class, racial, and sexual inequality.”

Neel’s role model would have been someone like Ella Reeve Bloor, aka Mother Bloor, the most well-known female leader in the CPUSA in the ‘20s and ‘30s. Born 1862, Bloor was a formidable organizer who supported six children while divorcing and marrying as she pleased. She was a comrade of Eugene Debs and Upton Sinclair, and her labor journalism inspired Woody Guthrie’s song about the Ludlow Massacre. In her sixties, during the Great Depression, Bloor toured the Great Plains with her son, organizing farmers.

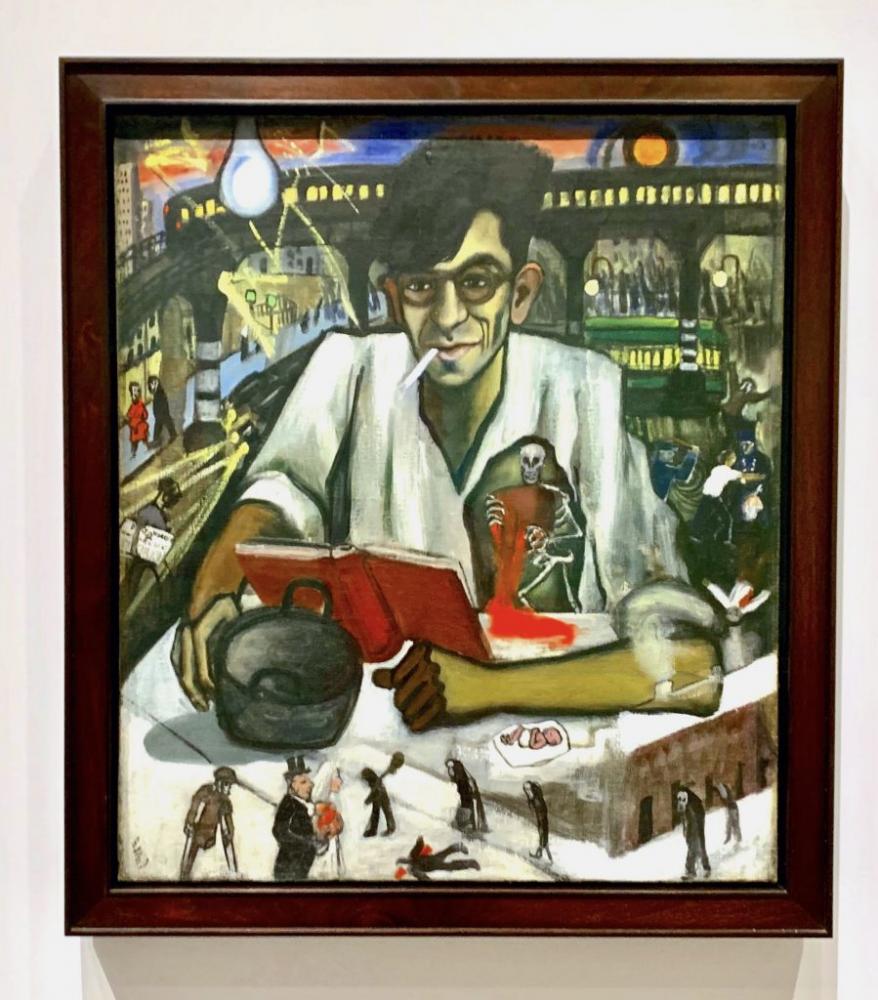

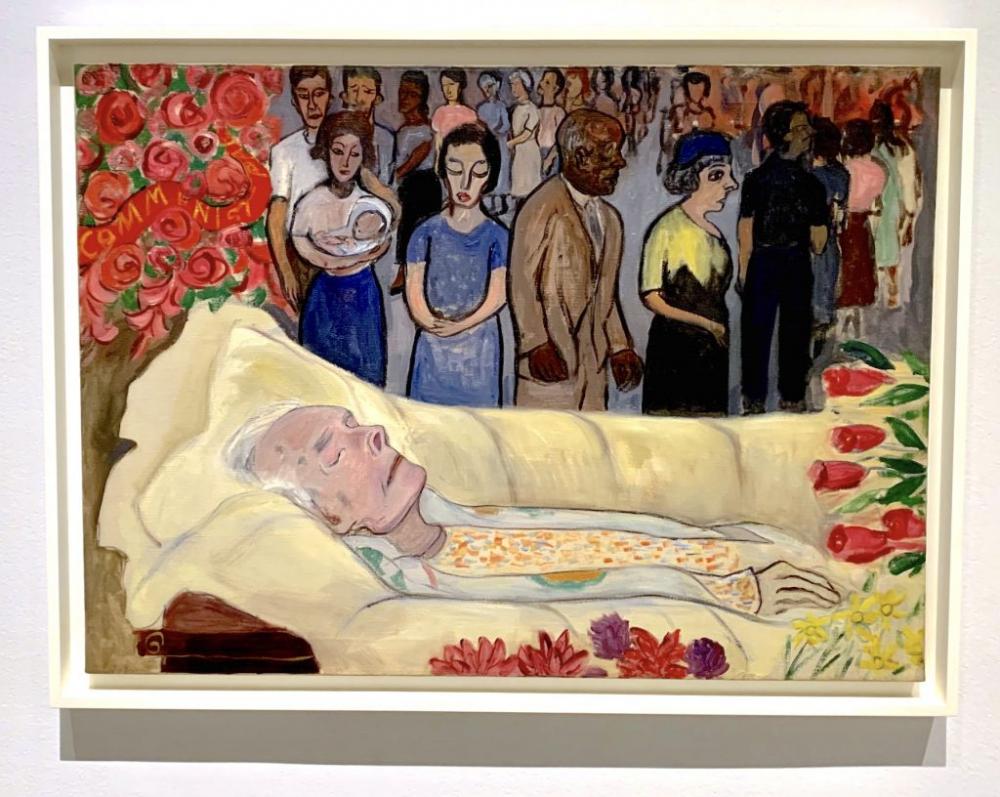

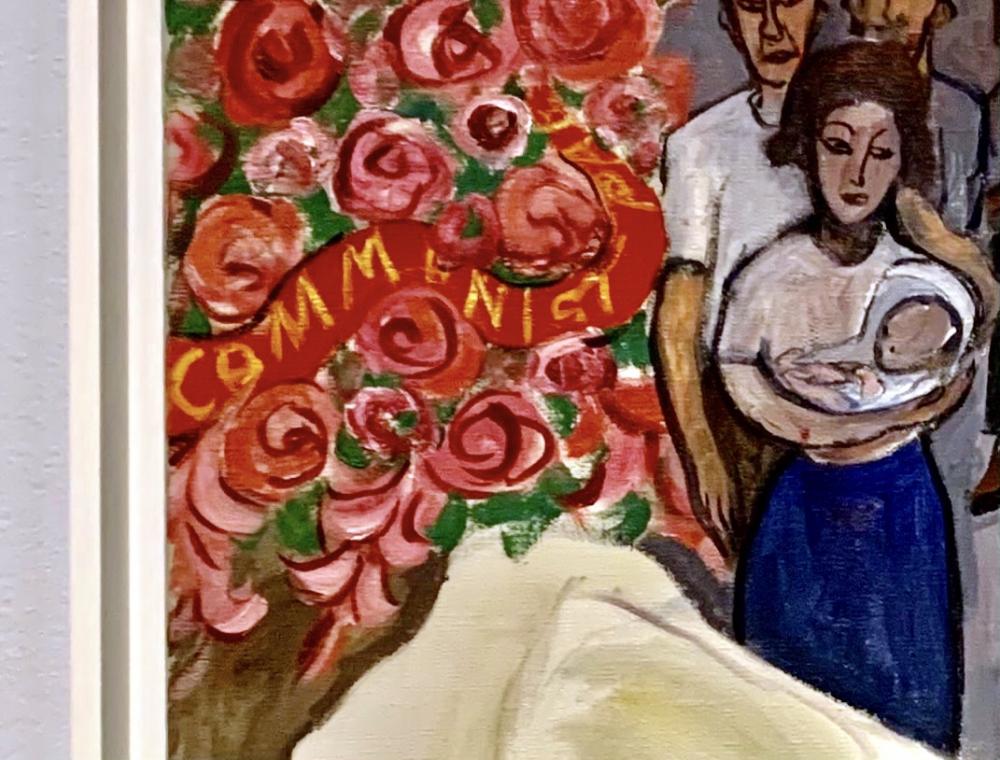

Neel painted Mother Bloor’s funeral in a 1951 work. She is pictured, sainted, in a coffin as a multiracial crowd of mourners files past. A wreath above her head reads “COMMUNIST,” the word “PARTY” vanishing as it wraps around a bouquet of roses.

Keeping the Faith

The curators of “Alice Neel: People Come First” cite approvingly a line by Neel saying that she was “never a good Communist,” because she hated “bureaucracy” and the “meetings used to drive me crazy.” But a distaste for bureaucracy or political meetings doesn’t mean she didn’t imbibe the party line. (It just means she was an artist.)

In the very same interview Neel also stresses that “it [the Communist Party] affected my work quite a bit.”

