The Radical Printmaking of Käthe Kollwitz

In our times, expressionism is often conflated with the movement that succeeded it in the United States — abstract expressionism. Mid-century painters like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko blurred away all traces of realism in a highly expressive, and individualistic, mode of painting that aligned with US propaganda during the Cold War. Decades before drip painting and the Seagram murals hit the American art world, expressionist artists in Europe were concerned with a figurative style capable of responding to war and economic hardship at the turn of the twentieth century.

Among the most prominent of these artists was Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945). Coming of age amid rapid industrialization in Germany, Kollwitz worked across painting, sculpture, and printmaking, helping to give expressionism its radical consciousness.

In lithographs, etchings, and woodcuts, Kollwitz portrayed scenes of poverty and class warfare, devoid of color, using only line and shadow. As a propagandist and educator, she worked with socialist organizations to criticize inequality and oppression under the German Empire, Weimar Republic, and Third Reich. Her monochromatic designs, which appeared on posters and pamphlets, revived an aesthetic form of protest developed during the German Peasants’ War. That she herself produced an iconic print cycle on the sixteenth-century uprising speaks to her sustaining the old cause with the old tools.

Kollwitz was the first woman admitted to the Prussian Academy of Arts. However, her success was cut short when the Nazis banned her work. Dying just sixteen days before Victory in Europe Day, she never saw the ban lifted. Her experience losing children in both world wars led to a preoccupation with motherhood as the first line of defense. From peasant matrons sharpening scythes to mothers leading a weavers’ revolt, Kollwitz’s women subjects transcend their traditional gender roles to rebel against the capitalist order that necessitated their poverty. Despite the many trials she experienced, Kollwitz’s faith in socialism speaks to her sacrifices as a working artist who brought print to a higher plane of social commentary.

Crumbling Empire

Käthe Schmidt was born into a progressive religious family in conservative Prussia. Her maternal grandfather, Julius Rupp, founded the first Free Religious Congregation, and her father, Karl, was a Marxist member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Together, these men influenced her intellectual development. “Father was nearest to me because he had been my guide to socialism,” she wrote to a friend. “But behind that concept stood Rupp, whose traffic was not with humanity, but with God. . . . To this day I do not know whether the power which has inspired my works is something related to religion, or is indeed religion itself.”

