‘Forget the Alamo’ Unravels a Texas History Made of Myths, or Rather, Lies

As a former student of Texas public schools, much of what I remember from Texas history class boils down to this: General López de Santa Anna, of Mexico, was evil incarnate—my old friends and I still marvel at how much this was hammered into our heads—and the Texas Revolution was a fight for liberty against the tyrannical Mexican government. The Battle of the Alamo, where Texian fighters held out for 13 days and then were slaughtered by Mexican forces, has long been a central part of that story. Every Texan has been told to “remember the Alamo.”

It doesn’t look like that will change any time soon. On Monday, Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill creating “The 1836 Project,” designed to “promote patriotic education” about the year Texas seceded from Mexico. In other words, the law will create a committee to ensure that educational materials centering “Texas values” are provided at state landmarks and encouraged in schools. This comes on the heels of the “critical race theory” bill that has passed through the Legislature, which would restrict how teachers can discuss current events and teach history. The American Historical Association has described the bill as “whitewashing American history,” stating: “Its apparent purposes are to intimidate teachers and stifle independent inquiry and critical thought among students.”

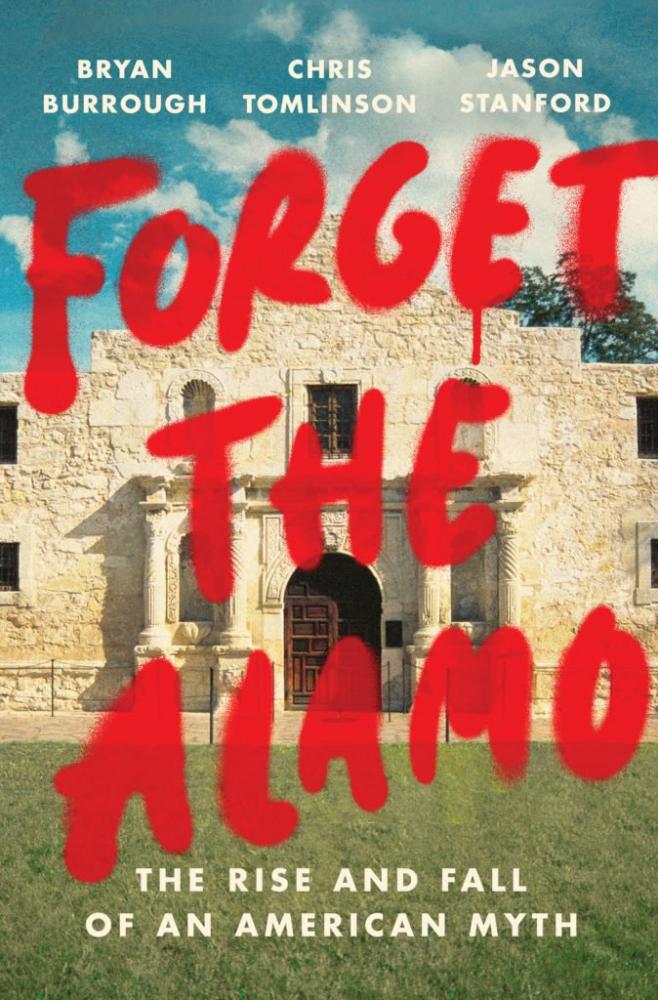

Nevertheless, a new book co-authored by three Texas writers, Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford, urges us to reconsider the Alamo, a symbol we’ve been taught to fiercely and uncritically remember. The authors are aware that their book sounds like a desecration. Starting with the cover of Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of An American Myth, out this week from Penguin Press, the authors lean into associations of defacement with the title scrawled in what looks like red spray paint across an image of the old mission.

Written for popular audiences, the book challenges what the authors refer to as the “Heroic Anglo Narrative.” The traditional telling, which Texas public schools are still required to teach, glorifies the nearly 200 men who came to fight in an insurrection against Mexico in 1836. The devastation at the Alamo turned those men into martyrs leaving behind the prevailing story that they died for liberty and justice. Yet the authors of Forget the Alamo argue that the entire Texas Revolt—“which wasn’t really a revolt at all”—had more to do with protecting slavery from Mexico’s abolitionist government. As they explain it, and as Chicano writers, activists, and communities have long agreed, the events that occurred at the Alamo have been mythologized and used to demonize Mexicans in Texas history and obscure the role of slavery.

