When More is Not Better

Expert: NSA Phone-Tracking 'Insane'

Mass Surveillance in America: A Timeline of Loosening Laws and Practices

Repressing "Un-American Activities": The Historical Roots of Today's Homeland Surveillance State

Expert: NSA Phone-Tracking 'Insane'

By PHILIP EWING

Politico

June 6, 2013

http://www.politico.com/story/2013/06/james-bamford-nsa-phone-tracking-92379.html

A longtime expert on the National Security Agency calls its practice of vacuuming up millions of American phone records nothing short of “insane.”

James Bamford, who has written four books on the NSA and writes often about its practices since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, told POLITICO in an exclusive interview on Thursday the agency’s phone-tracking system was the latest case in which he said it overstepped the law under the pretext of defending the U.S. from its enemies.

NSA’s stock in trade has always been to try to accumulate ever-more data, Bamford said, up to the point that, as revealed by Wednesday’ report in the Britain’s Guardian newspaper, it tracks information about nearly every phone call made within the U.S. or from the U.S. to another country. Included are phone numbers, durations and locations of calls and other “metadata,” though not the content of the calls themselves.

“I’m sure they’re probably arguing that by having this data, they can prevent terror attacks by finding the Boston bomber-type people before these events take place, but there’s never been any evidence they’ve been able to do that,” Bamford said.

“The problem with that logic is, if you keep missing all these things they’ve missed – They missed the first World Trade Center bombing, the [attack on the destroyer USS] Cole, the East Africa embassies. They missed 9/11. They missed the underwear bomber. They missed Times Square [bombing attempt]. They missed the Boston bombers — if you have a problem with not finding these people, then maybe instead of building the haystack bigger, you should think about hiring more people good at finding needles in haystacks.”

But to continue Bamford’s metaphor, NSA is building one of the biggest haystacks in the world: A massive, $2 billion data center outside Salt Lake City that had a secret ribbon-cutting last week and is expected to begin operations this fall. Agency officials are said to want to use the new data center to store electronic information measured in quantities of “zettabytes,” including, observers think, the kinds of call records that Wednesday’s report shows the NSA gets from Verizon.

The phone records, Bamford said, “are a perfect example of what they’re using it for. It’s the cloud, it’s the storage for NSA’s worldwide eavesdropping, so if they’re eavesdropping on communications in Libya, or China, or Afghanistan someplace, it all gets transferred back to one single location, in Bluffdale … that’s where they would put all these data they’re talking about they’re getting from the metadata – it’s all digits being transferred over wires in hardware.”

A senior government official defended the NSA’s practices on Thursday, arguing that its data collection “has been a critical tool in protecting the nation from terrorist threats to the United States, as it allows counterterrorism personnel to discover whether known or suspected terrorists have been in contact with other persons who may be engaged in terrorist activities, particularly people located inside the United States.”

House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Rogers (R-Mich.) went even further on Thursday, declaring to reporters that the NSA’s phone-tracking “was used to stop a terrorist attack in the United States.”

“We know that,” he said. “It’s important. It fills in a little seam that we have. And it’s used to make sure that there’s not an international nexus to any terrorism event that they may believe is ongoing in the United States.”

Bamford, however, said Wednesday’s Guardian report described “an expansion of power that’s never happened before – the use of NSA for domestic surveillance on virtually all of the Americans in the U.S.” He compared it to the practices of the government of East Germany, where, as Bamford put it, “everybody’s a suspect until you prove you’re not a suspect.”

Mass Surveillance in America: A Timeline of Loosening Laws and Practices

by Cora Currier, Justin Elliott and Theodoric Meyer

ProPublica

June. 7, 2013

http://projects.propublica.org/graphics/surveillance-timeline

On Wednesday, the Guardian published a secret court order requiring Verizon to hand over data for all the calls made on its network on an “ongoing, daily basis.” Other revelations about surveillance of phone and digital communications have followed.

That the National Security Agency has engaged in such activity isn’t entirely new: Since 9/11, we've learned about large-scale surveillance by the spy agency from a patchwork of official statements, classified documents, and anonymously sourced news stories.

1978

Surveillance court created

Sen. Frank Church (D-Idaho) led the investigation.

Sen. Frank Church (D-Idaho) led the investigation.After a post-Watergate Senate investigation documented abuses of government surveillance, Congress passes the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA, to regulate how the government can monitor suspected spies or terrorists in the U.S. The law establishes a secret court that issues warrants for electronic surveillance or physical searches of a “foreign power” or “agents of a foreign power” (broadly defined in the law). The government doesn’t have to demonstrate probable cause of a crime, just that the “purpose of the surveillance is to obtain foreign intelligence information.”

