Healthy Group Accountability: Learning How to Learn

Earlier this year, Organizing Upgrade ran a set of articles exploring leadership and accountability. Cathy Dang-Santa Anna kicked off with lessons from building peer accountability in a community organization, Kathleen Mulligan brought the experience of an innovative leadership development project in the labor movement, and Lauren Jacobs reflected on the processes and perspectives needed to develop new generations of leaders. Now Michael Strom and Joshua Kahn Russell pick up the thread, offering frameworks that can help us do the continual learning and summation that are so essential to building strategy.

A team of facilitators from our organization, The Wildfire Project, was invited to support a base-building group whose staff was absolutely burnt out. Our first workshop brought their staff together with a volunteer leadership team (from their base) who, until then, had been minimally engaged. Staff shared their overwhelm and laid out their workload. It was clear that unless the whole group took collective ownership and responsibility for the direction of the organization, it would collapse.

We ended that first session together on the other side of that breakthrough: feeling grateful, connected, and on-purpose. But the more difficult work began when we came back together to make that vision of shared leadership real. We dug into a process of reimagining the structure, roles, and expectations for a more active volunteer leadership team. That discussion ran aground on fears about the accountability such a new structure would require.

Like most of us, they had many negative experiences of “accountability.” They worried that holding each other accountable might break their relationships, undermine their care for each other, and replicate the worst dynamics of other groups they’d been part of. They worried that if they held each other to high expectations, some people would not meet them and would have to leave.

The group had a choice to make. Their old way of being was clearly not working. They’d been stuck setting lowest common denominator expectations, where the people with the least capacity (or most objections) determined what was expected of everyone. The bulk of the work fell to a handful of people who’d become burnt out and resentful. It was hard to get everyone together in a room for long enough to actually build alignment or make key decisions. They had stopped growing.

Yes, if they raised their expectations of each other, some people might have to leave. But if they didn’t change anything, they risked the organization falling apart.

The breakthrough came when they looked to their base.

They ultimately decided that achieving the group’s purpose (meeting the needs of their base), required them to hold each other with both compassion and rigor. Accountability was actually a requirement on the path to power and transformation.

Two years later, the staff and leadership are thriving. Everyone is clear on what’s expected of them, and regular, compassionate feedback is a core part of their organizational culture. The staff and leadership team recently completed an eight-month strategy process that included study, debate, and making some hard decisions about their work. None of this would have been possible if they weren’t able to hold each other accountable in healthy ways and rise to the standards their work deserves.

PATTERNS SEEN IN PRAXIS

In order to build effective strategies, we need to be able to assess our conditions, evaluate our actions, and integrate new information. In other words, we need to be able to learn effectively. The direct education approach cultivated by Training for Change argues that to truly learn effectively, we have to be able to show up authentically, build enough trust to take risks and make mistakes, and meaningfully face tension and difference.

At The Wildfire Project, our work supports movement groups to build organizational cultures that do just that. We envision a Left made up of groups that have the skills to hold each other through the vulnerable and crucial work of imagining, debating, taking risks, and even failing and trying again.

Interpersonal accountability is a key component of healthy organizational culture – one that emerges as a site of growth and tension again and again in our workshops. There are currently a number of conversations in movement circles using the term “accountability” in the context of repairing harm that someone has caused. That’s not what we’re referring to here – we’re talking about accountability in terms of interpersonal follow-through on group expectations, responsibilities, and commitments. What happens when someone doesn’t complete a task they agreed to? How does the group respond?

We know that follow-through is critical if we want to implement any of our plans. And yet many of our organizations struggle when they need to respond to a plan breaking down or to someone breaking their word, often either leaning into impersonal and punitive disciplinary procedures or getting caught in reluctant avoidance (and sometimes an ambivalent combination of the two).

Past unhealthy or exploitative experiences with accountability are often a driving factor in this difficulty. Many of us come to the work having been “held accountable” in families, workplaces, or broader communities in punitive, shaming ways that we never agreed to. In response, we might resist being held accountable in our organizations or fear that we’re reenacting harmful patterns when we hold others accountable. It might feel like holding someone accountable risks breaking relationship and pushing them away. Or it can feel like we can’t tolerate the possibility that some people will be “in” and others “out” if we hold everyone accountable to expectations.