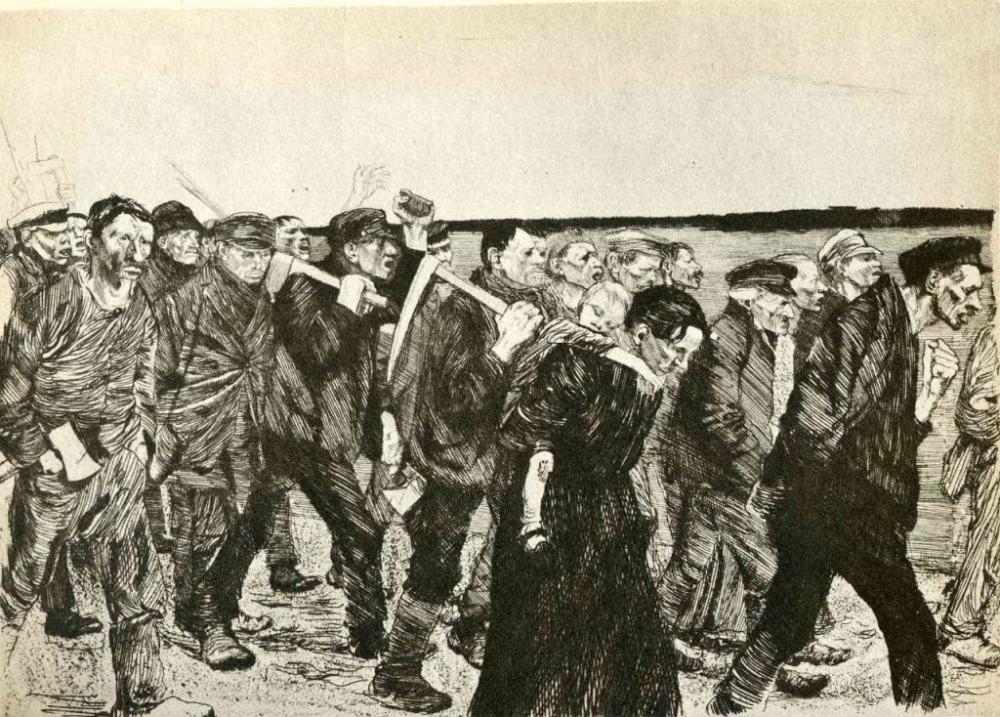

Käthe Kollwitz, “Uprising” (1899). Line etching, drypoint, aquatint, brush etching, sand paper, some roulette. (Wikimedia Commons)

“Little Käthe,” as her family called her, was the fifth of seven children, three of whom died young. Her mother Katharina’s stoicism was formative for Käthe’s early notions of parenthood. The artist was prone to anxiety attacks and suffered from dysmetropsia, or “Alice in Wonderland syndrome,” which distorted her perception of size and self. These early experiences marked her introduction to art-making.

Originally trained in painting, Käthe was drawn to the work of the realist artist Max Liebermann — who painted Germany’s working class — as well as the naturalist literary movement. It was after reading Max Klinger’s essay Painting and Drawing that she delved into printmaking, thanks to Klinger’s championing of the medium and its potential for poetic invention. Her earliest series, monochromatic line etchings adapted from Émile Zola’s 1885 novel Germinal, brought together these influences by depicting a miners’ revolt violently suppressed by the French police and military.

Käthe Kollwitz, “March of the Weavers” (1893–97), sheet 4 of the cycle A Weavers’ Revolt . Line etching and sandpaper. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1891, Käthe married Karl Kollwitz, a doctor and SPD councilman who ran a clinic for Berlin’s working class. Through Karl, she met impoverished mothers and children, who would stay after their appointments to chat with her. Kollwitz soon became a mother herself, giving birth to sons Hans and Peter. Despite the labor of motherhood, Karl worked to ensure that Käthe could sustain an art career while they raised children.

Kollwitz’s first artistic breakthrough came after experiencing Gerhart Hauptmann’s naturalist play The Weavers, which dramatized an 1844 workers’ uprising against poor living conditions and low wages. Her print cycle A Weavers’ Revolt (1893–97) adapts the story across six sheets. The first three provide exposition: a family watches over a dying child in a cramped house filled with weaving looms, leading the father to conspire with fellow workers in a dimly lit barroom. The next two sheets exchange darkness for daylight, showing workers marching with pickaxes and mothers carrying children. In “Storming the Gate,” women lead an attack on a capitalist’s home. Kollwitz juxtaposes their dirty clothing with the lavish gate design, which is overtaken by workers’ hands.

Käthe Kollwitz, “Storming the Gate” (1893-97), sheet 5 of the cycle A Weavers’ Revolt. Line etching and sandpaper. (Wikimedia Commons)

Men carry away dead weavers in the final sheet, revealing subtle Christian themes of martyrdom and suffering. Biographer Martha Kearns notes that A Weavers’ Revolt “transformed” Kollwitz into “an artist who celebrated revolution.” After seeing the work at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, a Prussian awards jury proposed nominating her, but Kaiser Wilhelm II refused. This decision, along with a highly publicized closing of Edvard Munch’s first major exhibition, led Kollwitz and several jury members — including Liebermann — to organize the Berlin Secession. From then through the German Revolution, Kollwitz’s art became inextricably linked with anti-imperialism, leading to further breakthroughs that converged with personal tragedy.

Printing Revolution

The turn of the twentieth century brought Kollwitz to Paris and London, where she studied European art history. While abroad, she created the large-scale etching La Carmagnole, which depicts a scene of French revolutionary women dancing to a battle hymn from Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. That same year, she began her second major print cycle inspired by Wilhelm Zimmermann’s illustrated history of the German Peasants’ War, which Friedrich Engels viewed as the first revolutionary worker uprising of the modern era.

