Ahmaud Arbery: Trial of Accused Murderers is Test for Racial Justice ‘in the Heart of White Supremacy’

Beneath the Spanish moss that swayed from an oak tree, Diane Arbery Jackson took a seat in the morning shade as the three white men accused of murdering her nephew sat in the courtroom a few feet away.

For the past two weeks, Arbery has attended the jury selection process at the Glynn county courthouse every day. And every day, bar one, she has elected to stay outside on the grassy courtroom grounds.

“It hurts to be in the same room as them,” she said. “It’s hard when you look at them, you think: ‘How could they do a child like that?’ Ahmaud was a good kid. All you had to do was stop and talk to him. You didn’t have to go out to him with no guns.“But I know God is going to deal with them.

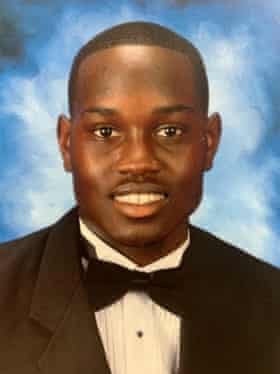

”Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed in Brunswick, Georgia, on 23 February 2020. Photograph: Reuters

It was February last year when Ahmaud Arbery, a Black 25-year-old, was jogging in the small coastal town of Satilla Shores. The three men accused of murder, Gregory McMichael, 67, his 35-year-old son Travis McMichael and their neighbor William “Roddie” Bryan, 52, all pursued Arbery claiming they suspected him of involvement in a series of burglaries in the neighborhood. Arbery had been recorded on surveillance footage entering and leaving a semi-constructed house in the area, but no evidence has linked him to any offense.

A scuffle occurred as the McMichaels, both carrying firearms, attempted to corner Arbery, who was unarmed, with their pickup truck. Travis McMichael then opened fire three times with a shotgun.

On Tuesday, after 11 days of jury selection, a panel of 65 jurors was finally selected from a pool of hundreds. Barring any unforeseen delays, including last-minute motions defense attorneys have suggested they will file, a final jury of 12 and four alternates will be seated this week, with opening arguments to follow, probably on Thursday.

The trial of the three men, who have pleaded not guilty, occurs six months after the conviction of Derek Chauvin, the white former police officer who murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis after pinning his neck to the ground for nine minutes and 29 seconds. That trial was undoubtedly a landmark moment for police reform advocates around the country, but, say many observers, the case of Ahmaud Arbery is a sterner litmus test for the state of racial justice in the US.

Lee Merritt, a lawyer representing the family of Ahmaud Arbery, stands by a mural in the likeness of Arbery painted by artist Theo Ponchaveli in Dallas, Texas. Photograph: Tony Gutierrez/AP

“This case is almost a straight line from Emmett Till,” said the civil rights attorney Lee Merritt, who represents the Arbery family. “Our legal system is statistically and continuously biased but it’s more of a test than Minneapolis and George Floyd because we are in the heart of white supremacy here in south Georgia.”

Merritt’s point was illustrated by the immediate surroundings. He spoke to the Guardian on the steps of the courthouse – less than a mile away a monument to the Confederacy, wrapped in protective plastic since the start of the trial, still stands in a local park. City officials have said it will eventually be removed.

But the legal particulars of this murder trial also point to history as well. The McMichaels’ defense is expected to hinge on a now defunct Georgia law that traces its roots to the state’s era of slavery and essentially allowed private citizens the power to arrest people if they had “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” of a felony being committed.

In the wake of mass protest following Arbery’s death, Georgia’s Republican governor repealed the law, but attorneys for all three defendants are expected to utilize it throughout the trial.

“They changed the law, but changing the law doesn’t affect us. It doesn’t change what was the law of the land at the time,” said Bryan’s defence attorney, Kevin Gough, last month.

A rally to protest against the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery, in Brunswick, Georgia, in May 2020. Photograph: Stephen B Morton/AP

The backstory to the prosecution, too, points to evidence of insider politics and institutional racism in the local criminal justice world here.