It’s one thing to join the Communist Party at a time when Communist ideas were in vogue with the artistic mainstream, and capitalism was in a crisis that was plain for all to see. Many did in the Depression years. But Neel remained faithful to the movement long after.

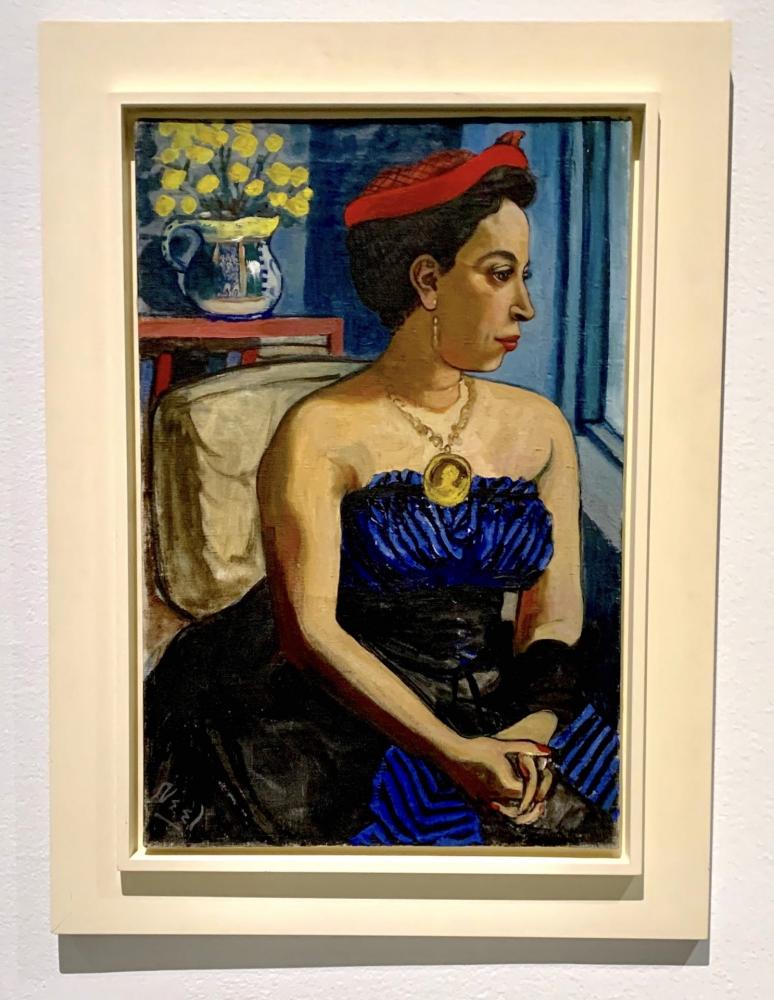

Alice Neel, Alice Childress (1950). Photo by Ben Davis // Artnet News.

In the ‘40s and ‘50s, she studied philosophy at the Jefferson School for Social Research, an adult education school in New York run by the Communist Party. She delivered some of her first slide lectures about her art there.

One of her teachers, V.J. Jerome, chair of the Party’s Cultural Commission, was convicted under the Smith Act for his 1950 pamphlet “Grasp the Weapon of Culture!,” which described mass culture as anti-human and a narcotic polluting the masses, arguing the need for a revolutionary art to bring down capitalism. Neel made sure to visit Jerome to show support after he was released from jail.

This was the high tide of McCarthyism, when most others of the so-called “New York Intellectuals” were abandoning their earlier, ‘30s-era Marxist commitments and turning hard towards Cold War liberalism and anti-Communism.

And yet the very title of the Met show, “People Come First,” comes from a line in a 1950 Daily Worker interview with Mike Gold, the foremost propagandizer of proletarian art in the United States. Even as Abstract Expressionism was being coronated at MoMA, Gold had quoted Neel: “I am against abstract and non-objective art because such art shows a hatred of human beings.”

(Incidentally, when figuration reemerged in the art world in the late ’60s, it was in the form of Photorealism—and Neel hated that too. She argued that it also sinned by treating humans the same as things, replicating capitalist ideology. She thought special attention should be reserved for the human. Her particular Marxist aesthetic, therefore, gives insight into the ways she set her subjects off from less defined backgrounds and the meaning she gave to the expressive, painterly qualities of her paintings in that era.)

