‘It didn’t adhere to any of the rules’: the fascinating history of free jazz

When Miles Davis first heard the music of Eric Dolphy, a key figure in the free jazz movement, he described it as “ridiculous”, “sad” and just plain “bad”. Upon encountering the early sounds of free jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman, Thelonius Monk said “there’s nothing beautiful in what he’s playing. He’s just playing loud and slurring the notes. Anybody can do that.” The editors at the jazz world’s bible, Downbeat Magazine, went further, initially criticising the entire genre as a force that’s “poisoning the minds of young players”, jazz critic Gary Giddens recalled.

Given the revolutionary nature of the music, it’s no surprise that many in the field greeted it with such disdain. “Free jazz didn’t adhere to any of the rules of what was considered music at the time,” said Tom Surgal, director of the new documentary Fire Music, which covers the history and breadth of the movement. “There wasn’t a single musical tenant this music did not defy.”

That included everything from its approach to chords to the placement of the beat to the role of the solos to the basic notions of melody and harmony. Atonality and abrasion were embraced, polyrhythmic and polytonal modes were amplified and risk idealized, paving the way for some of the most extreme and, to some ears, difficult, music ever made. As even Surgal admits, “this is not easily digestible music”.

A foundational figure in the genre, Cecil Taylor, had a word of advice about that. “The same way that musicians have to prepare, listeners have to prepare,” he said in a vintage interview used in the film. But when the movement started in the late ‘50s and early 60s, few were in any way prepared. Bebop ruled jazz at the time, exemplified by well-established stars like Max Roach, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, each of whom presented then codified approaches to solos, rhythms and melody. As exciting, erudite and skilled as their work may have been, their approach had become familiar enough to spur artists like pianist Taylor and saxophonist Coleman to seek something new.

Taylor began to capture that on record with his 1956 debut, Jazz Advance, in which he displayed a highly percussive approach to his instrument, performing with equal degrees of energy and technique. The music created by his quartet expanded the use of improvisation, bringing a wildness to original pieces, as well as standards like Cole Porter’s You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To. On Taylor’s two albums released in 1960, Air and The World of Cecil Taylor, he pushed further, leaving more traces of bebop behind to play in a world of his own making.

Coleman followed a similar trajectory. His first album, Something Else!!!, issued in 1958, had a daring that would grow exponentially. The title track of his 1960 album, Change of the Century, could be taken literally as it heralded fresh ways to balance dissonance, cacophony and virtuosity. But the real line-in-the-sand moment didn’t arrive until the next year, with the release of an album that gave this emerging style both its name and its mission: Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. Credited to the Ornette Coleman Double Quartet, the set featured two self-contained groups of players performing at once. Each quartet featured a bass and drum player as well as two wind instruments. On the left channel listeners could hear Coleman on sax and Don Cherry on trumpet; on the right Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet. The near 40 minutes of music they spun represented an almost unbroken improvisation, anchored by a few set sections that, ironically, tended to be the most disruptive. Still, the result had its own sense of order and logic, not to mention a surprising beauty, once you adjust to it. “This wasn’t a musical circle jerk,” said Surgal. “It was a symbiosis. There’s a lot of interplay and empathy at work. It’s very much about musicians listening to each other.”

It’s also about their balance of freedom and discipline. “Improvisation is informed by passion and conditioned by knowledge,” Taylor said in a vintage interview used in the film.

As controversial as this work may have been at the time, Surgal said its creators didn’t feel they were in any way refuting their predecessors. “The free jazz musicians weren’t casting aspersions on what came before,” he said. “In their minds, they were simply creating the next step.”

More, even the wildest of them had firm roots in established genres, informed by music from the places in which they grew up. In the music of the Fort Worth-born Coleman, for instance, Surgal believes “you can hear the rough-hewn Texan sound of Arnette Cobb or Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis. To me, Ornette was always playing the blues. He just had a unique interpretation of it.”

The freshness of such interpretations mirrored parallel mid-century movements in the worlds of art and literature. Its accent on improvisation and internalization echoed both the Beat authors’ love of spontaneous writing and the attitudes and techniques of the abstract artists of the era. (The cover of the Free Jazz album featured a reproduction of Jackson Pollock’s 1954 painting The White Light). Likewise, the music’s anger and edge reflected the politics of the day. “This music was coming out of the civil rights movement which metamorphosed into the Black militant movement,” said the director. “It also reflected the anti-war movement. The cry of wailing saxophones and the beating of drums was the perfect compliment to the radicalism in the air at the time.”

