Pandemic Aid Programs Spur a Record Drop in Poverty

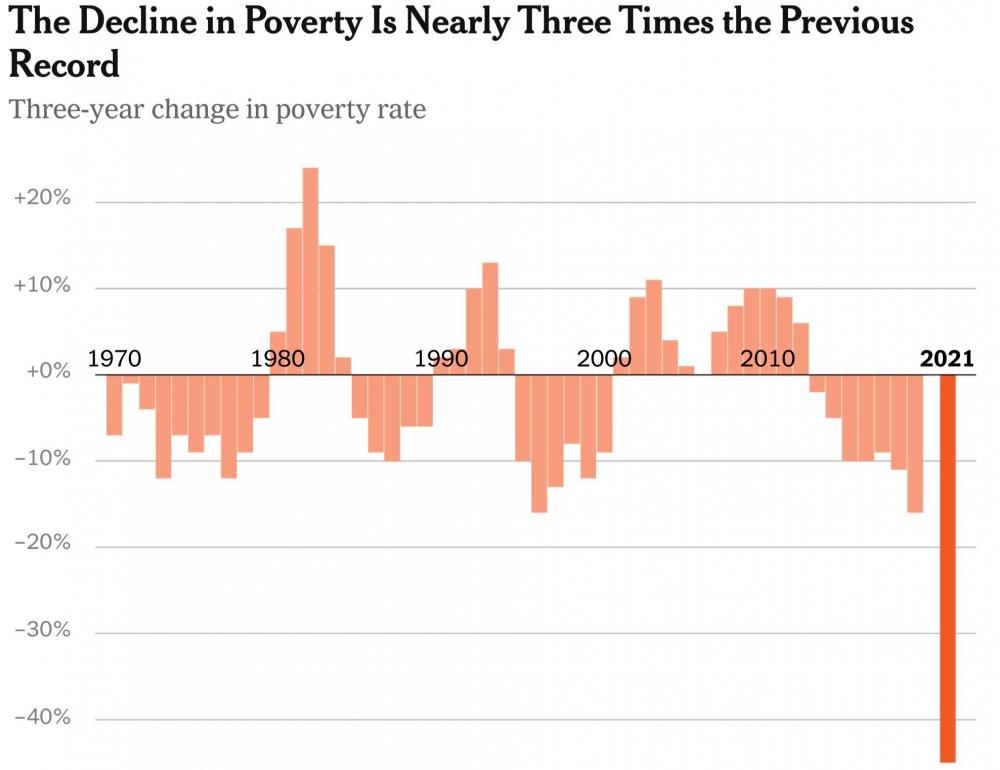

WASHINGTON — The huge increase in government aid prompted by the coronavirus pandemic will cut poverty nearly in half this year from prepandemic levels and push the share of Americans in poverty to the lowest level on record, according to the most comprehensive analysis yet of a vast but temporary expansion of the safety net.

The number of poor Americans is expected to fall by nearly 20 million from 2018 levels, a decline of almost 45 percent. The country has never cut poverty so much in such a short period of time, and the development is especially notable since it defies economic headwinds — the economy has nearly seven million fewer jobs than it did before the pandemic.

The extraordinary reduction in poverty has come at extraordinary cost, with annual spending on major programs projected to rise fourfold to more than $1 trillion. Yet without further expensive new measures, millions of families may find the escape from poverty brief. The three programs that cut poverty most — stimulus checks, increased food stamps and expanded unemployment insurance — have ended or are scheduled to soon revert to their prepandemic size.

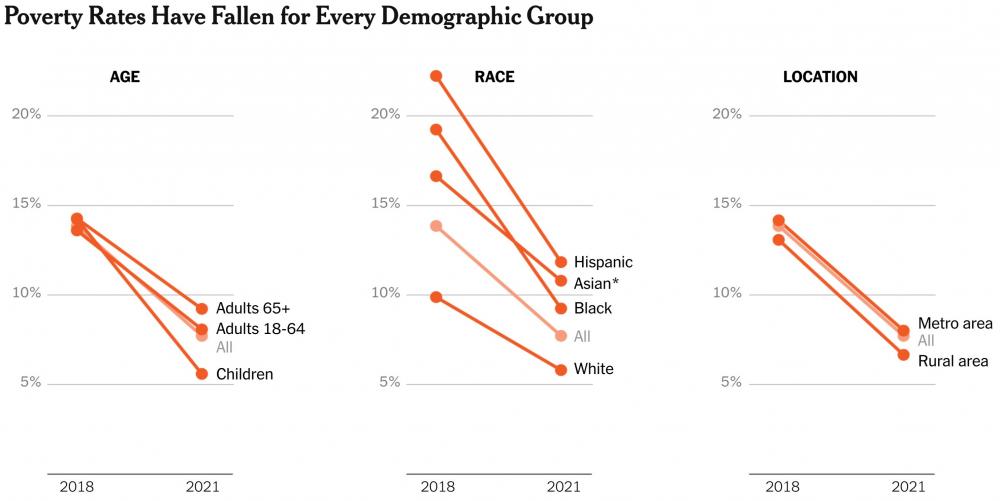

While poverty has fallen most among children, its retreat is remarkably broad: It has dropped among Americans who are white, Black, Latino and Asian, and among Americans of every age group and residents of every state.