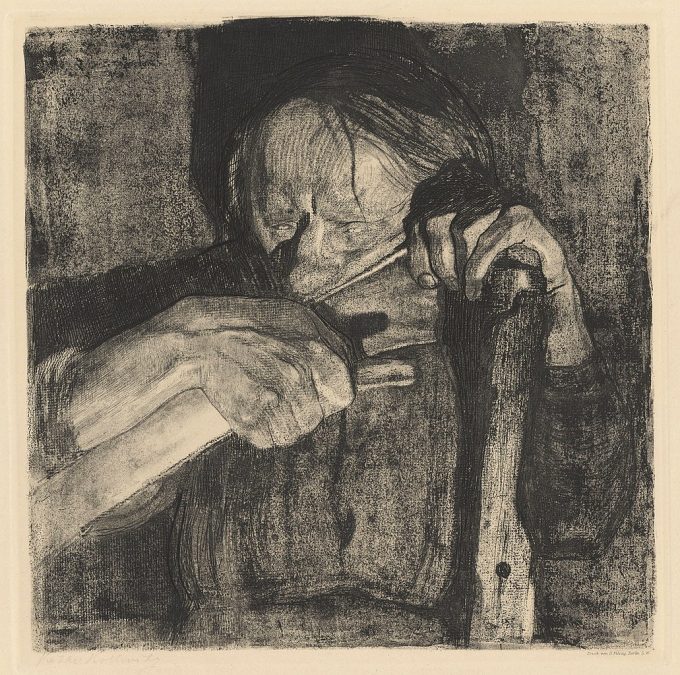

Käthe Kollwitz, “Sharpening the Scythe” (1908), sheet 3 of the cycle Peasants’ War. Line etching, drypoint, sandpaper, aquatint, and soft ground with imprint of laid paper and Ziegler’s transfer paper. (Wikimedia Commons)

The seven screens of Peasants’ War (1901–8) follow a similar narrative to the weavers. Two opening sheets show a plowman bending to the earth and a woman embedded in dirt after being raped. The next frame, “Sharpening the Scythe,” portrays a tense older woman with tired eyes running a whetstone across a long blade. Only two sheets show the actual war, with a sea of peasant warriors fighting night and day, led by a peasant named Black Anna. This is followed by the haunting “Battlefield,” in which an elderly woman makes contact with a young man’s corpse; her veiny hand and his face appear illuminated at the point of contact. The series concludes with survivors tightly packed in an open-air prison.

Peasants’ War was a major success, and Kollwitz’s work was quickly acquired by institutions like the British Museum and New York Public Library. She ensured wide accessibility to her work by producing in high volume and selling at low cost. This meant allowing her work to be reproduced, and, in 1908, she began contributing to Munich satire magazine Simplicissimus, which was committed to publishing visual and literary work critiquing economic inequality.

She also designed propaganda that addressed working-class issues. Her 1906 poster for the Exhibition of German Cottage Industries, showing an exhausted working woman, was so distasteful to Empress Augusta Victoria that she refused to visit. Another for the Greater Berlin Administration Union, which denounced the city’s housing shortage, was banned by an association of landlords.

Käthe Kollwitz, “Battlefield” (1907), sheet 6 of the cycle Peasants’ War. (Wikimedia Commons)

