A 1980s Blueprint on How to Be a Leader - Chicago's Harold Washington

Stepping into office after winning a tough race, he knew that getting his agenda passed would be difficult due to stiff opposition in the legislative branch. He eventually won lawmakers over with a massive infrastructure package that he figured correctly would be difficult to vote against since it benefitted his opponents’ own constituents.

Not Joe Biden. He did that too, but Harold Washington, the first Black mayor of Chicago, did it first.

Washington’s historic early 1980s run to become Chicago’s 51st mayor set a blueprint for progressive politicians looking to lead in a time of intensifying partisanship and segregation. His first term as mayor, from 1983 to 1987 was a masterclass in how to govern in the face of political obstructionism, lessons that could be applied in similar political struggles happening today.

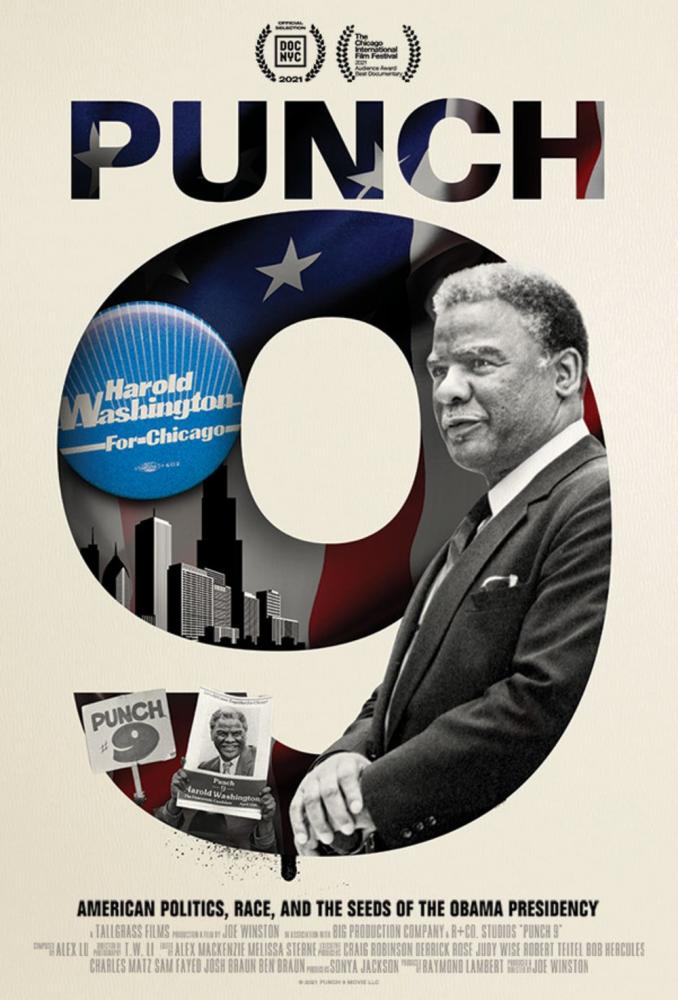

Those lessons have been assembled for the new Joe Winston-directed documentary “Punch 9 for Harold Washington,” which premiered at film festivals in Chicago and New York last year. The 90-minute film examines Washington’s unlikely ascent from one of Black Chicago’s prominent political leaders to mayor of the entire city. After successfully winning the mayoral race in 1983, Washington was immediately stiff-armed by political opponents in the city council whose top priority became, as one white alderman in the film said, “making Washington a one-term mayor.”

Republican U.S. Senate leader Mitch McConnell would express an almost verbatim sentiment a few decades later about Barack Obama (Washington’s political progeny) when he was elected president in 2008. McConnell also said as much this year when Biden, Obama’s former vice president, was elected to the White House. How Biden is responding to Republican defiance rings eerily close to Washington’s approach in the 1980s: through infrastructure and voting rights.

Washington wasn’t up against Republicans; he was facing members of his own Democratic Party who didn't back his mayoral campaign, even after he defeated challengers Richard M. Daley, the son of the former mayor Richard J. Daley, and the incumbent Mayor Jane Byrne in the primary. Instead, they rallied their constituents to back Washington’s opponent in the general election, the Republican Bernard Epton, who came up just 40,000 votes short of defeating Washington.

Unsuccessful, Democrats tried to neutralize Washington via city council, where 29 of the 50 alderman districts formed an impenetrable voting bloc of Democrats representing the local party machine. Led by Cook County Alderman Edward Vrdolyak, the group launched what’s been called “Council Wars,” vowing to vote down any legislation promoting Washington’s agenda.

Washington campaigned on distributing city resources more fairly across the city, to reverse the long history of services and investments flowing almost exclusively to white and wealthy districts. That task was made nearly impossible when Washington was stopped not only by obstruction from the bloc that came to be known as “Vrdolyak 29,” but also by President Ronald Reagan’s massive cuts to federal social safety nets and funding streams for cities.

