Teshuvah: A Jewish Case for Palestinian Refugee Return

In April, when Joe Biden announced that he would restore US funding for The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which provides education, health care, and other services to Palestinian refugees, establishment American Jewish groups reacted with dismay. A letter signed by Hadassah, B’nai B’rith, and the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) blamed UNRWA’s schools for teaching Palestinian refugees “lessons steeped in anti-Semitism and supportive of violence.” AIPAC accused the organization of “inciting hatred of Jews and the Jewish state.”

But AIPAC and the ZOA did not merely accuse UNRWA of miseducating Palestinian refugees. Along with Israeli government officials, they have questioned whether most of the Palestinians that UNRWA serves are refugees at all. AIPAC has slammed UNRWA’s “misguided definition of refugees.” ZOA called UNRWA’s clientele “the descendants of Arab refugees.” Israel’s Ambassador to the US and the UN, Gilad Erdan, declared that, “this UN agency for so-called ‘refugees’ should not exist in its current format.”

The fundamental problem with UNRWA, according to this line of argument, is that it treats the children and grandchildren of Palestinians expelled at Israel’s founding as refugees themselves. Establishment Jewish critics don’t blame UNRWA merely for helping Palestinians pass down their legal status as refugees, but their identity as refugees as well. In The War of Return, a central text of the anti-UNRWA campaign, the Israeli writers Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf allege that without UNRWA, refugee children “would likely have lost their identity and assimilated into surrounding society.” Instead, with UNRWA’s help, Palestinians are “constantly looking back to their mythologized previous lives” while younger generations act as if they have “undergone these experiences themselves.” To Schwartz and Wilf’s horror, many Palestinians seem to believe that in every generation, a person is obligated to see themselves as if they personally left Palestine.

As it happens, I read The War of Return just before Tisha B’Av, the day on which Jews mourn the destruction of the Temples in Jerusalem and the exiles that followed. On Tisha B’Av itself, I listened to medieval kinnot, or dirges, that describe those events—which occurred, respectively, two thousand and two thousand five hundred years ago—in the first person and the present tense.

In Jewish discourse, this refusal to forget the past—or accept its verdict—evokes deep pride. The late philosopher Isaiah Berlin once boasted that Jews “have longer memories” than other peoples. And in the late 19th century, Zionists harnessed this long collective memory to create a movement for return to a territory most Jews had never seen. “After being forcibly exiled from their land, the people kept faith with it throughout their Dispersion,” proclaims Israel’s Declaration of Independence. The State of Israel constitutes “the realization” of this “age-old dream.”

Why is dreaming of return laudable for Jews but pathological for Palestinians? Asking the question does not imply that the two dreams are symmetrical. The Palestinian families that mourn Jaffa or Safed lived there recently and remember intimate details about their lost homes. They experienced dispossession from Israel-Palestine. The Jews who for centuries afflicted themselves on Tisha B’Av, or created the Zionist movement, only imagined it. “You never stopped dreaming,” the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once told an Israeli interviewer. “But your dream was farther away in time and place . . . I have been an exile for only 50 years. My dream is vivid, fresh.” Darwish noted another crucial difference between the Jewish and Palestinian dispersions: “You created our exile, we didn’t create your exile.”

Still, despite these differences, many prominent Palestinians—from Darwish to Edward Said to law professor George Bisharat to former Knesset member Talab al-Sana—have alluded to the bitter irony of Jews telling another people to give up on their homeland and assimilate in foreign lands. We, of all people, should understand how insulting that demand is. Jewish leaders keep insisting that, to achieve peace, Palestinians must forget the Nakba, the catastrophe they endured in 1948. But it is more accurate to say that peace will come when Jews remember. The better we remember why Palestinians left, the better we will understand why they deserve the chance to return.

