Will Amazon Workers’ Win Infect Walmart Next?

The improbable April 1 victory of Amazon workers in Staten Island, who fought for over two years to establish the very first union at the retail behemoth, is inspiring other Amazon employees around the country and highlighting a new path forward for the labor movement. It may also reignite labor organizing at Walmart, where workers seeking to form unions have been thwarted for decades.

More than two years after Amazon employee Christian Smalls led a small walkout at JFK8, the company’s sprawling distribution center on Staten Island, to protest its lack of COVID-19 health safety guidelines — soon after which he was fired — he returned in triumph. Earlier this month, at a joyful press conference on a grassy lot near the facility, Smalls and fellow organizers celebrated the historic Amazon Labor Union (ALU) win. The new union’s current focus is organizing LDJ5, the adjacent Amazon facility where elections began on April 25, with the potential of adding a second chapter to the ALU.

In addition, Amazon workers at a warehouse in New Jersey have reportedly gotten enough signatures to hold a union election. Smalls claims Amazon’s pricey union avoidance consultants have been deployed inside LDJ5, working aggressively to discredit organizers. Last year, the company spent $4.3 million on such consultants to defeat organizing efforts at its warehouses and facilities.

The headline-making union victory seemed to ride on a tide of momentum since Smalls led his first protest, with the pandemic revealing corporate greed and miserable working conditions, giving more clout to workers, and motivating employees across the country from Starbucks baristas to registered nurses fighting for the right to collectively bargain and form unions. Longtime labor organizer Peter Olney, the retired organizing director of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), calls this an “effervescent political moment,” one that he believes extends back to the election of Donald Trump and that includes seismic events like the Black Lives Matter protests and Bernie Sanders’ two presidential runs.

“The Sanders campaign dramatized social inequities in this country between the rich and the poor, while spawning a new generation of young people with left wing politics committed to labor,” he says. “Many of those folks went to work at Amazon where they’re active organizers.” COVID-19 laid bare Amazon’s ruthlessness, too, its lack of concern and care for its workers. “Amazon’s business model is one of churning employees,” says Olney. “It’s vicious, and the pandemic heightened people’s awareness of that. Not only workers, but consumers.

Another likely factor in the union’s success, compared to the as-yet unsuccessful effort by Amazon employees in Bessemer, Alabama — where the results of a do-over election hang on several hundred contested ballots — is that New York is a union-friendly state, with a 22% union membership rate, the second highest in the country behind Hawaii.

Nationally, public support for unions is at 68% — higher than at any other point since 1965. In addition to collective bargaining, workplace safety and greater job security, unions lead to higher wages. The median weekly earnings of nonunion workers are just 83% of those of unionized workers, according to data released in January by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. With union membership down slightly last year — 10.3% from 10.8% in 2020 — labor experts say unions must take advantage of current pro-union sentiment to actively boost their ranks.