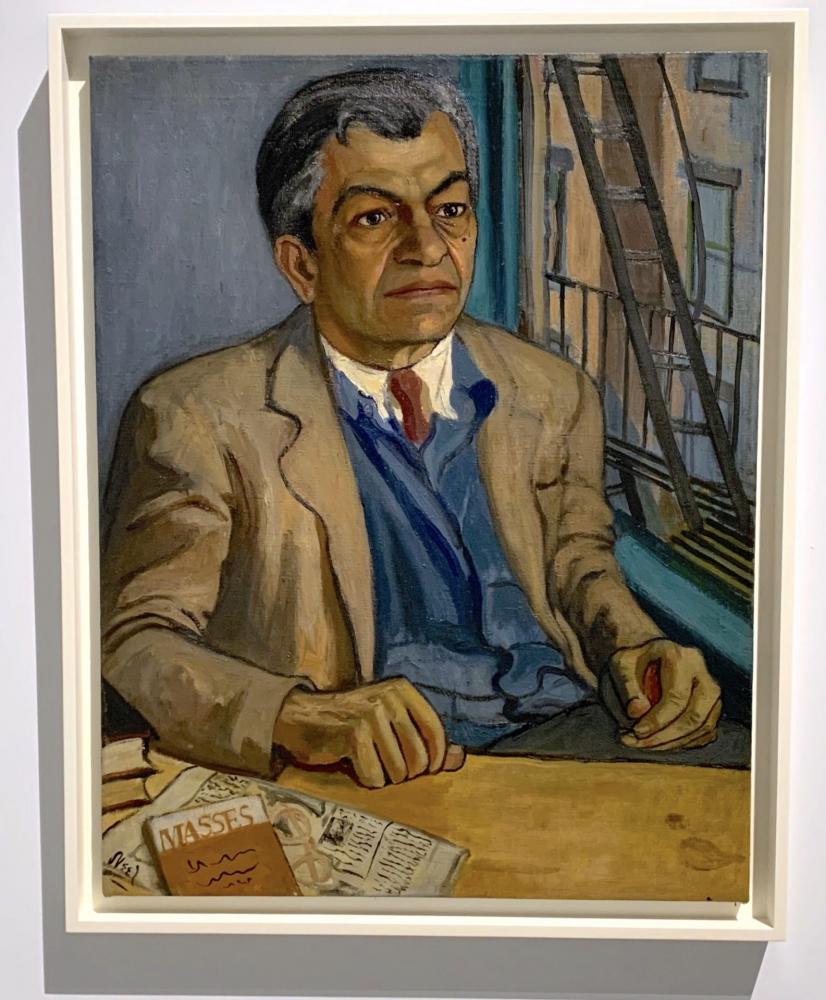

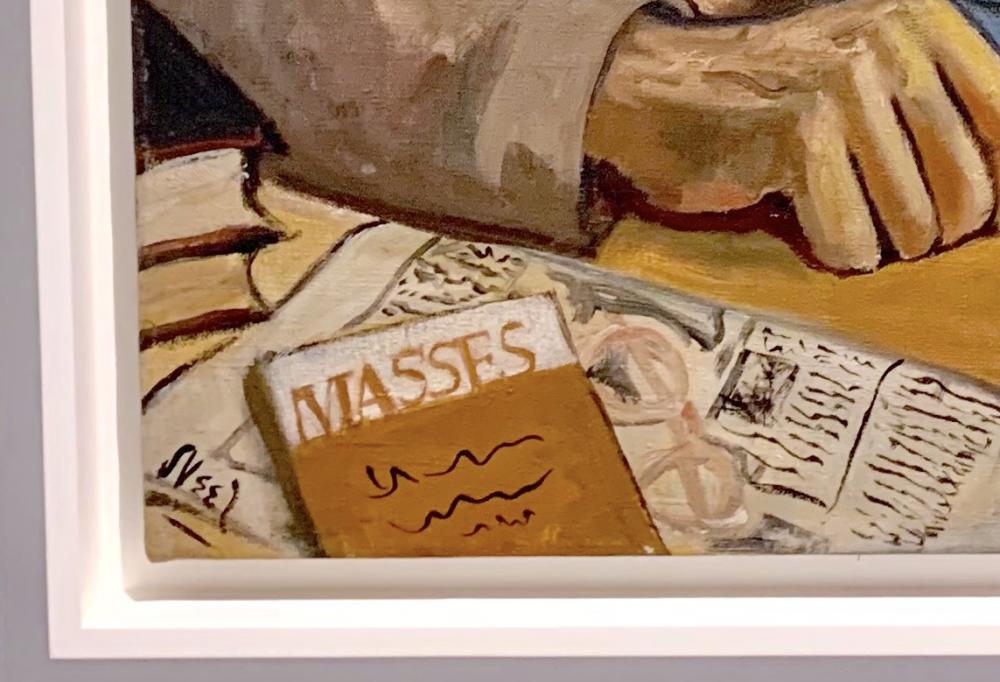

Gold championed Neel as a “pioneer of socialist-realism in American painting,” and she returned the love with a portrait from 1951. His weathered, tan features appear thoughtful and ready for debate. Depicted on the table before Gold in Neel’s painting is a copy of the Communist intellectual journal Masses.