Even for many Jews passionately opposed to Israeli policies in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, supporting Palestinian refugee return remains taboo. But, morally, this distinction makes little sense. If it is wrong to hold Palestinians as non-citizens under military law, and wrong to impose a blockade that denies them the necessities of life, it is surely also wrong to expel them and prevent them from returning home. For decades, liberal Jews have parried this moral argument with a pragmatic one: Palestinian refugees should return only to the West Bank and Gaza, regardless of whether that is where they are from, as part of a two-state solution that gives both Palestinians and Jews a country of their own. But with every passing year, as Israel further entrenches its control over all the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterannean Sea, this supposedly realistic alternative grows more detached from reality. There will be no viable, sovereign, Palestinian state to which refugees can go. What remains of the case against Palestinian refugee return is a series of historical and legal arguments, peddled by Israeli and American Jewish leaders, about why Palestinians deserved their expulsion and have no right to remedy it now. These arguments are not only unconvincing but deeply ironic, since they ask Palestinians to repudiate the very principles of intergenerational memory and historical restitution that Jews hold sacred. If Palestinians have no right to return to their homeland, neither do we.

The consequences of these efforts to rationalize and bury the Nakba are not theoretical. They are playing themselves out right now on the streets of Sheikh Jarrah. The Israeli leaders who justify expelling Palestinians today in order to make Jerusalem a Jewish city are merely paraphrasing the Jewish organizations that have spent the last several decades justifying the expulsion of Palestinians in 1948 in order to create a Jewish state. What Ta-Nehisi Coates has observed about the United States, and Desmond Tutu has observed about South Africa—that historical crimes that go unaddressed generally reappear, in different guise—is true for Israel-Palestine as well. Refugee return therefore constitutes more than mere repentance for the past. It is a prerequisite for building a future in which both Jews and Palestinians enjoy safety and freedom in the land each people calls home.

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST REFUGEE RETURN begins with a series of myths about what happened in 1948, which allow Israeli and American Jewish leaders to claim that Palestinians effectively expelled themselves.

The most enduring myth is that Palestinians fled because Arab and Palestinian officials told them to. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) asserts that many Palestinians left “at the urging of Arab leaders, and expected to return after a quick and certain Arab victory over the new Jewish state.” The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi debunked this claim as early as 1959. In a study of Arab radio broadcasts and newspapers, and the communiques of the Arab League and various Arab and Palestinian fighting forces, he revealed that, far from urging Palestinians to leave, Palestinian and Arab officials often pleaded with them to stay. Decades later, employing primarily Israeli and British archives for his book, The Birth of the Refugee Problem Revisited, the Israeli historian Benny Morris did uncover evidence of Arab leaders urging women, children, and the elderly to evacuate villages so Arab fighters could better defend them. Still, he concluded that what Arab leaders did “to promote or stifle the exodus was only of secondary importance.” It was Zionist military operations that proved “the major precipitants to flight.” Zionist leaders at the time offered a similar assessment. Israel’s intelligence service noted in a June 1948 report that the “impact of ‘Jewish military action’ . . . on the migration was decisive.” It added that “orders and directives issued by Arab institutions and gangs” accounted for the evacuation of only 5% of villages.

The Jewish establishment’s narrative of Palestinian self-dispossession also blames Arab governments for rejecting the United Nations proposal to partition Mandatory Palestine. “Zionist leaders accepted the partition plan despite its less-than-ideal solution,” the ADL has argued. “It was the Arab nations who refused . . . Had the Arabs accepted the plan in 1947 there would today be an Arab state alongside the Jewish State of Israel and the heartache and bloodshed that have characterized the Arab-Israeli conflict would have been avoided.”

This is misleading. Zionist leaders accepted the UN partition plan on paper while undoing it on the ground. The UN proposal envisioned a Jewish state encompassing 55% of Mandatory Palestine’s land even though Jews composed only a third of its population. Within the new state’s suggested borders, Palestinians thus constituted as much as 47% of the population. Most Zionist leaders considered this unacceptable. Morris notes that David Ben-Gurion, soon to be Israel’s first prime minister, “clearly wanted as few Arabs as possible in the Jewish State.” As early as 1938, he had declared, “I support compulsory transfer.” Ben-Gurion’s logic, concludes Morris, was clear: “without some sort of massive displacement of Arabs from the area of the Jewish state-to-be, there could be no viable ‘Jewish’ state.”

