Confronting the Myth of Objectivity

Sometimes, after educating teachers about the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, after dealing with racist incidents in the classroom, after spending hours talking about slaughter and mass graves, Karlos Hill weeps as he drives home. “When I talk about sobbing, it’s because of the emotional toll of doing the work. It just sort of drains you,” he told me.

But when I ask him to talk more about this toll, the chair of the African and African American Studies Department at the University of Oklahoma changes the topic. He’d rather discuss the joys of his profession: “I wake up every day, even when I’m tired, with a deep sense of purpose and deep sense of mission.”

I called Hill on a quiet Saturday in late April, a rare day when he had some time in his impossibly busy schedule. As the centenary of the Tulsa massacre approaches, he wants to talk not only about his research and teaching on the subject but also about the obligation of historians to work for social change.

Hill came to my attention through his essay, “Community-Engaged History: A Reflection on the 100th Anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre,” forthcoming in the American Historical Review. It’s the most personal article I’ve ever read in an elite academic publication. Hill deploys his experiences in Tulsa teaching the history of the massacre to confront the myth of objectivity. For the last three years, Hill has been the cocreator and coleader of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Teachers’ Institute, which trains K-12 teachers to inform students and dispel the bad history that too many have learned.

An armed white man in overalls looks at the camera. The back of the photograph contains a handwritten notation stating, "Proud of his pilfering. Race pride far astray." (Tulsa Historical Society)

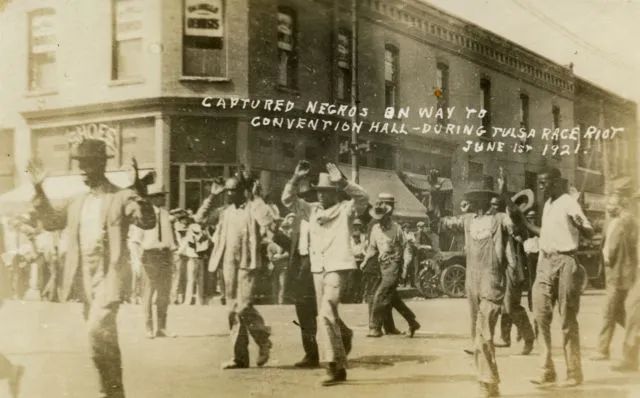

The facts of the massacre are, of course, important: The violence began on May 31, 1921, when a white mob gathered outside the county courthouse, set on lynching a Black man named Dick Rowland, whom a local newspaper had accused of attacking a 17-year-old white woman. Two groups of Black men arrived to guard the courthouse. Hill’s article describes what ensued when “a white bystander moved to disarm one of the black men. As the two men struggled, one of their guns went off. In the ensuing chaos, some men among the white crowd began shooting indiscriminately at the retreating black men, and some of the blacks returned fire. Twenty people were killed or wounded in that brief initial episode. It was the opening salvo of the worst race massacre in American history.” Over the next half-day, thousands of white Oklahomans descended on the Greenwood District to murder, loot, and burn down the prosperous neighborhood known as Black Wall Street. Police and national guard detained at least 4,000 Black residents and zero white residents. To this day, no one knows for sure how many Black Tulsans were killed or where their bodies are buried. Last October, archaeologists identified a mass grave with at least 10 coffins.

But the facts alone aren’t enough. Until recently, despite the magnitude of the violence, Hill told me that the massacre was little known in the United States, and when it was taught at all, teachers typically characterized it as a “riot.” Correcting that requires not just a more accurate scholarly narrative but also helping others tell a better story. His teaching experiences, which have not always been easy, led him to open his new essay by saying, “In the twenty-first century, a historian’s power lies in being a catalyst for social change.”

He told me that he’s “trying to nudge historians to think more deeply about what their commitments are, what their research is, and how it maybe connects to what’s happening, not just around the nation, but in their own community.” He contended that as scholars, “our power, our capacity to impact people and institutions and culture lies in the extent to which we are willing to align our talents, our abilities, our gifts with community struggles and issues.”

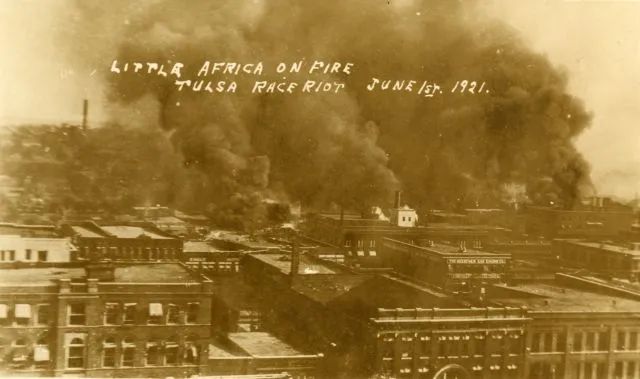

Photo caption reads, "Little Africa on fire, Tulsa Race Riot, June 1, 1921." (Tulsa Historical Society)

By encouraging academics to deliberately effect change, Hill is placing himself on one side of a long-standing debate about the nature of history. He is arguing against a still large contingent of the discipline who say that historians should be dispassionate and strive toward objectivity. Let the sources do the work, they say, and keep politics and activism out of it. Hill, on the other hand, argues that historians can “do legitimate scholarship that advances the field while simultaneously engaging our communities.”