The effect of both forces led to pressure for Mayor Washington to raise taxes — an unpopular entreaty that often guarantees mayors won’t get a second term. Chicago was suffering an economic malaise as manufacturing warehouses and steel mills were closing, many of them in predominantly white neighborhoods. This meant that white unemployment was now shooting up in ways previously only seen among Black people in Chicago. It was the new Black mayor’s problem to solve, but Washington’s opponents claimed that he would only make their situation worse.

“It was, ‘Wait, the Black mayor is going to do to us, the white community, what the white community did to the Black community all those years,’” says Gary Rivlin, a reporter for the Chicago Reader at the time and author of the 2012 Washington biography Fire on the Prairie. The Black community “is going to get disproportionately more city services, their parks will be improved, they’ll have better garbage pickup and ours will suffer — that was [white Chicago’s] big fear. The Vrdolyak 29 played into that fear.”

After months of stonewalling, Washington came up with an offer that his opponents couldn’t refuse: a massive capital improvements package. To sell it, he did a press tour of his enemies’ districts, pointing news cameras toward the potholes, sinkholes, broken curbs and malfunctioning sewers that had been in a state of disrepair for decades. Washington requested the city issue an $85 million bond — the biggest bond issue in the nation’s history at the time, according to his then-deputy press secretary Laura Washington — to pay for it.

The junket made Washington’s infrastructure proposal popular among voters; meanwhile, the Vrdolyak 29 bloc, which initially rejected the bond issue, became increasingly unpopular. The residents of the districts where the repairs were needed began demanding that Washington’s infrastructure proposal get passed, which forced the aldermen to cave and eventually vote for it.

“That’s when the tide turned,” says Rivlin. Instead of opposing the bond, the aldermen began criticizing the amount as too small, saying they wanted more for their wards. “The fight became: How big is the thing going to be? Which, of course, means at that point that Washington won.”

However, this essentially rewarded Washington’s opponents by showering their districts with new infrastructure remodeling and upgrades, which some Black community activists initially took umbrage with. But the bond covered improvements for the whole city, meaning Black neighborhoods benefitted as well. Washington remained popular despite the spoils of this victory getting shared with the white alderman who were hostile to him.

“African American voters are diplomatically astute and observant, especially in a city like Chicago,” Laura Washington, who isn’t related to the former mayor, told CityLab. “They understood what needed to be done and they understood that Harold Washington wouldn't be able to accomplish much if he didn't at least make an effort to be fair to everyone and it'd be equitable to everyone. His messaging was always: We just want fairness.”

But the only way Washington was going to govern effectively was with more allies in city council. For that, he needed the Voting Rights Act, which he had just helped get reauthorized as a congressional House member prior to becoming mayor. One of the provisions of that law states that voting districts can’t be drawn such that people of color are unable to elect a candidate of their choice, particularly when the candidate shares the race of the minority voter.

In Chicago, despite an exploding Latino population, which climbed from 329,900 in 1970 to 579,900 in 1980, Latinos had no representatives in city council. They were a little over 8% of the city’s population but had no aldermen.

In Chicago, despite an exploding Latino population, which climbed from 329,900 in 1970 to 579,900 in 1980, Latinos had no representatives in city council. They were a little over 8% of the city’s population but had no aldermen.

So, Mayor Washington filed a Voting Rights Act complaint, which led to the redrawing of districts in Chicago’s growing Latino and Black neighborhoods. Under the new maps, two Latino aldermen were elected in a special 1986 election, as well as two more Black aldermen. That split city council in half with the “Vrdolyak 29” reduced to 25. Washington would be the deciding vote in the event of a tie.

“We were one of the first cases because the Voting Rights Act had just been amended,” says Judson Miner, the city’s attorney under Washington who helped file the complaint. After that “you started seeing them everywhere.”

Washington’s career as mayor was shortened — he died of a heart attack shortly after getting re-elected in 1987. But the legacy he left behind serves as a manual for politicians and elected officials of color on how to prevail against a predominantly white establishment.

It’s also a playbook that looks similar to one being used by President Biden today. Biden was able to circumvent the congressional blockade looking to make him a one-term president by passing a $1 trillion infrastructure bill in November, similar to what Washington did. So far, though, Biden has failed to win congressional support for his larger Build Back Better bill, which focuses on social infrastructure and safety nets.

Like Washington, he may need help from new voting rights legislation to win more allies in Congress. The Democrats have several bills currently blocked by Republicans in Congress that would strengthen the Voting Rights Act, to give further protection to voters in cities and states across the U.S.

Republicans say the new rules would invite voter fraud — despite research showing otherwise — and have rejected allowing any debate on new voting rights legislation. The 1980s amendments to the Voting Rights Act — adopted when Washington served in Congress and then used to win fairer city council maps for Chicago — have been weakened by several U.S. Supreme Court rulings in recent years. It’s the kind of political entanglement that may leave today’s Democrats asking: What Would Harold Washington do?

[Brentin Mock is a writer and editor for CityLab in Pittsburgh, focused on issues of racial equity, economic inequities, and environment/climate justice.]