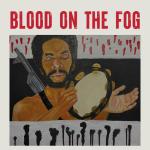

Blood on the Fog

Blood on the Fog

Pocket Poets Series No. 62

Tongo Eisen-Martin

City Lights Books

ISBN-13: 9780872868755

Thirty minutes into a 75-minute conversation with Tongo Eisen-Martin about revolution, reading and writing poetry, and becoming—in January 2021—San Francisco’s 8th Poet Laureate, he spontaneously comes up with a gem: a one-paragraph summary of his family history and his life and work up to today that in the last sentence says everything.

“The first advantage I had, as a future writer, was being around people who put together an intentional village,” he says. “I was raised not just with a revolutionary mother, but at the freedom school, Meadows Livingstone. I’m going to the African American Arts and Culture Complex—called the Western Addition cultural center when I was a kid—every day. I’m going to the Larkin Black dojo where they trained Black Panthers. My mother is taking me to plays in Dolores Park, my godmother is painting murals on 24th Street. I’m around people whose imaginations are super kinetic. I’m in an area and a city where people’s imaginations are more confident and less likely to buckle in the face of white-supremacist culture and capitalist identity as it dominates other parts of the United States. My imagination was growing up imitating the structures of these imaginations or this mandate that says, yes, you are supposed to create reality just as much as any other force. That gives me more dimension or maybe a double-jointedness of sorts.”

Double-jointedness is a terrific way to describe Eisen-Martin’s poetry and literary practices. Especially in his most recent collection, Blood on the Fog (City Lights Books), the 39 poems dedicated to his mother, Arlene Eisen, arrive with mind-bending, multi-directional force: blistering heat, visceral energy, judicious reserve, gentleness, humor, lucidity and more.

Eisen-Martin grew up in a neighborhood, near 25th and Valencia, in San Francisco’s Mission District. He earned a master’s from Columbia University. While teaching at Columbia’s Institute for Research in African-American Studies and writing under the umbrella of Operation Ghetto Storm, a website/organization founded by his mother that is dedicated to reporting on the extrajudicial killing of Black people by police, Eisen-Martin created We Charge Genocide Again! This curriculum provides instruction in critical thinking and analysis of state-sanctioned killings for teacher-students and student-teachers. The curriculum has been taught and/or used nationwide in classrooms, community programs and in detention centers—including San Quentin and Rikers Island. Eisen-Martin is cofounder, with Alie Jones, of Black Freighter Press, a publisher and “platform for Black and Brown writers to honor ancestry and propel radical imagination,” as stated on Black Freighter’s home page.

Eisen-Martin is the author of Someone’s Dead Already (Bootstrap Press, 2015), which was nominated for a California Book Award, and Heaven Is All Goodbyes (City Lights Books, 2017), which received the 2018 California Book Award for poetry, a 2018 American Book Award and was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize. His poems have been published in Harper’s Magazine, the New York Times Magazine and elsewhere.

All of which means that in addition to his poems, words spoken during an interview display the aforementioned double-jointedness. Part improvisational genius and skilled spoken-word artist, part living mantra due to his daily meditation practice, part scholar, performer, educator, activist, revolutionary and poet dancing aloud on the edge of his own consciousness—Eisen-Martin’s many parts amalgamate most vulnerably and without pretense in response to an invitation to speak about what is most true of his poems. “Some people got me down when they analyze my work,” he says. “I’m pretty see-through. What’s not emphasized enough is your journey before you pick up the pen. That determines everything. There’s no way I would have poems of worthy political insight if I had not spent years and years as a teacher and organizer. I had a knack for language, but nowhere near the levels of experiment without having a dedicated meditation practice. Without all that work that happens before I pick up the pen, nothing is possible.”

The enormity of the task might knock over a less-stable ego. Humility and practicality factor into his balanced equilibrium. “It’s just homework,” he says. “You try to do right by this human thing and the homework makes it a worthwhile contribution to a conversation.” Hesitating to codify the mathematics of poetry, he steers away from losing his mind on assertions of the quantum rules of words. “What I have a feeling of are shapes to phenomenon, to definition, or structures of energy that you do best to conform to. Even within yourself as you’re giving thought to an energy, if you don’t overreach or get too ambitious and let words decorate or trace the shapes of the energy, you have something musical that happens. That’s what I’ve been mulling over lately.”

But there are combinations of words that just have a ring to them, right? Yes, he answers, just as there are intellects that are charismatic. “Like historian Gerald Horn; his writing reminded me of Thelonious Monk,” he says. “I experience Horn in the same way. He’s output-heavy because he’s making a clear point, but he just has this knack. He has a mind with access to information that’s supernatural, and at the same time he has humorous structures that almost feel good to say. He’s talking about horrific stuff, but there’s a humorous architecture to his work.”