HEALTHY VS. UNHEALTHY ACCOUNTABILITY

We need ways to explore our experiences of holding – and being held – accountable. Then we can distinguish between what supported our growth and power and what made us feel shamed, controlled, or isolated. From there, we can begin to build a vision of accountability that aligns with our values and supports us to achieve our purpose. Wildfire has supported groups to do this kind of reflection and align on qualities of healthy accountability rather than qualities of unhealthy accountability. These often share some key themes:

Qualities of Unhealthy Accountability:

– Punitive; Driven by an explicit or implicit motivation to make someone hurt or “pay for what they’ve done.”

– Transactional; focused solely on product/outcome in a way that ignores circumstances that caused the breakdown and the work of maintaining relationships.

– Reactive; accountability only comes into play after someone has broken their word/acted out of integrity, with no support systems beforehand.

– Over-accountable (a term from generative somatics); sacrificing personal boundaries or looking to hide through appeasing.

– Under-accountable (also a term from generative somatics); avoiding, disappearing, becoming non-responsive, or shrinking away from accountability.

Qualities of Healthy Accountability:

– Puts consequences and impact over punishment: The goal is not to make someone hurt because they messed up, but to face the natural consequences required to repair impacts on the work and each other.

– Says “you did something bad,” not “you are bad”: Faces the impact of someone’s behavior without making them fundamentally wrong.

– Focuses on deepening relationships and growing in community, not just producing outcomes.

– Stays grounded in the wholeness, complexity, and context of each person’s life.

– Roots itself in shared purpose and values, not random, arbitrary, or bureaucratic rules or whims.

– Is driven by curiosity over judgement.

– Cultivates and assumes good intentions.

– Operates consistently over time, not just after a breakdown, includes clear process and expectations and ongoing follow up/follow through.

– Relies on collective responsibility. Every member of a group has a role in maintaining an accountable culture.

This alignment on the values that drive a group’s vision of accountability (particularly when rooted in reflection on group members’ own successes and struggles with accountability) often enables the group to release fear and resistance that have been blocking them from building an accountable culture.