Establishment Jewish organizations often link Arab rejection of the UN partition plan to the war that Arab armies waged against Israel. And it is true that, even before the Arab governments officially declared war in May 1948, Arab and Palestinian militias fought the embryonic Jewish state. In February and March of 1948, these forces even came close to cutting off Jewish supply routes to West Jerusalem and other areas of Jewish settlement. Arab forces also committed atrocities. After members of the right-wing Zionist militia, Etzel, threw grenades into a Palestinian crowd near an oil refinery in Haifa in December 1947, the crowd turned on nearby Jewish workers, killing 39 of them. In April of 1948, after Zionist forces killed more than 100 unarmed Palestinians in the village of Deir Yassin, Palestinian militiamen burned dozens of Jewish civilians to death in buses on the road to Jerusalem. In May of that year, Arab fighters vowing revenge for Deir Yassin killed 129 members of the kibbutz of Kfar Etzion, even though they were flying white flags.

But what the establishment Jewish narrative omits is that the vast majority of Palestinians forced from their homes committed no violence at all. In Army of Shadows, Hebrew University historian Hillel Cohen notes that, “Most of the Palestinian Arabs who took up arms were organized in units that defended their villages and homes, or sometimes a group of villages.” They ventured beyond them “only in extremely rare cases.” He adds that, frequently, “local Arab representatives had approached their Jewish neighbors with requests to conclude nonaggression pacts.” When such efforts failed, Palestinian villages and towns often surrendered in the face of Zionist might. In most cases, their residents were expelled anyway. Their presence was intolerable not because they had personally threatened Jews but because they threatened the demography of a Jewish state.

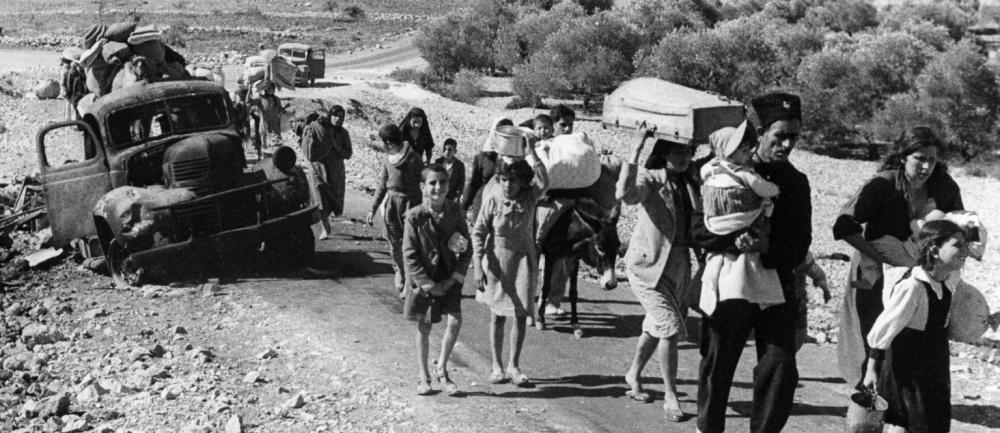

IN FOCUSING ON THE BEHAVIOR of Arab leaders, the Jewish establishment tends to distract from what the Nakba meant for ordinary people. Perhaps that is intentional, because the more one confronts the Nakba’s human toll, the harder it becomes to rationalize what happened then, and to oppose justice for Palestinian refugees now. In roughly 18 months, Zionist forces evicted upwards of 700,000 individuals, more than half of Mandatory Palestine’s Arab population. They emptied more than 400 Palestinian villages and depopulated the Palestinian sections of many of Israel-Palestine’s mixed cities and towns. In each of these places, Palestinians endured horrors that haunted them for the rest of their lives.

In April 1948, the largest Zionist fighting force, the Haganah, launched Operation Bi’ur Hametz (Passover Cleaning), which aimed to seize the Palestinian neighborhoods of Haifa, whose population had already been demoralized by the flight of local Palestinian elites. A British intelligence officer accused Haganah troops of strafing the harbor with “completely indiscriminate . . . machinegun fire, mortar fire and sniping.” The assault on Arab neighborhoods sparked what one Palestinian observer termed a “mad rush to the port” in which “man trampled on fellow man” in a desperate effort to board boats leaving the city, some of which capsized. Many evacuees sought sanctuary up the coast in Acre. Later that month, the Haganah launched mortar attacks on that city, too. It also cut off Acre’s supply of water and electricity, which likely contributed to a typhoid outbreak, thus hastening the population’s flight.

