The Extreme Bias of Florida’s New Congressional Map

Coming soon to a 2024 Republican presidential primary ad near you: Gov. Ron DeSantis stood up to moderate Republicans who wanted to appease liberal Democrats, and he won.

On Thursday, the Florida Legislature finally caved to DeSantis’s wishes and passed one of his proposed congressional maps — the last major piece in the national redistricting puzzle. And befitting DeSantis’s national reputation (and ambitions), it is a dream map for partisan Republicans, single-handedly adding four new Republicans to the U.S. House of Representatives. But while DeSantis’s uncompromising insistence on maximizing Republican power may give him a nice story to tell if he runs for president, it could also be the map’s undoing in court.

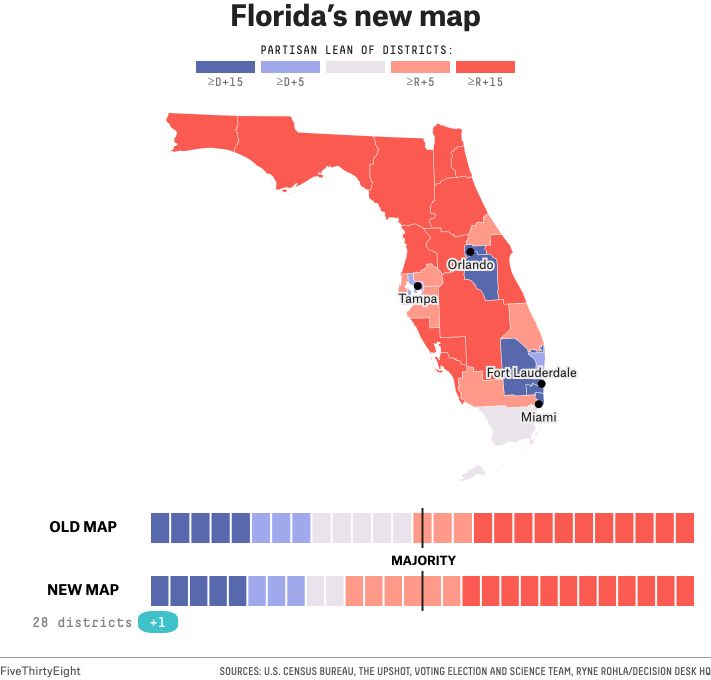

Florida’s soon-to-be congressional map (it will go into effect once DeSantis signs it) creates 18 seats with a FiveThirtyEight partisan lean1 of R+5 or redder and only eight seats with a partisan lean of D+5 or bluer. (The remaining two seats fall into the “highly competitive” category between R+5 and D+5.)

This map will significantly shake up Florida’s congressional delegation, as it virtually guarantees that Democrats will lose three of their House seats in Florida: The 7th District goes from a D+5 partisan lean to R+14, the 13th District now has a partisan lean of R+12, and Rep. Al Lawson’s North Florida district is completely refigured into a solidly Republican seat. In addition, the new congressional seat that Florida gained from the 2020 census — numbered the 18th — is dark red under this map, for a GOP gain of four seats in total.

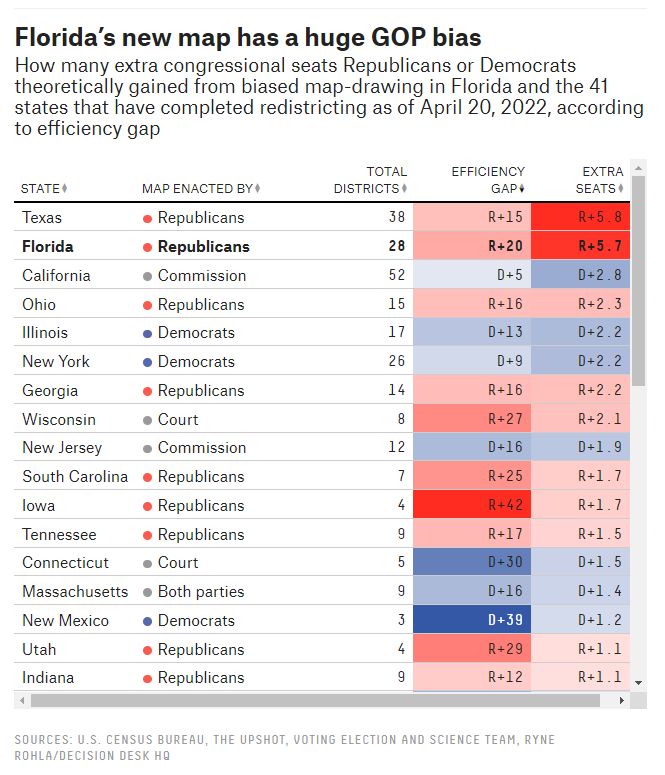

This is about as big of a Republican bias that Florida’s congressional map could have — and darn close to the most egregiously partisan map in the country. The map has an efficiency gap of R+20, which means Republicans would be expected to win 20 percent more seats under this map than under a hypothetical, perfectly fair map. Because Florida has 28 congressional seats, that translates to a 5.7-seat Republican bias — right on Texas’s heels for the “honor” of having the biggest bias of any state.