Source: The Urban Institute

“These are really large reductions in poverty — the largest short-term reductions we’ve seen,” said Laura Wheaton of the Urban Institute, who produced the estimate with her colleagues Linda Giannarelli and Ilham Dehry. The institute’s simulation model is widely used by government agencies. The New York Times requested the analysis, which expanded on an earlier projection.

The finding — that poverty plunged amid hard times at huge fiscal costs — comes at a moment of sharp debate about the future of the safety net.

The Biden administration has started making monthly payments to most families with children through an expansion of the child tax credit. Democrats want to make the yearlong effort permanent, which would reduce child poverty on a continuing basis by giving their families an income guarantee.

Progressives said the new numbers vindicated their contention that poverty levels reflected political choices and government programs could reduce economic need.

“Wow — these are stunning findings,” said Bob Greenstein, a longtime proponent of safety net programs who is now at the Brookings Institution. “The policy response since the start of the pandemic goes beyond anything we’ve ever done, and the antipoverty effect dwarfs what most of us thought was possible.”

Conservatives say that pandemic-era spending is unsustainable and would harm the poor in the long run, arguing that unconditional aid discourages work and marriage. The child tax credit offers families up to $300 per child a month whether or not parents have jobs, which critics call a return to failed welfare policies.

“There’s no doubt that by shoveling trillions of dollars to the poor, you can reduce poverty,” said Robert Rector of the Heritage Foundation. “But that’s not efficient and it’s not good for the poor because it produces social marginalization. You want policies that encourage work and marriage, not undermine it.”

Poverty rates had reached new lows before the pandemic, Mr. Rector added, under policies meant to discourage welfare and promote work.

To understand how large the recent aid expansion has been, consider the experience of Kathryn Goodwin, a single mother of five in St. Charles, Mo., who managed a group of trailer parks before the pandemic eliminated her $33,000 job.

When she was working, Ms. Goodwin received food stamps, tax credits and aid for a disabled child.

That prepandemic aid raised her income to $52,000 a year.

The local poverty line is about $34,000.

Without the pandemic-era expansions — passed in three rounds under both the Trump and Biden administrations — Ms. Goodwin’s job loss would have caused her income to plunge to about $29,000 (in jobless benefits, food stamps and other aid), leaving her officially poor.

Instead, her income rose above its prepandemic level, though she has not worked for a year. She received about $25,000 in unemployment benefits (about three times what she would have received before the pandemic) and $12,000 in stimulus checks. With increased food stamp benefits and other help, her income grew to $67,000 — almost 30 percent more than when she had a job.

“Without that help, I literally don’t know how I would have survived,” she said. “We would have been homeless.”

Still, Ms. Goodwin, 29, has mixed feelings about large payments with no stipulations.

“In my case, yes, it was very beneficial,” she said. But she said that other people she knew bought big TVs and her former boyfriend bought drugs. “All this free money enabled him to be a worse addict than he already was,” she said. “Why should taxpayers pay for that?”

The Urban Institute’s projections show poverty falling to 7.7 percent this year from 13.9 percent in 2018. That decline, 45 percent, is nearly three times the previous three-year record, according to historical estimates by researchers at Columbia University. The projected drop in child poverty, to 5.6 from 14.2 percent, amounts to a decline of 61 percent. That exceeds the previous 50 years combined, the Columbia figures show.

Sources: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy (analysis of historical data); the Urban Institute (2021 data)

In addition to there being nearly 20 million fewer people in poverty, the institute projects about 10 million fewer in “near poverty,” with incomes of 100 to 150 percent of the poverty line. Under the yardstick the Urban Institute used (the government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure), the poverty line for two adults and two children with typical housing costs is about $30,000.

Sign Up for On Politics With Lisa Lerer A spotlight on the people reshaping our politics. A conversation with voters across the country. And a guiding hand through the endless news cycle, telling you what you really need to know. Get it sent to your inbox.

“The decline in ‘near poverty’ is significant because families in that income range, like people in poverty, suffer high rates of food insecurity and other hardships,” said Elaine Waxman, an Urban Institute researcher.

Poverty fell across racial and ethnic groups but most for people who are Black and Latino, meaning the gap with white Americans narrowed. The Rev. Starsky Wilson, the president of the Children’s Defense Fund, credited the racial protests of the past year for prompting lawmakers to act. “It’s no coincidence that the effort at mobilizing resulted in investments that reduced poverty and narrowed disparities,” he said.

Poverty fell less among Asian Americans, leaving them more likely than Black Americans to be poor. The institute found that was partly because they tended to live in more expensive areas.

Jessica Moore of St. Louis said the expanded aid helped her make a fresh start.

A single mother of three, Ms. Moore, 24, lost work as a banquet server at the pandemic’s start but received enough in unemployment insurance and stimulus checks to buy a car and enroll in community college. She is studying to become an emergency medical technician, which promises to raise her earnings 50 percent.

“When you lose your job, you don’t expect benefits that are more than you were making,” she said. “It was a pure blessing.”