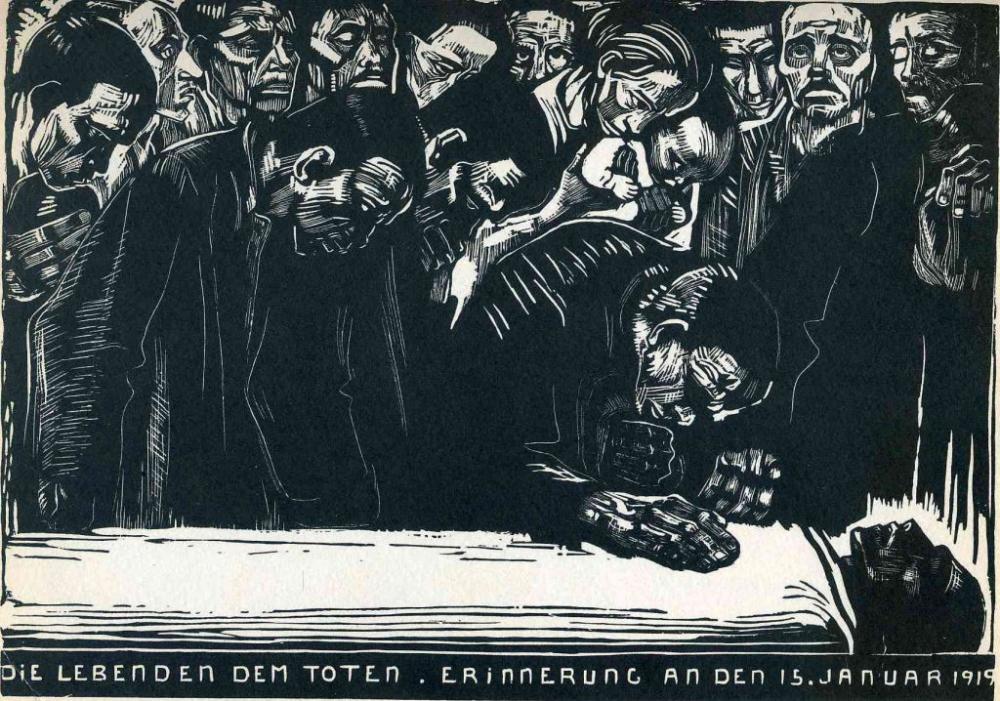

After the assassination of Spartacus League leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg by the Freikorps in 1919, Kollwitz attended Liebknecht’s funeral with thousands of supporters and became sympathetic to the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, or KPD). Her memorial to Liebknecht is one of the results of that experience. It shows his pale corpse lying flat in the style of a Christian lamentation, surrounded by black-clad mourners. His side profile appears to glow, emanating bright streaks into the coat of a sobbing man who seems not to notice.

Radical Motherhood

In 1913, Kollwitz cofounded the Organization of Women Artists, coinciding with her foray into sculpture. One year later, and just three months into World War I, her son Peter was killed in action. This sent the artist, who spoke with so many ailing mothers, into a deep melancholy that informed the remainder of her career. While working in a cafeteria for the unemployed, she experienced a long period of creative stagnation that lasted until the revolution.