At the same time, the exploratory quality of the music reflected the musician’s experimentation with their own psyches. “A lot of the free jazz musicians, especially the ones in New York, were experimenting with hallucinogens and that experience was informing the music,” Surgal said. “In many ways, this is the undocumented psychedelia.”

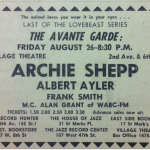

Small wonder, the rock musicians of the day took note. The expansive and noisy solos of late 60s psychedelic rock used some of the principals of free jazz to blow out the bounds of the blues that first inspired them. The fractured guitars in songs like The Byrds’ Eight Miles High borrowed from the angularity and skittishness of free jazz. Leader Roger McGuinn has often spoken of the cues he took from John Coltrane, who himself moved from bebop to the world of free jazz with his classic, 1966 album Ascension. Paul McCartney listened to the music of free jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler while writing songs for the Revolver album and various Beatles attended shows by the London-based free improv band AMM. You can hear the clear influence of this music on British art-jazz bands like Soft Machine as well as on the avant-garde UK.keyboardist Keith Tippet, who channeled the very soul of Cecil Taylor with his unhinged piano work in pieces like King Crimson’s 1970 single Cat Food.

Coleman’s frenetic style didn’t only influence the sounds of musicians but, in one prominent case, the movements. After a young Iggy Pop heard Coleman for the first time, he had a revelation: “I can do that,” he told a reporter, “with my body.”

By the mid-70s, a second wave of New York avant-garde players created a scene of their own. Due to their difficulty in getting gigs, they began hosting shows in their own living spaces, spawning the loft jazz movement. Their efforts just preceded, and sometimes mingled, with the city’s no wave “punk jazz” movement, led by acts like The Contortions, Mars and DNA.

Not only did the New York-bred free jazz movement impact artists beyond the genre, it also seeded scenes across the US, in places like Chicago and St Louis, as well ones in Europe and the UK. In one case, it may even have had a connection to outer space: Free jazz artist Sun Ra claimed that he and his music came straight from Saturn. Importantly, each of these artists and scenes had their own take on the music. “Free jazz is not one thing,” said Surgal. “This music is nothing if not varied.”

At the same time, the artists found unity in their uncompromising nature. Unfortunately, that often made it difficult for them to make a living. Club owners were resistant to it, so gigs were hard to come by, at least in the US. The film chronicles several attempts by the musicians to organize themselves to gain decent pay, but their independent natures made coordinated efforts a challenge. More, the movement was marred by the young deaths of some of its central players during its prime era. In 1964, Eric Dolphy died at the age of 36 from issues related to his undiagnosed diabetes. Three years later, Coltrane succumbed to liver cancer at 40, and Ayler died in a presumed suicide in 1970 at 34.

By the 1980s, key parts of jazz began to take a more conservative turn. A new movement, dubbed rebop, aimed to return the genre to pre-free jazz values. Surgal blames the subsequent refutation of the avant-garde on “a conspiracy of revisionists”. He fingers, in particular, “Wynton Marsalis and his brother Branford who have done everything they could to minimize the exposure of this music and to denigrate its contributions. The critic Stanley Crouch led the assault.”

Meanwhile, in the world of alt-rock, devotees abound, from Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and Nels Cline of Wilco (who each serve as Executive Producers of Fire Music), to members of Superchunk. Today, some young, math-rock groups, like Black Midi and Squid, have applied free jazz’s dissonance and mania to guitar-oriented sounds. However well-regarded many of these musicians may be in certain circles, however, Surgal sees them as outsiders and so, by necessity, exemplars of the DIY tradition. “DIY is normally used in relation to punk or hardcore but these guys were the OGs of that,” he said. “They had to self-release records and find alternative places to play when they were turned away by the clubs. Their story is a great example of self-determined people who believed in a sound they knew deserved to be heard.”

-

Fire Music is out in New York on 10 September and LA on 17 September with a UK date to be announced