In October of that year, Israeli troops entered the largely Catholic and Greek Orthodox village of Eilaboun in the Galilee. According to the Palestinian filmmaker Hisham Zreiq, who used oral histories, Israeli documents, and a UN observer report to reconstruct events, the troops were met by priests holding a white flag. Soldiers from the Golani Brigade responded by assembling villagers in the town square. They forced the bulk of Eliaboun’s residents to evacuate the village and head north, thus serving as human shields for Israeli forces who trailed behind them, in case the road was mined. After forcing the villagers to walk all day with little food or water, the soldiers robbed them of their valuables and loaded them on trucks that deposited them across the Lebanese border. According to an eyewitness, the roughly dozen men held back in the town square were executed in groups of three.

In al-Dawayima, in the Hebron hills, where Israeli forces reportedly killed between 80 and 100 men, women, and children—and, in one instance, forced an elderly woman into a house and then blew it up—an Israeli soldier told an Israeli journalist that “cultured, polite commanders” behaved like “base murderers.” After Israeli troops evicted as many as 70,000 Palestinians from Lydda and Ramle in July, an Israeli intelligence officer analogized the event to a “pogrom” or the Roman “exile of Israel.” Less openly discussed were the rapes by Zionist soldiers. In The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Morris recorded “several dozen cases”—but later acknowledged that since such incidents generally went unreported, that figure was probably “just the tip of the iceberg.”

Even survivors who avoided permanent physical injury were never the same. At the age of seven, Fawaz Turki fled Haifa with his family on foot. Decades later he wrote about “the apocalyptic images that my mind would dredge up, out of nowhere, of our refugee exodus . . . where pregnant women gave birth on the wayside, screaming to heaven with labour pain, and where children walked alone, with no hands to hold.” Nazmiyya al-Kilani walked with a broken leg, one child in her arms and another tied to her apron, to the Haifa port, where she boarded a boat to Acre. In the chaos she lost contact with her husband, father, brother, and sisters, all of whom were deported from the country. For the next half-century, until her adult daughter tracked down her siblings in Syria, she did not know if they were alive or dead. According to Elias Srouji, forced to march from his Galilean village to the Lebanese border, “The most heartrending sight was the cats and dogs, barking and carrying on, trying to follow their masters. I heard a man shout to his dog: ‘Go back! At least you can stay!’” (Jews familiar with the way our sacred texts imagine expulsion may hear a faint echo. The Talmud records that when the First Temple was destroyed, “even the animals and birds were exiled.”)

Eviction was generally followed by theft. In June 1948, Ben-Gurion himself lamented the “mass plunder to which all sectors of the country’s Jewish community were party.” In Tiberias, according to an official from the Jewish National Fund (JNF), Haganah troops “came in cars and boats and loaded all sorts of goods [such as] refrigerators beds” while groups of Jewish civilians “walked about pillaging from the Arab houses and shops.” In Deir Yassin, an officer from the elite Haganah unit, the Palmach, observed that fighters from the right-wing Zionist militia Lechi were “going about the village robbing and stealing everything: Chickens, radio sets, sugar, money, gold and more.” When the Haganah cleared the village of Sheikh Badr in West Jerusalem, according to Morris, Jews from the nearby neighborhood of Nachlaot “descended on Sheikh Badr and pillaged it.” Haganah troops fired in the air to disperse the mob, and British police later tried to protect vacated Palestinian houses. But once both forces left, Nachlaot residents returned, “torching and pillaging what remained.”

Jewish authorities soon systematized the plunder. In July 1948, Israel created a “Custodian for Deserted Property,” which it empowered to distribute houses, lands, and other valuables that refugees had left behind. Kibbutz officials, notes the historian Alon Confino, “clamored for Arab land,” and the Israeli government leased much of it to them in September, using the Jewish National Fund as a middleman. Atop other former Palestinian villages, the JNF created national parks. In urban areas, it distributed Palestinian houses to new Jewish immigrants. Israel’s national library took possession of roughly 30,000 books stolen from Palestinian homes. Many remain there today.

In November 1948, Israel conducted a census. A month later, the Knesset passed the Law for the Property of Absentees, which determined that anyone not residing on their property during the census forfeited their right to it. This meant not only that Palestinians outside Israel’s borders were barred from reclaiming their houses and lands, but that even Palestinians displaced inside Israel, who became Israeli citizens, generally lost their property to the state. In a phrase worthy of Orwell, the Israeli government dubbed them “present absentees.”

