The Radical Vision of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes

The cost of labor rights in the United States has always been paid in workers’ blood. Many of the labor movement’s most critical moments are scented with gunpowder and dynamite and punctuated by funerals. Many of the movement’s greatest heroes have been beaten or imprisoned, and cops and assassins have murdered rank-and-file leaders like IWW organizer Frank Little, strike balladeer Ella May Wiggins, Laborers head Joseph Caleb, United Farmworkers strike leader Nagi Daifullah, and United Mineworkers reformer Jock Yablonski. But even against that backdrop, the story of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes sounds more like a 1980s action movie than the real, horrific tragedy that it was. In 1981, a foreign despot organized the gangland execution of two young Filipino union organizers, with guns furnished by their own union president.

Domingo and Viernes are especially relevant now, as thousands of rank-and-file union members across the country are challenging the entrenched power structures and sclerotic union leadership whose actions—or lack thereof—have been disempowering members and weakening the broader labor movement for decades. In December 2021, over 60 percent of the membership of the United Auto Workers (UAW), one of the nation’s most storied unions, voted to implement a system of direct elections, thus upending the decades-long top-down rule of the UAW’s Administration Caucus. The referendum was the result of a consent decree between the union and the US Department of Justice, and followed a federal corruption probe and years of corruption charges against various high-ranking UAW officials, including former UAW presidents Gary Jones and Dennis Williams. Led by the Unite All Workers for Democracy reform committee, the “one member, one vote” campaign captured the attention of both the members (143,000 of whom voted) and the labor movement as a whole.

These are all fights over union democracy—a condition in which members have a direct say in their representation and the running of their union. Last year, the Teamsters for a Democratic Union notched a major victory when members voted overwhelmingly for a progressive, militant Teamsters United slate, toppling the Hoffa dynasty. The TDU was founded in the 1970s (initially as Teamsters for a Decent Contract) to push for free and fair elections. After a sprawling federal racketeering case against the union led to a 1989 consent decree forcing the union to implement “direct rank-and-file voting by secret ballot in union-wide, one-member, one-vote elections,” TDU was able to start cleaning up the union, and even briefly seized power before Jimmy Hoffa’s old guard came crashing back in in 1998. Now, the reformers have another chance to restore the union to its fighting form, and trade concessions and sweetheart contracts for beefed-up representation. TDU promises to modernize operations, bring Amazon to heel, and build enough power to face down UPS at the bargaining table in 2023.

Domingo and Viernes would surely have been thrilled to hear about these developments. They too were elected to leadership on a reform platform, and were determined to root out the corruption within their union, Local 37 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), which until 1950 had been a local of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse, and Allied Workers of America, and before that, the Cannery and Farm Labor Union (CFLU) Local 18257. (In a stroke of foreshadowing, two Filipino CFLU leaders, Aurelio Simon and Virgil Duyungan—himself accused of corruption—were murdered in 1936 after fighting to abolish the exploitative contract labor system that kept Asian immigrant cannery workers in a cycle of debt and poverty. However controversial they may have been in life, their deaths galvanized the Filipino cannery worker community and strengthened the union.)

When Domingo and Viernes ventured into the Alaskan canneries in the 1970s, they were building upon decades of organizing, educating, and agitating by Filipino and Native Alaskan labor organizers and rank-and-file workers. The two friends—one an unassuming Texan, the other fond of driving a flashy Monte Carlo, both dedicated revolutionaries—spearheaded efforts to improve working conditions in the cold, wet factories full of sharp knives and fish guts where thousands of seasonal Filipino migrant workers (“Alaskeros”) and Native Alaskans labored. They were no strangers to the slime line; Viernes grew up spending his summers working in the Alaskan canneries, and Domingo had Alaskero experience as well; his father, Nemesio, a former migrant worker, was also the vice president of Local 37. As Viernes wrote in his unfinished history of the Alaskeros, “When the spring field work comes to a grinding halt, many Filipino workers migrate north to find the one job available to them: sliming fish in the chilly fish houses of Alaska.… they have tried but cannot find work elsewhere, lack necessary skills, schooling, or resources, and are prevented from gaining jobs.”