Beneath that is a newspaper. In what I take to be a deliberate suggestion of Neel’s continuing alignment with Gold’s output as a writer and propagandist, she has placed her own signature as if it is a part of the newspaper.

Neel had moved to Spanish Harlem in 1938 with her lover, the singer José Santiago Negrón (whom she had met when she was 35 and he a decade younger). For her, the paintings she did of neighbors, acquaintances, and comrades from the Puerto Rican community weren’t just sentimental or picturesque. Works such as Mercedes Arroyo, The Spanish Family, and T.B. Harlem made their debut in a show at the Communist-controlled New Playwrights Theatre, with an essay by Gold, and were presented explicitly as part of a Communist political-cultural project, bound up with the Party’s advocacy—and sometimes fetishization—of Third World struggle.

Gold quoted Neel like so: “East Harlem is like a battlefield of humanism, and I am on the side of the people there, and they inspire my painting.”

A Difficult Rebirth

In the popular imagination, the story of the ‘60s New Left movements is that they raised issues of race and gender that the Old Left’s idealization of a white male factory worker had ignored. But it’s a little more complicated than that.

An interesting twist highlighted by recent museum shows reconsidering this period is that, as it turns out, the artists who were adopted as the most vital, heroic exemplars by the insurgent ‘60s social movements had, in fact, often been forged by the Old Left artistic scene. It was in terminally uncool Social Realism that the idea of an art that honored the experiences of the suffering, oppressed masses had been preserved and could be picked up again when new social movements rebelled against the reining formalism.

Charles White, the masterful social realist who was affiliated with the CPUSA until 1956 and was nurtured in some of the same Communist spaces and periodicals as Neel, was an example for the Black Power generation. Neel was an example for Women’s Liberation.

The Communist Party had all but imploded after Khrushchev’s secret speech in 1956 revealing Stalin’s crimes. Without the new feminist movement, there would have been no Neel revival.