The court’s sessions and opinions are classified. The only information we have is a yearly report to the Senate documenting the number of “applications” made by the government. Since 1978, the court has approved thousands of applications – and rejected just 11.

Oct. 2001

Patriot Act passed

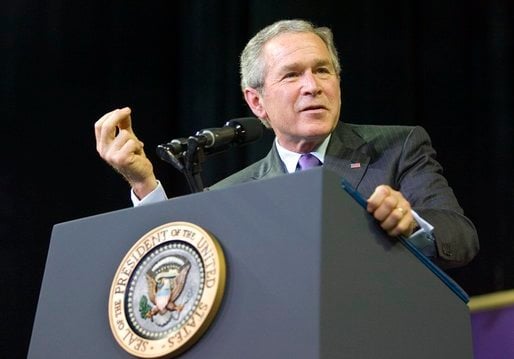

President George W. Bush signs the Patriot Act.

President George W. Bush signs the Patriot Act.In the wake of 9/11, Congress passes the sweeping USA Patriot Act. One provision, section 215, allows the FBI to ask the FISA court to compel the sharing of books, business documents, tax records, library check-out lists – actually, “any tangible thing” – as part of a foreign intelligence or international terrorism investigation. The required material can include purely domestic records.

Oct. 2003

‘Vacuum-cleaner surveillance’ of the Internet

Mark Klein

Mark KleinAT&T technician Mark Klein discovers what he believes to be newly installed NSA data-mining equipment in a “secret room” at a company facility in San Francisco. Klein, who several years later goes public with his story to support a lawsuit against the company, believes the equipment enables “vacuum-cleaner surveillance of all the data crossing the Internet – whether that be peoples' e-mail, web surfing or any other data.”

March 2004

Ashcroft hospital showdown

Attorney General John Ashcroft

Attorney General John AshcroftIn what would become one of the most famous moments of the Bush Administration, presidential aides Andrew Card and Alberto Gonzales show up at the hospital bed of John Ashcroft. Their purpose? To convince the seriously ill attorney general to sign off on the extension of a secret domestic spying program. Ashcroft refuses, believing the warrantless program to be illegal.

The hospital showdown was first reported by the New York Times, but two years later Newsweek provided more detail, describing a program that sounds similar to the one the Guardian revealed this week. The NSA, Newsweek reported citing anonymous sources, collected without court approval vast quantities of phone and email metadata "with cooperation from some of the country’s largest telecommunications companies" from "tens of millions of average Americans." The magazine says the program itself began in September 2001 and was shut down in March 2004 after the hospital incident. But Newsweek also raises the possibility that Bush may have found new justification to continue some of the activity.

Dec. 2005

Warrantless wiretapping revealed

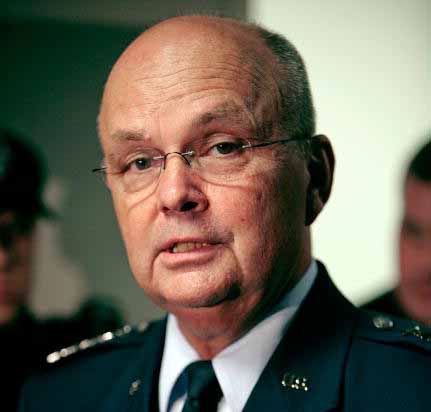

Michael Hayden, director of the NSA when the warrantless wiretapping began

Michael Hayden, director of the NSA when the warrantless wiretapping beganThe Times, over the objections of the Bush Administration, reveals that since 2002 the government “monitored the international telephone calls and international e-mail messages of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people inside the United States without warrants.” The program involves actually listening in on phone calls and reading emails without seeking permission from the FISA Court.

Jan. 2006

Bush defends wiretapping

President Bush speaks at Kansas State University.

President Bush speaks at Kansas State University.President Bush defends what he calls the “terrorist surveillance program” in a speech in Kansas. He says the program only looks at calls in which one end of the communication is overseas.

March 2006

Patriot Act renewed

The Senate and House pass legislation to renew the USA Patriot Act with broad bipartisan support and President Bush signs it into law. It includes a few new protections for records required to be produced under the controversial section 215.

May 2006

Mass collection of call data revealed

USA Today reports that the NSA has been collecting data since 2001 on phone records of “tens of millions of Americans” through three major phone companies, Verizon, AT&T, and BellSouth (though the companies level of involvement is later disputed.) The data collected does not include content of calls but rather data like phone numbers for analyzing communication patterns.

As with the wiretapping program revealed by the Times, the NSA data collection occurs without warrants, according to USA Today. Unlike the wiretapping program, the NSA data collection was not limited to international communications.