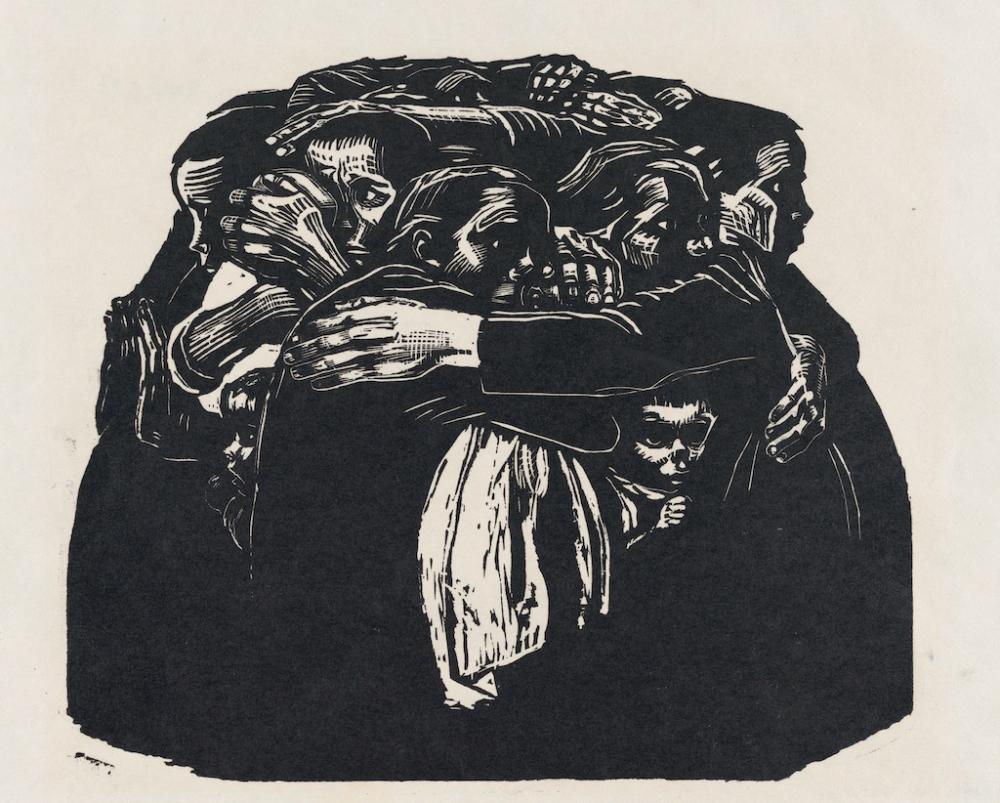

As poet Richard Dehmel urged further action in the war, Kollwitz published a dissenting letter in the German press that quoted Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: “Seeds for sowing should not be ground.” Following armistice, her woodcut series The War (1918–1923) provided a searing critique of the conflict’s effects on family life. One sheet, simply titled “The Mothers,” shows a group of women holding each other as one. This piece, which looks almost sculptural, became the archetype for her many sculptures of mothers protecting children, and an enlarged version is prominently displayed at the Central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany to the Victims of War and Tyranny in Berlin.

Käthe Kollwitz, “The Mothers” (1921-22), sheet 6 of the series The War. Woodcut. (Wikimedia Commons)

The peak of Kollwitz’s career came in 1927 with recognition by the Weimar Republic. She visited the Soviet Union with Karl to commemorate ten years since the October Revolution and became the head of the Master Studio for Graphic Arts at the Prussian Academy, but her tenure was short-lived. When the National Socialists came to power, Kollwitz signed an appeal with Karl, Heinrich Mann, Albert Einstein, and other intellectuals to align the SPD and KPD against the National Socialists, followed by a second attempt led primarily by Mann and Kollwitz in 1933.

Coverage in a Moscow newspaper led the Gestapo to question Kollwitz and threaten imprisonment, and eventually led to the removal of her work from German museums and her forced resignation from the academy. The Nazis stored her art in the basement of the Crown Prince’s Palace throughout World War II, claiming that “mothers have no need to defend their children. The State does that.”

A Clear Political Message

Some critics have argued that Kollwitz’s work was not political because she never portrayed the oppressor. Others have alleged that her style was “out of touch” during the birth of abstract expressionism. For Louis Marchesano, this notion is a result of the “aesthetic purification” that took place during the Cold War in North American and West German cultural institutions.

Käthe Kollwitz, “In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht” (1920). Woodcut. (Wikimedia Commons)

But Kollwitz’s art, grounded in her radical commitments, and with its representations of working-class history, was deeply political. She aligned herself with many of the largest democratic and anti-war organizations. She was a member of the communist-led Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom as well as the Workers’ International Relief. She designed posters for the International Labour Union, and her “Never Again War” illustration for the Central German Convention of Young Socialist Workers became an icon of the anti-war movement after her death.

Kollwitz embraced negative space, wielding shadow to define her scenes before expressionist filmmakers popularized this aesthetic. The darkness of daily life took its toll on her, but optimism persisted. This is evident in one of her last letters, to her daughter-in-law Ottilie, in 1944:

Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed. The devil only knows what the world, what Germany will look like then. That is why I am whole-heartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism.

Billy Anania is an art critic, editor, and journalist in New York City.

Subscribe to Jacobin today, get four beautiful editions a year, and help us build a real, socialist alternative to billionaire media.