The scale of the land theft was astonishing. When the United Nations passed its partition plan in November 1947, Jews owned roughly 7% of the territory of Mandatory Palestine. By the early 1950s, almost 95% of Israel’s land was owned by the Jewish state.

SINCE IT TOOK the expulsion of Palestinians to create a viable Jewish state, many Jews fear—with good reason—that acknowledging and rectifying that expulsion would challenge Jewish statehood itself. This fear is often stated in numerical terms: If too many Palestinian refugees return, Jews might no longer constitute a majority. But the anxiety goes deeper. Why do so few Jewish institutions teach about the Nakba? Because it is hard to look the Nakba in the eye and not wonder, at least furtively, about the ethics of creating a Jewish state when doing so required forcing vast numbers of Palestinians from their homes. Why do so few Jewish institutions try to envision return? Because doing so butts up against pillars of Jewish statehood: for instance, the fact that the Israel Land Council, which controls 93% of the land inside Israel’s original boundaries, reserves almost half of its seats for representatives of the Jewish National Fund, which defines itself as “a trustee on behalf of the Jewish People.” Envisioning return requires uprooting deeply entrenched structures of Jewish supremacy and Palestinian subordination. It requires envisioning a different kind of country.

I have argued previously that Jews could not only survive, but thrive, in a country that replaces Jewish privilege with equality under the law. A wealth of comparative data suggests that political systems that give everyone a voice in government generally prove more stable and more peaceful for everyone. But, even in the best of circumstances, such a transformation would be profoundly jarring to many Jews. It would require redistributing land, economic resources, and political power, and perhaps just as painfully, reconsidering cherished myths about the Israeli and Zionist past. At this juncture in history, it is impossible to know how so fundamental a transition might occur, or if it ever will.

To ensure that this reckoning never comes, the Israeli government and its American Jewish allies have offered a range of legal, historical, and logistical arguments against refugee return. These all share one thing in common: Were they applied to any group other than Palestinians, American Jewish leaders would likely dismiss them as immoral and absurd.

Consider the claim that Palestinian refugees have no right to return under international law. On its face, this makes little sense. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, passed in 1948 and reaffirmed more than a hundred times since, addresses Palestinian refugees specifically. It asserts that those “wishing to return to their homes and to live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.”

Opponents of Palestinian return have rejoinders to these documents. They argue that General Assembly Resolutions aren’t legally binding. They claim that since Israel was only created in May 1948, and Palestinian refugees were never its citizens, they would not be returning to “their country.” But these are legalisms devoid of moral content. In the decades since World War II, the international bodies that oversee refugees have developed a clear ethical principle: People who want to return home should be allowed to do so. Although the pace of repatriation has slowed in recent years, since 1990 almost nine times as many refugees have returned to their home countries as have been resettled in new ones. And as a 2019 report by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) explains, resettlement is preferred only when a refugee’s home country is so dangerous that it “cannot provide them with appropriate protection and support.”

When the refugees aren’t Palestinian, Jewish leaders don’t merely accept this principle, they champion it. The 1995 Dayton Agreement, which ended years of warfare between Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia, states: “All refugees and displaced persons have the right freely to return to their homes of origin” and “to have restored to them property of which they were deprived in the course of hostilities.” The American Jewish Committee—whose CEO, David Harris, has demanded that Palestinian refugees begin “anew” in “adopted lands”—not only endorsed the Dayton agreement but urged that it be enforced with US troops. In 2019, AIPAC applauded Congress for imposing sanctions aimed at forcing the Syrian government to, among other things, permit “the safe, voluntary, and dignified return of Syrians displaced by the conflict.” That same year, the Union for Reform Judaism, in justifying its support for reparations for Black Americans, approvingly cited a UN resolution that defines reparations as including the right to “return to one’s place of residence.”

Jewish leaders also endorse the rights of return and compensation for Jews expelled from Arab lands. In 2013, World Jewish Congress President Ronald Lauder claimed, “The world has long recognized the Palestinian refugee problem, but without recognizing the other side of the story—the 850,000 Jewish refugees of Arab countries.” Arab Jews, he argued, deserve “equal rights and treatment under international law.”