2006

Court authorizes collection of call data

The mass data collection reported by the Guardian this week apparently was first authorized by the FISA court in 2006, though exactly when is not clear. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., chairwoman of the Senate intelligence committee, said Thursday, “As far as I know, this is the exact three-month renewal of what has been in place for the past seven years.” Similarly, the Washington Post quoted an anonymous “expert in this aspect of the law” who said the document published by the Guardian appears to be a “routine renewal” of an order first issued in 2006.

It’s not clear whether these orders represent court approval of the previously warrantless data collection that USA Today described.

Jan. 2007

Bush admin says surveillance now operating with court approval

Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez

Attorney General Alberto GonzalezAttorney General Alberto Gonzales announces that the FISA court has allowed the government to target international communications that start or end in the U.S., as long as one person is “a member or agent of al Qaeda or an associated terrorist organization.” Gonzalez says the government is ending the “terrorist surveillance program,” and bringing such cases under FISA approval.

Aug. 2007

Congress expands surveillance powers

The FISA court reportedly changes its stance and puts more limits on the Bush administration’s surveillance (the details of the court’s move are still not known.) In response, Congress quickly passes, and President Bush signs, a stopgap law, the Protect America Act.

In many cases, the government can now get blanket surveillance warrants without naming specific individuals as targets. To do that, the government needs to show that they’re not intentionally targeting people in the U.S., even if domestic communications are swept up in the process.

Sept. 2007

Prism begins

The FBI and the NSA get access to user data from Microsoft under a top-secret program known as Prism, according to an NSA PowerPoint briefing published by the Washington Post and the Guardian this week. In subsequent years, the government reportedly gets data from eight other companies including Apple and Google. “The extent and nature of the data collected from each company varies,” according to the Guardian.

July 2008

Congress renews broader surveillance powers

Congress follows up the Protect America Act with another law, the FISA Amendments Act, extending the government’s expanded spying powers for another four years. The law now approaches the kind of warrantless wiretapping that occurred earlier in Bush administration. Senator Obama votes for the act.

The act also gives immunity to telecom companies for their participation in warrantless wiretapping.

April 2009

NSA ‘overcollects’

The New York Times reports that for several months, the NSA had gotten ahold of domestic communications it wasn’t supposed to. The Times says it was likely the result of “technical problems in the NSA’s ability” to distinguish between domestic and overseas communications. The Justice Department says the problems have been resolved.

Feb. 2010

Controversial Patriot Act provision extended

President Obama

President ObamaPresident Obama signs a temporary one-year extension of elements of the Patriot Act that were set to expire -- including Section 215, which grants the government broad powers to seize records.

May 2011

Patriot Act renewed, again

The House and Senate pass legislation to extend the overall Patriot Act. President Obama, who is in Europe as the law is set to expire, directs the bill to be signed with an “autopen” machine in his stead. It’s the first time in history a U.S. president has done so.

March 2012

Senators warn cryptically of overreach

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.)

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.)In a letter to the attorney general, Sens. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Mark Udall, D-Colo., write, “We believe most Americans would be stunned to learn the details” of how the government has interpreted Section 215 of the Patriot Act. Because the program is classified, the senators offer no further details.

July 2012

Court finds unconstitutional surveillance

According to a declassified statement by Wyden, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court held on at least one occasion that information collection carried out by the government was unconstitutional. But the details of that episode, including when it happened, have never been revealed.

Dec. 2012

Broad powers again extended

President Obama

President ObamaCongress extends the FISA Amendments Act another five years, and Obama signs it into law. Sens. Wyden and Jeff Merkley, both Oregon Democrats, offer amendments requiring more disclosure about the law’s impact. The proposals fail.

April 2013

Verizon order issued

As the Guardian revealed this week, Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Judge Roger Vinson issues a secret court order directing Verizon Business Network Services to turn over “metadata” -- including the time, duration and location of phone calls, though not what was said on the calls -- to the NSA for all calls over the next three months. Verizon is ordered to deliver the records “on an ongoing daily basis.” The Wall Street Journal reports this week that AT&T and Sprint have similar arrangements.

The Verizon order cites Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which allows the FBI to request a court order that requires a business to turn over “any tangible things (including books, records, papers, documents, and other items)” relevant to an international spying or terrorism investigation. In 2012, the government asked for 212 such orders, and the court approved them all.

June 2013

Congress and White House respond

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper

Director of National Intelligence James ClapperFollowing the publication of the Guardian’s story about the Verizon order, Sens. Feinstein and Saxby Chambliss, R-Ga., the chair and vice of the Senate intelligence committee, hold a news conference to dismiss criticism of the order. “This is nothing particularly new,” Chambliss says. “This has been going on for seven years under the auspices of the FISA authority, and every member of the United States Senate has been advised of this.”