White employers treated Filipino workers and Native Alaskans abominably. The Filipino workers were kept in segregated, dank bunkhouses and served fish-head soup to power their 12-hour shifts. These migrant workers were part of a seasonal loop that took them from California’s fields to Washington’s fruit orchards to Alaskan canneries, and back again. One of the few upsides of this arrangement was that these workers also carried their shared grievances and union sympathies with them. When union organizers showed up, they were often welcomed with open arms by workers fed up with the racism, discrimination, and brutal working conditions. In 1971, Domingo and Viernes both found themselves blacklisted from their cannery jobs for speaking up about racism and soon became involved in the Alaskan Cannery Workers Association, which brought three class-action lawsuits against the cannery companies for racial discrimination. That would mark the beginning of their brief but historic partnership, and showed how their experience as rank-and-file workers drove them to try to fix the union they still believed in.

Inspired by Local 37’s militancy in the 1930s and ’40s (when the contract labor system was finally thrown off for good) and dispirited by its post–Red Scare conservatism, the two young men resolved to reform the organization from the inside. They founded a rank-and-file committee in 1977 devoted to fighting for union democracy and against corruption, which was already widespread. The union’s dispatch system, which determined which workers would be sent out to work assignments and was supposed to operate around seniority, was instead controlled by dispatchers and foremen who gave the best gigs to their gambling buddies and those who could afford a bribe. The union’s cozy relationship with organized crime further complicated matters; often those jumping the line were Tulisan gang members, who paid their way into the canneries where they oversaw gambling operations. Trying to clean up the union was dangerous, but the Rank-and-File Caucus persevered, quietly organizing across racial lines, training shop stewards, and building power for several years until they swept the 1980 elections and installed Domingo as secretary-treasurer and Viernes as a dispatcher.

The pair were also deeply involved in the Filipino community in their adopted hometown of Seattle, and were local leaders in the anti-imperialist struggle against the US colonial control of the Philippines and the country’s kleptocratic dictator, Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda. Domingo and Viernes cofounded in the Seattle chapter of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, or KDP), a revolutionary anti-imperialist socialist organization devoted to combating Marco’s antidemocratic repression. They worked to foster solidarity across the Filipino diaspora and to inspire their local community to speak out against the atrocities happening back in the Philippines. In 1981, Viernes took a trip to the Philippines to visit family, meet with anti-Marcos union leaders (and present them with a $290,000 donation), and learn about the struggles workers faced under the Marcos regime. His findings were far from positive, and several months later, at an ILWU convention in Honolulu, he and Domingo introduced a resolution to investigate the conditions of workers in the Philippines (to the dismay of the Marcos supporters within their ranks, which included Local 37 president Tony Baruso).

Their resolution passed, but those close to them say that the convention was the moment when Domingo and Viernes knew that their futures were in jeopardy. Terri Mast, a Rank-and-File Caucus member, KDP comrade, and Domingo’s partner, with whom he was raising two young daughters, characterized their resolution as “a direct threat” to the Marcos regime, which had little support from labor due to its inhumane treatment of workers. “The support for the KMU, the largest trade union federation in the Philippines, had just been sealed,” she told Ron Chew in his essential oral history, Remembering Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes The Legacy of Filipino American Labor Activism. “Any disruptions of cargo in or out of the Philippines would have a major economic impact on the country.” Between the resolution, and Viernes’s overseas trip and material support for the anti-Marcos labor movement, the men were not surprised when they began seeing unfamiliar cars tailing them and their family members. After the convention, Domingo came to the Local 37 board with a macabre request: He wanted to buy life insurance.