History, of course, is not the only field where these debates play out. Journalism has been wracked with debates about objectivity for decades. Science also faces a reckoning over the way that that pretending all inquiry is value-neutral promotes harm. In all cases, the discourse revolves around questions of race, gender, and other forms of identity, as well as the question of who sets the parameters for making knowledge. In his article, Hill points to a recent debate published in the same journal around Native American and Indigenous Studies, in which one non-Native professor “expressed deep skepticism about capacity to center scholarship on the communities of which they are a part and/or which they desire to serve while simultaneously doing history objectively, performing ‘cold’ readings of historical documents.” But if scholars can’t support marginalized communities, what is their research even for? Why is being a “cold” reader a virtue? And will that even result in better analysis or understanding?

When I asked Hill about his argument about the role of historians, he admitted to being intentionally provocative. But he said, “I’ve just come to understand, that my value to my community is my ability to align my research, my writing, my teaching with community struggles, community initiatives, justice work that’s happening.” He acknowledged that not every historian will be studying the history of a place or people where they live, but he told me that his piece is “really about trying to nudge historians to think more deeply about what their commitments are, what their research is, and how it maybe perhaps connects to what’s happening in their own community.”

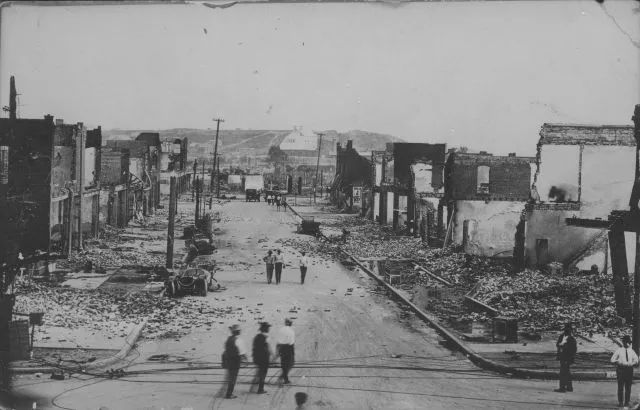

A photograph looking north along North Greenwood Avenue following the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. (Tulsa Historical Society)

Hill’s own decision to rethink the work of history came in a mid-career moment. He received his PhD from the University of Illinois in 2009, and took a tenure-track position in the history department at Texas Tech that same year, eventually completing an academic book about anti-lynching movements and narratives from Black Americans. He received tenure, moved to Oklahoma, and found himself a little lost. “In the lead up to getting tenure, I was so focused, and really frightened of not getting tenure that that was my only thought. Just get tenure. Work really hard. Write this book. Write as many articles as you can. And, and hopefully, that’s enough. And so once that force leaves, it’s like, ‘OK, who am I? What am I doing?’” He began to ask himself not “What to write?” but “Who are you writing for? And why are you writing?” He told me that at the time, “I didn’t have answers to those questions.”

In our conversations, it became obvious that he found those answers in serving his community, saying, “I think I found my muse.” In the lead-up to the centenary, he’s devoted himself to the collaborative work commemorating and memorializing the Tulsa race massacre. Teaching teachers is part of it, but he’s also published a photographic history. He told me, “In 2016–17, the default phrasing was ‘race riot.’ The community used that language. It became clear that ‘massacre’ was much more appropriate, and the book to visually represent what that really means, what ‘massacre’ really connotes, to compellingly portray the destruction, the loss of life, but also the rebuilding.”

The challenge of the book, The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre A Photographic History, is that the surviving photographs were taken by white Oklahomans “to tell the story of whites suppressing a negro rebellion, or insurrection.” But Hill said he realized, “If you could pair the photographs of destruction that were taken by whites with oral history testimony, there’s a way that testimony could recontextualize those images and help people profoundly understand the massacre from the point of view of victims, survivors, and descendants.”

A postcard contains the caption, "Captured Negros on Way to Convention Hall - During Tulsa Race Riot June 1st 1921." (Tulsa Historical Society)

But Hill is not just saying that people whose fields fit so neatly into the needs of their community should push for change. I ask him how scholars like me, originally a historian of medieval Venice, might fit into his vision. With a laugh, he replied, “I think scholars are smart enough to figure out the how if they really want to.”

For many, the how emerges in teaching. Hill encourages academics to stop thinking only about scholarship. “Who’s in your classroom?” he asked me. “Whatever you’re teaching, are you teaching it in socially and culturally responsible ways? Or are you putting equity at the center of your classroom?” Every class, he said, offers opportunities to emphasize social justice.

History is always contested ground, but fights over the past have been especially fierce of late—first with conflicts over statues of Robert E. Lee and his fellow Confederate leaders and then with the right-wing backlash to the 1619 Project from The New York Times and the obsession with banning critical race theory (or what conservatives imagine CRT to be, anyway). Taken together, it’s clear that Republican lawmakers are trying to forbid the teaching of structural racism in American history and mandate lessons that reinforce the fiction of a white, Christian, meritocratic America. What we see in the right’s manufactured culture-war controversies is the understanding that the stories we tell shape the futures we can imagine. Hill’s decision to place his expertise, talents, and training in the service of a community in need of access to truer stories couldn’t come at a more consequential moment.

Five Black men salvage bricks from the burned ruins of the Gurley Hotel. (Tulsa Historical Society)

In his essay, Hill writes that Tulsa’s Greenwood District “was built on hope, destroyed by white mob violence and vengeance, and then raised again from the ashes through the strength of black resilience and faith. Buoyed by its powerful past, Greenwood lives on, and with the activities surrounding the approach of the 100th anniversary of the massacre, working toward healing history has taken center stage.”

For Hill, “healing history” requires scholars to amplify suppressed voices and create the conditions for new narratives to propagate in the communities that long to hear them. It’s in working in service of others, Hill argues, that historians can find their power.

Copyright c 2021 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

David M. Perry is a journalist and historian. His website is davidmperry.com.

Your subscription supports The Nation's award-winning reporting. Choose your plan. Cancel anytime