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper acknowledges the collection of phone metadata but says the information acquired is “subject to strict restrictions on handling” and that “only a very small fraction of the records are ever reviewed.” Clapper alsoissues a statement saying that the collection under the Prism program was justified under the FISA Amendments of 2008, and that it is not “intentionally targeting” any American or person in the U.S.

Statements from the tech companies reportedly taking part in the Prism program variously disavow knowledge of the program and merely state in broad terms they follow the law.

Repressing "Un-American Activities": The Historical Roots of Today's Homeland Surveillance State

By Greg Guma

Global Research

June 07, 2013

http://www.globalresearch.ca/repressing-un-american-activities-the-historical-roots-of-todays-homeland-surveillance-state/5338111

Political rights are so easily taken for granted – until they’re threatened or curtailed by repressive laws. In the United States, they are usually most vulnerable when people are anxious about some outside threat.

After World War II, for instance, dissent became risky as relations with Russia hardened into Cold War I. Hysteria about domestic Communist subversion led quickly to state and congressional investigations of “un-American activities.” And in 1951, a Supreme Court decision led to the imprisonment of eleven Communist leaders, not for any overt acts threatening national security, but rather for trying to organize a political party and teach Marxism.

Today the threats to political liberty are no less imminent.

The groundwork was actually laid when a proposal for a massive rewrite of the US criminal code became the Nixon administration’s blueprint for crushing dissent and savaging the Bill of Rights. After Watergate and FBI-CIA revelations, proposed charters for the intelligence community were exploited as springboards to legalize intrusive techniques. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court moved toward prior restraint of free speech.

Prior restraint of the press became government policy in March 1979 when The Progressive magazine was prevented from publishing an article on the H-bomb. The ban succeeded for six months, on grounds that the 1954 Atomic Energy Act gave the government the right to suppress nuclear knowledge. Although the case was eventually dropped, the law may very well be used again.

Support from other publications was slow in coming, possibly because the case involved a small Wisconsin monthly rather than a daily giant like The New York Times’ publication of the Pentagon Papers. The press gag ended only when other researchers found and printed the same “secrets.”

Even though the government dropped its case, it asserted that the section on violating national security secrets in the Atomic Energy Act would continue to be enforced, one of several “loaded pistols aimed at the First Amendment,” as writer Nat Hentoff put it.

In February 1980, the Supreme Court ruled, in the case of ex-CIA agent Frank Snepp, that government agencies have the right to restrict publication of national security information – even if the material is unclassified – when the book or article has been produced by a government worker with access to “confidential sources.”

The Court had effectively usurped the lawmaking powers of Congress and gone a long way toward enacting an American version of the British Official Secrets Act. In a letter to The New York Times, Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz, who was working with Ted Kennedy at the time, said that an Official Secrets Act might not be needed since “we have one now.”

The decision went further that penalizing one CIA employee for breaking his contract. Any government worker in a relationship of trust with his agency, whether or not a written agreement exists, could have rights to speech diminished. The high court, with four Nixon appointees in the majority, buttressed lower court decisions involving CIA censorship of ex-agent Victor Marchetti. That case dealt with classified material, and the Court set up a powerful precedent for prior restraint that violated the public’s right to know.

In the 1950s and afterward, the intelligence community saw itself in a war with those who supposedly threatened the existing social order. Programs conducted in the heat of the Cold War ranged from, multi-million dollar covert actions worldwide – secret support for pro-American political parties, destabilization of “unfriendly” regimes, arms transfers, training and propaganda – to a wide range of domestic “counter-intelligence” efforts.

Americans were shocked to learn that the FBI, CIA, National Security Agency (NSA) and others had conducted massive campaigns of spying and subversion directed at American citizens, most of whom had never committed any crimes.

After the revelations of the mid-1970s Congress moved toward defining a set of standards, to be codified in several laws. But by the time the first of these, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) was passed in 1978, the mood had already changed. There was little objection when CIA Director Stansfield Turner nullified regulations banning the use of journalists, academics and the clergy in intelligence work.

Under a 1978 Presidential order on intelligence work, an investigation or covert project could be initiated if a person was “reasonably believed” to be involved in activities which may or may not involve legal violations, or was aiding or conspiring in these possible activities. Reasonable belief as a standard does not require concrete evidence that a law is being broken. The “potential” for a threat can be enough.

As pressures for action in the Middle East mounted, President Carter asked for a freer rein in initiating programs (the CIA was already supplying arms to rebels in Afghanistan, according to several sources). Carter also wanted less public access to CIA information. One proposal was to bar US citizens from obtaining information about any program that didn’t directly involve the individual.

Critics of this exemption to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) said it would damage historical and journalistic research and informed public debate. Yet, in a hasty reaction to international tensions, congressional oversight and an independent check of intelligence operations became another casualty of the obsession with “national security.”