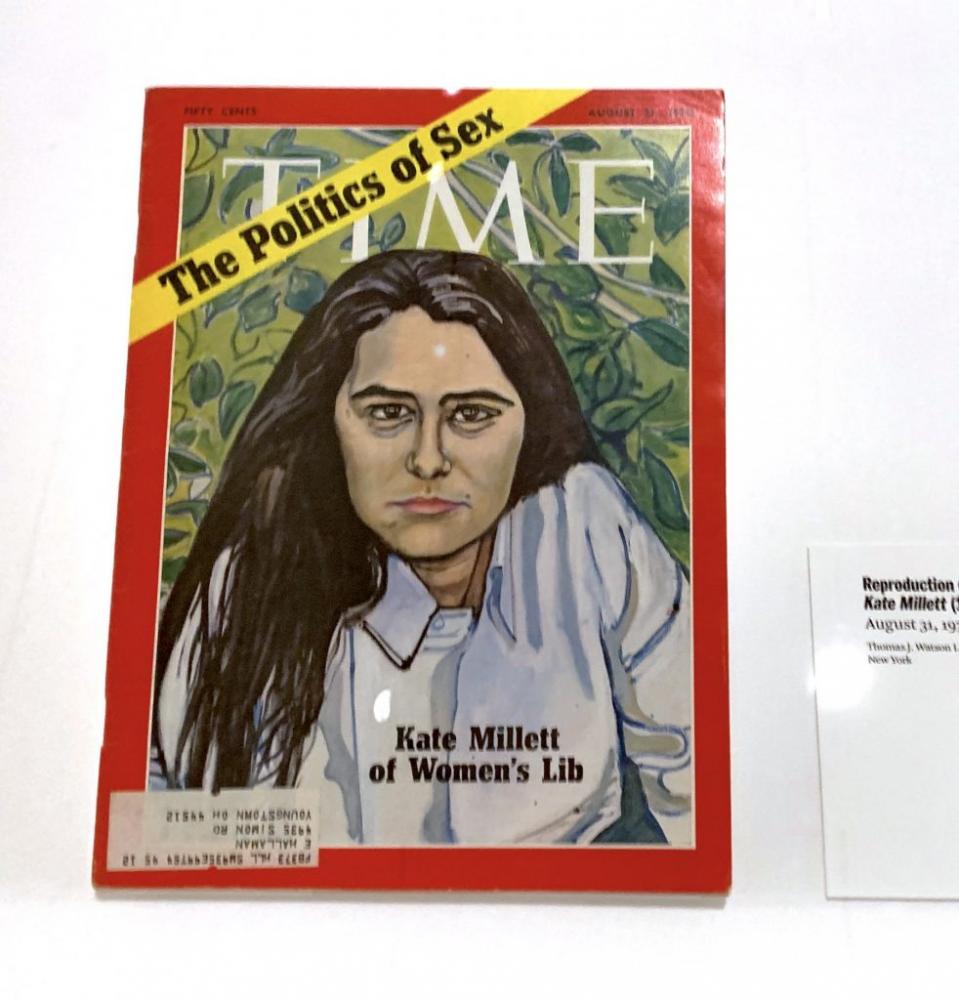

Neel, in turn, helped shape the image of the ascendant movement, doing a steely painting of writer Kate Millett for the 1970 cover of Time magazine on “The Politics of Sex,” just as Women’s Liberation was moving into mainstream consciousness.

She painted the luminaries of the feminist movement as faces of their time, just as she had painted the earlier Communist intellectuals: art historians Linda Nochlin (with daughter Daisy) and Cindy Nemser (nude, with husband Chuck, also nude), Redstockings founder Irine Peslikis (described as “Marxist Girl”), and many more.

Neel also did numerous images of women nursing and pregnant nudes, among her most celebrated works. Here, her eye for honoring the realities of ordinary people’s lives hidden beneath bourgeois ideology met the feminist project of honoring the hidden world of women’s work beneath the sentimental domestic cliches.

But Neel also had a famously difficult relationship with the Second Wave of feminism, even as she reveled in its attention and clearly believed in the importance of Women’s Liberation. Partly, this was generational. Like Georgia O’Keeffe (though a quarter-century younger) or Joan Mitchell (though a quarter-century older), Neel had spent a lifetime trying to escape the stigma of being patronizingly reviewed as a “lady painter,” and was suspicious of being touted for her gender.

But this was also partly political, inscribed in the very creed that had allowed her to hack it out all those lonely, unrecognized, pre-feminist-movement years. She had chosen a life of poverty out of an ideological belief in solidarity with the working class and the oppressed. With a combination of insight and narrow-mindedness, she considered a lot of the preoccupations of the new feminist artists she encountered to be self-absorbed and trite—in a word, “bourgeois.”

In 1970, her work was included in the Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin-curated “Women Artists, 1550–1950” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The show had been the product of actual protests by feminists, who had threatened a Civil Rights complaint against the museum for not showing women.

Yet reflecting on the show’s reception, Neel was characteristically salty and dismissive of those who didn’t share her fundamental political outlook:

What amazed me is that all the woman critics—you see, you are very respected if you paint your own pussy, as a woman’s libber. But they didn’t have any respect for being able to see an abused Third World. So nobody mentioned that I managed to see beyond my pussy politically. But I thought that was really a good thing if they had a little more brain.

The Era of the Corporation

There is ego here: Alice Neel was never shy about saying why her art was better than anyone else’s. But the judgement flowed directly from the Marxist theory she used to understand her practice, which held that capitalist life kept us wallowing in immediate subjective experiences, unable to generalize and so unable to change the world. In Georg Lukács’s 1938 essay “Realism in the Balance,” he had written:

f we are ever going to be able to understand the way in which reactionary ideas infiltrate our minds, and if we are ever going to achieve a critical distance from such prejudices, this can only be accomplished by hard work, by abandoning and transcending the limits of immediacy, by scrutinizing all subjective experiences and measuring them against social reality. In short it can only be achieved by a deeper probing of the world.

You can see how this artistic theory of hard looking would resonate with Neel’s sense of what a portrait should be. Lukacsian realism was about neither simply life-like description nor the depiction of ordinary experiences in an accessible way; it was about art that moved through the specific case to a revelation of the overall social context that had shaped its meaning and identity.

When, in the Hills interview, Neel says that what she values most in her own art is that she tries to paint “the complete person” but also, though that depiction, to capture the “spirit of the age,” it is just such an operation she seems to have in mind.

“The favorite author of Georg Lukács was Thomas Mann,” Neel continues, “because Mann could see how sick the world was. But the sickness has now been transformed into junkiness. You see, the character of this era is its utter lack of values.”

How seriously did Alice Neel take the mission of her art to capture its time, which went considerably beyond the personal satisfaction she got from organizing paint on canvas or communing with her many interesting sitters?

So seriously that, when it came time to paint the character of the ‘70s and its “utter lack of values,” she would show it in the face of her own adult son.