Given that international law strongly favors refugee return, the logical implication of Lauder’s words is that Arab Jews should be allowed to go back to their ancestral countries. But, of course, Lauder and other Jewish leaders don’t want that; a Jewish exodus from Israel would undermine the rationale for a Jewish state. What they want is for the world to recognize Arab Jewish refugees’ rights to repatriation and compensation so Israel can trade away those rights in return for Palestinian refugees relinquishing theirs. As McGill University political scientist Rex Brynen has noted, during the Oslo peace process Israeli negotiators privately acknowledged that they were using the flight of Arab Jews as “a bargaining chip, intended to counterweigh Palestinian claims.” In so doing, Israeli leaders backhandedly conceded the legitimacy of the very rights they don’t want Palestinians to have.

The double standard that suffuses establishment Jewish arguments against the Palestinian right of return expresses itself most glaringly in the debate over who counts as a refugee. Jewish leaders often claim that only Palestinians who were themselves expelled deserve the designation, not their descendants. It’s a cynical argument: Later generations of Palestinians would not need refugee status had Israel allowed their expelled parents or grandparents to return. It’s hypocritical too. Distinguishing between expelled Palestinians and their descendants allows Jewish leaders to cloak their opposition in the language of universal principle—“refugee status should not be handed down”—while in reality, they don’t adhere to this principle universally. Across the globe, refugee designations are frequently handed down from one generation to the next, yet Jewish organizations do not object. As UNRWA has noted, “Palestine refugees are not distinct from other protracted refugee situations such as those from Afghanistan or Somalia, where there are multiple generations of refugees.”

Moreover, the same American Jewish leaders who decry multigenerational refugee status when it applies to Palestinians celebrate it when it applies to Jews. In 2018, AJC CEO David Harris expressed outrage that UNRWA’s mandate “covers all descendants, without limit, of those deemed refugees in 1948.” The following year, Harris—who was born in the United States to a refugee father who grew up in Vienna—announced that he had taken Austrian citizenship “in honor and memory of my father.” In 2016, after Spain and Portugal offered citizenship to roughly 10,000 descendants of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula more than 500 years ago, the AJC’s Associate Executive Director declared, “We stand in awe at the commitment and efforts undertaken both by Portugal and Spain to come to terms with their past.”

NOT ONLY do Jewish leaders insist that Israel has no legal or historical obligation to repatriate or compensate Palestinians; they also claim that doing so is impossible. Israel, the ADL notes, believes that “‘return’ is not viable for such a small state.” Veteran Republican foreign policy official Elliott Abrams has called compensating all Palestinian refugees a “fantasy.” Too much time has passed, too many Palestinian homes have been destroyed, there are too many refugees. It is not possible to remedy the past. The irony is that when it comes to compensation for historical crimes, Jewish organizations have shown just how possible it is to overcome these logistical hurdles. And when it comes to effectively resettling large numbers of people in a short time in a small space, Israel leads the world.

More than 50 years after the Holocaust, Jewish organizations negotiated an agreement in which Swiss banks paid more than $1 billion to reimburse Jews whose accounts they had expropriated during World War II. In 2018, the World Jewish Restitution Organization welcomed new US legislation to help Holocaust survivors and their descendants reclaim property in Poland. While the Holocaust, unlike the Nakba, saw millions murdered, the Jewish groups in these cases were not seeking compensation for murder. They were seeking compensation for theft. If Jews robbed en masse in the 1940s deserve reparations, surely Palestinians do too.

When Jewish organizations deem it morally necessary, they find ways to determine the value of lost property. So does the Israeli government, which estimated the value of property lost by Jewish settlers withdrawn from the Gaza Strip in order to compensate them. Such calculations can be made for property lost in the Nakba as well. UN Resolution 194, which declared that Palestinian refugees were entitled to compensation “for loss of, or damage to, property,” created the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) to tally the losses. Using land registers, tax records, and other documents from the British mandate, the UNCCP between 1953 and 1964 assembled what Randolph-Macon College historian Michael Fischbach has called “one of the most complete sets of records documenting the landholdings of any group of refugees in the twentieth century.” In recent decades, those records have been turned into a searchable database and cross-referenced with information from the Israeli Land Registry. The primary barrier to compensating Palestinian refugees is not technical complexity. It’s political will.