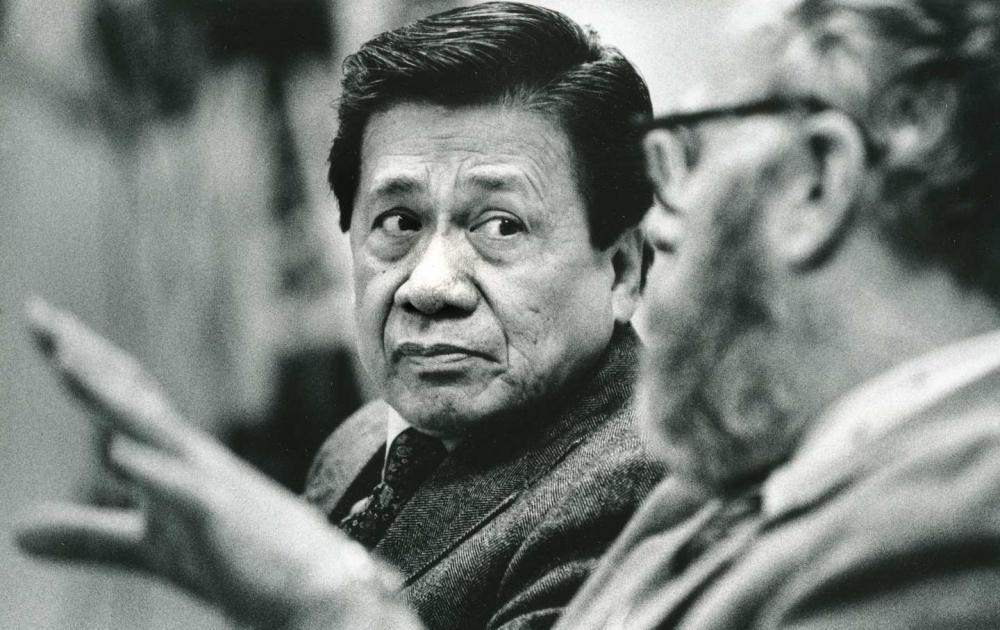

Tony Baruso listens to his defense attorney, Tony Savage, in court in Seattle. Baruso died in prison while serving a life sentence for the murder of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes. (Grant M. Haller / Seattle Post-Intelligencer / Associated Press)

His instincts were correct. On June 1, 1981, two Tulisan members murdered Domingo and Viernes, who were both only 29 years old. Viernes died immediately, but Domingo, shot four times in the stomach, dragged himself outside and gasped out the names of the men who’d shot them. He died the next day, and the men he’d named—“Guloy and Ramil,” or Pompeyo Benito Guloy and Jimmy Bulosan Ramil, Local 37 members and Tulisan enforcers—were arrested for murder and sentenced to life in prison, as was gang leader Tony Dictado, who’d put out the hit and driven the getaway car. The police questioned Baruso, but he would not face charges until a decade later. According to Seattle attorney Michael Withey, a close friend of Domingo and Viernes who had been the lawyer for ILWU Local 37 in 1981 and wrote a book about the murders, “The FBI was instrumental in the cover-up and didn’t want Baruso charged by the prosecuting attorney.” In 1991, Baruso—whom Withey contends the Marcos regime paid $15,000 to orchestrate the murders—was finally found guilty of first-degree murder and ordered to pay millions to the victims’ families. He died in prison in 2008.

As the Domingo and Viernes’s families and community mourned, it soon became clear that the shooters had been bit players in a larger conspiracy. “I would say it took us less than 48 hours to really map out who benefitted from the murders, and it was always the Marcos dictatorship who benefitted from Silme and Gene’s murders,” Cindy Domingo, Silme’s younger sister, told Seattle’s KNKX in 2020. The loss of Domingo and Viernes was devastating, but their surviving family members and labor comrades continued the work they’d begun together. Mast and Cindy Domingo worked alongside dozens of activists to create the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Viernes, whose legal work would connect the murders directly to Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. The Marcos were found guilty by a federal jury in 1989. It was the first and only time a foreign head of state has been held responsible for the deaths of Americans on US soil.

It’s hard to believe that a story this full of drama, violence, justice, and heartbreak isn’t common knowledge (or an HBO series), but Domingo and Viernes, like so many other pivotal labor leaders, have never gotten as much recognition as they deserve. Their memories loom large within several spheres, though—in Seattle’s Filipino and labor communities, in the ILWU’s storied history, and in the history of trailblazing rank-and-file Asian immigrant worker leaders in the US labor movement. Using court-ordered funds awarded from both the Marcos family and the four convicted murderers, Seattle’s Northwest Labor and Employment Law Office created the Domingo/Viernes Justice Fund in their memory. The Harry Bridges Labor Center at the University of Washington offers an annual Silme Domingo & Gene Viernes Scholarship in Labor Studies to students “who are committed to the principles of justice and equality and have demonstrated financial need.” Though devastated by the loss, Rank-and-File Caucus continued its reform mission, entering a troubled period before finding new footing in a merger with the Inlandboatmans Union. Mast, the lifelong labor activist and Domingo’s common-law widow, stepped in to fill his position in Local 37 after his death, and has served as the IBU’s secretary-treasurer since 1993.

Silme’s daughter, Ligaya Domingo, was only 3 years old when her father was murdered, but has kept his memory alive in her own way. She began her career in labor as a union organizer, and she now works as the racial justice and education director at SEIU Healthcare 1199NW. “I was just really instilled with the idea of needing to do work that changed the world,” she told Ron Chew in his oral history. “Working in the labor movement in a lot of ways is like home to me, because I’m with people who understand me on this whole new level because they know my history.”

Copyright c 2022 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Kim Kelly is a writer and labor activist based in Philadelphia. She is the author of FIGHT LIKE HELL: The Untold History of American Labor.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for as little as $2 a month!