The Timeless Appeal of Tommie Smith, Who Knew a Podium Could Be a Site of Protest

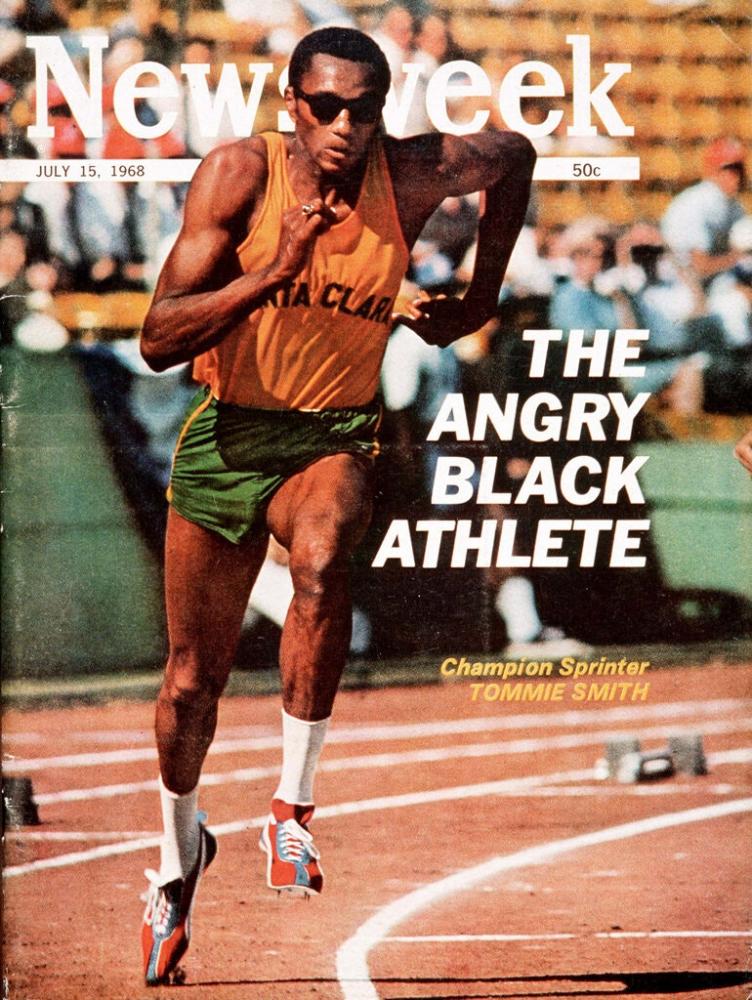

The street vendors along 125th Street in Harlem sell all manner of things: perfume and watches, shea butter and cellphone accessories, paperback books and, of course, T-shirts. One memorable shirt shows three athletes on the medal stand: a white man looking straight ahead and two Black men with heads bowed and arms outstretched, their black-gloved fists raised high in the air. It’s a familiar image, even 53 years after the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, at which the American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos staged one of the most iconic protests of the last century.

On a summer afternoon in 2014, a 70-year-old Smith made his way past the vendors, walking alongside his wife, Delois, and an unlikely second companion, the conceptual artist Glenn Kaino, a fourth-generation Japanese American four years younger than Smith’s eldest son. They were headed to the Studio Museum to see Kaino and Smith’s first collaborative work, “Bridge” (2013), an elevated, undulating pathway forged from gold-painted castings of Smith’s iconic right arm. As they passed the Apollo Theater, Kaino noticed the tees.

“Hey, do you know who’s on this shirt?” he asked an unsuspecting vendor.

“John Smith,” the vendor responded.

“Nope,” Kaino said as the Smiths looked on in amusement. “You know who you have standing before you? You have that man,” he continued, pointing to the slender figure at the center of the T-shirt and then to the older man standing beside him, 6-foot-3 and still physically commanding. “This is Tommie Smith.”

Credit: Kevin D. Liles for The New York Times

It is a measure of the efficacy of Smith and Carlos’s symbolic act that for a time it all but enveloped their individual identities. “When Tommie created the symbol, the value of that moment became abstracted from him as a person,” Kaino explains. “And the appropriation and the use of that symbol from a global sense to represent courage, to represent protest, to represent unity and defiance, all of those things — by the way that symbolic value is created, it necessarily abstracted the symbol from its author.”

