Nagasaki: The Last Bomb

At 3:47 a.m. on August 9, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress took off from the American airbase on the island of Tinian, in the North Pacific Ocean. Operation Centerboard II, the mission to drop the second atomic bomb on a Japanese city, had begun. Already things were not going as smoothly as they had three days earlier, in the run over Hiroshima. That attack had been textbook—“operationally routine,” as a classified Army history later put it. The Enola Gay had reached its target and returned home without complication; an announcement sent out under President Harry Truman’s name had trumpeted its success. But Bockscar, the strike plane chosen for Centerboard II, had been delayed on the tarmac because of fuel-pump problems. Only the day before, four B-29s in succession had crashed on takeoff, causing extensive fuel fires. As one of the scientists on Tinian wrote, “We all aged ten years until the plane cleared the island.” But clear the island it did.

Bockscar had been stripped of most of its armor and weaponry to accommodate its five-ton atomic payload, known as the Fat Man. Thirteen minutes after takeoff, at 4 a.m. Tinian time, the weaponeer made his way aft and removed two green safing plugs from the bomb, replacing them with red arming plugs: it was now live. Whereas the weapon dropped over Hiroshima had been a relatively squat cylinder, this one was shaped like a giant egg. It was five feet around and eleven feet long and painted mustard yellow. At one end was a rigid, boxy tail fin known as a California parachute, designed to help keep it from spinning wildly once it was released. The pit crew who assembled it had signed their names on the casing, and some also wrote messages to the Japanese—“Here’s to you!” and “A second kiss for Hirohito.” On its nose, the bomb bore a stenciled acronym, jancfu, which stood for Joint Army-Navy-Civilian Fuckup.

The plane beat its way through dark and stormy skies for six hours before it arrived over the small island of Yakushima, where it was to wait for two accompanying B-29s, the Great Artiste, which was outfitted with instruments to help assess the power of the bomb, and Big Stink, a camera plane. Big Stink never showed. After fifty minutes, Bockscar and the Great Artiste proceeded to their primary target, the city of Kokura. It had a population of a hundred and seventy-eight thousand, about half that of Hiroshima, and was home to what U.S. military planners called “one of the largest arsenals in Japan.” The Enola Gay, now serving as a weather plane, had radioed that conditions were good.

The crew had been expressly ordered to pick out their target visually, rather than by radar, since the explosive reach of the bomb, although astonishing, was still limited enough that to be off by a mile or two might result in the majority of its power being wasted. (Radar bombing was particularly susceptible to this sort of error.) When Bockscar arrived over Kokura, at 10:45 a.m., the crew found that the arsenal was “obscured by heavy ground haze and smoke,” according to the weaponeer’s flight log. Over the years, three explanations for this change of fortune have been offered. One is that the weather turned. Another is that the smoke came from the American firebombing, the day before, of the adjacent city of Yawata (a nice bit of irony, if true). The third possibility, as has been claimed in recent years by several former technicians at a major electrical power station in Kokura, is that the haze was an intentional release of steam, created as a matter of routine when the first B-29, the Enola Gay, was spotted. For whichever reason, if not all three simultaneously, the visual bombing of Kokura couldn’t be managed. After forty-five minutes, and with anti-aircraft fire headed their way, the crew decided to try for the secondary target: Nagasaki.

When we remember the destructive birth of the nuclear age, we tend to focus on Hiroshima. It was first, and firsts get precedence in memory. It was also more devastating an attack than Nagasaki, with nearly twice as many dead and injured and three times as much land area destroyed. (This was in spite of the fact that the Little Boy, the bomb dropped by the Enola Gay, was only three-quarters as explosive as the Fat Man.) But if Hiroshima was, from a military perspective, relatively well considered, well planned, and well executed, Nagasaki was almost the opposite. From the very beginning, it was a jancfu—a sign that this new era was as likely to be a comedy of errors and near-misses as the product of reason and strategy.

Years after the bombing, General Leslie Groves, the micromanaging head of the Manhattan Project, admitted that he had never been able to figure out exactly when or why Nagasaki “was brought into the picture.” It was included on an initial list of seventeen potential targets, in late April of 1945, but by early May it had been weeded out. Although the city manufactured engines and torpedoes and was an important port, it was also home to an Allied prisoner-of-war camp, which made it less attractive. And, from a targeting perspective, it had difficult topography. Hiroshima and Kokura had their industrial and urban areas concentrated on relatively flat ground—ideal for the intense blast pressures produced by an atomic bomb. Nagasaki, however, was a city within valleys, divided in two by mountains, without a large, coherent center.

Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura were the first four targets chosen, with Niigata as a runner-up. Soon thereafter, following a round of firebombing, Yokohama was removed from the list; the U.S. military preferred targets that had not already been damaged by conventional munitions, which would make it hard to see the effects of the new weapon amid the old rubble. Kyoto was later excluded, too, because of its cultural importance. This left Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. Along with Kyoto, these three cities were added to a list of “reserved areas.” They would be spared other attacks and saved for the bomb.

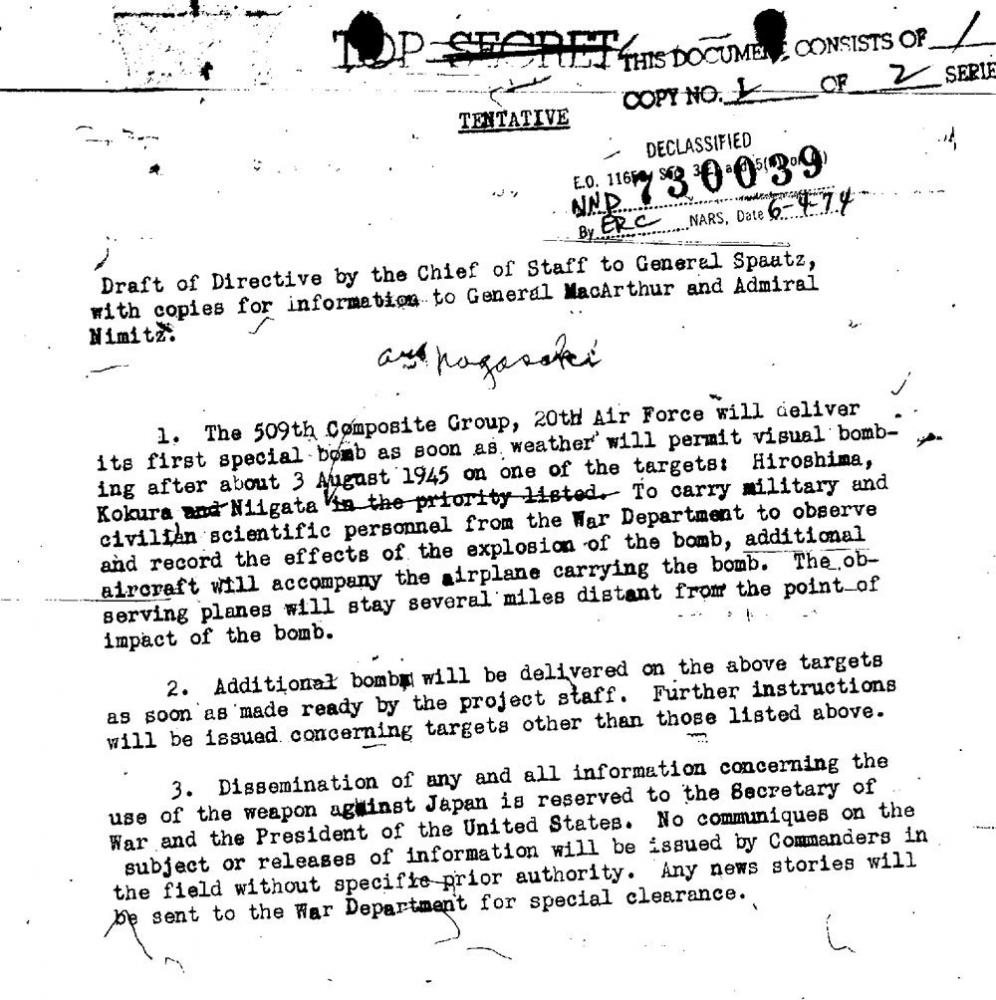

Nagasaki was never reserved. In fact, it was bombed conventionally no fewer than four times before the Fat Man was dropped, including a little more than a week before Operation Centerboard II began. The city was not added to the list until the day before it was finalized. The draft version of the strike order, written on July 24, 1945, gave the targets as “Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata in the priority listed.” On the version in Groves’s papers, in the National Archives, someone has crossed out “in the priority listed” and scrawled in “and Nagasaki.”

Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Bockscar arrived at Nagasaki at 11:50 a.m. Tinian time, by which point it had been in the air for nearly eight hours. Given the plane’s mechanical problems, the crew were close to the point at which they would have to turn back or risk ditching. To have any hope of making it to a friendly airbase they would likely have had to drop the Fat Man into the ocean. “Less than two hours of fuel left,” one of the pilots wrote in his mission diary. “Wonder if the Pacific will be cold?”

Nagasaki had clouds, too. It was the bombardier’s twenty-seventh birthday, and as Bockscar made its way over the city he searched for an opening. The prescribed aiming point was the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, which covered an area about half a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide at the mouth of a valley, along an inlet from the ocean. “I got it! I got it!” he suddenly shouted. Control of the aircraft, and of the ability to drop the bomb, was turned over to him. Forty-five seconds later, the Fat Man was released. Bockscar banked, to put distance between it and the imminent inferno.

The Fat Man detonated at two minutes after noon, sixteen hundred and forty feet above the ground. According to the readings that had been collected at the Trinity test, three weeks earlier, in New Mexico, this altitude would maximize the destruction done to light wooden buildings (the sort that civilians lived in). Color footage of the explosion was filmed from the Great Artiste. It shows the nearby clouds moving out, propelled by the shockwave, and the remains of the nuclear fireball, pink and orange, rising, turning in on itself, becoming white. The cameraman pans up and down, taking in its full height. There was death and chaos on the ground, but from the air there was just the mushroom cloud.

Did the bombardier actually see his target? Postwar recollections are uncertain. The physicist and future Nobel Prize laureate Luis Alvarez, who was an observer on the Hiroshima mission, later wrote that he always took the story about the last-minute hole in the clouds “with a grain of salt,” noting that the errors in placing the bomb were similar to those that occurred with radar bombing. Ground zero ended up being some three-quarters of a mile off target, close enough to the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works to destroy it and far enough north to take out a torpedo factory in a different part of the city.

But the bomb only achieved this unexpected double success because it went off over a mostly civilian district. The U.S. military’s official damage map, produced in 1946, labels the structures within three thousand feet of the detonation point: Nagasaki Prison, Mitsubishi Hospital, Nagasaki Medical College, Chinzei High School, Shiroyama School, Urakami Cathedral, Blind and Dumb School, Yamazato School, Nagasaki University Hospital, Mitsubishi Boys’ School, Nagasaki Tuberculosis Clinic, Keiho Boys’ High School. Forty thousand people died, and another forty thousand were injured, according to the American government’s postwar estimates. After Hiroshima, now that the bomb was no longer a secret, the Army Air Forces had drafted propaganda leaflets to inform the people of Nagasaki about the possible coming shock—as much an act of psychological warfare as a humanitarian warning. But internal coördination with the bombing crews was so poor that the leaflets were delivered late. They fluttered down over the city the day after the Fat Man went off.

Bockscar circled the mushroom cloud once and then headed for Okinawa, its nearest emergency base. By 1:20 p.m., it was over the island, the crew radioing frantically for permission to land. There was no response. One of the pilots fired a flare gun out of a porthole, to warn all those who could see it that the bomber was coming in, like it or not. The landing was rough but successful. (On touchdown, an engine immediately cut out from lack of fuel.) The crew wired a confirmation message to command, then got some food. They did not make it back to Tinian until 10 p.m. No one was waiting for them. There were no photo ops. Back in the States, even though the bombing was headline news, it shared space with the announcement that the Soviet Union had joined the war effort.

President Truman seems to have been surprised by the second bombing, coming as it did so soon after the first. Intercepted Japanese reports of the damage on the ground at Hiroshima were just trickling in to American officials. Truman, who had written in his diary in late July that “military objectives and soldiers and sailors” were the target of the atomic bomb, “not women and children,” apparently confronted the reality of the weapon for the first time. The Secretary of Commerce, Henry Wallace, reported in his journal that “the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible” for the President. “He didn’t like the idea of killing, as he said, ‘all those kids,’ ” Wallace added.

The day after Nagasaki, Truman issued his first affirmative command regarding the bomb: no more strikes without his express authorization. He never issued the order to drop the bombs, but he did issue the order to stop dropping them. Even if Hiroshima remains preëminent in our historical memory—the first nuclear weapon used in anger—Nagasaki may be of greater consequence in the long run, something more than the second attack. Perhaps it will be the last.

Alex Wellerstein is a historian of science and an assistant professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology, in New Jersey. He runs the blog Restricted Data.

The New Yorker. Fall Sale. Get 12 weeks for $12 $6, plus a free limited-edition tote. Cancel anytime.