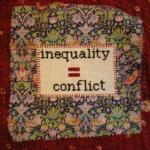

Inequality, Power and Class: Why Language Matters

The stories we tell ourselves as families and as a nation about the “haves and have nots” shape the opportunities and the struggles of millions of people. Yet in a country that still thinks “being classy” is a compliment, we lack an adequate language for talking about the realities of class and the experiences of class-based exploitation and discrimination.

In the US, discourses of inequality seldom are rooted to the nation’s long history of violent class conflict. Two examples of that history which come quickly to mind are the 1892 Homestead steel strike in Pittsburgh, which earned a place in labor history as the Homestead Massacre and the 1921 coal strike known as the Battle of Blair Mountain in which workers saw their homes bombed as they faced army troops. These were extreme but not unique moments in the history of labor. Oppressive working conditions and inadequate pay have never been an accident or the result of an oversight — they have been for profit.

Efforts to gain basic workplace protections, such as child labor laws and an eight-hour workday, were consistently met with violent repression from businesses and government. Despite these efforts, workers have yet to gain a right to a living wage. Today, class-based power struggles and the language that defined them too often are eclipsed in conversations about inequality. While labor has won important concessions, it is no exaggeration to say they lost the class struggle and with it the language of class. The limited success of labor organizers among farm workers and more recently among Amazon workers seem only to illustrate the loss.

A century after violent efforts to suppress resistance to class exploitation, the nation has learned to think about people and the economy with a language that favors the wealthy and elides issues of power. If workers lack class-based identities, the same cannot be said of the economic elite who consistently advance their own interests — as a class. The interests of the economic elite are apparent in the nation’s tax policies that protect wealth. They are also apparent in the government’s unrealistic definition of poverty ($27,750 for a family of four in 2022) which both undercounts the numbers of people who are struggling and limits eligibility for public support.

The interests of the economic elite are also apparent in a wholly inadequate federal minimum wage, frozen at $7.25 since 2009, and in glowing reports of increased jobs that fail to mention that these are largely service sector jobs that do not pay a living wage or basic benefits such as sick leave or health care. And, they are apparent in measures of national economic success rooted to GDP and corporate profit rather than to the economic self-sufficiency and overall health of the nation’s workers.

GET THE FACTS

Income Inequality

At a time when much of the country identifies as being middle class regardless of income, the term “working class” is used as a euphemism for poor people, many of whom work in service sector jobs characterized by low pay, part-time hours, no benefits, and general instability. Just 50 years ago, “working class jobs” referred to skilled and physically demanding work. The blue-collar workers who held those jobs earned a middle-income wage that paid for a mortgage, a family car, often a boat or recreational vehicle, and sometimes a vacation home. Those jobs have largely been replaced by low-wage service sector employment.

During the pandemic, another euphemism emerged as business and media characterized some forms of work as “essential” to justify demands that people to continue to work in conditions that placed them at risk of Covid-19. If medical professionals could be called essential workers in a pandemic, the same cannot be said of millions of service workers who were required to work with inadequate protections, sick leave, or health care. The nation called low-wage workers essential yet treated them as disposable.

In the 21st century, our use of language has effectively scrambled class-based identities among workers even as 35% of households have so little economic security, they are unable to pay for an unexpected expense of $400. The erasure of workers’ interests is normalized in large and small ways. Consider that every major metropolitan newspaper in the country has a business section, yet none has a workers’ section. For decades the needs, interests, and perspectives of workers have been treated by newspapers either as irrelevant or as commensurate with those of business. It is both a mundane and a striking omission of class-based interests.

Systemic class exploitation is masked by the discourse of the American Dream which advances the myth that everyone has a chance to succeed if only they work hard enough. Class prejudice runs rampant when structural inequalities are reduced to personal characteristics. In short, struggling workers and the families they support are blamed for being poor, no matter how hard or how long they labor. If being stuck in a lifetime of low-wage work was the consequence of personal deficiencies, rather than structural design, we wouldn’t have millions of families in the same sinking boat.

In 2022, it is still acceptable for successful businesses to refuse to pay a living wage to their workers. If we are to turn things around, the nation needs sustained and honest public conversations, actions, and policies that address the realities of economic exploitation on which business success too often depends. It begins with creating a language that captures the experience of class-based violence as it exists today.