What happens when a person becomes a symbol? Smith and Carlos would both see their careers as athletes overshadowed by the moment. The years, decades really, after their defiant act brought struggle and sometimes suffering: hate mail and death threats, broken marriages and psychic pain. Two days after the medal ceremony, longtime Los Angeles Times sports columnist John Hall wrote that “Tommie Smith and John Carlos do a disservice to their race — the human race.” Even many of those that celebrated Smith and Carlos’s act did so under the mistaken belief that they had given the Black Panther salute — something that, for his part, Smith never intended.

What happens when a symbol becomes a person again? The last decade, a time of expanding awareness of racist violence and trauma in the United States, has prompted a dramatic reassessment of Smith. Once pilloried, he’s now lionized. People build statues of him. In 2019, the United States Olympic Committee, the same body that had suspended him from the Olympic team in 1968, inducted him into its Hall of Fame. The Smithsonian collected the clothes he wore on the medal stand: his singlet and his shorts, his track suit and his suede Puma cleats. And, in this new era of protest, a generation of athletes, many of whom claim Smith as a direct inspiration, are channeling the outsized attention that the public directs to sports toward urgent social and political concerns — police brutality, mental health, voting rights and more.

What happens when a person begins forging new symbols, built upon the defining symbol of his youth? The 49-year-old Kaino, with Smith’s active partnership, has produced multiple works of art inspired by the 1968 protest — installations and sculptures, and now an Emmy-nominated documentary, “With Drawn Arms” (2020), which Kaino co-directed with Afshin Shahidi, that charts Smith’s evolution in the public consciousness from pariah to paragon. Kaino understands the art they make together as both a matter of aesthetics and a mechanism for restorative justice. A vivid example of this work is “19.83 (Reflection)” (2013), a full-scale re-creation of the Olympic podium plated in gold; when properly lighted, it casts three ghostly reflections on the wall behind it. “Invisible Man (Salute)” (2018), when approached from behind, appears to be a traditional statue of Smith with raised fist; after walking around it, though, one is confronted by a mirrored front surface, which creates the illusion that the monument has vanished from sight. Both works play with presence and absence, a tribute to how Smith, once banished, defiantly endures.

Kaino admits that he knew Smith “first as a symbol.” After learning in high school about Smith and Carlos’s demonstration, Kaino grasped onto their act as an example of the kind of impact — and the kind of art — he hoped to make. As Kaino’s career flourished, he kept a photograph of the demonstration taped to his iMac. “That symbol, that image works on a number of different levels: emotionally, artistically, politically,” he explains. “And it is my aspiration as an artist to have my work function on a number of different levels, too. So that picture was the high bar — an impossibly high bar.”

Kaino connected with Smith serendipitously after a friend and collaborator working in his studio, Michael Jonte, noticed the image and said, matter-of-factly, “Oh, that’s Coach Smith.” Smith had coached Jonte on the track team at Santa Monica College before moving south, to Stone Mountain, Ga. Soon Jonte and Kaino were on a flight to Atlanta. For Kaino, it was a near-spiritual pilgrimage. He had no specific intention in mind, certainly no vision of what their collaboration and friendship would become. “I never meet someone with the assumption that I deserve their story,” Kaino says. He went, instead, “to try to learn his story; to try to earn his story.”

Smith may not consider himself an artist (“Glenn makes the art,” Smith says, “he has the mind for it.”), but he thinks like one. As a child of nine or 10 years old, working in the California cotton fields with his family, he was drawn to discarded things. “Something laying on the ground or hanging out of a tree,” he says. “I wondered sometimes how a soda pop can got that far out in the boonies. So I’d pick the can up, take it home, and throw it under the house so it had a place to stay.” Through collection, he exercised a curatorial eye and a preservationist instinct. He saw the beauty and the dignity in broken things.