The architecture of Eisen-Martin’s “Factory of Wrists,” one of the poems in the new collection, erected itself in May of 2020. “This poem I wrote the next day after George Floyd was killed. This is me exasperated. I was at the end. I was analyzing social contradictions of race in a genocidal society and a war machine. We’re here in a reality absolutely produced by a monopoly of violence. There’s a shift, within ‘Factory of Wrists,’ to a call to a future leader—but it began with the energy of the execution in the streets.”

“Two Sides Fight” began with the title and ideas relating to natural social contradiction. “We start on one land and then move to analysis,” Eisen-Martin says. “We’re a comedy just as much as some country in the so-called ‘Third World.’ It’s a scene from a domestic comedy, through the lens of an artist or writer—a colonized writer or an oppressed writer alienated from themselves. Here is a mind suffering from internalized oppression. The God lines are about how I’m not a craft that’s moving in truth, even within the sarcasm. Do I wonder that about myself all the time? I do. In a way, that’s almost a luxury of being born in an oppressed period of society. You can get energy and insight from just turning away from your oppression. It’s not like I’m even achieving enlightenment—but I can just take a step away, and there’s all kinds of potential available. Even in a political critique, you operate from honesty but also from internal experience. In an existential way, I fear for my poetry. But this fear is another tool in my tool box.”

Eisen-Martin says “I Make Promises Before I Dream” is one of his favorite poems he does not know by heart—a rarity. Typically, he writes slowly and stays on top of his poems. “Also, I’ll go through a poem and it will have three phases of development. By the time I’m done, I’m familiar with it,” he says. “Some poems in Blood on the Fog were literally written, or the ideas sketched, right after my second book. I ended up almost not knowing where to go with them. There was an evolution in my approach to writing that rescued those poems.” Asked how his work changed during that evolution, he says daily insights are faint, but he perceives stark differences over broad timeframes and retroactively recognizes shifts in his consciousness. “It’s like looking at a past life,” he says. “All of my poems in the last 7 to 8 years have existed in this one effort that’s tied to a lucidity of craft and a quest for lucidity. Wherever they move in their orbits, the poems have never gone far from that effort.”

Recalling opening his mind and energy to “whatever happened in two hours,” he says the then-novel approach used to write “I Make Promises” resulted from an overwhelming, discombobulated day. “It was a different writing assignment for the Museum of the African Diaspora, when they actually wanted a new poem on an actual exhibit, and I thought it was just a regular reading of my poems,” he says. “They wanted it the next day. I put on a Coltrane album and listened to a song titled ‘Out of This World.’ Between that and the art, I was filled with energy I usually try to turn down. It paid dividends, because learning to dance without euphoria made it so much more alive. I learned to do this thing that’s ‘drop the story and internal chatter and put attention to listening in realtime to sensations going through your body.’ That works in real life and when responding to stuff that’s painful or heavy. You stop everything and put your attention on physical sensation, and the overwhelming emotion just dissipates, and what’s left is beautifully cooperative energy. Usually the subconscious voices seem like chatter, but when you distract the evaluator with this task of minding the energy you come up with interesting rhythms because you’re not conspiratorial in that floor of your mind. ‘I Make Promises’ was one of my first poems using this way to write.”

Rounding the corner of the conversation to land on revolution, Eisen-Martin admits his revolutionary practices are “at a low tide.” Day-in, day-out immersion in movements aimed at seizing production from the ruling class and dismantling their structures of apparatus, armies and prisons, he suggests, must be scaffolded with generations of people holding pronounced tasks. “I’m old-school,” he says. “We’re tasked with a punctual project; one that’s dedicated to transforming consciousness, more than a commitment to action. That counters how movement is viewed these days.” Longtime divisiveness, he suggests, has caused many people to lose steam.

The solution? “We take a half-step and rewind back to the idea of cultural work. We haven’t gone deep enough into the social contradictions in this society, especially the contradiction between Black people and and the white power structures,” he says. “Evaluate whiteness more as a deputization than a privilege. Look at the generator of reality being organizational violence from day one. Then the resulting analogy, using it as a lens for analyzing the way we relate to each other, is crucial. That’s why my foot is on the gas so much in my books. I want to get to the bottom of whiteness, of the United States’ ruling class, the cop that lives in your head, the theater of the oppressed, in order to synthesize revolutionary programs that will actually be sure-footed.”

While alternately issuing words born of a red-hot collective roaster or pulling back to breathe through inner spaciousness, Eisen-Martin says it is premature to predict if the visibility of his poet-laureate platform will be advantageous—or if the blistering honesty of his poetry and activism will cause discomfort. Besides, there is one far more important concern. “I don’t assign anxiety to that question, because I evaluate myself by my revolutionary practices,” he says. “I don’t underestimate poetry and its potentials, but I know I’m healthy when my practice is strong. As long as my revolutionary practice is strong, how things play out for me individually doesn’t really matter.”