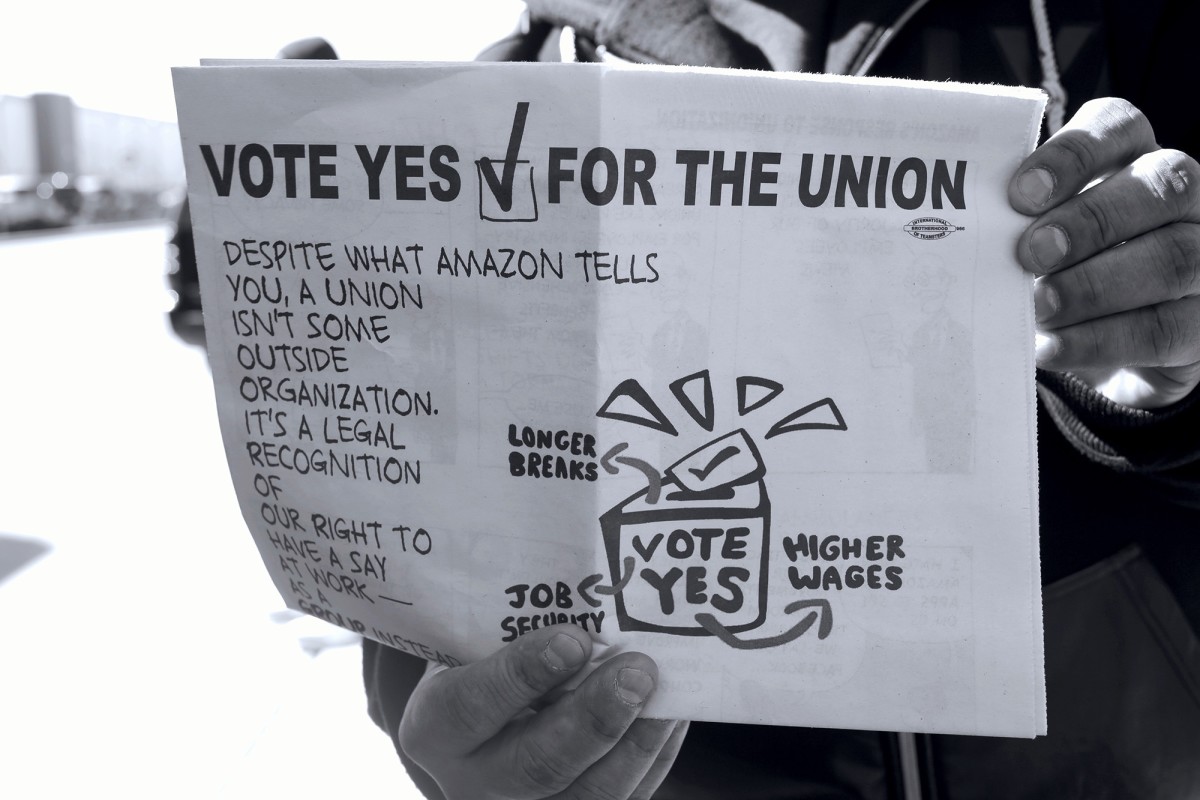

An attendee of the April 8 press conference displays union literature. Coco McPherson - Capital & Main

Chris Smalls and the ALU’s victory against such a powerful company raised inevitable comparisons with an earlier David and Goliath struggle — the blocked efforts by Walmart workers to organize unions in the 2000s.

Walmart — the world’s largest company by revenue, operating 10,600 stores and clubs in 24 countries and employing more than a million and a half Americans — has been virulently anti-union since its founding in 1962; critics say it has engaged in unfair labor practices, including worker intimidation and retaliation, for decades.

The company has also shuttered its own businesses to prevent workers from successfully organizing. When employees at a Walmart in Quebec voted to unionize in 2004, then attempted to negotiate the first Walmart contract in North America, the company closed the store rather than allow a union to gain a foothold.

In 2000, after meat cutters in Texas voted to join the United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW), Walmart eliminated the meat departments in that supermarket and nearly two hundred others across multiple states. Its labor practices have regularly drawn the attention of the National Labor Relations Board, the federal agency tasked with protecting the rights of private sector workers to join a union or to work collectively without one.

That didn’t stop workers from organizing for better conditions. Throughout the early-to-mid 2000s, worker-led groups around the country — including OUR (Organization United for Respect) Walmart, which was founded by workers from Laurel, Maryland, in 2011 and later financially supported by the UFCW — mobilized Walmart employees for sit-ins, strikes and walkouts on Black Friday, the busiest shopping day, actions designed to win concessions from Walmart and expand workers’ voices within the company. Successful campaigns have included Respect the Bump, which won maternity leave and pregnancy accommodations for workers.

Veterans of that campaign are adamant about their cause. “We believe that any worker should have the freedom and the right to stand up and organize whether it’s for a union, or for other forms of power, without retaliation,” says Andrea Dehlendorf, executive director of United for Respect, formerly OUR Walmart.

ALU members at the April 8 press conference. Coco McPherson - Capital & Main

Conditions in Walmart facilities would seem to make them ripe for union drives in 2022. According to data from the Economic Policy Institute, 83% of hourly Walmart employees earn less than $18 an hour, and more than half earn below $15 an hour. A 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that full-time Walmart workers across multiple states were paid such low wages that they qualified for Medicaid and food stamps.