One of the first prosecutors assigned to the case, George Barnhill, initially recommended not charging any of those involved, claiming the pursuit was “perfectly legal” due to citizen’s arrest statutes. Barnhill, who had a chequered history of aggressively prosecuting Black residents in his jurisdiction, eventually recused himself from the case. Another former prosecutor initially assigned the case, Jackie Johnson, has been criminally charged for alleged misconduct in the process as Gregory McMichael had worked as an investigator in her office.

The past two weeks have also highlighted the difficulties in impaneling a jury in this small rural county, composed of 69% white residents and 26% Black residents, and which voted 61% for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. Defense lawyers have argued many potential jurors have not shown up for jury duty as the court whittled the final number down to 65 people. Prospective jurors were questioned about their prior knowledge of the case, whether they had expressed support for the Black Lives Matter movement, and if they knew any of those involved.

In a striking remark on Friday last week defense attorney Gough complained to the judge: “It would appear that white males born in the south over 40 years old without a college degree … which he might also be known as Bubba or Joe Sixpack … seem to be significantly underrepresented.”

Still, despite these hurdles, Merritt was explicit about his expectations for accountability in the case: “We expect convictions on all charges. These men should be in prison for the rest of their lives. That will get us on the road to justice.”

Among the small group of activists seated on the grass outside the courthouse was 68-year-old Patricia Fields, from the nearby town of Waycross. Like Diane Arbery Jackson she too has come to the courthouse every day and, in a recent week, went to visit Satilla Shores, the small neighborhood where Arbery was killed.

“It’s eerie there,” she said. “It feels like there’s a shadow over it. That something is just not right.

”People participate in a protest outside the Glynn county courthouse in Brunswick, Georgia, on 8 May 2020. Photograph: Erik S Lesser/EPA

On a trip earlier this week few residents of Satilla Shores wanted to speak about the Arbery murder case. Along neatly kept lawns, a number of houses still display Trump 2020 presidential campaign placards and a golf cart was daubed in a sign that read: “Impeach Biden”. There is no memorial or marker at the site where Arbery was gunned down.

For a case that is tied so deeply to atrocities of the past, the murder of Ahmaud Arbery is also closely linked to prosecutions from recent memory.

The presence of eyewitness video, filmed by Bryan as he took part in the pursuit from behind, is set to play a pivotal role in the case. It took months for the footage to emerge, as the case sat in relative obscurity away from the gaze of most national media. The absence of publicly available footage undoubtedly contributed to the initial decision not to indict the three men now standing trial. It was not until the video was made public that the case was handed to Georgia state investigators who promptly recommended charges against the accused.

In the same way that Darnella Frazier’s eyewitness video of the murder of George Floyd thrust the incident into global consciousness and played a pivotal role at the trial of Derek Chauvin, so too does this footage hold the key to the case.

The trial also bears striking similarities to the prosecution of George Zimmerman, charged with the murder of the unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin in the neighboring state of Florida in 2012. Zimmerman, a volunteer neighborhood watchman who shot and killed Martin after chasing him down for “suspicious” activity, was acquitted at trial claiming self-defense under stand your ground statutes – a similar line of argument tied to self-defense that the McMichaels are likely to make at trial.

Crucially, however, there was no witness video in the Zimmerman trial.

Diane Arbery Jackson ate lunch on the lawn; shrimp, corn and grilled potatoes, donated to the small group of activists by a local racial justice coalition. She told the Guardian of her fondest memories of her nephew, whose death prompted the state of Georgia to ratify its first hate crime statute in June last year.

“He always showed love to everybody,” she said. “Every time he sees you, he always gives you a kiss. ‘I love you,’ he always said. ‘I’m good.’”

She described her family’s history in Brunswick, which dated back to beyond the civil rights era. Her father and grandmother had marched in the 1960s, she said and were beaten by white residents.

“And that’s why we’ve got to keep doing this, so we can keep going where they left off at. We have to come together as a community and continue the fight.”

Oliver Laughland is the Guardian's US southern bureau chief, based in New Orleans