Having lost two daughters, Alice Neel raised two sons on welfare, in poverty, all while committed to making unsellable art. In the 2008 documentary, Richard Neel remembers Alice tolerating a lover, Sam Brody, who beat him, because she was dependent on him for money and he flattered her artistic ego. Burned by the dispiriting instability of their upbringing, both sons would reject her communist and bohemian values, steering clear of the new movements of the ‘60s even as they elevated their mother. They became, respectively, a doctor and a lawyer—as solidly middle class as you can get.

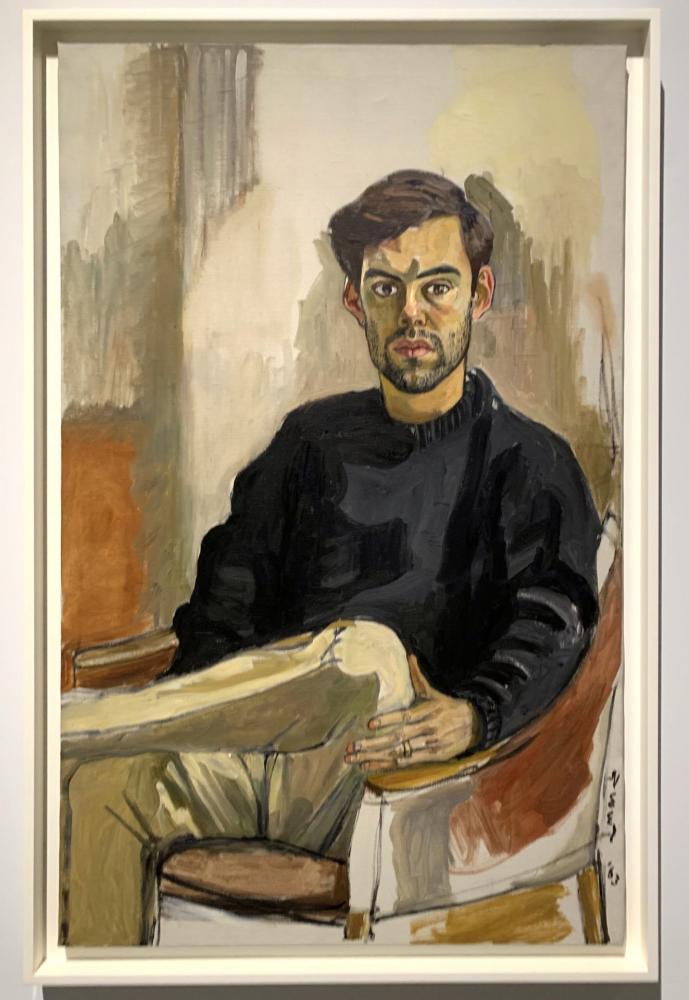

She had painted Richard warmly in the handsome Richard (1962), when he was 24, with five o’clock shadow and a casual sweater.

By the time Richard evolved into the late-period Richard in the Era of the Corporation (1978-79), the real Richard had become an ardent Nixon supporter and chief executive council for Pan Am Airways. In the year she made the painting, Pan Am was okayed by Jimmy Carter’s Airline Deregulation Act to snap up National Airways for $437 million.

“There are very few people as right-wing as I am,” Richard says in the 2008 documentary. His mother would say that Richard in the Era of the Corporation was her attempt to capture how “the corporation enslaved all these bright young men.”