In his years of training his body to achieve world-class speed (at one time, he held 11 world records), Smith exercised his mind as well. In hearing Smith describe his race preparation and execution, Kaino recognized his own artistic praxis. “I’ll make drawings, but I’ll imagine the whole thing and then as we [Kaino and his team] execute them, we’re bringing to life what’s already in our head, that we’ve already imagined,” Kaino says. This exercise of the imagination — whether in athletics or in art — is the foundation of the pair’s shared partnership. “He understands me,” Smith says of Kaino. “I can tell him something and he’ll take it and make it better. It’s a lot of work, but it’s fun work. It’s like training to compete.”

NINETEEN SIXTY-EIGHT was a shattering year in America. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April; Bobby Kennedy, in June. Overseas, 17,000 American soldiers, many of them Black and brown, died in Vietnam; at home, the antiwar movement surged, culminating in violent clashes with law enforcement in Chicago during August’s Democratic convention; the segregationist George Wallace, running as a third-party candidate, was in September polling at 20 percent nationally and would go on to capture five Southern states in the general election; and the summer Olympics in Mexico City, pushed to the fall on account of the heat, was already being called, in the words of a September 30 Sports Illustrated cover story, “The Problem Olympics.”

In Mexico City, the government executed a brutal crackdown on student protesters demonstrating against the corrupt regime of President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. In the United States, Black American athletes threatened a boycott of the games. A group led by the young Black activist and scholar Harry Edwards with the support of key athletes, including Smith, had founded the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) in October 1967. “There are going to be more protests in the future,” Edwards said before the Games. “Black athletes in America have been used as symbols of a nonexistent democracy and brotherhood.” Shortly before his assassination, King lent his support to the movement. As the OPHR’s name suggested, its aim was to fight for human rights on a global scale, from inequality in the United States to apartheid in South Africa and Rhodesia. “A lot of people’s lives were on the line then,” Smith says.