Florida’s new map has a huge GOP bias

How many extra congressional seats Republicans or Democrats theoretically gained from biased map-drawing in Florida and the 41 states that have completed redistricting as of April 20, 2022, according to efficiency gap

But it didn’t have to be this way. Republicans in the Legislature initially passed maps that were significantly less biased. The state House passed a map in March that would have created 15 seats that were R+5 or redder and had an R+13 efficiency gap (though according to the inventors of efficiency gap, that would still qualify as gerrymandered). And in January, the state Senate passed a map that was close enough to fair (an efficiency gap of only R+6) that even most Democratic senators voted for it.

But DeSantis pledged to veto them both, insisting that only one of his uber-aggressive proposals would do. His beef, at least publicly, was that the Legislature’s proposals preserved (in some form or another) Lawson’s blue district, whose old iteration stretched from Tallahassee to Jacksonville in order to pick up enough Black voters to give them a voice in Congress. Ironically, DeSantis claimed this violated the 14th Amendment by prioritizing race as the main consideration in drawing the district over other factors like compactness.

At first, Republican legislators brushed off DeSantis’s objections. They argued that the “Fair Districts” amendment to the Florida Constitution — a redistricting reform that voters passed in 2010 — required the preservation of a predominantly Black seat in North Florida. And, already miffed over DeSantis’s strong-arm tactics on redistricting and other issues, they firmly pushed back against his maps and his legal arguments.

After DeSantis issued his veto threat, though, they began to make concessions to the governor’s position. For instance, the House’s map made Lawson’s district much more compact by centering it solely on Jacksonville — but it still had a big enough Black population to keep it Democratic-leaning. So DeSantis still claimed it was a racial gerrymander and vetoed it.

To many of the governor’s critics, this was evidence that DeSantis’s real goal was not an acceptable congressional map, but to burnish his image as a partisan warrior ahead of his possible 2024 presidential run. His refusal to concede districts to the opposing party will surely appeal to Republican primary voters who increasingly view Democratic power as unacceptable. And to a GOP base that cheers former President Donald Trump’s crusades against “RINOs” (Republicans in name only), DeSantis can offer the compelling argument that he stood up to members of his own party who were insufficiently cutthroat.

That argument is even stronger now. After months of staring DeSantis down, last week legislative leaders finally blinked, saying they would not propose any more maps and would vote on whatever proposal DeSantis submitted to them. It was a total political victory for the governor: Not only did he defeat the Legislature in their battle of wills, but he also didn’t have to concede a single Republican district.

However, DeSantis’s political victory doesn’t necessarily mean his map will be used in the 2022 election. With Democrats virtually guaranteed to sue over the plan, a court will ultimately decide its fate. And there are a lot of reasons to think the map is illegal under Florida law.

Most obviously, Republican legislators were correct when they argued that the Fair Districts amendment requires the preservation of a predominantly Black district in North Florida. Even DeSantis’s top lawyer has acknowledged that the Fair Districts amendment prohibits significantly decreasing the nonwhite population of a predominantly nonwhite district (in legal parlance, this is known as “retrogression”). But DeSantis’s map does just that. Under the current boundaries, the voting-age population of Lawson’s district is 44 percent Black and 40 percent white. Under the DeSantis map, it is 55 percent white and 30 percent Black.2

North Florida isn’t even the only place where DeSantis’s map short-changes Black voters. The map also splits Orlando’s Black community between the 10th and 11th districts. It’s debatable whether the current 10th District (represented by Democratic Rep. Val Demings) is protected under the Fair Districts amendment, but its new configuration under the DeSantis plan may not elect Black voters’ candidate of choice. According to local Democratic consultant Matthew Isbell, whites are now a plurality of the electorate in the Democratic primary there.