PATH TO TRANSFORMATION

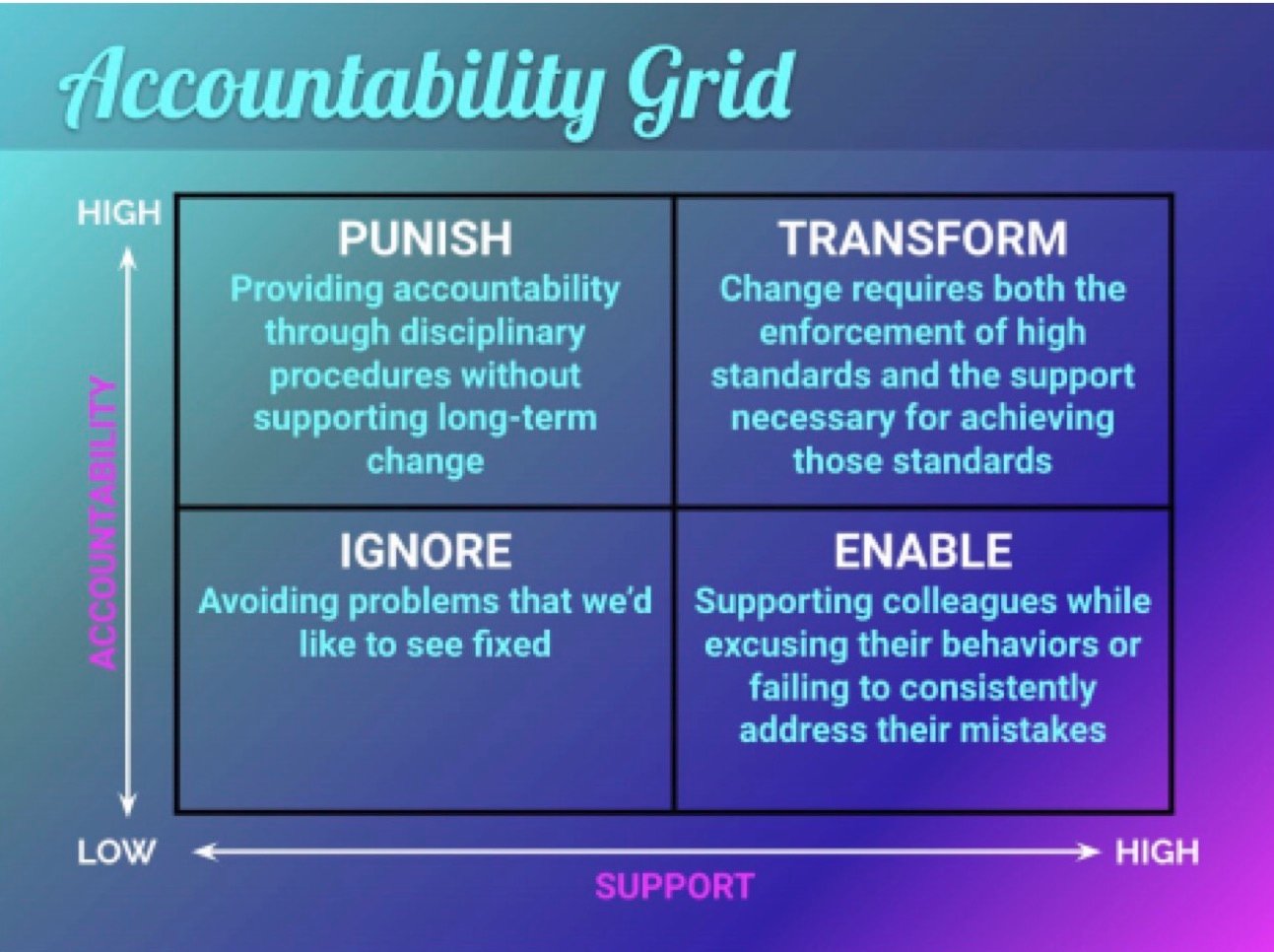

Here is an example of a framework we have adapted from Just Practice and Wildfire facilitator BJ Star developed for use in our slides during online facilitation. It shows a spectrum of how attempts to create accountability play out in contexts of high and low support, and the conditions for transformation to occur:

ACCOUNTABILITY FOR GROWTH, HEALING AND PURPOSE

The above framing of healthy accountability allows us to enter into accountability in service of transforming our world and ourselves. Our thinking on accountability has been shaped by Transformative Justice movements led by women and trans people of color, Marxist practices of criticism/self-criticism/summation, and the organization generative somatics.

We know that, when it’s done right, accountability offers individuals opportunities to let ourselves be seen and related to authentically, even and especially when we’ve made mistakes. It can build our capacity to trust ourselves and our relationships, and hold us to our purpose, values, and growing into who we long to become.

Similarly, healthy accountability offers groups opportunities to transform.

Every time a group breaks its word and doesn’t address it, the group loses trust in itself. This is common in the Left: groups set vague intentions that they rarely actualize instead of material goals that they can measure, or create unrealistic work plans that they don’t deliver on. It is important to emphasize that this behavior is often independent of individuals breaking their word, but is part of the group organism. It is not the lack of follow-through that breaks a group’s faith in itself, it is the failure to acknowledge it and make changes.

Even something as simple as breaking an agreement to end meetings on time can undermine a group. People might feel that their time is not being respected and start arriving late, leaving early, or checking out. Important items might get dropped from agendas in the time crunch. Those able to stay late might start to feel resentful of those who don’t attend full meetings. Behind each of these dilemmas is the feeling “This group doesn’t do what it says it will do, so I have to act accordingly.”

Practicing collective, healthy accountability can help a group move from doubt, shame, and avoidance to believing in itself. Sometimes we imagine that believing in the group is what drives action, that if the mission and vision are compelling enough, people will reliably participate. But it can actually work the other way around: when a group does what it says it will do, members often come to believe its vision and mission are possible and worthwhile.

Though many of us fear that holding each other accountable will break our relationships or make people leave, healthy accountability actually does the opposite. It brings groups into deeper, more trusting and reliable relationship. In fact, healthy accountability is vital to authentic relationship. Part of holding each other is holding each other accountable.

Healthy accountability helps a group become a place where its members can let themselves be seen, whole and complex. In the work of showing up accountably, we have to learn to really listen to ourselves, feel our boundaries, and communicate our needs. These are all things trauma and oppression work to take away from us. Accountability becomes a fundamental component of healing these wounds. It’s an essential part of building groups where we transform ourselves as we work to transform the world.

The Wildfire Project seeks to normalize the group behaviors and practices required to genuinely learn from our mistakes. Healthy accountability doesn’t just help groups get things done, it helps them grow and become the most powerful versions of themselves. Conversely, groups are less resilient to shifting politically when they don’t build the “muscle memory” of regular default accountability practices that work for their own internal culture. When we understand accountability in this way, it is clear how crucial it is to becoming students of our own context. Accountability is a dialectical approach to growth. It’s a generative set of tools to make our groups healthy, which they need to be if we’re going to weather the changing terrain ahead to win a governing coalition in this country.