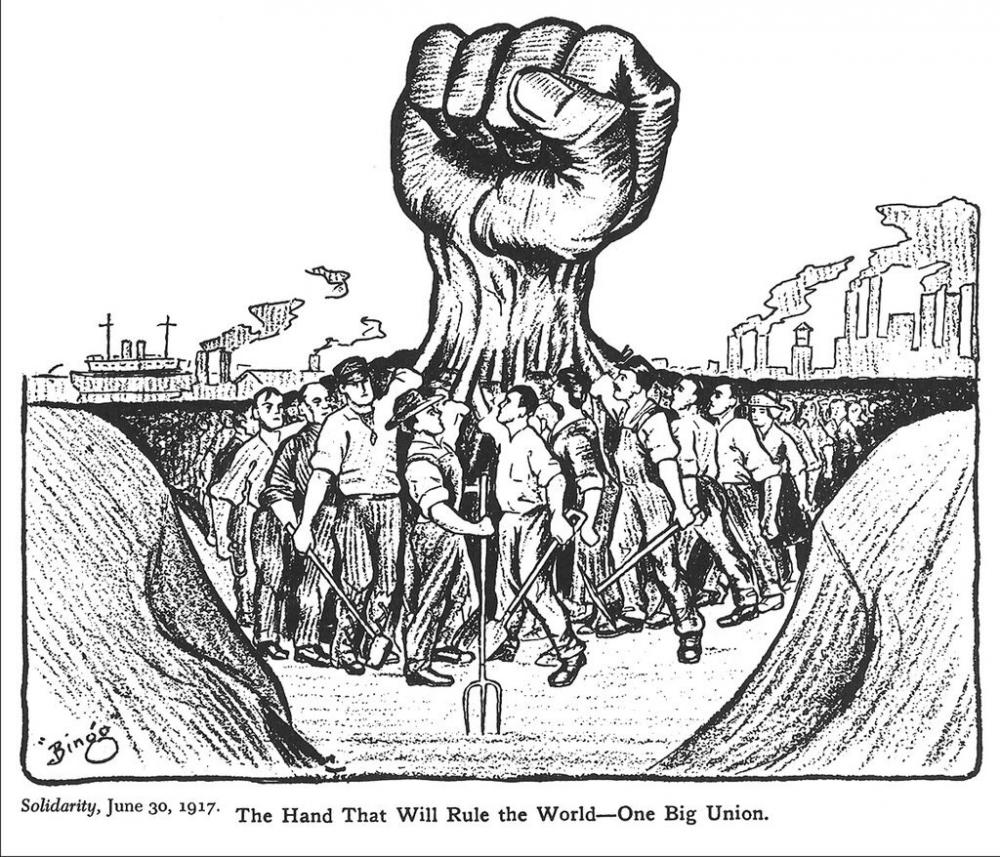

The greatest misinterpretation of Smith and Carlos’s protest was that it was somehow about Black separatism. Instead, Smith insisted, then and now, it was about human rights through the particulars of Black people’s struggle. The Black Panther Party was similarly mis-portrayed as “hating whitey,” even as it was building grass-roots coalitions across racial divides. In forging his antiracism movement, the Rainbow Coalition in Chicago, Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panthers, modulated the Panther slogan “All Power to the People” to be “All Power to All People,” underscoring a common cause. Like the Black Panthers, Smith and Carlos were not ideologically or personally opposed to working with white people; rather, they were against white supremacy, expressed individually or institutionally. That ecumenical spirit was on display on the medal stand with the white Australian silver medalist — Peter Norman — who wore an OPHR button in solidarity with Smith and Carlos and voiced his support to them in words, offering a model of allyship and common cause. Smith knew that the most powerful statement he could create was not in language but in action. “I needed to make a symbol of strength, of power. I needed something to make whole. Not stand up and just do nothing. I needed a movement.” That movement began with a clenched fist.

The history of the clenched fist as an emblem of protest stretches back centuries and across continents. In the visual arts, it is ambiguous in the way that most potent symbols are — it demands context and interpretation. The photographer and curator Francesca Seravalle traces the first work of art to depict a fist clenched in protest to be Honoré Daumier’s “The Uprising” (1848), a painting inspired by the revolution to overthrow Louis-Philippe’s French monarchy. When it comes to work produced in the United States, Seravalle cites a 1917 political cartoon published in the Industrial Workers of the World’s journal, “Solidarity,” which depicts a cluster of factory workers in a ditch with raised fists coming together to form a collective fist rising above the ground.

Smith and Carlos’s protest did not invent the raised fist, but it may well have apotheosized it — distilling it to a forceful and seductive expression of intention. Determining how precisely to project that intention was the product both of planning and improvisation. The scene into which Smith and Carlos entered was festooned with potent symbols: the elevated platforms, the medals, the flags, the anthem, the Olympic rings. Into this crowded symbolic field, Smith and Carlos introduced their own vocabulary of meaning.

Conferring with Carlos in the brief time between the end of the race and the medal ceremony, Smith refined his vision, which had been evolving since the OPHR first proposed a potential boycott of the Games the previous year. In his memoir, Carlos recalls it this way: “Tommie nodded his head with a dead-serious look on his face and then we started talking about the symbols we would use. We had no guide, no blueprint. No one had ever turned the medal stand into a festival of visual symbols to express our feelings.” This was their festival of symbols: Smith and Carlos (as well as Norman) wore pin-back buttons emblazoned with the symbol of the OPHR; they removed their shoes to expose their black socks, a symbol of Black poverty; they donned a pair of black gloves — Smith wearing the right-hand one and Carlos the left — to stand for universal human rights; Smith also wore a black scarf to represent Black pride while Carlos wore a beaded necklace to commemorate Black people killed by lynching. This incomplete list speaks to their clear intentions. But symbols are slippery, subject not simply to interpretation but to manipulation. The agent of them has limited control after introducing them into the world.

One of the distortions that Smith most vehemently rejects is that his actions were somehow un-American. When “The Star-Spangled Banner” began, Smith turned toward the flag, not away from it. “It wasn’t about the flag,” Smith says. “A lot of us Black and brown folks have died fighting for that flag, so I’m proud of that flag, OK? I’m proud of that flag because of what we did to make it our flag.” He bowed his head and closed his eyes not out of disregard for the flag of his nation, but out of reverence, and focused attention on the cause for which he raised his fist, the cause for which he showed his shoeless feet and black socks: that whatever else human rights is, it is also somehow Black.

“I always wanted to do something in my life to make people happily understand,” Smith says. “I called that pose more than once the Cry for Freedom,” he explains, sounding very nearly like a performance artist giving a name to his work.