Taking a comprehensive look at how the mythos of the Alamo has been molded, Burrough, Tomlinson, and Stanford paint a picture of American slaveholders’ racism as it made its way into Texas. In their stories of these early days, they peel back the facade of the holy trinity of Alamo figures: Jim Bowie, William Barret Travis, and Davy Crockett. All three died at the Alamo and their surnames are memorialized on schools, streets, buildings, and even entire counties. They pull no punches describing Bowie as a “murderer, slaver, and con man;” Travis as “a pompous, racist agitator;” and Crockett as a “self-promoting old fool.”

In the nearly 200 years that followed the battle, we learn about the mechanics of how false histories were reinforced by patriotic white scholars and zealous legislators, including the “Second Battle of the Alamo,” when a Tejana schoolteacher fought to preserve a significant area of the compound. Ultimately she was silenced by the moneyed white elite in San Antonio who sought to transform it into a flashy park instead, and the authors suggest that this moment “represented the victory of mythmaking over historical accuracy.”

Well into the 20th century, it was rare that critical studies of the Alamo were taken seriously, although Latinx writers in the 1920s and Chicano activists in the 1960s wrote their own accounts of Tejano history. Starting in the middle of the century, Hollywood further cemented the profoundly conservative folklore through mass entertainment: In 1948, Walt Disney, fed up with left-leaning labor unions, made a television series on Davy Crockett to encourage “traditional” American values like patriotism, courage, self-sufficiency, and individual liberty, the authors write. John Wayne, a rabid anti-Communist, had similar motivations behind his vision for the film The Alamo, in 1960. Meant to draw parallels with the Soviet Union, Wayne’s characterization of Santa Anna was intended to portray “a bloodthirsty dictator trying to crush good men fighting for self-determination.”

Burrough, Tomlinson, and Stanford are all white male writers, which raises questions. Will this book be afforded the attention and legitimacy that related works by non-white authors haven’t been? Probably, but it shouldn’t. The authors are transparent about the fact that they are far from the first to present an alternative to the “Heroic Anglo Narrative,” and cite Latinx scholarship and perspectives throughout. “We trace its roots to the oral traditions of the Mexican American community, elements of which have long viewed the Alamo as a symbol of Anglo oppression,” they write early on. They dedicate multiple sections to the Mexican American experience of the Alamo myth, highlighting how widespread it is in the Latino community to experience shame and harassment within their school classrooms for being associated with the “bloody dictator” Santa Anna and being “the bad guys.”

The book is aimed at white readers and toward people who haven’t heard these alternative tellings before, which leads to a slightly more moderated tone, and despite their robust critiques, the authors seem conflicted about how strongly to indict Texas history overall. There’s still so much more to unravel about early Texas, especially for Native Americans, whose histories they rarely delve into: The story of the Alamo before 1800—it was built in 1718 by Spanish missionaries to convert Indigenous people to Christianity—is reduced to about a page. If Forget the Alamo becomes a definitive text of revisionist Texas history, there’s a serious question of whether non-white writers, activists, and scholars will ever get their due. There’s also a question of whether the truth they’ve voiced for generations will prevail: When will it finally be normal within Texas history scholarship to call the whole foundation rotten?

Still, the book provides strong, provocative critiques of U.S. imperialism and colonialism. The writers make clear that even before Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, U.S. presidents and Washington insiders were invested in—and had a hand in—destabilizing the region in the hopes of eventually annexing Texas. Forget the Alamo also turns to LBJ, who once said, “Hell, Vietnam is just like the Alamo,” and suggests that the patriotic, pioneering myth of the Alamo has been used to buttress justifications for war across the globe and to the present.

The myth of the Alamo, as we know it, is a lie. It’s been a part of the lie students have learned in school, and animates the lies peddled by legislation like the 1836 Project and the critical race theory bill. But if you want to truly remember the past, you first have to forget it.

[Nic Yeager is the culture fellow at the Observer and the author of the guidebook 111 Places in Austin That You Must Not Miss.]