The same goes for allowing Palestinian refugees to return home. Lubnah Shomali of the Badil Resource Center, which promotes Palestinian refugee rights, has noted that, “If any state is an expert in receiving masses and masses of people and settling them in a very small territory, it’s Israel.” In its first four years of existence, Israel—which in 1948 contained just over 800,000 citizens—absorbed close to 700,000 immigrants. At the height of the Soviet exodus in the early 1990s, when the Jewish state totaled roughly 5 million citizens, alongside several million Palestinian non-citizens in the West Bank and Gaza, it took in another 500,000 immigrants over four years. The number of returning Palestinian refugees could be substantially higher than that, or not. It’s impossible to predict. But this much is clear: If millions of diaspora Jews suddenly launched a vast new aliyah to Israel, Jewish leaders would not say that Israel lacked the capacity to absorb them. To the contrary, Israel would exercise the capability it displayed in the late 1940s and early 1990s, when, as Technion urban planning professor Rachelle Alterman has detailed, it quickly built large amounts of housing to accommodate new immigrants.

Palestinian scholars have begun imagining what might be required to absorb Palestinian refugees who want to return. One option would be to build where former Palestinian villages once stood since, according to Shomali, roughly 70% of those depopulated and destroyed in 1948 remain vacant. In many cases, the rural land on which they sat now constitutes nature preserves or military zones. The Palestinian geographer Salman Abu Sitta imagines a Palestinian Lands Authority, which could dole out plots in former villages to the families of those who lived there. He envisions many returnees “resuming their traditional occupation in agriculture, with more investment and advanced technology.” He’s even convened contests in which Palestinian architecture students build models of restored villages.

The Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi, by contrast, told me he thought it unlikely that many refugees—most of whom now live in or near cities—would return to farming. Most would probably prefer to live in urban areas. For Palestinians uninterested in reconstituting destroyed rural villages, Badil has partnered with Zochrot, an Israeli organization that raises awareness about the Nakba, to suggest two other options, both of which bear some resemblance to Israel’s strategy for settling Soviet immigrants in the 1990s. In that case, the government gave newcomers money for rent while also offering developers subsidies to rapidly build affordable homes. Now, Badil and Zochrot are suggesting a “fast track” in which refugees would be granted citizenship and a sum of money and then left to find housing on their own, or a slower track that would require refugees to wait as the government oversaw the construction of housing designated for them near urban areas with available jobs.

When Jews imagine Palestinian refugee return, most probably don’t imagine a modified version of Israel’s absorption of Soviet Jews. More likely, they imagine Palestinians expelling Jews from their homes. Given Jewish history, and the trauma that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has inflicted on both sides, these fears are understandable. But there is little evidence that they reflect reality. For starters, not many Israeli Jews live in former Palestinian homes since, tragically, only a few thousand remain. More importantly, the Palestinian intellectuals and activists who envision return generally insist that significant forced expulsion of Jews is neither necessary nor desirable. Abu Sitta argues, “it is possible to implement the return of the refugees without major displacement to the occupants of their houses.” Yusuf Jabarin, a Palestinian professor of geography who has developed plans for rebuilding destroyed villages, emphasizes, “I have no interest in building my life on the basis of attacks on Jews and making them fear they have no place here.” Asked about Jews living in formerly Palestinian homes, Edward Said in 2000 declared that “some humane and moderate solution should be found where the claims of the present and the claims of the past are addressed . . . I’m totally against eviction.”

Badil and Zochrot have outlined what a “humane and moderate solution” might look like. If a Jewish family owns a home once owned by a Palestinian, first the original Palestinian owner (or their heirs) and then the current Jewish owner would be offered the cash value of the home in return for relinquishing their claim. If neither accepted the payment, Zochrot activists Noa Levy and Eitan Bronstein Aparicio have suggested a further compromise: Ownership of the property would revert to the original Palestinian owners, but the Jewish occupants would continue living there. The Palestinian owners would receive compensation until the Jewish occupants moved or died, at which point they would regain possession. In cases where Jewish institutions sit where Palestinian homes once stood—for instance, Tel Aviv University, which was built on the site of the destroyed village of al-Shaykh Muwannis—Zochrot has proposed that the Jewish inhabitants pay the former owners for the use of the land.