PERFORMANCE ART, a term that wouldn’t achieve widespread usage until the 1970s, offers a lens through which to view Smith’s actions. Before tens of thousands assembled at Estadio Olímpico Universitario, in front of ABC cameras broadcasting the Olympics live and in color for the first time in history, he and Carlos staged a symbolic intervention. Occupying a public space intended for other purposes; disrupting the orderly exercise of established ritual and convention; recasting and recontextualizing inherited symbols; holding a fixed pose that taxed the body — all of these acts were the result of both political will and aesthetic vision. Performance art is not a medium or a prescribed practice but a mode — art, often spontaneous, unscripted and in the context of community, born in action. What Yoko Ono, one of the early innovators of performance art, once said of her own work applies here as well: “I thought art was a verb rather than a noun.”

Art is bound up with the Olympic Games in more direct, intimate and particular ways than it is with any other sporting event. The father of the modern Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, was an amateur artist himself as well as an art collector. He insisted that the Games include juried competitions in five areas — sculpture, painting, architecture, literature and music — for which artists presented sports-themed works with winners awarded medals as in any other event. (De Coubertin, competing under a pseudonym, took home the gold himself in the inaugural literature competition at the 1912 games.) At their peak, the competitive art events drew over a thousand entrants from across the globe. The last arts competitions were held in London in 1948, after which they were abandoned for not aligning with the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) tightened rules on amateurism.

In spite of this, the connection between art and the Olympics remains, and has been of particular importance to Black Americans, for whom the Games offered one of the first global platforms to display their excellence to the world. Four years after the Mexico City games, at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, the Black American artist Jacob Lawrence was among 29 artists commissioned to design official posters. His contribution depicts five Black relay runners, rendered in Lawrence’s stylized figural flatness and bold colors, their faces contorted by effort and exhaustion as they push toward the finish line. The image pays tribute to the struggles and triumphs of Black athletes throughout the history of the modern Games. More explicit in its critique of the Games, the Black Panther illustrator Emory Douglas’s graphic illustration “The Olympics,” also from 1972, exposes the nightside of Black athletic triumph. In a series of comic-book panels, Douglas illustrates an Afro’ed runner, “USA” emblazoned across his chest, winning a race, mounting the podium with both arms held aloft while waving the flag. In the final, devastating panel, his arms are raised again, this time while he’s held at gunpoint by a white policeman. In the years since, Douglas has illustrated Smith and Carlos’s protest directly, most recently in 2014 with a mural he did with Richard Bell in Brisbane, Australia, titled “We Can Be Heroes.”

Smith and Carlos’s protest lives on in the culture for other artists, too. In addition to Kaino’s longstanding collaborative work with Smith, there’s the Afro-Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth’s 2019 work “DRY CUT (from BLACKS IN THE POOL – Tommie),” a larger-than-life aluminum cutout sculpture of Smith holding his raised-fist pose, which sat outside 30 Rockefeller Plaza in April of that year. And a monumental 23-foot statue by the Portuguese American sculptor and muralist known as Rigo 23 rests on the San José State campus, where both Smith and Carlos once were students.

The most familiar images of the protest, however, are photographs — the best known of which was shot by legendary Life photographer John Dominis. The image captures several things that other images do not. It is the closest; Dominis was only 20 feet away. It is also the most direct, showing the three men’s faces nearly in full. And Dominis framed it to capture the entirety of the symbolic display, down to the stocking feet and up to the brooding night sky.

“I believe when he made that gesture, he was doing it not only for the people but as the people,” says Hank Willis Thomas, another artist who has drawn upon Smith’s protest for inspiration. Willis Thomas’s 2017 sculpture “All Power to All People,” for instance, is a grand tribute to a humble symbol of Black life: the Afro pick, the handle of which is crowned with a clenched black fist. The work pays homage to Smith and Carlos, to the Black Panther Party and to everyday Black folk for whom the comb was both a functional object and an expression of style and pride. “The fist was never meant to belong to anyone,” Willis Thomas says. “The more that it’s used, the longer it lives. And I think that Tommie Smith is immortal because of that gesture.”