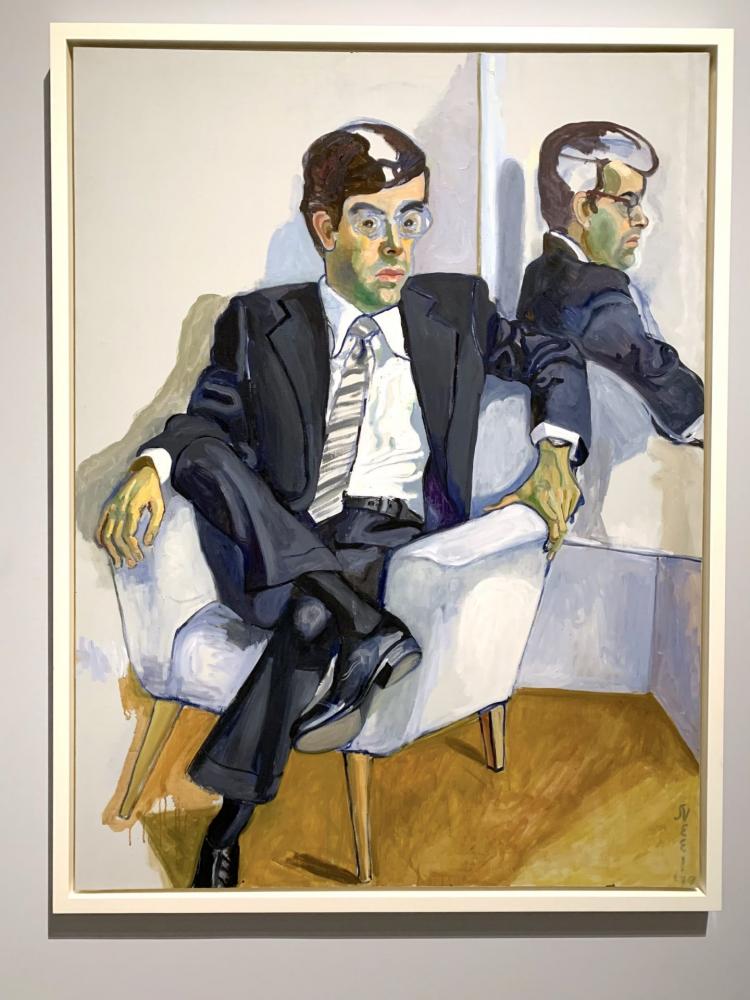

Now 40, Richard is shown again on a chair, this time in suit and tie. Compared to the earlier composition, this one is one step farther back, less intimate; the warm brown palette has yielded to a slightly icy climate.

Splashes of green linger around the mouth. Green veins trace his hands.

The 1979 Richard projects cool assurance, his legs casually crossed as before—but the foot is suspended at a strained angle. He’s literally twisted.

The white patches in the hair in both the figure and his reflection suggest a man graying into middle age, but also make him look as if he is fading away or that something is literally missing from him.

But it’s his eyes that I notice. Childhood malnourishment had left Richard’s eyesight damaged. Uniquely among her bespectacled sitters (compare her own self-portrait from a year later), Neel has given Richard shark eyes, all pupils. His glasses, strangely left unfinished, float unevenly around them, agitated halos, as if he were spellbound or hypnotized.

Neel rightly gets credit for painting aspects of female experience that hadn’t gotten a lot of play in art before, in her pregnant nudes and nursing mothers and scenes of childbirth. Richard in the Era of the Corporation’s depiction of political estrangement between mother and son is another intimate experience I am not sure had ever been depicted.

And this painting was telling, not just in terms of capturing a mood among the Neel family but in terms of capturing the larger zeitgeist.

The story of the backlash against the movements of the 1960s by the rising generation and the consolidation of corporate hold over life was indeed the story that defined the decades to come—with so many horrible consequences.

“I love, fear, and respect people and their struggle,” Neel told Hills in 1982, “especially in the rat race we live in today, becoming every moment fiercer, attaining epic proportions where murder and annihilation are the end.”

False Choices

Finally, why bother spending so much time on Alice Neel’s Communist affinities?

There’s enough Neel to go around in this show: There’s an erotic Neel; a familial Neel; a Neel as painter of wonky domestic still-lifes. But clearly we are more comfortable with these aspects of her work and are embarrassed by the Communism, rendering it as a soft-focus “radicalism” or classless “feminism” that she herself would have hated.

The topic is worth lingering on, but not because you need to defend Communism to defend Marxism or activism. The opposite is closer to the truth, in my opinion. For the entire period Neel was working, there were Marxists and activists who were critical of the CP, critical of the Soviet Union—they were just much less visible than the CP.

But Communism was a motivating passion for Neel. Its sense of destiny kept her going. Its theory offered a model of intellectualism that was committed to speaking to ordinary people. It offered critical insights that weren’t easy to find elsewhere along with tragic blind spots. (If you are interested in what it felt like to live these difficult dynamics, Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism can’t be beat.)

Neel’s politics were bound up with all that other stuff that made her remarkable. The art-historical dilemmas they leave us with are heritage of the fact that the society she was trying to survive and depict was actually full of awful dilemmas. The best way to honor her as a painter of difficult truths is by not smoothing these over.

[Ben Davis has been artnet News's National Art Critic since 2016. He is the author of '9.5 Theses on Art and Class' (Haymarket, 2013), and was an editor of 'The Elements of Architecture' (Taschen, 2018), which began as the catalogue to the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennial. Recent essays have appeared in the books 'Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good' (MIT Press, 2016) and 'The Future of Public Space' (Metropolis, 2018). His writings have been featured in Adbusters, The Brooklyn Rail, e-Flux Journal, Frieze, New York, The New York Times, Slate, The Village Voice, and many other venues. In 2019, Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab reported that he was one of the five most influential art critics in the United States, and the only one to write for an online publication.]

“Alice Neel: People Come First” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 1, 2021.