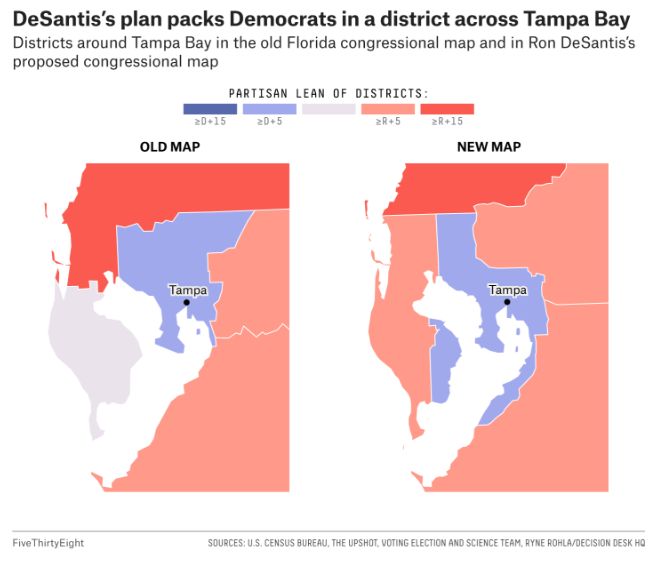

Then, of course, there’s the map’s extreme Republican bias, which is also at odds with the Fair Districts amendment. (“No apportionment plan or individual district shall be drawn with the intent to favor or disfavor a political party,” the amendment reads.) Perhaps the clearest example of the lines being drawn with partisan intent is in the Tampa Bay region, where there are currently two Democratic-held seats: the competitive 13th, on the western side of the bay, and the blue 14th, on the eastern side. DeSantis’s plan, however, would have the 14th District cross Tampa Bay to combine Democratic voters on the eastern and western sides into one district, thus moving the 13th from a highly competitive seat to a Republican-leaning one.

Despite voting for the plan this week, even some Republican legislators have privately told reporters that this configuration violates the Fair Districts amendment. How do they know? Because the Florida Supreme Court has said so in the past. In 2015, the court struck down Florida’s then-congressional map in part specifically because the 14th District crossed Tampa Bay.

There seems to be little question that Florida’s new congressional map is illegal under state law. So shouldn’t it be a slam dunk that the courts will throw it out? Not necessarily. The courts may agree with DeSantis’s position that the requirements of the Florida Constitution — specifically, its protections of minority districts — are themselves unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. Indeed, DeSantis’s implicit goal is to get the Fair Districts amendment struck down entirely — and this map is his vehicle for doing so.

It’s uncertain what the Florida Supreme Court will do here. On one hand, the court had no issues enforcing the Fair Districts amendment just seven years ago. On the other, four of the five justices who supported that ruling are now off the court — three of them replaced by DeSantis appointees. But then again, earlier this year, the court rejected DeSantis’s request for a preemptive, advisory opinion into whether Lawson’s district was legal, an action that was interpreted as a setback for the governor.

If the map is struck down, it would obviously be a blow to Republicans — and, presumably, DeSantis by extension. His refusal to budge from his hardline position may, in the end, result in a much better map for Democrats than the one he vetoed from the Legislature. But from a narrative perspective, DeSantis will probably be fine: He can still tell 2024 primary voters that he fought the good fight and blame the end result on other, less uncompromising Republicans.

But if the court upholds the map, it would be a much more tangible blow to Democrats and Black voters in Florida, who would find themselves with significantly less representation in Congress. And if the court strikes down the Fair Districts amendment in doing so, it would leave those people with no obvious legal recourse. In short, a lot is on the line in Tallahassee right now.

Nathaniel Rakich is a senior elections analyst at FiveThirtyEight. @baseballot

FiveThirtyEight

Mission

We use data and evidence to advance public knowledge — adding certainty where we can and uncertainty where we must.

Values

The values we aspire to in our journalism …

- Empiricism — We base our stories on evidence. We use many different kinds of evidence — data, reporting, first-hand experience, academic research, etc — but we also interrogate it for underlying biases.

- Accuracy and completeness — Our primary standard is: “Is this accurate and does it present as complete a picture as possible?” and not some impossible “objectivity” or ideological centrism. We’re rigorous, and make every effort to test our hypotheses and assumptions. When the truth runs contrary to prevailing narratives we aren’t afraid to push back.

- Transparency — We show — and share — our work. That means we explain how we reached our conclusions, and whenever possible, share the data behind our stories. It also means we acknowledge that we bring our own biases and perspectives to the work. The data does not speak for itself; we’re doing the speaking, and that requires us to think and work through how our own perspectives might influence our journalism and try to account for them.

- Inclusivity — We make work that is relevant and accessible to a diverse audience. We make journalism for and about people of all identities — by race, gender, age, ability and background. We make journalism for readers, not for other journalists. And we make journalism for everyone, not just experts.

- Humility — Our understanding of the world is iterative. We aren’t afraid to say, “we don’t know,” or that our old analysis is now outdated, and with new evidence our argument has changed. When we’re wrong, we say we were wrong.

- Personality — Our journalists can bring their whole selves to their work. We share who we are and let the personalities of our journalists shine through.