Smith achieved many physical feats that October day: winning his preliminary heat despite pulling his groin muscle; competing in the final later that day, injured and without the benefit of having warmed up; winning the 200-meter gold in a world record time of 19.83 seconds, besting his own previous record of 20.00. All of that is remarkable. But how did he remain so resolute on the medal stand for the minute and a half that it took to play “The Star-Spangled Banner”? After propelling his body so swiftly in motion — faster than any man had ever traveled over that distance — he now held it still, though not at rest — his muscles tensed, he maintained his form just as scrupulously as he had during the race. How did he stay so still, willing himself to take the shape of a symbol? “Oh my goodness. No one has ever asked me that before,” he says. Then, he shifts to the third person — and who could blame him, now nearly a lifetime removed from that young man who he once was? “It was a divine motion that took a man and created an image,” he says. “It was no longer Tommie Smith standing; it was the efforts of God that held me.”

IN THE LEAD-UP to this year’s Olympics in Tokyo, the IOC braced for high-profile and potentially widespread political protests — against police brutality and human rights abuses, and in solidarity with marginalized people everywhere. Approaching the Games, the IOC updated its charter three times in 18 months, all in an effort to contain and curtail potential demonstrations by competitors, particularly on the medal stand. Two weeks before the opening ceremony, Smith told the Los Angeles Times that he supported any athlete choosing to protest. “I do think the athletes have a right to say whatever is on their mind, whether it’s agreeable to those who are watching or it’s thought of negatively,” he said. “We are human beings.”

Black women athletes have shaped the story line of these Games, spotlighting issues of intersectionality rather than race matters alone. In the month before the Games, tennis player Naomi Osaka, 23, sparked conversation on mental health when she withdrew from Wimbledon after tournament organizers threatened to expel her if she continued refusing post-match news conferences, which she said triggered social anxiety and depression. The next month, Osaka, whose mother is from Japan and father is from Haiti, lit the Olympic torch at the opening ceremony, thereby carrying that conversation forward. Simone Biles, 24, one of the most celebrated Olympic athletes alive, withdrew during the team all-around on account of mental health concerns that threatened to expose her to physical danger during competition. Though neither athlete raised her fist, their choices of self-preservation as well as their willingness to speak frankly about their well-being stand out as acts of social courage. “You have to be careful about fighting until the end because the end is different for everyone,” Smith said when asked about Biles’s decision to leave the competition. (She would return to capture bronze, her record-tying seventh medal, on the balance beam.)

For all the anticipation about seeing medal-stand protests and symbolic gestures, these Olympics have delivered something quite different: a call for the public to understand athletes not as physical embodiments of national pride but as complex and, at times, conflicted individuals. The closest these Games have given us to a Smith and Carlos moment might have been from Raven Saunders, silver medalist in the shot put, a 25-year-old queer Black woman from Charleston, South Carolina. She kept her arms in front of her during the anthem, but afterward, while photographers took pictures of the athletes on the podium, she raised her arms above her head and crossed them in an X. “It’s the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet,” she later explained.

Perhaps it comes down to this: The symbolic spectacle that Smith and Carlos staged on the medal stand in 1968 can never be reproduced. Its genius and beauty rest in its singularity. Those 90 seconds 53 years ago were a grand display of performance, of art and of performance art. What today’s athletes and artists can — and have — taken from that moment, however, is what Kaino calls the “aesthetic aspects of protest”: the clothing and the emblems, the gestures and the flourishes that draw attention to an imperative need. What remains from Smith and Carlos’s act is irreducible. After 1968, no athletic protest is likely to shock so many for so long. “They’ve kind of retired the singularity of Tommie’s moment,” Kaino says. “It strikes me as the symbol that might always be the most defiant one because they don’t make the context like they used to.” In standing still, Tommie Smith the athlete fell out of time, universal in his particulars. Tommie Smith the man, however, is with us still — called once again to forge symbols of perseverance and hope for a troubled world.

[Adam Bradley is a scholar of African American literature and a writer on black popular culture. His commentary has appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post as well as on PBS, NPR, and C-SPAN. He is the author or editor of several books, including Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop and The Anthology of Rap. Most recently, he collaborated with the rapper and actor Common on Common's memoir, One Day It'll All Make Sense.]