Ms. Goodwin preparing medication for her daughter Aliyah and her son Xavier every morning.

With increased food stamp benefits and other help, the family’s income temporarily grew almost 30 percent even though Ms. Goodwin was not working.

Still, Ms. Goodwin has mixed feelings about large government payments with no stipulations, fearing some people abuse the aid.

Payments also went to people who kept their jobs, which helps explain why “near poverty” fell. The beneficiaries included John Asher of Indianapolis, who once served prison time for selling drugs but is now sober and earning $500 a week as a maintenance man. With $3,200 in stimulus checks, Mr. Asher, 49, was able to leave a boardinghouse, rent an apartment and take custody of an autistic son, who he feared would go to foster care.

But he said he distrusted “the crooked government” and urged poor people to help themselves. “If you want to change your life, you have to get up and do something — not sit home and get free money,” he said.

Leah Burgess, who also kept her job, drew the opposite lesson from the help she received. A part-time chaplain at a school outside the District of Columbia, Ms. Burgess, 43, is studying for two master’s degrees at Howard University. With three children, she and her husband, who was also a student, received about $18,000 in stimulus checks and expanded food stamps.

The aid helped them eat better and worry less, said Ms. Burgess, who called the support a foundation for a more just society. “If our resources in a pandemic could change millions of people’s lives, then what’s stopping us from continuing to do that?” she said.

The institute projected spending on core programs would more than double, to about $13,900 per family from $5,700 in 2018. The stimulus checks removed more than 12 million people from poverty. Food stamps ended poverty for nearly eight million people and unemployment aid for nearly seven million.

Critics said the aid was poorly devised, noting that many people received more from unemployment benefits than they had earned on the job.

“We spent like we’ve never spent before and we reduced hardship for most people quite dramatically,” said Bruce D. Meyer, an economist at the University of Chicago. “But this came at a very high and unnecessary cost.”

While Democrats and Republicans remain divided over future safety net spending, a bipartisan group of senators agreed Wednesday on about $550 billion in new spending for roads, bridges and physical infrastructure projects, and the Senate advanced the package in an initial vote.

Measuring poverty is contentious, and some conservatives accuse the left of exaggerating the recent poverty reduction to justify more spending. They say the government’s methodology undercounts the benefits people receive and overstates what it takes to meet basic needs. The Urban Institute modified the government’s approach to correct for undercounting, but Ms. Wheaton said methodological issues did not change the conclusion that poverty fell since “we are applying a consistent measure to both years.”

If there are biases in the institute’s methodology, they lean in offsetting directions. Using a 2018 baseline may modestly overstate the recent poverty reduction, since poverty was lower when the virus hit. But the study, which was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, also understated the poverty reduction by omitting several large new programs, including $45 billion in rental aid.

Robert Doar, the president of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, warned that the poverty numbers were being used to attack a successful social compact established a quarter-century ago with the overhaul of the welfare system. Under a new system of time limits and work requirements, payments to poor people without jobs fell, but subsidies for low-wage workers grew. Mr. Doar noted that while liberals warned child poverty would grow, by 2019 it had hit a prepandemic low.

“We required work, we rewarded work, and poverty rates were lower than had ever been,” he said. “The Democrats want to ignore all that and just send everybody a check.”

The evidence of falling poverty in 2021 may seem at odds with reports of increased hunger and other pandemic-era hardships. But the trends can coincide, as Ms. Goodwin’s experience shows. That is because poverty is based on annual income, and help has fluctuated greatly from month to month as a result of policy changes and administrative bottlenecks. Many families have swung between moments of surplus and desperation.

After six years on the job, Ms. Goodwin was shocked to find herself laid off (“that was really a slap in the face”) and distraught when her request for unemployment benefits went unanswered for a month. Fearing she might lose the children to foster care, she drove them 800 miles to Niagara Falls with thoughts of them all jumping in.

“Mentally, I was not in a good place,” Ms. Goodwin said.

A biblical verse on a mural (“Love one another, as I have loved you”) reminded her of how precious their lives together were.

She drove back to Missouri, sought help for depression and joined a support group at a Pentecostal church.

Since then, her jobless benefits swung from a high of $920 a week (much more than she had received on the job) to a low of $320 (much less) as federal policy changed. She lost food stamps for several weeks and fed the children smaller portions. She waited months for stimulus aid after the payment went to a closed bank account.

“It was all very unreliable,” she said.

A low point came last fall, when her jobless benefits bottomed out. The trailer park where she once had worked evicted her.

Ms. Goodwin said she had been looking for work but it was harder than the “Help Wanted” signs would suggest. Fast-food chains say she is overqualified, and the pandemic-era closure of child care centers complicates her logistics. (She previously worked at home.) She started a sideline making church T-shirts and is an apprentice at a nail salon, where she hopes to get hired.

At once a beneficiary and critic of aid, Ms. Goodwin said the safety net, however imperfect, had lived up to its name. “It enabled us to stay out of poverty — that’s absolutely safety,” she said.

Jason DeParle, a reporter in the Washington bureau, has written extensively about poverty, class, and immigration. He is a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the author of “A Good Provider is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century.”