EFFORTS TO FACE AND REDRESS HISTORIC WRONGS are rarely simple, rapid, uncontested, or complete. Seventeen years after the end of apartheid, the South African government in March unveiled a special court to fast-track the redistribution of land stolen from Black South Africans; some white farmers worry it could threaten their livelihood. In Canada, where the acknowledgement of native lands has become standard practice at public events, including hockey games, some conservative politicians are pushing back. So are some Indigenous leaders, who claim the practice has become meaningless. Thousands of US schools now use The New York Times’s 1619 curriculum, which aims to make slavery and white supremacy central to the way American history is taught. Meanwhile, some Republican legislators are trying to ban it.

But as fraught and imperfect as efforts at historical justice can be, it is worth considering what happens when they do not occur. There is a reason that the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates ends his famous essay on reparations for slavery with the subprime mortgage crisis that bankrupted many Black Americans in the first decade of the 21st century, and that the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama—best known for memorializing lynchings—ends its main exhibit with the current crisis of mass incarceration. The crimes of the past, when left unaddressed, do not remain in the past.

That’s true for the Nakba as well. Israel did not stop expelling Palestinians when its war for independence ended. It displaced close to 400,000 more Palestinians when it conquered the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967—roughly a quarter of whom only lived in the West Bank or Gaza because their families had fled there, as refugees, in 1948. Between 1967 and 1994, Israel rid itself of another 250,000 Palestinians through a policy that revoked the residencies of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza who left the territories for an extended period of time. Since 2006, according to Badil, almost 10,000 Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem have watched the Israeli government demolish their homes. In the 1950s, 28 Palestinian families forced from Jaffa and Haifa in 1948 relocated to the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. After a decades-long campaign by Jewish settlers, the Jerusalem District Court ruled earlier this month that six of them should be evicted. By refusing to acknowledge the Nakba, the Israeli government prepared the ground for its perpetuation. And by refusing to forget the Nakba, Palestinians—and some dissident Israeli Jews—prepared the ground for the resistance that is now convulsing Jerusalem, and Israel-Palestine as a whole.

“We are what we remember,” wrote the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. “As with an individual suffering from dementia, so with a culture as a whole: the loss of memory is experienced as a loss of identity.” For a stateless people, collective memory is key to national survival. That’s why for centuries diaspora Jews asked to be buried with soil from the land of Israel. And it’s why Palestinians gather soil from the villages from which their parents or grandparents were expelled. For Jews to tell Palestinians that peace requires them to forget the Nakba is grotesque. In our bones, Jews know that when you tell a people to forget its past you are not proposing peace. You are proposing extinction.

Conversely, honestly facing the past—a process Desmond Tutu has likened to “opening wounds” and “cleansing them so that they do not fester”—can provide the basis for genuine reconciliation. In 1977, Palestinian American graduate student George Bisharat traveled to the West Jerusalem neighborhood of Talbiyeh and knocked on the door of the house his grandfather had built and been robbed of. The elderly woman who answered the door told him his family had never lived there. “The humiliation of having to plead to enter my family’s home . . . burned inside me,” Bisharat later wrote. In 2000, by then a law professor, he returned with his family. As his wife and children looked on, a man originally from New York answered the door and told him the same thing: It was not his family’s home.

But after Bisharat chronicled his experiences, he received an invitation from a former soldier who had briefly lived in the house after the Haganah seized it in 1948. When they met, the man said, “I am sorry, I was blind. What we did was wrong,” and then added, “I owe your family three month’s rent.” In that moment, Bisharat wrote, he experienced “an untapped reservoir of Palestinian magnanimity and good will that could transform the relations between the two peoples, and make things possible that are not possible today.”

There is a Hebrew word for the behavior of that former Haganah soldier: Teshuvah, which is generally translated as “repentance.” Ironically enough, however, its literal definition is “return.” In Jewish tradition, return need not be physical; it can also be ethical and spiritual. Which means that the return of Palestinian refugees—far from necessitating Jewish exile—could be a kind of return for us as well, a return to traditions of memory and justice that the Nakba has evicted from organized Jewish life. “The occupier and myself—both of us suffer from exile,” Mahmoud Darwish once declared. “He is an exile in me and I am the victim of his exile.” The longer the Nakba continues, the deeper this Jewish moral exile becomes. By facing it squarely and beginning a process of repair, both Jews and Palestinians, in different ways, can start to come home.

Eliot Cohen, Sam Sussman, and Jonah Karsh assisted with the research for this essay.

[Peter Beinart is editor-at-large of Jewish Currents.]