Historically, formal union organizing has taken many different forms and employed different strategies. What worked for the Amazon Labor Union — a worker-run, nonhierarchical campaign in which all workers inside JK8 were encouraged to organize and reach out to other colleagues, and which was not associated with any larger established union — may or may not work for workers trying to unionize other companies.

Dehlendlorf calls what happened in Staten Island incredible. “It shows outside of the context of union-run electioning what’s possible within the current [National Labor Relations Board] structure. We need multiple models happening, but they need to be interconnected because we’ve never seen corporations of the scope and the scale of Amazon — and Walmart. You have to be in communication and dialogue with each other to be able to shift the way these corporations act and behave. Both to workers and in our society.”

In some ways, the ALU’s efforts harken back to an earlier era before the mid-20th century, when giant labor unions dominated manufacturing, says progressive journalist John Nichols, who has covered American politics, labor and unions for decades. He says that the ALU’s nimble, organic organizing strategies sparked by outrage over Amazon’s pandemic response echo those of the unions that formed in the 1930s. Many of those unions were independent, organic, rooted to particular places and communities.

“You can’t delink the story of the union victory on Staten Island with what happened before,” Nichols says. “And that is that Chris Smalls was fired in 2020 because he said, ‘This place isn’t safe.’ If you go back through labor history, this is a classic story. Somebody stood up for the workers and got fired for it. Workers see that and it has resonance. They understand that they were being treated unfairly, that they were asked to sacrifice where CEOs and investors — who reaped incredible profits — were not.”

Nichols calls this a COVID-influenced organizing effort. “And wouldn’t we assume that there are going to be openings for COVID-influenced organizing at Walmart? Let’s learn that lesson.”

Attendees of the ALU press conference carry signs supporting Amazon workers. Coco McPherson - Capital & Main

In the days following the ALU victory, President Biden, a longtime labor ally, expressed overwhelming support for the ALU, unions in general and the right of workers to organize in an address to the legislative conference of North America’s Building Trades Unions, citing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, a signature piece of pro-worker legislation currently stalled in the Senate. The PRO Act expands labor rights and further penalizes companies that violate the legal rights of workers to organize.

“We need to remove barriers to organizing — very relevant for Walmart — and we need some structures there so that when organizing has succeeded, the company can’t use its immense economic advantages to prevent a contract from being negotiated and implemented,” says Nichols.

Voting at LDJ5 began this week. On Sunday, high-profile supporters including Sen. Bernie Sanders, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, stood outside the facility and exhorted a fired-up crowd of union members representing hundreds of thousands of American workers to keep organizing. Evangeline Byars, a train operator and member of New York’s Transport Workers Union Local 100, also took the mic. “We stand in solidarity with you. This is the resurgence of the labor movement. The Amazon Labor Union winning their first building, it reset everything. Starbucks is next. Home Depot is next. Target is next. Walmart is next.”

In addition to this second election, the nascent ALU faces contract negotiations at JFK8. It’s a thorny process, though management is supposed to negotiate in good faith. In a press release in which it expressed disappointment over the successful union vote earlier in the month, Amazon hinted that it may file objections with the NLRB over what it called the agency’s “undue influence” during the election.

Chris Smalls remains undeterred. He wants all American workers to have access to the organizing strategies that resulted in his union’s historic win. Over 100 workers from Amazon facilities around the country — and in Japan — have reached out to the ALU for help in organizing their own workplaces. Derrick Palmer, the ALU’s vice president of organizing, says Walmart workers have called, too. Asked if he would consider helping non-Amazon workers, including Walmart workers, trying to unionize, Smalls said, “We could rename the union WALU, why not?”

This article was originally published on Capital & Main.

Coco McPherson (she/her) is a reporter and photographer with bylines in Capital & Main, Gothamist, Fast Company, Five Journal, Rolling Stone, Vibe, and The Village Voice, where she was also a weekly columnist. A 2019 Claremont Documentary Project Fellow, her photographs have been exhibited at Photoville 2021 in San Francisco, at the Bronx Documentary Center, and at metropolitan galleries including Urban Studio Unbound and PC4.McPherson's ongoing reporting projects examine environmental justice and political agency in New York's coastal communities.